(Rockland, Massachusetts, June 6, 1894 – South Weymouth, Massachusetts, September 18, 1967).1

Leo McCarthy’s grandparents came to the U.S. from Ireland and settled south of Boston. His father, John Joseph McCarthy, began working in a shoe factory in Rockland, Massachusetts, and rose to the position of foreman. He married Margaret F. Ahearn in 1881; the 1900 census shows four children, with Leo the third child and older of two sons.2 Leo McCarthy studied business administration at Boston University while working in the E. T. Wright and Co. Shoe factory; his draft registration records that he was a department manager there.3 He attended ground school at M.I.T. and was one of a group of eight men recorded as having graduated September 1, 1917.4

Of those eight, six—McCarthy, John Lavalle, Jr., Phillips Merrill Payson, Andrew Joseph Shannon, George Dana Spear, and Perley Melbourne Stoughton—chose or were chosen for training in Italy, and these six were among the 150 members of the “Italian” or “second Oxford detachment” who sailed to England on the Carmania. The ship left New York September 18, 1917, made a brief stop at Halifax, and then crossed the Atlantic as part of a convoy. “At the end of our voyage came the order which, at that time seemed to blight our young lives. The American authorities here had changed our orders so that we would be trained with the R.F.C.”—this is McCarthy’s description of learning, when the Carmania docked at Liverpool on October 2, 1917, that they would not proceed to Italy but remain in England.5 He goes on: “And worse, we were put in the ground school at Oxford University for four weeks.” While the cadets, as they were now designated, repeated ground school at the Royal Flying Corps’s No. 2 School of Military Aeronautics at Oxford they were initially housed at Christ Church College, under Elliott White Springs, and at Queen’s College, under William Ludwig Deetjen.6

McCarthy appears to have been in the Queen’s College group and to have roomed with his ground school classmate Spear and with Fremont Cutler Foss, who had attended ground school at Ohio State University. Foss recounts how he, Spear, and McCarthy were conversing late one evening when “A knock sounded at our door. ‘Ten shun’ called Adeley and in walked Major Robinson U.S. Also a British staff officer, Captain Drexel and Lieutenant Dwyer. They asked us how we liked the place, whether we were learning anything etc. McCarthy was our spokesman and of course he answered ‘yes.’”7 Gerald Graham Adeley was Assistant Commander of the S.M.A. at Oxford; Robinson was probably Gordon Robinson, a West Point man; John Armstrong Drexel and Geoffrey Dwyer represented the Aviation Section of the Signal Corps in Great Britain—altogether a formidable delegation.8 Major Robinson proceeded the next day to inspect the cadets of both the first and second detachments of Americans at Oxford. The relevant entry in War Birds reads in part: “This major had a parade of both outfits and inspected us and then got us in the mess-hall and pitched into us as if we were convicts. He said he had heard that we were grousing because we had to go to Ground School again and hadn’t gotten our commissions as we had been promised. He said if any of us didn’t like it, he would send us over to France and send us up to the trenches as privates. . . . He didn’t like our uniforms. He said they were all right at home but they wouldn’t do over here where everybody has to be smart. So we’ve got to buy tailor-made uniforms and pay for them ourselves . . . and any man who refuses to buy one of these special uniforms, is to be sent to France for discipline.”9 American campaign hats were replaced with R.F.C. caps, and the men started wearing General Pershing-approved Sam Browne belts.

On November 1, 1917, the second Oxford detachment men learned from Dwyer that 130 of them would go to machine gun school at Grantham in Lincolnshire, while twenty would begin flight training at Stamford.10 Foss wrote in his diary the next evening that “Before supper Perley [Stoughton], Mac [McCarthy], [Donald Swett] Poler, [Frank Aloysius] Dixon, and myself went to canteen and drank five rounds. Orders were issued for all baggage to be ready by 7 P.M.” On November 3, 1917, they all, with the exception of Dixon, who was to go to Stamford, made the six-hour train journey to Grantham and then settled in at Harrowby Camp, the machine gun school located just to the northeast of Grantham in the park belonging to Belton House. Not long after arriving, McCarthy wrote appreciatively that “we’ve landed in a mighty fine place. Although our own government considers us cadets still the authorities here have placed us on the status of officers. Officers mess, good service and wonderfully good food, orderly to take care of our ‘hut’ . . . The studies here we also find very interesting.”11 Fifty of the men departed on November 19, 1917, for flying schools; McCarthy was among those who remained at Grantham through Thanksgiving and completed two two-week machine gun courses, the first on the Vickers, the second on the Lewis machine gun.

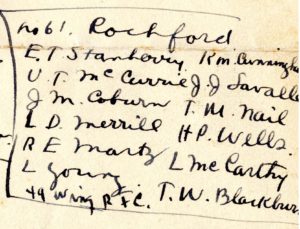

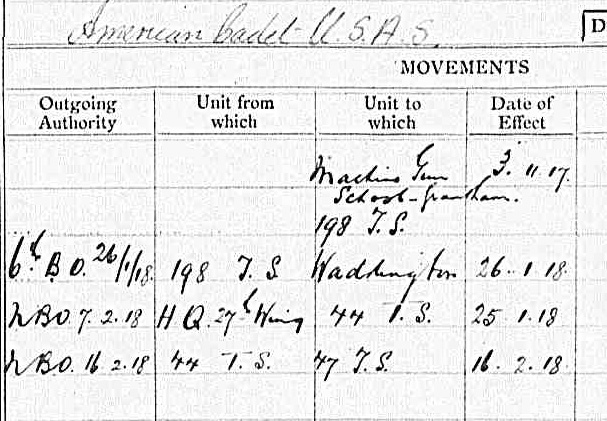

In December, finally, the cadets still at Grantham were sent to training squadrons. McCarthy was posted, along with eleven others (Thomas Welch Blackburn, Jr., James Mitchell Coburn, Kenneth MacLean Cunningham, Lavalle, Roy Edwin Martz, Uel Thomas McCurry, Linn Daicy Merrill, Thomas M. Nial, Elwood D. Stanbery, Horace Palmer Wells, and Louis McComas Young), to Rochford in Essex. The initial assignment was apparently to No. 61 Squadron, a home defense squadron flying S.E.5a’s.12 However, at least some of the eleven, including McCarthy, were reassigned to No. 198 Night Training Squadron, also at Rochford.13 Neither squadron was, on the face of it, intended for the training of novices, but the men evidently got some time in the air. McCarthy, in an undated letter to his father, mentions “one of the instructors at Rochford,” and entries in his R.F.C. Training Transfer Card indicate that while he was a t No. 198 McCarthy put in over five hours flying dual in an Avro and twenty-five minutes in a B.E.2e.14

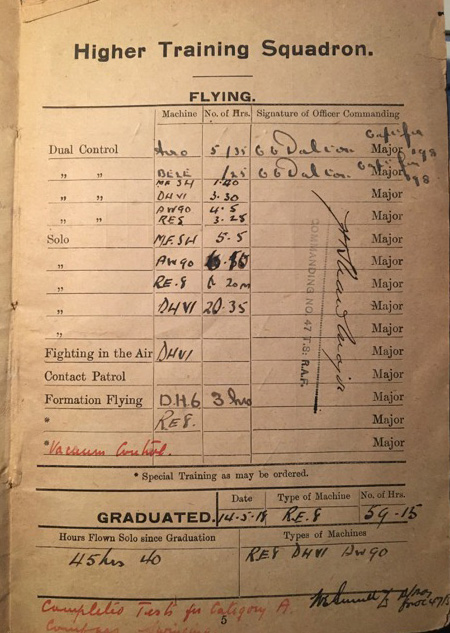

On January 26, 1918, McCarthy was posted from Rochford to Waddington in Lincolnshire, initially to No. 44 Training Squadron.15 Deetjen, who had ten days previously been posted from Stamford to Waddington, noted in his diary that around the time McCarthy arrived “A whole lot of our bunch came from Stamford and all over. We must number about 30.”16 A short while later, on February 6, 1918, Deetjen wrote that “McCarthy of ground school moved in with us tonight.” Ten days later McCarthy was assigned to No. 47 T.S. at Waddington.17 William Thomas Clements, also at No. 47, called it a “Rumpety squadron”—the Maurice Farman Shorthorn, commonly known as a “Rumpty / Rumpety” was an obsolete two-seater pusher biplane much used in training at this time. By March 8, 1918, McCarthy had flown this plane for an hour and forty minutes with an instructor and nearly six hours solo.18

McCarthy and Deetjen were evidently given leave from Wednesday, March 6, 1918, through the weekend, and they spent the time in London. They played tourist (“Westminster Abbey, Houses of Parliament, Bank of England, Strand, Pall Mall and the rest o’ London”), shopped, socialized, and enjoyed several shows as well as “Warm beds, hot bath, and late breakfasts.” Late Thursday evening “there was a Gotha air raid at about 11:30 P.M. ’Twas a first all the way throughout. Darned cheap advertising, these Huns play. When we heard the warning—auto klaxons—Mac and I hopped for the windows and hung there for an hour.” “Sunday at 11:40 A.M. Mac and I laughed and packed ourselves off. At Peterborough he changed for Waddington while I went on to Nottingham.”19

The next day was, according to Clements’s diary entry, “dud,” i.e., the weather was too bad for flying. Over the next few days, however, both Clements and Foss got in quite a bit of flying, but for some reason McCarthy did not.20 Deetjen wrote in his diary on March 18, 1918, that “At 9:30 Lt. Brandon of 51 T.S. loaned me a deH6 for 15 minutes and I ran over to 47 T.S. and picked up Mac. Poor devil has not been up for three weeks. I let him monkey around for a while and then gave him some instruction. The bus was returned (after dropping Mac) after 40 minutes. No one was the wiser and Mac learned something too.”

Not long after, things evidently began to pick up. McCarthy writes towards the end of March that he “went solo on the intermediate bus. The same day I did 3¼ hours solo—altogether 4 hours in the air in one day.”21 He presumably does not name the intermediate bus type because of censorship rules; he was perhaps now piloting a D.H.6, the two-seater training plane that Deetjen had flown him in, or an an Armstrong Whitworth FK.3—both are listed on his R.F.C. Training Transfer Card as planes he flew solo.22 He noted that he needed “only 11 hrs more flying to do in order to get my ‘commish’ or wings.”

The recommendation for McCarthy’s commission was forwarded to Washington on April 8, 1918.23 However, the recommendation stipulates that he and a number of American Oxford cadets should be commissioned “First Lieutenants Aviation Reserve non flying.” The “non-flying” status apparently arose from an effort by Pershing to rectify an injustice. In a cable to Washington dated March 13, 1918, the commander in chief of the American Expeditionary Force described the situation of the approximately 1400 aviation cadets in Europe, some of whom had waited three months to start flying training, and some of whom, after five months, were still waiting and might have to wait another four.24 “All of those cadets would have been commissioned prior to this date if training facilities could have been provided. These conditions have produced profound discouragement among cadets.” To remedy this injustice, and to put the European cadets on an equal footing with their counterparts in the U.S., Pershing asked permission “to immediately issue to all cadets now in Europe temporary or Reserve commissions in Aviation Section Signal Corps. . . .” Washington approved the plan in a cable dated March 21, 1918, but stipulated that the commissioned men be “put on non-flying status. Upon satisfactory completion of flying training they can be transferred as flying officers.”25

Washington took its time responding, and on April 30, 1918, Pershing wrote: “Request action taken on . . .” and lists cables dated March 29 through April 8, 1918. The confirming cable from Washington, finally, is dated May 13, 1918.

By this time McCarthy had almost certainly earned the right to be among those “transferred as flying officers.” The next day (May 14, 1918) he graduated from this stage of R.F.C. / R.A.F. training, with nearly sixty hours of flying, including, if I read his R.F.C. Training Transfer Card correctly, an hour and twenty minutes on a service (as opposed to training) plane, an R.E.8. He was placed on active service on May 28, 1918.26

Meanwhile, he was “Just a little lonesome . . . My bunkie, best friend & pal left yesterday for an aerial gunnery course.”27 Deetjen had departed for Marske-by-the-Sea in Yorkshire on April 4, 1918. Entries in McCarthy’s R.F.C. Training Transfer Card suggest that he remained at No. 47 T.S. in Waddington through at least the end of June 1918.

In a letter written in early April 1918 McCarthy reports that he had been asked by his instructor “why I didn’t put in application for transfer to scouts. He claims I’ve got just the right touch for scouts and that I don’t seem to be afraid to throw the bus around in the air.”28 Whether McCarthy did ask for such a transfer is not evident, but the little further available documentation of his training makes clear that he continued on courses for two-seater bomber and observation plane pilots. His R.A.F. service record indicates he was posted on October 14, 1918, from the No. 1 School of Aerial Navigation and Bomb Dropping at Stonehenge in Wiltshire to U.S.A.S. H.Q. London.

He had evidently received training on D.H.4s, as he was posted at the end of the month to the U.S. 8th Aero Squadron, an observation squadron flying D.H.-4s.29 The 8th Aero was by now stationed at Sazerais, about ten miles northeast of Toul. It had been supporting the American First Army, but was now assigned to the Air Service of the recently formed American Second Army. While at Saizerais, the 8th Aero undertook photographic and voluntary bombing missions.30 I have been unable to find operations reports that might provide details of individual flights and thus document McCarthy’s participation. It was intended that the Second Army would “begin a general offensive leading to the capture of Metz and the gateway into Germany proper.”31 The armistice supervened.

McCarthy was back in his home town of Rockland by May 1919.32 He resumed working at E. T. Wright & Co., from which he retired as the company’s president in 1966.33

mrsmcq April 20, 2017

Notes

(For complete bibliographic entries, please consult the list of works and web pages cited.)

1 For McCarthy’s place and date of birth, see Ancestry.com, U.S., World War I Draft Registration Cards, 1917–1918, record for Leo McCarthy. On his place and date of death, see “Leo McCarthy, 73: Shoe Company President.” The photo is (cropped) from a formal portrait photo; see full image here. This and the other images on this page (excepting the detail from Foss’s diary and the portion of McCarthy’s R.A.F. service record) were supplied by McCarthy’s grandson, who kindly gave permission for their reproduction.

2 Ancestry.com, 1900 United States Federal Census, record for Leo McCarthy.

3 See Boston University, The Year Book 1917–1918, p. 211, and the draft registration cited above.

4 “Ground School Graduations [for September 1, 1917].”

5 McCarthy, letter of November 6, 1917. Various reasons have been put forward for the change of plans. See, for example, Hadley, “Foreign Aviation Detachments,” p. 4 (286), Dwyer, “Report on Air Service Flying Training Department in England,” p. 2, and Sloan and Hocutt, “The Real Italian Detachment,” p. 44. Dwyer, who would surely have been the person best positioned to know what had happened, only reports that the detachment “had their orders revoked.”

6 Deetjen, diary entry for October 4, 1917.

7 Foss, diary entry for October 13, 1917.

8 On Adeley, see “Regular Forces,” p. 10490. On Drexel and Dwyer, see Murray, Air Service History, p. 77. On Gordon Robinson, see Cullum, Biographical Register, pp. 962–63, and Alden Rogers, The Hard White Road, p. 6.

9 War Birds, entry for October 16, 1917.

10 Foss, diary entry for November 1, 1917. 129 men actually went to Grantham; according to the War Birds entry for November 6, 1917, James Whitworth Stokes stayed behind in Oxford to be operated on for appendicitis.

11 McCarthy, letter of November 6, 1917.

12 For the assignment to Rochford and No. 61 Squadron, see Foss’s list of “Cadets of Italian Detachment Posted Dec 3rd” in Foss, Papers.

13 See The National Archives (United Kingdom), Royal Air Force officers’ service records 1918–1919, record for Leo McCarthy, and McCarthy, R.F.C. Training Transfer Card.

14 McCarthy, undated letter to his father.

15 See McCarthy’s R.A.F. service record and his R.F.C. Training Transfer Card.

16 Deetjen, diary entry for January 27, 1918.

17 See McCarthy’s R.A.F. service record and his R.F.C. Training Transfer Card.

18 McCarthy, R.F.C. Training Transfer Card.

19 Quotations are from Deetjen’s diary entry for March 12, 1918.

20 See relevant entries in Clements’s and Foss’s diaries.

21 McCarthy, undated letter. A reference to the recent opening of the German Spring Offensive in this letter suggests it was written about March 25, 1918; a reference to the solo flying having occurred on Wednesday suggests it took place March 20, 1918.

22 The last named I assume is what is meant by “AW90″ on the card, i.e., an A.W. FK.3 with a 90 h.p. engine.

23 Cablegram 874-S.

24 Cablegram 726-S.

25 Cablegram 955-R.

26 McAndrew, “Special Orders No. 205.” See also McAndrew, “Special Orders No. 147,“ dated May 27, 1918.

27 McCarthy, letter to his father dated April 5, 1918.

28 McCarthy, letter of April 5, 1918.

29 “8th Aero Squadron,” p. 143; see also rosters on p. 132 and 136. (D.H.4 is a standard designation for the British plane, D.H.-4 for the American version.)

30 “8th Aero Squadron,” p. 112.

31 Sloan, Wings of Honor, p. 360.

32 “Praise for Rockland Boys by Col Edward L. Logan.” ” I have not thus far found his name on a manifest of a returning ship.

33 “Leo McCarthy, 73: Shoe Company President.”