(Troy, New York, July 21, 1893 – Rochester, New York, March 9, 1965).1

Desson’s paternal grandparents had emigrated from Prussia; his mother was born in Baden and had come to the U.S. in about 1866.2 Desson’s father was a farmer in Brunswick, New York, before moving to Troy, where he owned a grocery store.3 Desson attended Troy Academy, a college preparatory school, and then in 1915 entered Cornell to study veterinary medicine.4

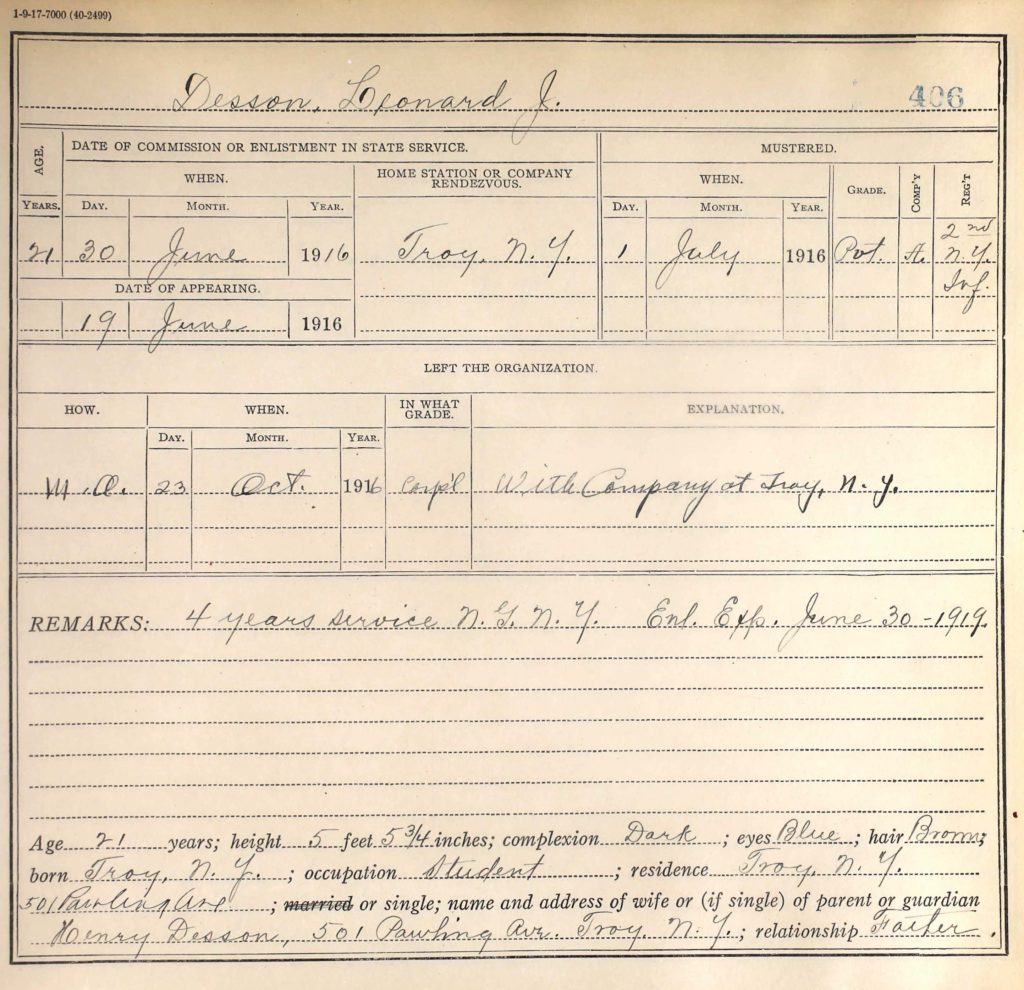

His name is on the New York National Guard muster rolls for the Mexican Punitive Campaign of 1916–17; as a member of the Second Infantry he would presumably have served under General Pershing on the Mexican border in the summer of 1916.5 When he registered for the draft in June 1917, he was in R.O.T.C. at Madison Barracks in New York. On the form he noted that he had served four years in the infantry and had the rank of corporal. He married Mary Ethel Harkness in Ithaca, New York, just before graduating from Cornell ground school on September 1, 1917.6

Desson, along with most of his ground school class mates, chose or was chosen to continue training in Italy, so he became one of the 150 men of the “Italian” or “second Oxford detachment” who sailed to England on the Carmania. They left New York for Halifax on September 18, 1917, and departed Halifax as part of a convoy for the Atlantic crossing on September 21, 1917. When the Carmania docked at Liverpool on October 2, 1917, the men learned that they were not to proceed to Italy, but to remain in England, where they would attend ground school (again) at the Royal Flying Corps’s No. 2 School of Military Aeronautics at Oxford University. After a month of this, most of the detachment, including Desson, travelled to Harrowby Camp near Grantham in Lincolnshire to attend machine gun school. He initially trained with a group that included Joseph Kirkbride Milnor, who kept a photo of the group.

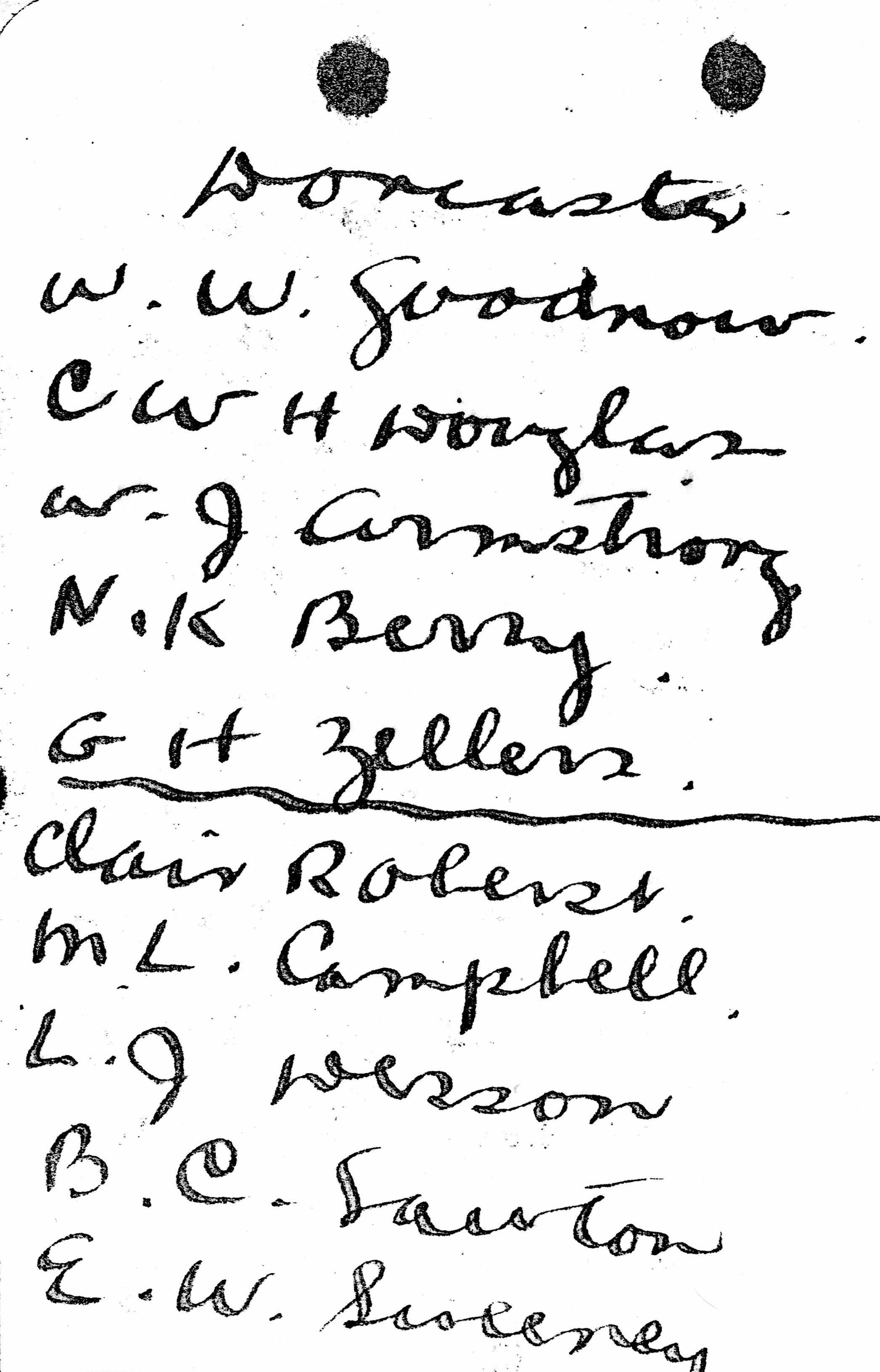

In mid-November, fifty of the Grantham men, including Desson, were selected to go on to flying schools. On November 19, 1917, he, along with his ground school classmate Weston Whitney Goodnow, as well as William Joseph Armstrong, Norman Kenneth Berry, Murton Llewellyn Campbell, Charles William Harold Douglass, Bradley Cleaver Lawton, Clair Rutherford Oberst, Earl William Sweeney, and George Herbert Zellers, set off for Doncaster in south Yorkshire where Nos. 41 and 49 Reserve [Training] Squadrons were located. Desson was assigned to No. 49 Training Squadron and roomed in Doncaster with Lawton and Murton Campbell; they trained on Maurice Farman Shorthorns.7 Soon after Christmas, Desson went to South Carlton and No. 45 T.S., a “pool squadron,” where men awaited assignment. His R.A.F. service record notes that on December 27, 1917 he was “for disposal.” There is a photo in John Chadbourn Rorison’s album of Desson standing next to a Sopwith Pup at No. 3 T.S. at Shoreham-by-Sea in the first part of the year, and this suggests that this was Desson’s assignment after Doncaster.8 At the end of January 1918 he went back to South Carlton, to No. 61 T.S.; there are some engaging photos of him there taken by fellow second Oxford detachment member Joseph Kirkbride Milnor.9 A recommendation that he be commissioned as a first lieutenant was forwarded by Pershing to Washington on March 19, 1918; the cablegram confirming the appointment is dated April 2, 1918.10

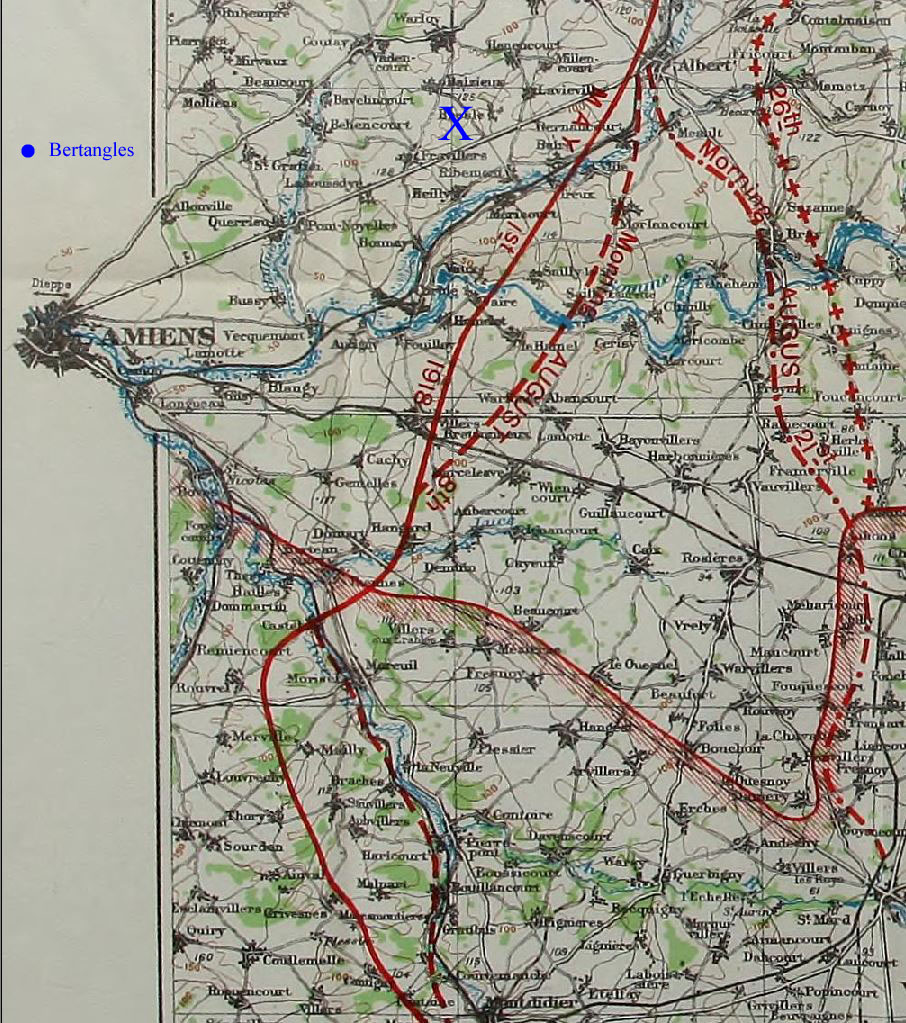

I have found no record of Desson’s advanced training, but he had evidently completed it by May 11, 1918. On that day he was posted to the R.A.F. and apparently attached to 2 A.S.D. in France; he was probably at the associated pilots pool, awaiting assignment to a squadron.11 On May 16, 1918, he was posted to No. 209 Squadron R.A.F., a Camel squadron stationed at Bertangles, a few miles north of Amiens—which city, as a result of the first phase of the German Spring Offensive, was now only about ten miles from the front.12

For a week Desson made practice flights and acquainted himself with the squadron, its planes, and the geography.12a The morning of May 19, 1918, he spent forty minutes practicing firing at a target and late in the afternoon took off in Camel D3373, “learning country.” Having gotten lost, he made a forced landing at Namps au Mont southwest of Amiens. He was evidently able to communicate his plight to the squadron and flew back to the aerodrome the next afternoon.

On May 23, 1918, Desson’s introductory period was over. Early that morning, flying D3328, he took part in a three-plane special mission; the other pilots were Robert Mordaunt Foster and Douglas Young Hunter. They attacked an enemy aircraft “over Boiselle”—presumably Ovillers-la-Boisselle, about two miles northeast of Albert and just inside the enemy lines—“E.A. was observed to flatten out and retire E[ast].” This was the first of many “W.E.A.” missions that Desson flew.12b These involved going after enemy observation aircraft near the lines whose wireless signals had been intercepted and used to determine their location. Cedric Nevill Jones, a 209 Squadron pilot, described missions of this type as “dashes after Hun two-seat artillery observation machines. Three of our aircraft were always on standby for these jobs . . . a Klaxon was sounded . . . and the standby pilots raced to their machines [and were] off the ground in two minutes after calling at the office for the chit with the location of the enemy aircraft.”12c

Poor weather the next three days meant little aerial activity on either side, but Desson was no doubt kept well occupied welcoming three fellow second Oxford detachment members assigned to 209 at this time: William Joseph Armstrong, Frank Aloysius Dixon, and Bradley Cleaver Lawton.12d

Desson next flew on May 27, 1918; he went out with Foster on a two-plane W.E.A. interception mission. His plane that day was Camel B6398, the plane he would continue to fly well into June. The next day he was flying at 4 a.m. as part of a four-plane formation charged with intercepting enemy bombers (the other pilots were Foster, Hunter, and Wilfred Reid May); they engaged a two-seater over Villers-Bretonneux, a few miles due east of Amiens, and drove it eastwards. Desson flew two further missions on May 28, 1918; he returned early from a W.E.A. with Foster and Hunter, having lost the “formation in low clouds at 4,000 ft.,” but gamely set out again with May and William John MacKenzie for an hour and a half flight in the late afternoon.

Desson continued flying W.E.A. missions almost daily through June 5, 1918. On that day, after returning from one such mission in the morning, he was sent out again in the early evening in company with Hunter, Foster, John Henry Siddall, Cedric George Edwards, and Leslie Campbell Story on his first high offensive patrol. After forty-five minutes of flying, at 7:10 p.m., they engaged four Pfalz scouts over Laboissière-en-Santerre with indecisive results, and, thirty-five minutes later drove away east an enemy two-seater observed over Davenescourt. The mission lasted two hours.

The next day Desson, along with Foster, May, Hunter, and James Andrew Fenton, set out to intercept enemy aircraft near Dernancourt just south of Albert. Whether it was their original target or not is unclear, but they attacked a Rumpler C (a two-seat observation plane) east of Villers-Bretonneux at 8:30 p.m. and forced it to land in Allied territory, about seven miles to the north, between Bresle and Ribemont sur l’Ancre.12e Foster (flying B3858) and Desson apparently put in a claim for this plane, but it was “not credited.”12f

On June 9, 1918, the German army opened the fourth of its 1918 offensives, an operation variously known as Gneisenau, the Battle of the Matz, and Montdidier-Noyon. An unusually large formation of eleven planes from 209 set off in the late morning to assist in the defense, flying in the area Desson knew slightly from his high offensive patrol four days previously.12g This time flying D3329, Desson (as well as Lawton and Armstrong) participated in the mission. The planes carried bombs and dropped them between Boussicourt and Davenescourt and also east of Montdidier. At 12:50 Desson attacked an enemy plane and then lost the formation; he returned to Bertangles about half an hour ahead of most of the other planes. The squadron record book notes a “two-seater driven down out of control between Pozières and Contalmaison”—some twenty miles east northeast of Bertangles, indicating that the formation did not take the direct path back to the aerodrome. With the documents to hand, I cannot tell whether the plane driven down out of control was the one Desson attacked. I find no record of a claim having been made, but that may again reflect lack of access to the appropriate documents.

Desson next flew a mission on June 12, 1918, yet another W.E.A. interception. Despite having tested the engine of Camel B6398 the preceding day, he had trouble with it and returned early. That evening, on a special patrol with Foster and Ralph Daniel Gracie, he flew D3420, which remained his plane for the rest of his time with 209. Around this time nearly half of the squadron succumbed to influenza, but Desson was evidently not affected and continued to fly. From June 13 to June 24, 1918, inclusive, he flew five W.E.A. missions and one low offensive patrol. On three of the W.E.A. missions (June 15 and 17, 1918), his only companion was Hunter, reflecting the squadron’s lack of manpower during this period. On June 24, 1918, during his last flight with 209, another W.E.A. interception, he, Hunter, and Merrill Samuel Taylor attacked a two-seater at 9:30 a.m. and drove it down east from Marcelcave.

Soon after this flight, Desson, along with Armstrong, Lawton, and Dixon, was ordered to join the U.S. 17th Aero Squadron (also flying Camels) at Petite Synthe on the coast near Dunkirk, about seventy miles north of Bertangles. Arriving on or about June 26, 1918, they joined a number of other members of the second Oxford detachment already assigned there.13 The 17th flew Camels and, along with the 148th, was American in personnel, but stationed on the British Front and under the tactical command of the R.A.F. until very late in the war when they were moved south to the American Front. Desson was in A flight, under flight commander Goodnow and deputy commander Murton Campbell.14

After about three weeks of getting to know their equipment and their territory while working on formation flying (and crossing the lines, despite R.A.F. regulations), the 17th flew their first offensive patrol on July 15, 1918. They began escorting DH.9 bombers into German occupied territory on July 20, 1918.15 On July 30, 1918, Desson was hospitalized at Queen Alexandra Hospital in Dunkirk for several days, perhaps for influenza; when he returned to the squadron he learned that his roommate, Murray Kenneth Spidle, had gone missing from a patrol on August 4, 1918, and before long Desson took up the task of disposing of Spidle’s belongings and writing his parents.16

In August 1918 plans for an attack on the large enemy aerodrome at Varsenare were being matured, and the 17th Aero, in cooperation with several R.A.F. squadrons, executed a successful bombing raid there on August 13, 1918. In his report of the raid, squadron historian Frederick Mortimer Clapp says of Desson: “Dropped four bombs on château [the aerodrome headquarters building] from about 300 feet and fired into windows; was compelled to climb as air pressure was dead and had to depend on gravity and hand pump”; despite a partially disabled plane, Desson, along with all the other raid participants, made it back to base.17

A few days later, on August 17, 1918, the 17th moved south from Petite Synthe to Auxi-le-Château northwest of Doullens; they were again to escort R.A.F. bombers, but also to do their own bombing and strafing.18 Desson’s name does not appear in the bombing raid reports for August after the Varsenare raid, and, in any case, the squadron was given a quiet spell after losing a large number of men on August 23, 24, and 26, 1918.19 On September 12, 1918, he took part in the first patrol over enemy lines after this period of quiet, helping to chase an enemy two-seater (presumably a reconnaissance plane) away from Cambrai.20

On September 20, 1918, the 17th Aero moved once again, this time to Soncamp Aerodrome, about fifteen miles east of Auxi-le-Château, and patrols, including one by A flight, to which Desson belonged, began that day.21 Desson took part in an offensive patrol on September 24, 1918, in the vicinity of Cambrai which engaged a large number of Fokkers; he filed a combat report for a “Fokker biplane driven down.” It was apparently still under control at last sighting, and Desson, preoccupied with the other enemy planes, could not observe the results.22 Desson subsequently participated in at least ten bombing raids in the vicinity of Cambrai between September 27 and October 14, 1918, the targets moving farther to the east as the drive to take Cambrai progressed and succeeded.23

On September 20, 1918, the 17th Aero moved once again, this time to Soncamp Aerodrome, about fifteen miles east of Auxi-le-Château, and patrols, including one by A flight, to which Desson belonged, began that day.21 Desson took part in an offensive patrol on September 24, 1918, in the vicinity of Cambrai which engaged a large number of Fokkers; he filed a combat report for a “Fokker biplane driven down.” It was apparently still under control at last sighting, and Desson, preoccupied with the other enemy planes, could not observe the results.22 Desson subsequently participated in at least ten bombing raids in the vicinity of Cambrai between September 27 and October 14, 1918, the targets moving farther to the east as the drive to take Cambrai progressed and succeeded.23

About ten days later, word was received that the 17th was to move to the American sector.24 On November 1, 1918, they began the train journey south, arriving, finally, near Toul on November 4, 1918.25 Plans for the men of the 17th to fly for the A.E.F. came to naught in the jubilation of the armistice. Soon thereafter, various group photos of the squadron were taken. About November 25, 1918, Goodnow, George Augustus Vaughn and Desson, “three fellows who had been at the front the longest,” were ordered to report to Issoudun; “the orders did not say so, but we understood that we were to be sent home as soon as possible.”26 At some point they separated, sailing home on different liners. Desson, joined now by fellow second Oxford detachment members Oberst and Conrad Henry Matthiessen, boarded the U.S.S. Finland at St. Nazaire on January 31, 1919, and arrived back in New York on February 14, 1919.27

He returned to Cornell to resume his studies and was awarded a degree in veterinary medicine. He had a veterinary practice and kennels in Pittsford, a suburb of Rochester, New York.28

mrsmcq June 16, 2017

Updated February 25, 2019, to reflect 209 Squadron record book

Notes

(For complete bibliographic entries, please consult the list of works and web pages cited.)

1 For Desson’s place and date of birth, see Ancestry.com, U.S., World War I Draft Registration Cards, 1917-1918, record for Leonard J Desson. His place and date of death are taken from “Necrology,” in Cornell Alumni News, p. 71. The photo is taken from p. 117 of The Cornellian and Class Book: The Yearbook of Cornell University, 1918.

2 Ancestry.com and The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, 1880 United States Federal Census, records for Henry and Louise Deson [sic].

3 See the 1880 census record cited above, and Ancestry.com, 1910 United States Federal Census, record for Henry T Desson.

4 Cornell University, Cornell Alumni Directory, p. 84; The Cornellian and Class Book: The Yearbook of Cornell Univesity, 1918, p. 117.

5 Ancestry.com, New York, Mexican Punitive Campaign Muster Rolls for National Guard, 1916-1917, record for Leonard J Desson.

6 “Trojan Marries at Ithaca”; “Ground School Graduations [for September 1, 1917].”

7 See Foss, Diary, entry for November 15, 1917; The National Archives (United Kingdom), Royal Air Force officers’ service records 1918-1919, record for L. J. Desson; and Murton Campbell, Diary, entry for November 19, 1917 et seq.

8 Doyle, “War Birds Pictorial,” p. 36

9 The National Archives (United Kingdom), Royal Air Force officers’ service records 1918-1919, record for L. J. Desson.

10 Cablegrams 750-S and 1028-R.

11 See Munsell, “Air Service History,” p. 194 (9), and “Lieut. Leonard Joseph Desson USAS.” On the location of 2 Aeroplane Supply Depot, see Dye, The Bridge to Airpower, p. 179. By the end of May the pilots pool associated with 2 A.S.D. was established at Rang-du-Fliers (see Deetjen’s diary entry for May 30, 1918), but it is an open question whether it was already there on May 11, 1918. I should note that the caption on p. 43 to photo 40 in Doyle, “War Birds Pictorial” of a group of men at Rang-du-Fliers between June 8 and June 14, 1918, identifies one of the men as Desson; the identification must be in error (although the other identifications appear to be accurate).

12 On his assignment to 209, see “Lieut. Leonard Joseph Desson USAS.”

12a Here and in the subsequent description of Desson’s period with No. 209, information is taken from No. 209 Squadron Record Book (RFC/RAF).

12b W.E.A. is apparently not a widely used abbreviation; it probably stands for “wireless enemy aircraft.” See “RAF abbreviation ‘W.E.A.’—special mission intercepting.”

12c C. N. Jones, “As I Remember,” p. 38. On wireless interception see also Balfour, An Airman Marches, p. 127.

12d See the R.A.F. casualty forms for Dixon (“Lieut. F A Dixon USAS”) and Lawton (“Lieut. Bradley Cleaver Lawton USAS”), as well as Munsell, “Air Service History,” p. 192 (7) for Armstrong, p. 194 (9) for Dixon, and p. 197 (12) for Lawton.

12e No. 209 Squadron Record Book (RFC/RAF) provides the map coordinates “D21b. Sheet 62d” for where the enemy plane was forced to land. Digital versions of Sheet 62d are available at the World War I map collection web site of McMaster University Library and the British First World War trench maps web site at the National Library of Scotland. P. 437 of H. A. Jones, The War in the Air, vol. 6, is a map that shows, i.a., the lines near Amiens as of May 1, 1918.

12f See the entry for Desson’s plane (B6398) in Sturtivant and Page, The Camel File.

12g The squadron record book inadvertently has the formation setting out at 11:25 p.m. rather than a.m.

13 Clapp, A History of the 17th Aero Squadron, p. 156, has all four men assigned as pilots to the 17th on June 26, 1918. Munsell, “Air Service History,” p. 194 (9), gives June 25, 1918 as the date of assignment for Desson and Dixon; but for Armstrong, p. 192 (7), and Lawton, p. 197 (12), June 26, 1918.

14 Reed and Roland, Camel Drivers, p. 27

15 See Clapp, A History of the 17th Aero Squadron, p. 24; Reed and Roland, Camel Drivers, pp. 35 and 40.

16 Clapp, A History of the 17th Aero Squadron, p. 156; Reed and Roland, Camel Drivers, pp. 41 & 46. Desson’s letter to Spidle’s parents (cited in part in Camel Drivers, p. 47) was apparently published in the Massillon, Ohio, Evening Independent on September 3, 1918 (“From Independent Files: 25 Years Ago”).

17 Clapp, A History of the 17th Aero Squadron, p. 98; see also Reed and Roland, Camel Drivers, pp. 59-60.

18 See Murton Campbell, diary entry for August 17, 1918, for the date of the move, which is unclear in other sources ( Clapp A History of the 17th Aero Squadron, p. 37; Reed and Roland, Camel Drivers, p. 64).

19 I am puzzled by the absence of his name in records of the raids of August 23-26, 1918, given that the squadron seemed to be using every pilot who was fit.

20 Reed and Roland, Camel Drivers, p. 92.

21 Reed and Roland, Camel Drivers, p. 98.

22 Clapp, A History of the 17th Aero Squadron, p. 84.

23 Clapp, A History of the 17th Aero Squadron, pp. 106-45.

24 Read and Roland, Camel Drivers, Chapter 10, note 34, cite a communication presumably from James Guthrie Harbord dated October 25, 1918, regarding the change of command.

25 See Read and Roland, Camel Drivers, pp. 115–20, and Clements, diary entries for October 28–November 4, 1918, on the move to the American sector.

26 Vaughn, War Flying in France, letter of November 28, 1918. Vaughn does not identify the three, but Clements, in his (combined) diary entry for November 13–25, 1918, provides the names.

27 War Department, Office of the Quartermaster General, Army Transport Service, Lists of Incoming Passengers, 1917 – 1938, Passenger list for Casual Officers Detachment, on Finland.

28 “Necrology” in Cornell Alumni News, p. 71.