(East Arcadia, North Carolina, October 22, 1895 – Oyster Bay, New York, July 18, 1977).1

Oxford ✯ Flight training in England ✯ France and No. 11 Squadron R.A.F. ✯ September 16, 1918, and after ✯

Earlier generations of Julian Carr Stanley’s family used the last name Stanaland; his grandfather is recorded as both John C. [Collier] Stanaland and John C. Stanley in a North Carolina land grant document from 1853.2 It appears that a Hugh Stanaland emigrated to New Jersey from England in the mid-seventeenth century and that a grandson, also Hugh, came to Craven County, North Carolina, in the early eighteenth century. Descendants settled in various counties in the southeastern part of North Carolina.3

Julian Carr Stanley’s father, John Calvin Stanley, was associated with Marlville (also called East Arcadia) in Bladen County and was appointed postmaster there in 1885.4 Four years previously he had married Lucy L. Chauncy.5 The couple had four children. Julian Carr Stanley, the youngest, was particularly close to the oldest child and only daughter, Lois R. Stanley. According to an account by Julian Carr Stanley’s son, a fire destroyed the family home in East Arcadia.6 Father and children relocated to Jacksonville, Florida,7 but the mother, who became ill in the aftermath of the fire, remained in Wilmington, North Carolina, and died there in July of 1905.8 John Calvin Stanley remarried and had two more children. This was evidently an unsettled time for Julian Carr Stanley; he was sent to military school but ran away.9 He is recorded as having attended Deland High School and Duval High School.10

John Calvin Stanley died in early 1911, and Julian Carr Stanley became the ward of Charles L. Bagwell, husband of his sister Lois.11 On the recommendation and with the help of Charles Buxton Rogers, with whose son, Alonzo, he had been in school, Stanley successfully applied to The Lawrenceville School, a private preparatory school in Lawrenceville, New Jersey, which he attended from the autumn of 1912 through his graduation in June 1914. In the fall of that year he was appointed as an alternate to West Point12 and spent the next months in Jacksonville working at a timber firm and then in a bank. By the autumn of 1915 he had given up the idea of going to West Point and instead set his sights on Yale. He is sometimes recorded as in the Yale Sheffield Scientific School class of 1918, but also in the class of 1919.13 However, like many college men of his age who went to war, he left before completing his degree and finished up upon his return from Europe.

In the late autumn of his first term at Yale Stanley became a member of Battery A of the newly formed Yale Battalion (10th Militia Field Artillery, Organized Militia of Connecticut).14 The following spring he became one of twenty men from the Battalion who joined the Aero Corps of the Yale Battery.15 The men were to receive instruction on dirigibles and observation balloons at Hartford and New Haven.16 The Yale Battalion went on to train in Tobyhanna, Pennsylvania in the summer of 1916 where it was rumored that the Aero Corps would have the use of an airplane17; I have not been able to determine whether this actually happened.

Also uncertain is whether Stanley was posted to the Southwest in connection with the Mexican Border War. His R.A.F. service record records his having “Fair Spanish” (which he had studied at Lawrenceville) and having received the Mexican Border Medal.18 However, when Stanley filled out the Connecticut Military Census form in 1917, he only recorded having served in Tobyhanna, and, while some Connecticut Militia did go to El Paso in July 1916, Connecticut artillery troops were not among them.19

The Yale Battalion was mustered out at the end of the year. The men were reorganized into a Reserve Officers Training Corps, and it was expected that they would train at Fort Sill in Oklahoma.20 Stanley, however, was evidently determined to continue in aviation. His draft card indicates that in April 1917 he was stationed at Bay Shore on Long Island and serving in the aviation section of the Naval Militia of New York; again I have not been able to determine whether he gained any actual flying experience there.21 By this time his sister and her husband had moved to El Paso, which presumably accounts for Stanley’s having registered for the draft, by mail, in El Paso.22 His son records that “On 20 June 1917 he was granted a discharge from the Naval militia and National Naval Volunteers.”23 Stanley was accepted by the Aviation Section of the Signal Corps and attended the School of Military Aeronautics at the University of Illinois at Champaign, in the same class as John McGavock Grider, graduating August 25, 1917.24

Government flight training facilities in the U.S. existed at this time mostly on paper, and offers from the Allies to train American pilots were welcomed. Around the time that Stanley’s ground school class graduated, there were openings in Foggia, Italy, and about one third of the men in this class, including Stanley, chose or were chosen to go to Italy for flight training. They were thus among the 150 men of the “Italian detachment” who travelled to Europe on the Carmania with the expectation that they would train in Italy. The ship departed New York on September 18, 1917, and, after a stopover at Halifax to meet up with a convoy, set out for the Atlantic crossing.

The men of the detachment travelled first class and had a good deal of leisure, apart from Italian lessons conducted by Fiorello La Guardia, assisted by violinist Albert Spalding. The entry for September 29, 1917, in War Birds mentions Stanley, using the nickname he consistently went by. “We had a big crap game later in our staterooms. First Jake Stanley took all the money and then [Elliott White] Springs took it all from him and finally [James Whitworth] Stokes ended up with it all.” This passage is perhaps based on the entry for September 22, 1917, in Grider’s original diary, where there is a mention of cards, although the players are not named.25 Towards the end of the voyage, as the convoy entered particularly dangerous waters, the men were assigned to submarine watch duty which was, fortunately, uneventful.

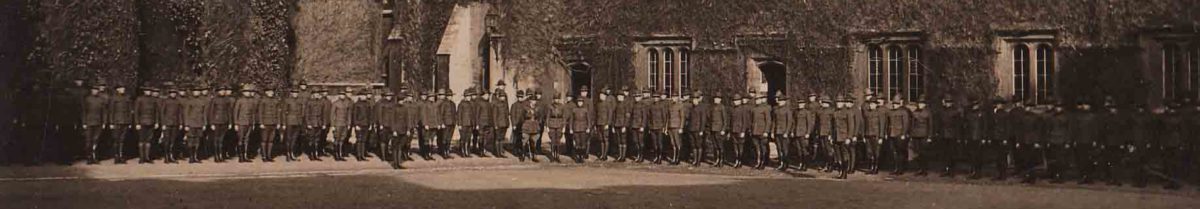

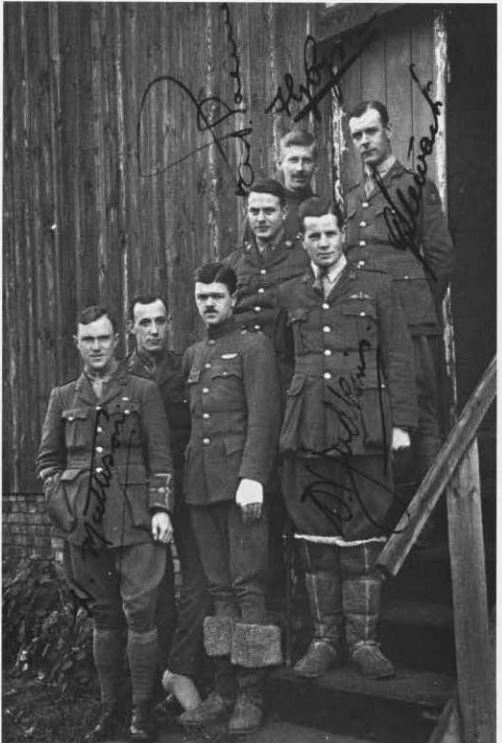

When the Carmania docked at Liverpool on October 2, 1917, there was a change of plans. The men were not to go on to Italy but to remain in England and, even worse, as it seemed, to go through ground school all over again. They travelled by rail to Oxford and Oxford University where the Royal Flying Corps’s No. 2 School of Military Aeronautics was located. The “Italian detachment” became the “second Oxford detachment”—a first detachment of fifty American pilots in training having arrived there a month earlier. At Oxford the men spent their first night scattered among the various colleges; it appears from a passing remark in the diary of Paul Stuart Winslow of the first Oxford detachment that Stanley, along with Laurence Kingsley Callahan, had been assigned to Exeter.26 The next day the 150 men were divided into two groups, and sixty were assigned to The Queen’s College, while the remainder, including Stanley, were housed in Christ Church College with Springs in charge of them. During their time at Christ Church, a photo was taken of the American and British cadets at the college, and Stanley can be identified in the second row from the bottom, ninth from the right.

There was initially grumbling at having to repeat ground school, but the British instructors, unlike the ones in U.S., had had war flying experience, and this added some interest to the courses, which otherwise covered material familiar from U.S. ground schools (which were modeled on the R.F.C.’s). As Callahan recalled, “We didn’t have any work to do because we already knew everything.”27 He also said that “we never had more fun in our life than we did at Oxford.”28

Particularly memorable among the fun times at Oxford was the evening of Saturday, October 20, 1917, when members of the first Oxford detachment celebrated finishing their exams and graduating from their R.F.C. ground school course, and also when Stanley celebrated his birthday (two days early apparently, but the 22nd would have been a Monday, when men would have had to stay in college in the evening). The venue was Boul’s, and much beer and champagne was consumed. When it came time for Stanley’s birthday cake, “he yelled at the top of his voice for attention and when everything was quiet said ‘now Genlmen I am about to tut this twake[’],” as Grider recalled in his diary; the account in War Birds tells how Stanley “kept announcing that he was going to ‘tut the twake.’”29

Later in the evening a couple of men got crosswise with the British authorities. In consequence all the Americans were ordered to move into the same college, Exeter, rather than remaining divided between Christ Church and Queen’s. Stanley was assigned a large room on the ground floor with Joseph Kirkbride Milnor, Dudley Hersey Mudge, and Joseph Frederick Stillman.30

The October 22, 1917, entry in War Birds with its account of Stanley’s birthday also mentions that “We had a boxing-tournament last week. Springs and I [Grider] went in and won our first bouts, but got knocked out in the second round. [Chester Arthur] Pudrith and Jake Stanley each won in their classes and got a trip to London over the week-end as prizes.” This is evidently poetic license on Springs’s part, as it would put Stanley in Oxford and London on the same weekend. Another detachment member, Parr Hooper, recalls the boxing tournament taking place the following week, and William Thomas Clements, also from the detachment, indicates that the tournament happened on Thursday and Friday, October 25 and 26, 1917.31 Neither Hooper nor Clements names the winners, but Clements does note that “As prizes, two were given week-end leave to London. . . .”32 Springs himself, in a letter home dated November 1, 1917, refers to a recent boxing tournament in which he, Springs, won a trip to London, with no reference to Stanley or Pudrith.33

It had been rumored that ground school at Oxford would last six weeks, and the men were relieved when they found it would be only four. Most of them, nevertheless, were in for a major disappointment, as they were sent at the beginning of November 1917 to a machine gunnery camp in Yorkshire; there simply were not enough places at R.F.C. training squadrons. Stanley, however, was among the fortunate men chosen by Springs to go to No. 1 Training Depot Station at Stamford where there were openings for twenty men to start flight training. At least according to War Birds, Springs “picked those who’d done the most flying already,” which would suggest that Stanley may have done some flying while still in the States.34 The twenty made the six-hour train journey from Oxford via Rugby to Stamford on November 5, 1917.35

It was some time before the men were able to fly. The day after they arrived, they spent the morning in classes. Hopes that they might begin instruction that afternoon were dashed when they arrived at the flying field to find that an instructor, with Springs as his passenger, had just crashed the new Curtiss JN-4.36 Springs records his first actual training flight on November 12, 1917; William Hamlin Neely, also at Stamford, seems to have flown for the first time on November 17, 1917.37 Stanley, meanwhile, had evidently fallen ill or been injured and thus perhaps did not fly at all in November. William Ludwig Deetjen, another of the men at Stamford, noted in his diary on December 6, 1917, that “Jake Stanley returned from the hospital where he has been over two weeks. The man who performed the operation was an optician before the war.” I have found no further information about this or about Stanley’s remaining time at Stamford, but he presumably, like the others, put in time on Curtis Jennys and Avros over the course of December and January. It is apparent from Neely’s and Springs’s log books as well as from Deetjen’s diary that the pace of instruction at 1 T.D.S. began to pick up after the slow start, although there was never as much flying as they wanted.

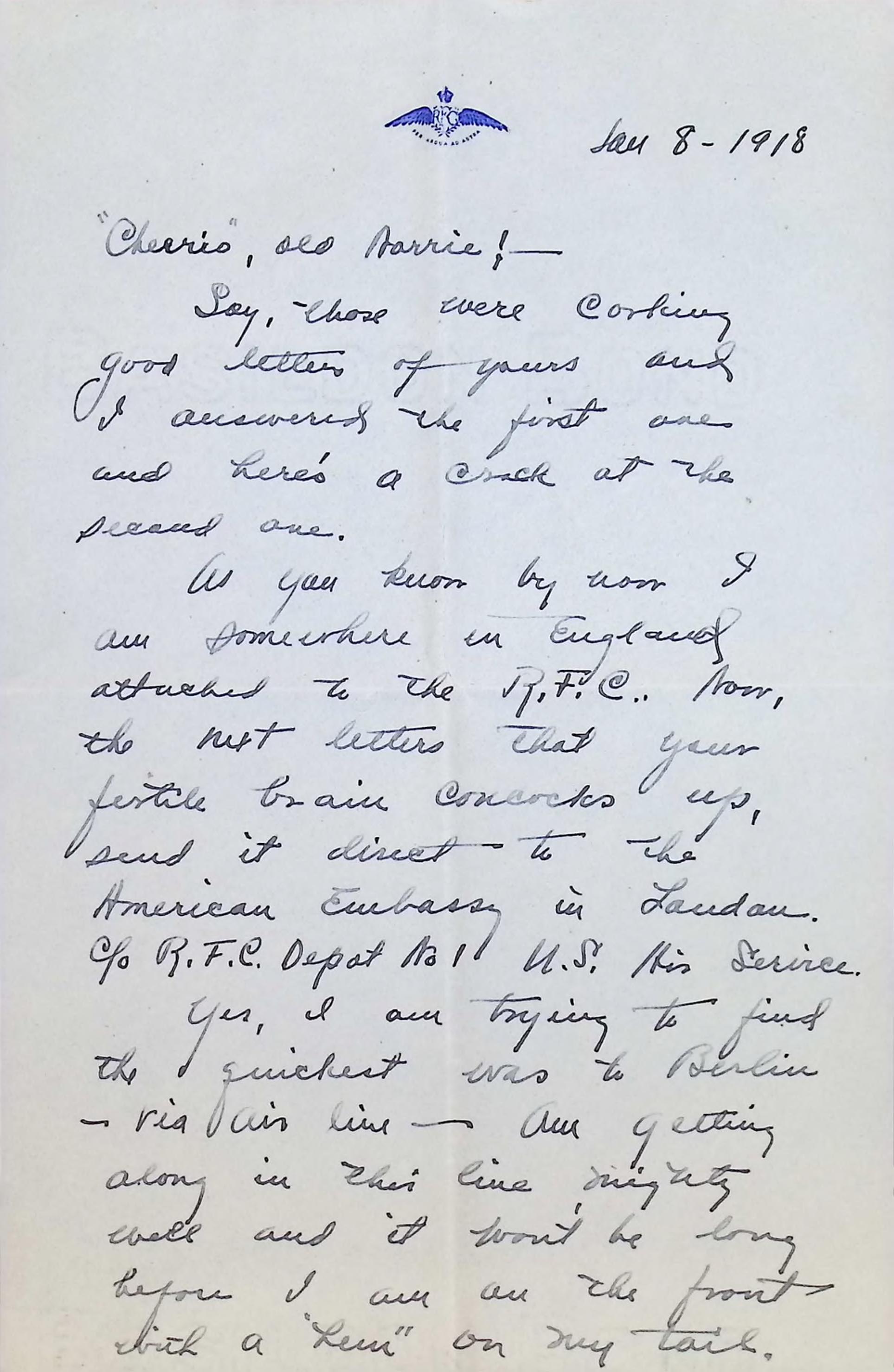

On January 8, 1918, Stanley wrote a short, cheerful letter to Percival Chadwick Norris, a teacher at The Lawrenceville School who had taken it on himself to keep track of Lawrenceville students in service and to write a monthly newsletter to them. In his letter, Stanley remarks that “[I] am doing work on scouts and fighters now. . . .”38 This is unlikely, given that he was at an elementary training squadron, but indicative of Stanley’s aspirations—many of the men wished to become fighter rather than bomber or observation plane pilots.

Despite having been in hospital for two weeks, Stanley was apparently able to graduate from elementary training at Stamford with others who had been assigned there with him. On January 16, 1918, he, Deetjen, Donald Elsworth Carlton, and Walter Chalaire left Stamford for No. 44 Training Squadron at Waddington, near Lincoln.39 This posting would have put Stanley on course to become a bombing or observation pilot; much of the training at Waddington aimed at turning out DH-4 and DH-9 pilots.

On February 11, 1918, John Warren Leach, stationed at No. 5 T.D.S. near Stamford, noted in his log book that he took “Jake Stanly” up as a passenger in a B.E.2e. It seems likely that Stanley was back at Stamford visiting rather than having been assigned there, for a postcard that he sent his Lawrenceville School teacher Norris on February 19, 1918, bears a Lincoln postmark. He writes of having had a forced landing out in the country: “Crashed machine— bruised body, but still alive. — Farmers house — plenty of gin!!”40

Sometime in the latter half of February Stanley had done enough flying, including solo flying, to be recommended for his commission—he was thus keeping up with, for example, his ground school friends Grider and Callahan, as well as Deetjen.41 Cablegram 979-R from Washington confirming the recommendation is dated March 25, 1918. There was another delay, and then on April 7, 1918, Stanley was placed on active duty.42 At this point he was at Stonehenge in Wiltshire, where the No. 1 School of Navigation and Bomb Dropping was located, and an entry in Deetjen’s diary indicates Stanley was still at Stonehenge on April 24, 1918.

It may be that Stanley, prior to his time at Stonehenge, was assigned to the No. 4 School of Aerial Gunnery at Marske-by-the-Sea in Yorkshire43 and that at Marske he, like Leach and Deetjen, flew a Bristol Fighter, a two-seater reconnaissance and fighter plane. Although Stanley’s advanced training was on two-seater bombing and observation planes, in particular DH-4s, he continued determined to be a scout (fighter) pilot. Flying a Bristol Fighter would have allowed him to combine training and aspiration. Harry Adam Schlotzhauer, who was at Stonehenge with Stanley, recalled that the latter insisted that he would fly Bristol Fighters.44

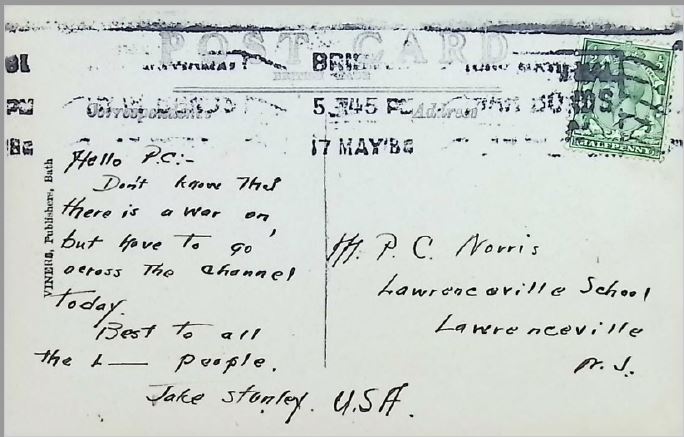

After finishing up at Stonehenge, Stanley, like a number of other second Oxford detachment members, became a ferry pilot assigned to the Central Despatch Pool in London and tasked with flying planes from place to place within England and from England to France. On a post card of Bristol Cathedral mailed to Norris on May 17, 1918, Stanley writes of having “to go across the channel today.”45

Two days later, Milnor, one of Stanley’s Exeter College roommates, now assigned to American Aviation Headquarters in London, wrote in his diary that he had gone that morning “to the [American Officers’] Inn with Doug [Stier]. Harry [Schlotzhauer], ‘Jake’ and Leach were there. We all had lunch and then sat around and talked till 3.30 when Doug and Jake left for Bristol to pick up a couple of Bristol Fighters for France.”

France and No. 11 Squadron R.A.F.

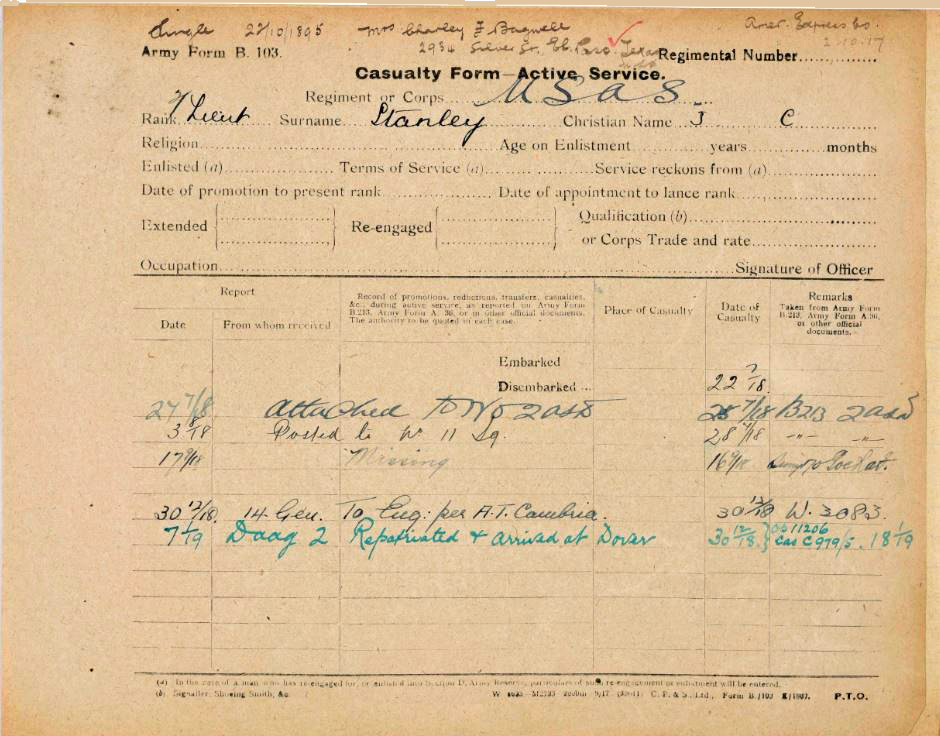

On July 22, 1918, Stanley was assigned to the British Expeditionary Force and travelled to France, to No. 2 Aeroplane Supply Depot.46 There, at the pilots pool at Rang du Fliers, about twenty miles south of Boulogne, he awaited orders to join a squadron. On July 28, 1918, he was posted to No. 11 Squadron, R.A.F. Stanley had gotten what he hoped for, assignment to a Bristol Fighter Squadron.

No. 11 Squadron had since early July 1918 been stationed at Le Quesnoy-en-Artois, only about twenty miles east-southeast of Rang du Fliers and the coast, and approximately thirty miles from Arras and the front.47 No. 11 was in the 13th (Army) Wing of III Brigade R.A.F., supporting the British Third Army, commanded by General Sir Julian Byng. The Third Army Front ran approximately from Arras south to Albert. Stanley was the only member of the second Oxford detachment assigned to No. 11, but he may well have encountered friends from the detachment at squadrons stationed nearby, in particular the American 17th and 148th Aero squadrons, which, starting in mid-August, were assigned to the British Third Army Front. The 148th, for example, to which Springs, and later Callahan, were assigned, was at Remaisnil, just thirteen miles southeast of Le Quesnoy.

I have been able to find little official documentation for No. 11 for the period when Stanley was serving with the squadron; there appears to be, for example, no extant squadron record book.48 The recollections of one of Stanley’s squadron mates, Norman Bruce Scott, however, provide some useful background. Scott first flew Bristol Fighters at Netheravon early in 1918; his description helps explain Stanley’s determination to fly this type of plane:

The Bristol handled beautifully. . . . It had a powerful, for those days, 190 H.P., water-cooled Rolls-Royce engine. This was later increased to 275 H.P. It was solidly built and we later learned could dive the wings off a Fokker. Our ceiling was about twenty thousand feet or a little better and top speed about one hundred and twenty or thirty miles per hour. But they felt as though they were full of purpose and gave one a sense of being well mounted as on a fine riding horse.49

Of the role of the Bristols at No. 11, Scott, who joined the squadron in mid-March 1918, writes:

While the name, Bristol Fighter, implied that we would be a combat squadron this was not the case as, at that time, our chief function was long-distance reconnaissance and photographing enemy positions far behind the lines. . . . But we had plenty of combat even though that was not our main purpose. The enemy didn’t want us photographing their ammunition and supply dumps and spotting their troop concentrations. We scarcely ever made a deep penetration without meeting enemy opposition and always, of course, at odds of their choosing, usually about four to one.50

He describe the types of patrols the squadron undertook:

The usual pattern of shows in our Squadron was a two-machine dawn patrol which . . . arrived at the front lines just before first light and spotted troop movements in and out of the trenches. . . . About an hour after the dawn patrol took off there was usually a reconnaissance patrol of, say four to six machines. They would fly back to Abbeville, on the coast, to gain altitude of about eighteen thousand feet and would then cross the lines and make a swing around the northern sector of our front, Arras, Douai, Denain and Cambrai. A second patrol usually left shortly after to cover southern sector, Adinfer, Bray, Bapaume, Peronne and the Somme Valley.51

Scott continues:

There were other patrols during the day and often we were required to furnish a fighter escort for the D.H.4s and D.H. 9s on their bombing missions. That usually meant about ten machines which would fly in two formations of five each one above and behind the other and both of which would take up station above and behind the bombers to ward off attack from enemy aircraft. These shows often led to wild dog-fights with fifty or sixty enemy scouts attacking the Bristol Fighters and the bombers.52

A notable instance of the squadron providing bomber escort occurred just days after Stanley’s arrival when, on August 1, 1918, the Bristol Fighters of No. 11, along with the S.E.5a’s of No. 60 Squadron flew protection for the planes of Nos. 3 and 56 in their successful raid on the German aerodrome at Epinoy. It seems unlikely that Stanley, being so new to the squadron and the front, would have taken part in this.

Finally, Scott notes that “Once or twice a week we would send up an offensive patrol which went looking for trouble. Usually six or eight machines in two flights, one above and behind the other, and the object was to search out a gaggle of Huns.”53

Stanley would have spent his first days at the squadron flying with an experienced observer who could point out important landmarks; they would have approached but not crossed the lines.54 Scott notes flying his first actual mission nine days after arriving at the squadron.55 If the same held true for Stanley, he would have been flying during the attack on the salient behind Amiens, which opened early in the morning of August 8, 1918, and which signaled the commencement of the Allies’ Hundred Days Offensive. The British Fourth Army and the French First Army, on the front to the south of Albert and the Third Army, were tasked with the attack, but planes attached to the Third Army, including those of No. 11 Squadron, also flew missions during the Battle of Amiens: “11 Squadron flew close offensive patrols and escorted bombing raids, leading to numerous combats.”56

Scott, meanwhile, was on leave in England from July 27 through August 10, 1918. He describes how, on his return to the squadron, “there was a new fellow in the opposite bunk in my tent . . . a handsome young American lad in the U.S. Airforce. . . . ” This was Stanley. “We got along very well and had a lot of fun playing catch and knocking out flies with a ball and bat and a couple of gloves we got from the Salvation Army.”. . ”57 (Scott was Canadian and was familiar with baseball as well as cricket.)

The Battle of Amiens was soon over; the much-weakened Germans having retreated before the onslaught. British forces needed to regroup after their quick advance led to their outrunning their supply lines. No. 11 Squadron, nevertheless, as documented by Scott’s log book, continued flying missions daily or almost daily, and it is safe to assume that Stanley was gaining a good deal of experience over the lines.

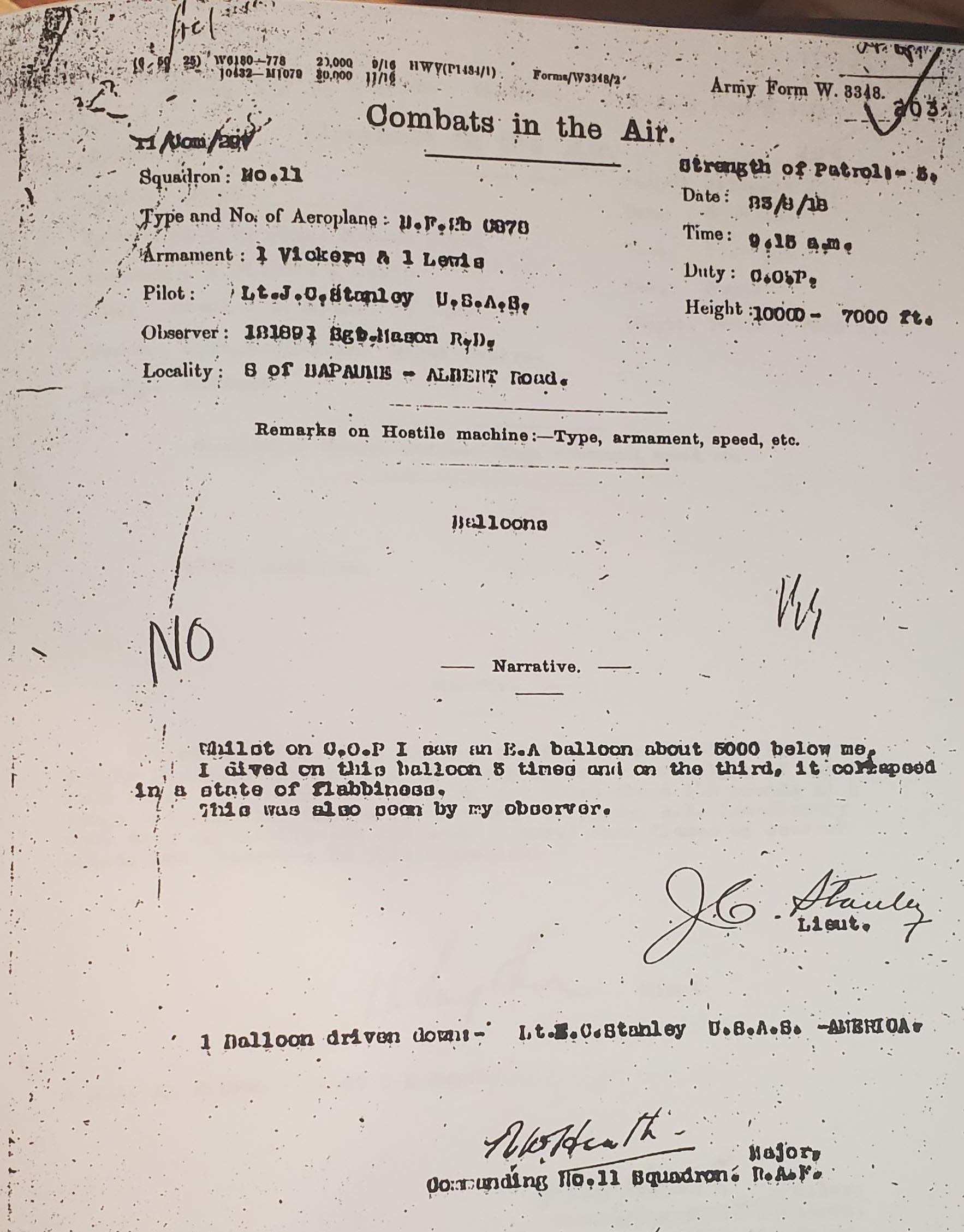

The next Allied offensive commenced on August 21, 1918, with the British Third Army tasked to recapture Albert, which it did the next day; a wider offensive began August 23, 1918, with the British Third Army advancing toward Bapaume. It was on this day that Stanley claimed a combat victory (whether this was his only one cannot be determined in the absence of better documentation for him and the squadron). According to the combat report that Stanley filed, he was one of 5 planes taking part in a close offensive patrol; he was flying B.F.2b C878, and his observer was Sergeant Richard Dudley Mason.58 Scott, flying B.F.2b C775 with his observer, Lawrence William King, flew one of the other planes. Scott recorded in his log book that the patrol, which lasted two hours and forty-five minutes, set out at 7:40 a.m. on a course “Adinfer. Achiet. Bapaume. Albert,” flying at 10,000 feet, and that he saw twenty-five German planes, “didn’t attack.”

At 9:15, “S[outh] of Bapaume – Albert Road,” Stanley “saw an E.A. balloon about 5000 below me. I dived on this balloon 3 times and on the third, it collapsed in a state of flabbiness. This was also seen by my observer.”59 Stanley did not receive credit for this in American records, perhaps because of poor communications or perhaps because he was not credited with it by the British: there is a (to me) ambiguous “No” written on the combat report.

Bapaume was captured on August 29, 1918. On this day for the first time Scott noted flying a course that included “Cambrai,” and this continued to be an objective throughout early September as the British Third Army continued to push east. Weather precluded patrols from September 7 through the 14th. On the, 15th and 16th Cambrai was again the objective for photo reconnaissance and escort work.

On the 15th Stanley, having just received a letter from P.C. Norris, wrote back to him. He notes that “I am with the British and mighty glad of it for the time being. Best experience in the world to work out with ‘one who know[s]’. Expect that is the reason why I am not pushing daisies now. . . . I am soon to go to an American Squadron. . . . Have been shot up quite badly on several occasions. However, I gave tit for tat and managed to get home. That’s what really counts. . . . I am flying Bristol fighters—Best machine on the front.”60

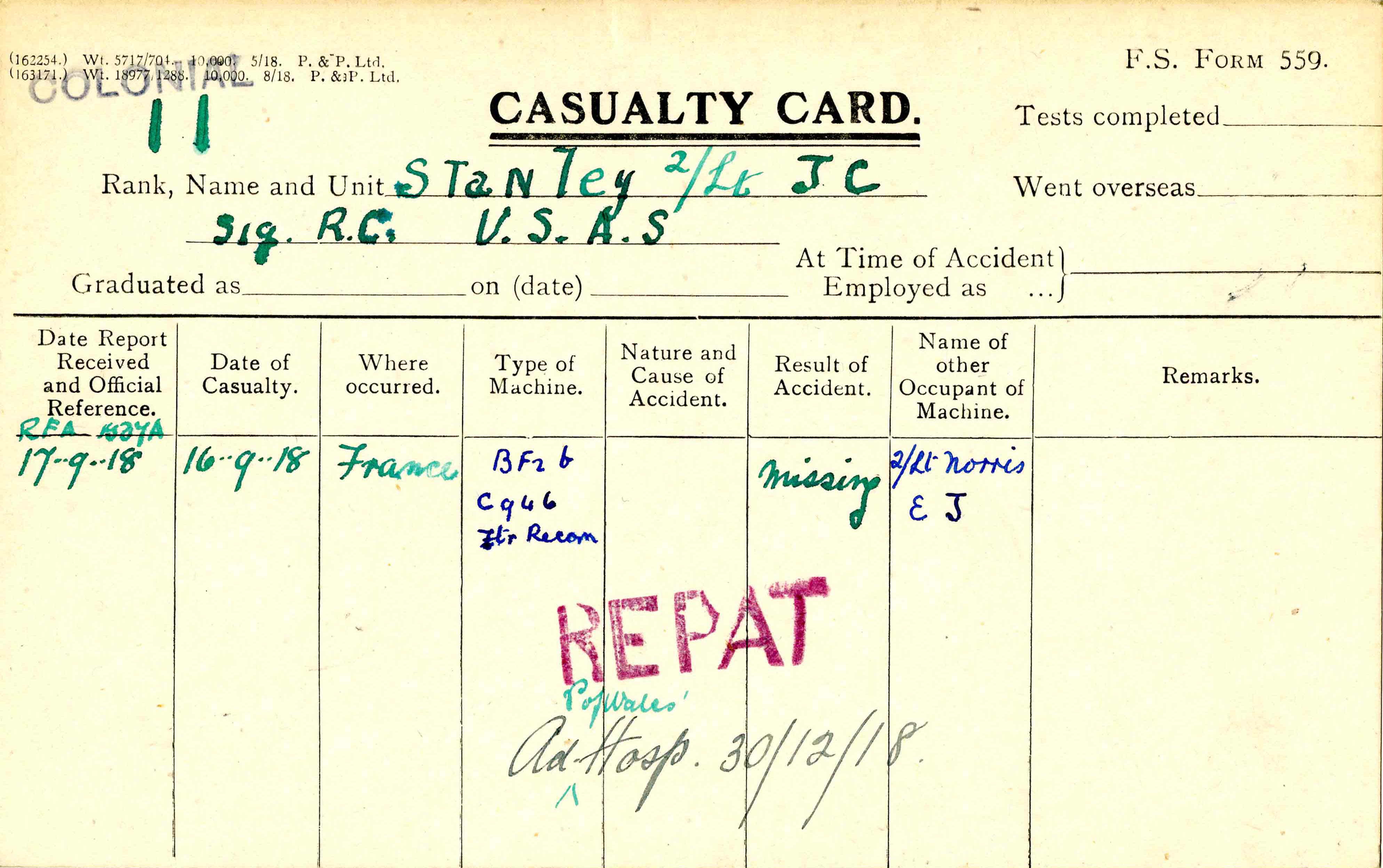

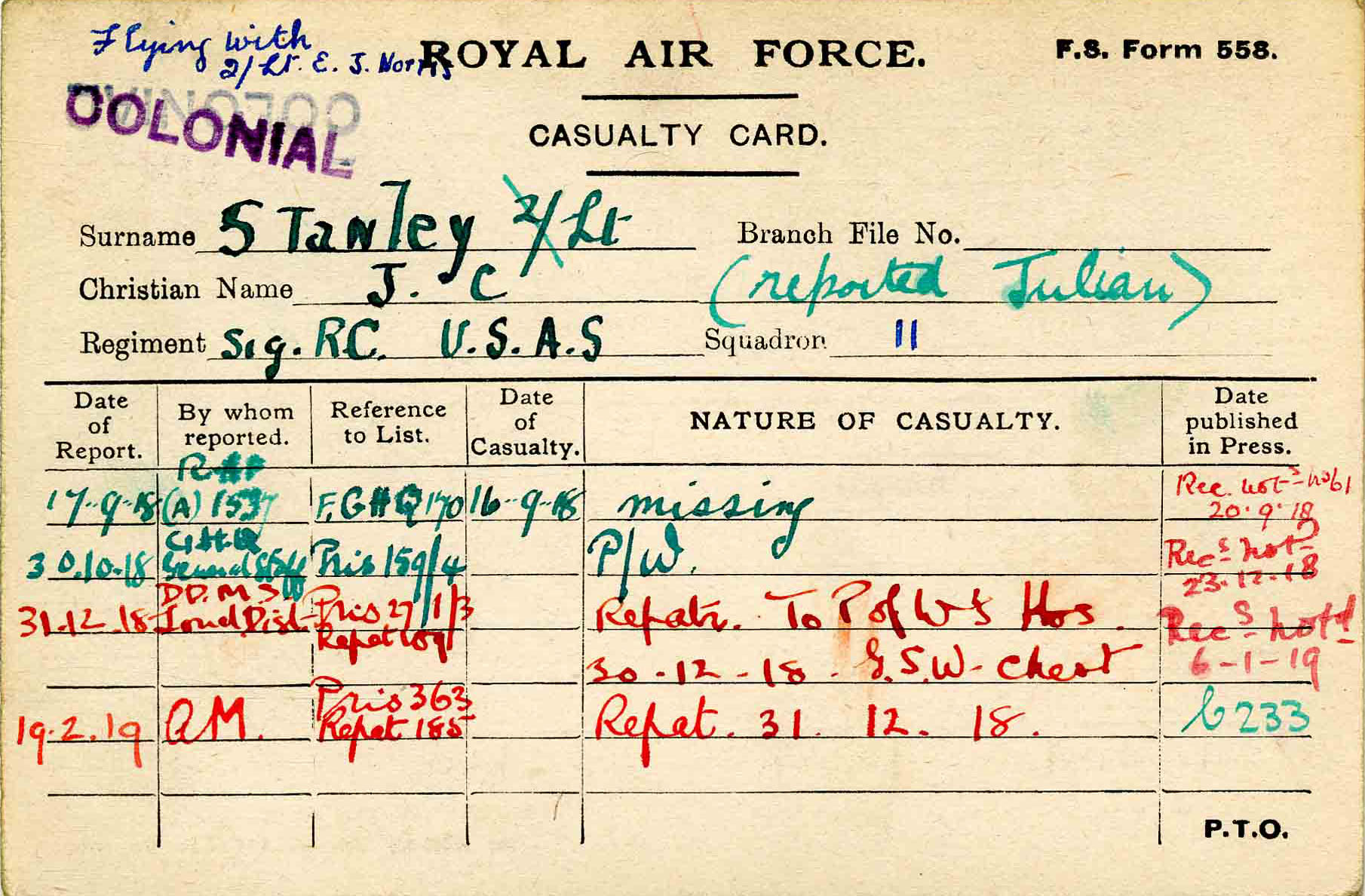

At 7:00 a.m. on September 16, 1918, ten planes from No. 11 Squadron set out on a reconnaissance patrol.61 Stanley was flying F.E.2b C946 with observer Edwin John Norris. Others on the patrol included Scott with his regular observer King, Eugene Seeley Coler with observer Edward James Corbett, and Leslie (“Jake”) Arnott with observer George Leonard Bryars.

The patrol flew beyond Cambrai at an altitude of 17 or 18,000 feet to, according to Scott, Beauvois-en-Cambrésis; as far as Le Cateau-Cambrésis, according to Stanley.62 In the latter case, they would have been a good twenty miles deep into German-held territory.

Coler’s combat report records that at approximately 8:30 a.m. the Bristol Fighters of No. 11 Squadron were attacked by “25 to 30 Fokker Biplanes and Pfaltz Scouts.” Coler turned back east and fired at one of them that was attacking another Bristol, but Coler was in turn attacked by several Fokkers; his plane sustained such damage as forced him to dive and eventually crash land in friendly territory. Meanwhile Arnott and Bryars were shot down, perhaps at 8:45 over Fontaine-en-Pire.63 Apparently a few minutes later, it was Stanley’s turn. Scott recalled that “I wasn’t a hundred feet from him [Stanley] when he got hit. His engine was dead but he wasn’t on fire and I could see that he was still sitting up and flying the machine. I followed him down a couple of thousand feet to see him safely out of the dog fight but then had to let him go.”64

Stanley provided the following account:

. . . the squadron was returning to the line when we encountered fifteen to twenty enemy aircraft who attacked our flight from behind and below. Seeing the machine on my right [Arnott’s?] go down in a spin I went back to engage the enemy aircraft. After returning and encountered [sic] the enemy aircraft, I fired a burst of fifty rounds into the closest machine who started down out of control. Was unable to follow this machine on account of being attacked by other enemy aircraft diving from above who put a burst into my petrol tanks and the motor failed. Controlling the machine as best I could, I attempted to cross the line, giving my observer every opportunity to fire at the enemy aircraft. I was then wounded in the hand and side. My observer was also hit, but continued to fire against enemy aircraft, and to my belief, succeeded in sending one down out of control and force another to glide down. Five enemy aircraft followed us all the way down from 18,000 feet firing the whole time. Near the ground my machine was set on fire by a tracer bullet from enemy aircraft. My machine, going down out of control, crashed, and we were taken prisoners by the German Infantry.64a

Scott surmised his friend’s fate and “took a chance and wrote his mother that I felt sure he was a prisoner, maybe slightly wounded, but certainly not killed.”65

Stanley provided another account of his remarkable survival and that of Norris in the diary that he kept as a prisoner of war.66 The entry for September 16, 1918, indicates that after his gas tank was punctured, he “dove for” the Bois de Havrincourt but was too far away to get across the lines. “Eng[ine] failure, and observer shot in 5 places—myself twice. Machine in flames! Thrown clear—but both on fire.”67

There is yet another, more detailed, albeit second-hand, account of Stanley’s crash landing in a letter written to P. C. Norris by his fellow Lawrenceville teacher, Edwin William Pahlow. Pahlow visited Stanley in an American Red Cross Hospital in England in early February 1919.

[Jake] told me a little about his last fight. In it, he became separated from the rest of his squadron and had five machines after him. Early in the game (while still high in the air) his engine was put out of commission so there was nothing to do but to glide and side-slip, fighting of course all the time. . . . Besides putting Jake’s engine out of commission, the Boches punctured his petrol tanks, so all the time they were gliding down a spray of petrol was enveloping them and when they were about 100 feet from the ground it burst into flame. Jake side-slipped at once and crashed, but both he and his pal [Norris] had loosened their belts and so were thrown free from the machine. Both were in flames, but Jake, who had only two bullets (one through his left lower arm and the other through his right side) was able to get up and slip out of his blazing heavy coat and helmet and go to the rescue of his pal, who had been shot nine times, and both of whose arms and legs were broken.68

The day after the crash, September 17, 1918, Stanley and Norris were taken to Cambrai and thence to a hospital in Bouchain, where Norris’s leg was amputated.69 Stanley noted that at Bouchain they were “Treated kindly and well by the Germans.” Stanley was also fortunate to be tended by a French woman to whom he was particularly grateful for some cakes and tobacco. A few days later, a German doctor removed the bullet in Stanley’s back; his injured hand continued to be very painful. Stanley was taken on the 23rd to Denain. Norris remained behind in Bouchain until the 28th, when he, too, arrived in Denain; they remained there until October 4, 1918. Stanley recounts the arrival of other P.O.W.s and notes the eastward movement of the front line and Denain being bombed.

In early October Stanley and Norris were transported via Belgium to Aachen where, after a long period without treatment, Stanley’s wounded hand was redressed before they entrained again. On the 7th they arrived at a prison hospital in Göttingen, where they remained for over two months. Stanley was glad to find an American doctor there, a Dr. [Harold Arrott] Goodrich from St. Louis.70 On October 8, 1918, Stanley wrote that “Norris my observer, goes to Blighty, as he has an amputation,” but this transfer did not happen, for Stanley’s entry for October 22, 1918, reads in part “Norris much better. Plucky fellow and cheerful. His amputation is doing very good.”

Stanley’s diary entries grew shorter as the tedium and discomfort took their toll, not to mention the deaths of some fellow prisoners and Stanley’s contracting “grippe”—probably Spanish flu—and an eye infection. News of the Armistice arrived and was celebrated. More than another month of more tedium followed, but, finally, around mid-December, Stanley and Goodrich departed Göttingen together, bound for Cassel; Norris appears to have gone on separately to a British Casualty Clearing Station and thence to England.71

On Christmas Eve, Stanley, along with many other P.O.W.s, boarded a Red Cross train bound for Cologne and then Boulogne. The A[mbulance] T[ransport] Cambria transported him to Dover on December 30, 1918,72 and he was then admitted to the Prince of Wales Hospital in London.

“To cap the climax I was taken ill with pneumonia and remained in bed for another month and a half.” According to Pahlow, in his letter to his colleague Norris, “Jake went to a dance, overdid it, and next morning found himself laid up with pneumonia.” By this time (February 10, 1919) Stanley had been transferred to the American Red Cross Military Hospital No. 22 in Bayswater.73

Stanley sailed for the U.S. from Southampton on February 27, 1919 on the Mauretania; he, along with fellow second Oxford detachment member Harvard de DeHart Castle, was part of a small “convalescent detachment” of officers from American Red Cross Hospital No. 22. On arrival in New York on March 6, 1919, he, Castle, and several others were sent to Lafayette House, the officers’ annex of Debarkation Hospital No. 5.74 Another Lawrenceville student, John Cassidy Muñoz, wrote to Lawrenceville teacher Norris in May of 1919, reporting that Stanley had “been in Jacksonville. ‘Jake’ as you know was wounded and went to John [sic] Hopkins for an operation on his arm the bullett [sic] damaged him went through the back of his wrist coming out in the palm of his hand. Did not know the out come of this operation, but understand that he is now in New York but not discharged.”75 An official New York record indicates that Stanley was honorably discharged from the service on October 24, 1919, and was thirty per cent disabled.76 An account in the Yale Alumni Weekly states that he was discharged from hospital the next day.77 Nettleton’s Yale in the World War list his injuries: “stiff left arm from machine gun bullets; fractured rib; impaired vision left eye.”78

The 1920 census, taken in January, shows Stanley residing with his old friends the Charles Buxton Rogers family in Jacksonville; he is described as a student, presumably finishing up his Yale degree.79 September of that year finds him in Arizona, where he applied for a passport to allow him to pursue ranching interests in Sonora, Mexico. 80 The passport application gives his residence as New York City. When he married in Manhattan in 1929, Elliott White Springs was one of the ushers at the wedding.81 Stanley remained in New York where he was an insurance and stockbroker.82

mrsmcq August 8, 2025

Notes

(For complete bibliographic entries, please consult the list of works and web pages cited.)

1 Stanley’s place and date of birth are taken from Ancestry.com, U.S., World War I Draft Registration Cards, 1917–1918, record for Julian Carr Stanley. His place of death is a reasonable surmise based on residence records and Ancestry.com, U.S., Social Security Death Index, 1935–Current, record for Julian Stanley. His date of death is taken from Ancestry.com, U.S., Department of Veterans Affairs BIRLS Death File, 1850-2010, record for Julian Carr Stanley. The photo is a detail from a large group photo of cadets at Christ Church College, Oxford, where Stanley is in the second row from the bottom, ninth from right.

2 Ancestry.com, North Carolina, U.S., Land Grant Files, 1693-1960, record for Jno C Stanaland.

3 This information is based mainly on Adam Broxton’s “Adam Croft Broxton,” and on an excerpt (page 1) of Schuyler D. Stanaland’s “Meet the Stanalands,” both works of unknown reliability.

4 See “Our Washington Letter.”

5 Her first and last names are variously spelled, and I have been able to discover nothing about her paternal ancestry. I have taken the spelling used in the will of her maternal grandfather, William Bell Robeson. See Ancestry.com, North Carolina, U.S., Wills and Probate Records, 1665-1998, record for William B Robeson.

6 Stanley, Jr., “Prisoner in Germany,” p. 341.

7 “Mrs. J. C. Stanley Dead.”

8 Ibid.

9 Stanley, Jr., “Prisoner in Germany,” p. 341.

10 See J. C. Stanley’s student record at The Lawrenceville School.

11 See J. C. Stanley’s student record at The Lawrenceville School for this and the following information about his schooling; also, Stanley, Jr., “Prisoner in Germany,” p. 341.

12 “Appointments for Military Academy.”

13 Alumni Directory of Yale University 1920, pp. 332 and 899; The Yale Banner and Pot-Pourri, vol. 10, p. 427.

14 “First Battery Muster,” p. 5; “Yale Field Artillery.”

15 “Aero Corps Begins Training Saturday.”

16 Ibid.

17 Ibid.

18 National Archives (UK), Royal Air Force officers’ service records 1918–1919, record for Julian Carr Stanley. And see The Lawrenceville School, Student record of Julian Carr Stanley.

19 Ancestry.com, Connecticut, U.S., Military Census, 1917, record for Julian Carr Stanley. On the Connecticut troops ordered to the Mexican border, see references to “1st Connecticut” in various Connecticut newspapers from June and July 1916.

20 “Yale is Sending Half of Students into the Ranks.”

21 See Stanley’s draft card, cited above.

22 “El Pasoans out of City Who Registered by Mail.”

23 Stanley, “Prisoner in Germany,” p. 341.

24 “Ground School Graduations [for August 25, 1917].”s

25 Grider, Diary September 20–October 1, 1917.

26 Winslow, RFC/RAF No. 56 Squadron Diary of Paul Winslow, entry for October 2, 1917. Inexplicably, Winslow indicates that the two men were at Exeter on October 1, 1917.

27 Skelton, Callahan, the Last War Bird, p. 5.

28 Ibid.

29 The event is recorded under the date October 22, 1917, in both Grider’s diary and in War Birds, although it is clear from other accounts that the party took place on October 20, 1917.

30 Milnor, diary entry for October 22, 1917.

31 See Hooper, Somewhere in France, letter of October 27, 1917, and Clements, diary (autograph manuscript) for October 25 and 26, 1917.

32 Clements, diary entry for October 26, 1917.

33 Springs, Letters from a War Bird, p. 44. See this letter also for another account of the October 20, 1917, celebrations.

34 War Birds, entry for November 6, 1917. Springs wrote about how difficult the choice was in his letters home, but does not specify the criteria (see his letter of November 6, 1917, in Springs, Letters from a War Bird); contrary to the statement in War Birds, not all of the twenty men had flown.

35 See Neely’s and Deetjen’s diary entries for this date.

36 Neely, diary entry for November 6, 1917. Springs, probably mistakenly, indicates the incident took place the preceding day; see Springs, Letters from a War Bird, p. 49.

37 See Neely’s Pilot’s Flying Log Book and Springs, Letters from a War Bird, p. 54.

38 Stanley, Letters.

39 See Deetjen’s diary entry for January 18, 1918.

40 See Stanley, Letters. I find no R.F.C. casualty card associated with this incident.

41 See Pershing’s cable 678-S, dated March 4, 1918. There was always a lapse of some days between the recommendation by the cadet’s squadron and Pershing’s cable forwarding the recommendation to Washington.

42 Biddle, “Special Orders No. 35.”

43 There is an unclear (to me) entry on Stanley’s R.A.F. service record that may indicate that on April 2, 1918, he was at Marske.

44 Col. Harry A. Schlotzhauer, tape 1, side a, ca. 00:20:43.

45 Stanley, Letters.

46 See Stanley’s R.A.F. service record, cited above, and his casualty form: “2nd Lieut. J C Stanley USAS.” It is puzzling that both British documents give Stanley’s rank as a second lieutenant, while it is clear from American documents that he had been appointed a first lieutenant (see, for example, Cablegrams 678-S and 979-R.

47 See the entry for No. 11 Squadron in Jefford, RAF Squadrons.

48 See “No. 11 Squadron RFC,” where Henshaw comments that “I’ve always found the material about 11 Sqn somewhat elusive, especially the earlier stuff.” I have not had access to the (not yet digitized) Operations Record Book (Air 27 / 157, at The National Archives [UK]); the history of No. 11 Squadron in 1918 in the relevant Appendix (TNA Air 27 / 161, pp. 308–10) is cursory.

49 Scott, “Diary of a War Bird,” p. 12. The title is slightly misleading, as this is less a diary than recollections based, perhaps, on a diary.

50 Ibid., pp. 15 and 16.

51 Ibid., p. 17. It was presumably while the squadron was stationed at Fienvillers and Remaisnil that they flew to Abbeville to gain height, but presumably at Quesnoy, somewhat to the north, an initial altitude-gaining leg towards the coast was still the practice.

52 Ibid., p. 18.

53 Ibid., p. 18.

54 Cf. Ibid, p. 16.

55 Ibid., p. 21.

56 From a history of No. 11 Squadron, unpublished, by Trevor Henshaw, a portion of which Henshaw sent me in May 2025. In the absence of the squadron record book, knowledge of the squadron’s missions during this period is presumably based largely on victory claims and casualty reports.

57 Scott, “Diary of a War Bird,” pp. 38–39.

58 Stanley, Combat report.

59 Ibid.

60 Stanley, Letters.

61 Norman Bruce Scott, Pilot’s Flying Log Book (time); Coler, Combat report (number).

62 See Scott’s log book and Stanley’s account on p. 280 of Presenting the Experiences of Air Service Officers who were Prisoners of War in Germany, as well as the relevant entries in Henshaw’s The Sky Their Battlefield.

63 See the entry in Henshaw, The Sky Their Battlefield. NB: Record keepers have not done well by Bryars. His casualty form gives his middle name as “Leonnard” (see “2nd Lieut. George Leonnard Bryars RAF”); his RAF service record is entered in the National Archives (UK) online catalogue under the last name “Bryas,” although this has been corrected on the original; see The National Archives (UK), Royal Air Force officers’ service records 1918–1919, record for George Leonard Bryas. Finally, the entry for Bryars at the Commonwealth War Graves Commission web site has him in No. 20 Squadron rather than No. 11; see “Flight Lieutenant George Leonard Bryars.”

64 Scott, Diary of a War Bird, p. 39.

64a Presenting the Experiences of Air Service Officers who were Prisoners of War in Germany, p. 280.

65 Scott, The Diary of a War Bird, p. 39.

66 This has been transcribed by his son, Julian Carr Stanley, Jr., in “Prisoner in Germany.” If the senior Stanley had the habit of daily diary entries whilst a prisoner, it seems probable that he also, like many men in the detachment, had started the practice when he set out for Europe. Unfortunately the early diary has apparently not survived, perhaps destroyed when his effects were gathered by his squadron mates after Stanley went missing. The loss is unfortunate not just for lost information but because Stanley’s style is lively and engaging, reminiscent of the voice Springs used in War Birds.

67 Stanley, Jr., “Prisoner in Germany,” p. 342.

68 See page 1 of Pahlow’s letter dated February 10, 1919, in Pahlow, Letters.

69 Information regarding the P.O.W. experiences of Stanley and Norris and their return to England and then Stanley’s to the U.S. is based, unless otherwise noted, on the transcription of his diary in Stanley, Jr., “Prisoner in Germany.”

70 “Webster Groves Doctor Prisoner in Germany.”

71 “2nd Lieut. E.J. Norris.”

73 Pahlow’s letter dated February 10, 1919, in Pahlow, Letters.

74 Ancestry.com, U.S., Army Transport Service, Passenger Lists, 1910-1939, record for Julian C. Stanley.

75 Muñoz, Letters, letter of May 13, 1919.

76 Ancestry.com, New York, Abstracts of World War I Military Service, 1917–1919, record for Julian C Stanley.

77 “Alumni Notes,” Yale Alumni Weekly, p. 294.

78 Nettleton, Yale in the World War, vol. 2, p. 462.

79 Ancestry.com, 1920 United States Federal Census, record for Julian C Stanley.

80 Ancestry.com, U.S., Passport Applications, 1795–1925, record for Julian C Stanley.

81 “In Town.”

82 See, for example, Ancestry.com, 1950 United States Federal Census, record for Julian C Stanley.