(Elizabeth, New Jersey, October 16, 1897 [?] – Eggertsville, New York, May 19, 1964).1

No. 112 Squadron, 5 T.D.S. Stamford ✯ 9 T.S. Sedgeford ✯ France

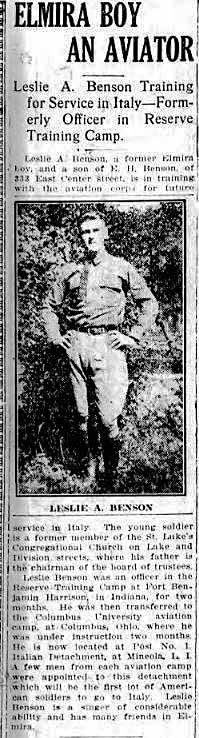

Benson’s mother, Louisa Elizabeth Hawkins, emigrated with her family from Staffordshire, England, to New Jersey around 1882.2 There she met and married Ernest Herman Benson, who was working in Elizabeth as an erecting engineer.3 They had two children, both boys; Leslie A.A. Benson was the younger. By 1910, the family had moved to Elmira, New York, where Ernest Herman Benson was employed by the American Bridge Company.4 Leslie A. A. Benson attended the Elmira Free Academy, where he excelled in football and drama and became known as a fine bass-baritone.5 After graduating in 1916, he entered Ohio University in Athens, Ohio, with the class of 1920.6 In the spring of 1917, he was accepted as a candidate for R.O.T.C. at Fort Benjamin Harrison in Indiana. Benson evidently applied to and was accepted by the Aviation Section of the Signal Corps, because in the summer of 1917 he entered ground school at the School of Military Aeronautics at Ohio State University, graduating on September 1, 1917.7

Along with most of his O.S.U. classmates, Benson chose or was chosen to train in Italy, and he joined the 150 men of the “Italian” or “second Oxford detachment” who sailed to England on the Carmania.8 They departed New York for Halifax on September 18, 1917, and departed Halifax as part of a convoy for the Atlantic crossing on September 21, 1917. The men of the detachment, travelling first class, had plenty of leisure, apart from submarine duty towards the end of the voyage and daily Italian lessons conducted by Fiorello La Guardia, who was travelling with them. It was thus a surprise when, on docking at Liverpool on October 2, 1917, the members of the “Italian detachment” learned that they would not continue to Italy, but would remain in England and attend ground school (again) at the Royal Flying Corps’s No. 2 School of Military Aeronautics at Oxford. There was some grumbling, but the men fairly quickly settled in to life at Oxford. Since their work at Oxford was in part a repetition of what they had already learned in the U.S., the cadets did not need to work as hard as they might have, and they had considerable leisure for exploring the town and the surrounding countryside and engaging in various athletic and social activities.

On November 3, 1917, twenty men were able to go to Stamford to begin flight training, but nearly all the others, including Benson, departed that day for Grantham in Lincolnshire to attend gunnery school at Harrowby Camp. As Parr Hooper, also ordered to Grantham, remarked, “It looks like we got sent here because there was no other place to send us to—playing for time.”9 John McGavock Grider, who roomed with Benson, described their status at Grantham: “We rank as officers and don’t have to salute any thing under Majors and on the other hand we are not officers and are not saluted by privates.”10 Eight men were assigned to a hut, and, initially, in addition to Grider, Benson shared with Thomas John Herbert and Clarence Horn Fry, who had been at O.S.U., as well as Laurence Kingsley Callahan, Finley Austin Morrison, Joseph Raymond Payden, and John Howard Raftery.11 In mid-November, after places opened up for fifty men at training squadrons, five of these men left to begin flight training; Benson, Payden, and Raftery were among those who remained at Grantham to complete a second machine gun course—the first had been on the Vickers gun; the cadets now learned about and practiced with the Lewis.

No. 112 Squadron, 5 T.D.S. Stamford

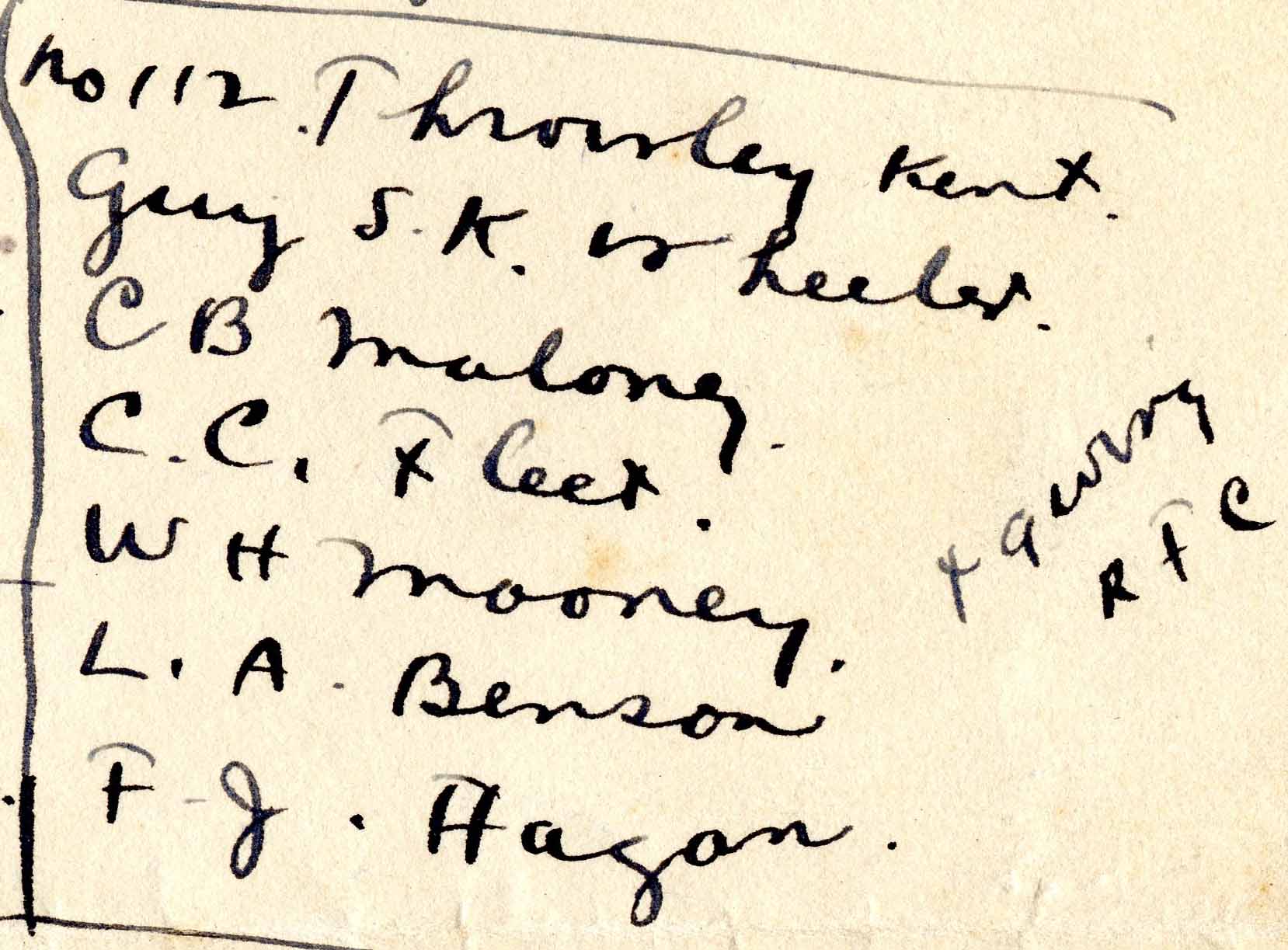

On December 3, 1917, the remaining men at Grantham were finally posted to squadrons. According to a list drawn up by Fremont Cutler Foss, Benson was assigned to No. 112 Squadron, a home defense squadron at Throwley in Kent, along with Charles Carvel Fleet, Francis Joseph Hagan, Clarence Bernard Maloney, William Henley Mooney, and Guy Samuel King Wheeler.12 All of these men had, as it happens, been at ground school at O.S.U., although Fleet, Maloney, and Wheeler had been one class ahead of the others.

No. 112 flew Camels, which, of course, could not be used for primary instruction. There must also, however, have been some two seaters; Fleet wrote to Parr Hooper from Throwley that he and the other cadets were “billeted in nice homes and do not do anything except occasional flying when the pilots feel like taking them up.”13

Indirect evidence indicates that Benson, along with the other five American cadets at No. 112, was reposted on January 26, 1918, and that he, Fleet, Maloney, and Mooney were assigned that day to No. 5 Training Depot Squadron at Easton on the Hill, a couple of miles southwest of Stamford (the second Oxford detachment members sent to Stamford in early November had been assigned to No. 1 T.D.S. about three miles to the east, near Wittering).14 Around the middle of February 1918, Hagan, who had been posted to Boscombe Down near Amesbury in Wiltshire, wrote to Benson at 5 T.D.S., opining enviously that “You should by this time have completed your 20 hours solo and have your wings up.”15 In fact, it appears that Benson was even more frustrated than Hagan, as the first flight recorded in his log book did not take place until March 4, 1918.16

Bad weather cannot account for Benson’s not flying during February, as the log books of second Oxford detachment members Pryor Richardson Perkins and John Warren Leach, also at No. 5 T.D.S. at this time, show them flying during this period. However, Perkins and Leach had been assigned to 2 flight, while Benson was in 4 flight. Robert Thomas Palmer was also in 4 flight at 5 T.D.S. during this period, and his log book is similarly blank in February 1918; it seems likely that 4 flight, in contrast to 2, had insufficient planes and/or instructors.

Finally, on March 4, 1918, Benson began his training. Instructor Harry Kent Capper took him up as a passenger for ten minutes in a B.E.2e ([B?]9993), an operational aircraft by now obsolete and mainly used for training.17 The same day, Roger Bark Corfield, 4 flight’s O.C., took him up twice more in the same plane and then once in a DH.6 ([C]2028), a plane designed for training, apparently to demonstrate landings.18

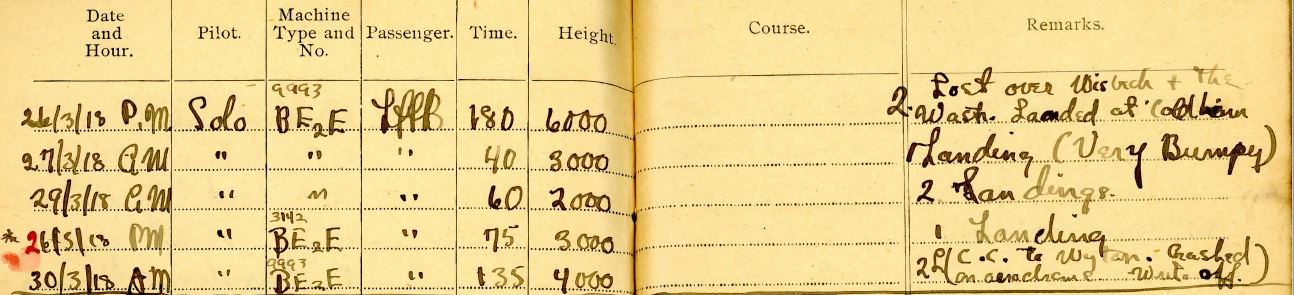

Over the next week and a half, Benson was able to fly most days. On March 22, 1918, after instructor Alan Carnegy Horsbrugh had tested him “for solo,” Benson flew B.E.2e 9993 solo for fifty minutes. Just two days later he flew the same plane for over an hour, some of the time at 8,000 feet, thus completing his altitude test, one of the prerequisites for graduation from this stage of R.F.C. training. On March 26, 1918, still in 9993, he flew for three hours; in his log book he wrote “Lost over Wisbech & the Wash. Landed at Coldham.” A few days later, he tried to complete another graduation prerequisite, a cross-country flight. He flew to Wyton about twenty-five miles to the southeast of Easton on the Hill and Stamford, but crashed “on aerodrome”—presumably at Easton on his return. Plane 9993 was a “write-off,” but Benson himself evidently escaped injury from this, his only recorded crash.

Nothing daunted, Benson went up solo again in another B.E.2e on April 2, 1918—the day after the R.F.C. became the R.A.F.—and soon made two more cross-country flights, the first on April 4, 1918, when he flew up to Grantham and back, taking photos, and then on April 8, 1918, with a Lt. Hall as his passenger, when he flew to Narborough and back to Easton. He now had flown over seven hours dual and over twenty-one hours solo and had thus fulfilled yet another graduation requirement (originally “20 hours solo in the air,” changed at some point to “25 hours in the air solo and dual combined”19).

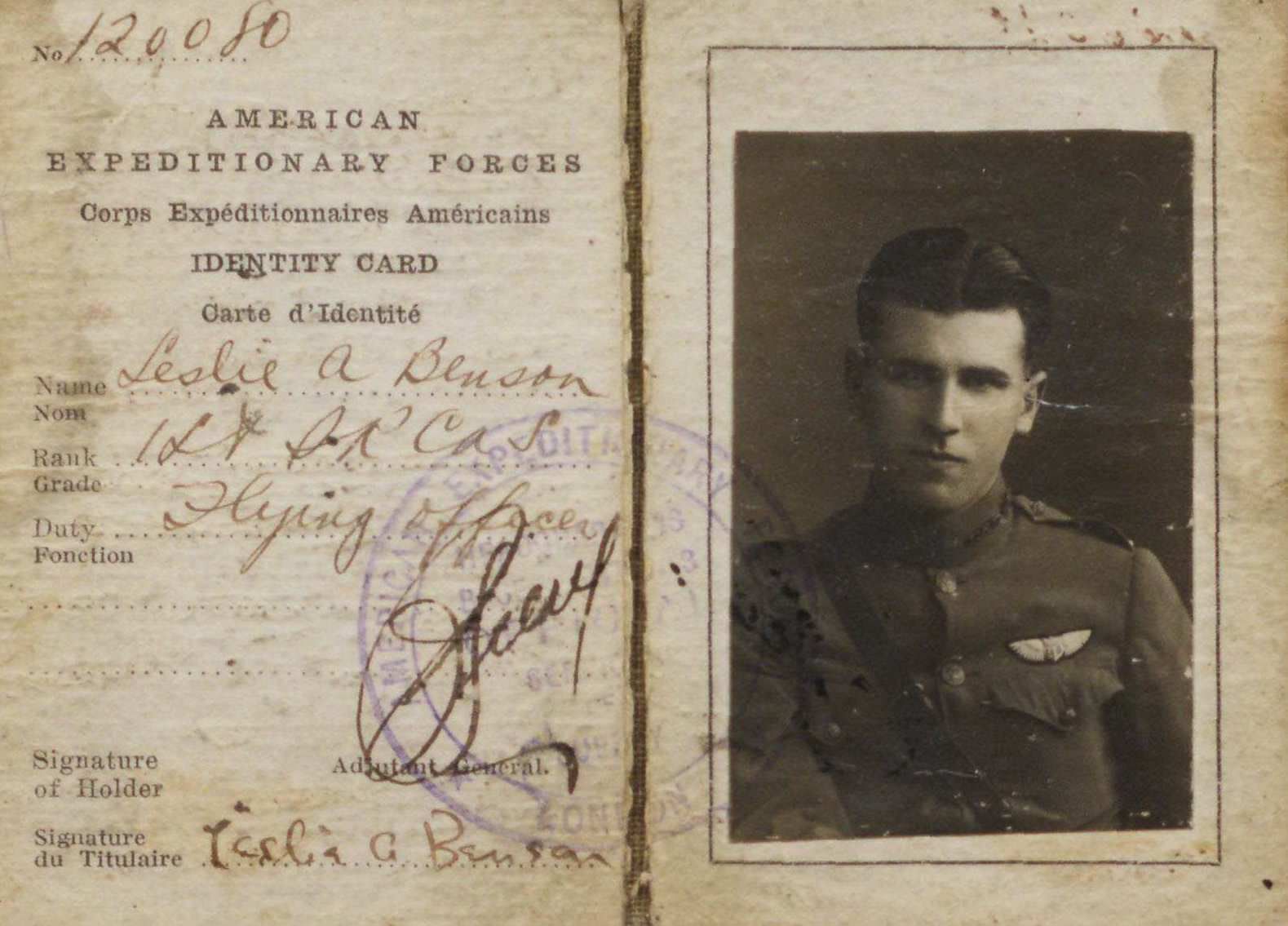

On this same day, April 8, 1918, Pershing cabled the War Department, recommending that Benson, along with many others, be commissioned a first lieutenant.20 It had been brought to Pershing’s attention that many aviation cadets had come to Europe expecting to begin flight training immediately but had instead kicked up their heels for months. As Pershing wrote in a cablegram dated March 13, 1918, “All of those cadets would have been commissioned prior to this date if training facilities could have been provided. These conditions have produced profound discouragement among cadets.”21 To remedy this injustice, and to put the European cadets on an equal footing with their counterparts in the U.S., Pershing asked permission “to immediately issue to all cadets now in Europe temporary or Reserve commissions in Aviation Section Signal Corps. . . .”22 Washington approved the plan in a cablegram dated March 21, 1918, but stipulated that the commissioned men be “put on non-flying status. Upon satisfactory completion of flying training they can be transferred as flying officers.”23 And, indeed, Pershing’s April 8, 1918, cablegram recommended that Benson and a number of others be commissioned as “First Lieutenants Aviation Reserve non-flying.”

On April 20, 1918, Benson was finally able to go up in a service plane, an R.E.8, but only as Corfield’s passenger. Four days later, however, after having been tested for solo flying in an R.E.8, he went up in the same plane as a pilot, thus fulfilling the last R.F.C. / R.A.F. graduation requirement. It was perhaps in part to celebrate this accomplishment that over the next day or so he took Fleet and Maloney, and perhaps also Mooney and Hagan (if I read the name correctly; Hagan must have been visiting) up as passengers with him in a B.E.2d.24 By the time Benson finished at 5 T.D.S. on May 9, 1918, he had nearly fifty-six hours of flying time under his belt, most of it solo.

9 T.S. Sedgeford

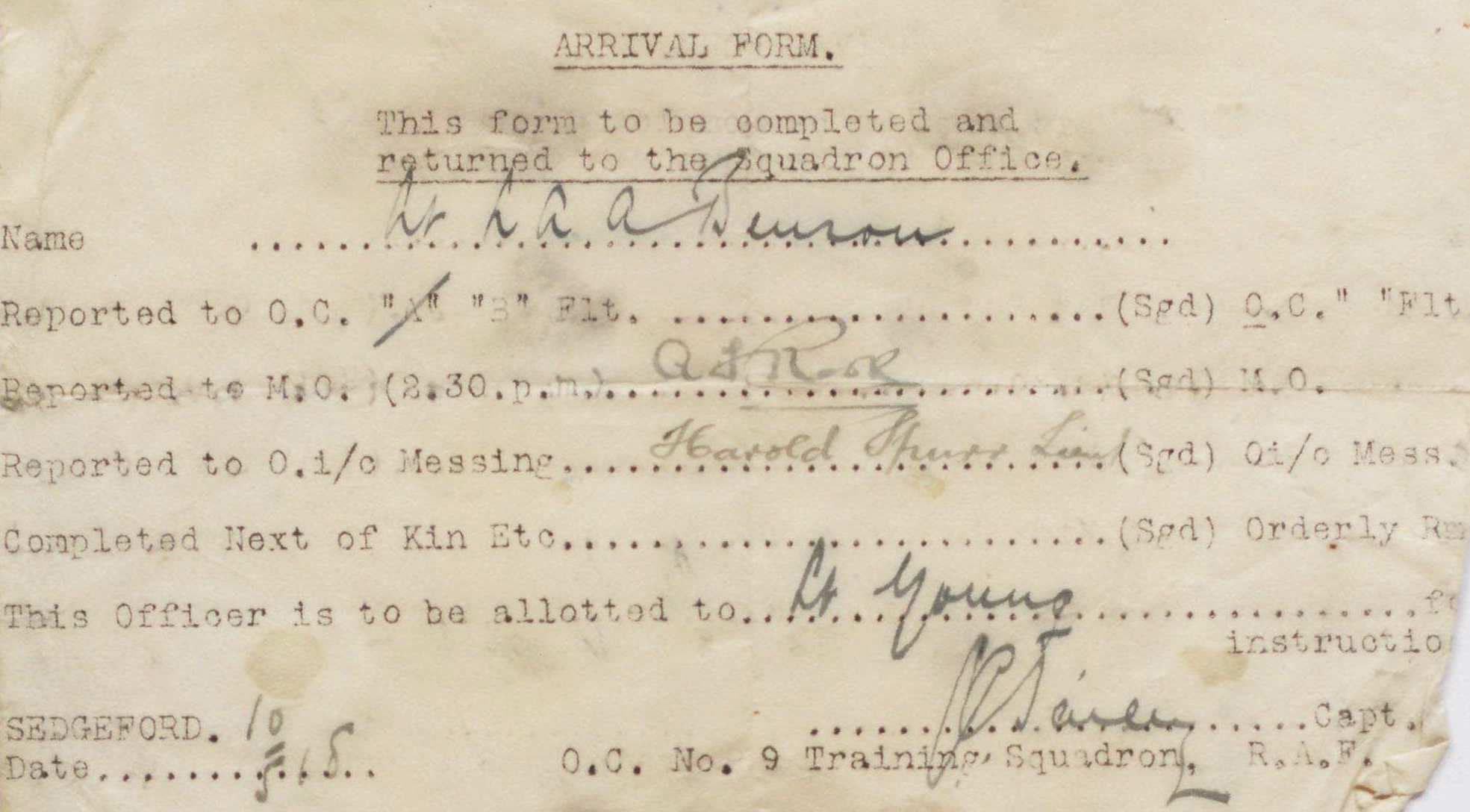

May 10, 1918, finds Benson reporting to B flight of No. 9 Training Squadron at Sedgeford in Norfolk.25

Harold Ernest Goettler, also at Sedgeford, noted in his diary that day that “[I] met an American tonight at supper by the name of Benson—he is a Beta [fraternity member] and was just posted to our Squadron.” Benson’s commission was (finally) confirmed in a cable dated May 13, 1918; news of the consequent celebration spread, and Fleet, just departing for Wyton, commented on it.26

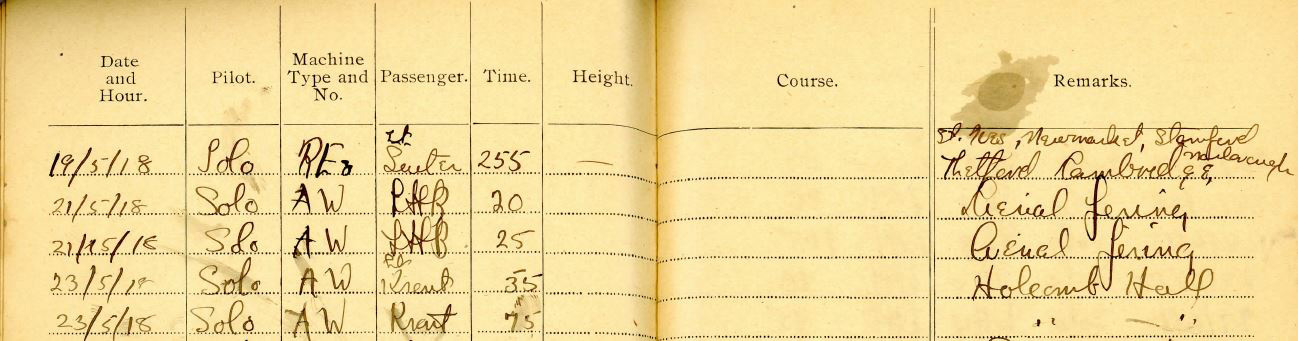

Benson trained at Sedgeford from May 10, 1918, through mid-July 1918. He initially put in a great deal of time flying R.E.8s, although he was taken up briefly as a passenger during his first week in an DH.4 and in an “AW” (presumably an Armstrong Whitworth FK.3). At the end of the month he again made flights as a passenger in a DH.4; it may well be that a couple of times his pilot (“Bird”) was second Oxford detachment member Allen Tracy Bird, who had been at No. 9 T.S. since April 1918. Finally, on June 11, 1918, Benson was able to take a DH.4 up solo and over the next few days got in several hours as a pilot on this plane.

On June 19, 1918, Benson was back flying an R.E.8. On this day he and passenger Suiter (probably Wilber Carleton Suiter of the second Oxford detachment) made a tour lasting over four hours—close to the limit of the R.E.8’s endurance if they did not refuel—taking in Cambridge, over fifty miles to the southwest of Sedgeford, and Narborough, over seventy-five miles to the west of Sedgeford; it is unclear from the log book entry what their precise flight path was.

Benson practiced aerial fighting in an A.W. on June 21, 1918, and then on June 23, 1918, flew to “Holcomb Hall,” i.e. to Holkham Hall, the grand country house of the Earl of Leicester just east of Sedgeford, returning later the same day. Benson’s passenger, “Lt. Kraut” (probably Ray Worrall Krout), had apparently visited Holkham Hall a few days previously as one of a party of Americans at Sedgeford who had been invited to tea by Lord Leicester.27 Perhaps Benson’s passenger had been able to acquire another invitation, this time for himself and Benson.

Benson continued to pile on the hours flying solo; by the end of June 1918 he calculated that he had over 120 hours of flying time, 106 of which were solo, mainly on R.E.8s and A.W.s, but including nearly eleven hours solo on DH.4s. On July 1, 1918, he flew as a passenger for the first time in a DH.9 ([D]5601), and three days later flew a DH.9 solo. During the first week of July 1918 he also took up as passengers in an A.W. Herbert Bryce-Smith—the officer who signed off on his log book at 9 T.S.—and Ralf Crookston, another second Oxford detachment member.

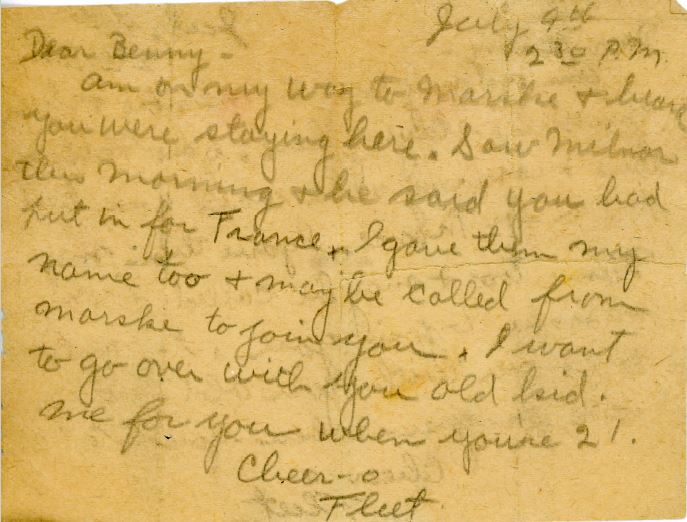

Benson records no flying from July 6 through July 12, 1918, and other documents, including a ration card, indicate he travelled to London and back during this period. His friend Fleet, on his way to a school of aerial fighting at Marske-by-the-Sea, left Benson a note dated July 9 [?], 1918: “heard you were staying here. Saw Milnor this morning & he said you had put in for France”—Joseph Kirkbride Milnor was working at American Aviation H.Q. in London. A receipt dated July 8, 1918, indicates that Benson had that day been issued flying clothes from stores of the (American) quartermaster in London.28

Benson was once again flying at Sedgeford on July 13 and 14, 1918. He closed out his training at there on July 14, 1918, when he flew an R.E.8 with passenger (Roy Underhill?) Dabbs; he had logged a total flying time of just over 146 hours, with just over 122 hours solo.

France

Like Fleet, most second Oxford detachment pilots at this point in their training spent at least a brief period at one of the schools of aerial fighting, at Marske or at Ayr and Turnberry, but Benson’s log book does not record any flying at these schools. Two weeks after finishing up at Sedgeford, he was in France.

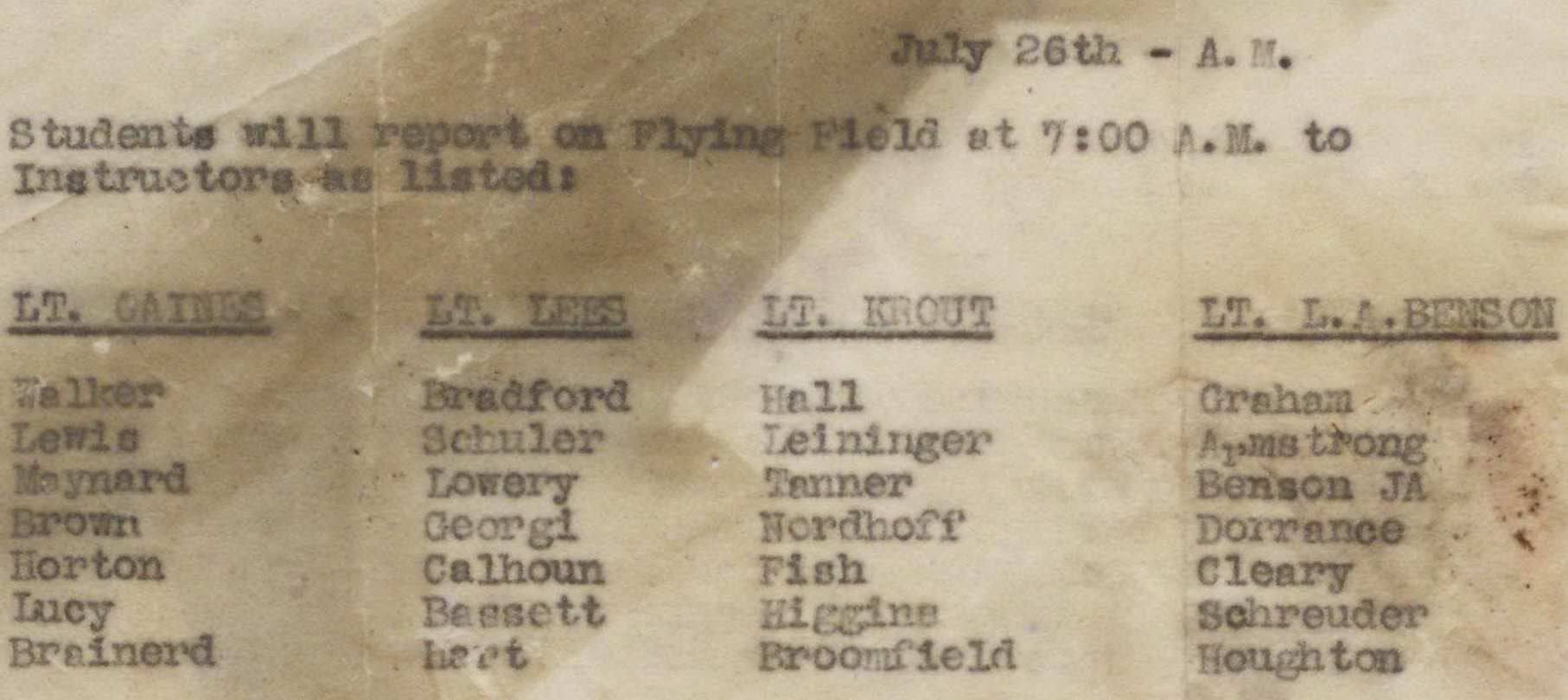

Benson apparently immediately began serving as an instructor. Among his papers is a list of students and instructors dated July 26 [1918]; it does not indicate where the instruction was taking place, but, in addition to himself and his quondam passenger Lt. Krout, one of the instructors was “Lt. Gaines,” probably Albert Belding Gaines, who taught at the Third Aviation Instruction Center at Issoudun.29

And, indeed, a memo from Geoffrey James Dwyer, who oversaw American pilots training in England, includes Benson, along with a number of other second Oxford detachment men, in a long list of men at the 3rd A.I.C. in July.30 Most were there to be trained on DH-4s; Benson had evidently distinguished himself already as a student sufficiently to be selected as an instructor. Hiram Bingham, in charge of the flying school at Issoudun, recalled that “With a sense of the importance of having the best possible teachers and a keen realization of the old adage that ‘a stream cannot rise higher than its source,’ it was early determined to retain only the very best American pilots for teachers and instructors.”31 Entries in Benson’s log book resume on July 26, 1918, indicating he was flying a “Liberty” DH-4—the American version of the British DH.4, equipped with a Liberty engine. Names of his passengers for this date correspond to those under his name in the list of instructors and pupils cited above.

The last entry in Benson’s log book is dated August 4, 1918, but a further list among his papers, dated August 6 [1918], shows him still involved in DH-4 instruction; another dated August 28, 1918, puts him at “HQ. Field No. 7,” presumably at Issoudun, continuing DH-4 instruction, and a memo from September 17, 1918, has him in charge of “spirals” and stipulates that students at Field No. 7 “reporting for formations and spirals will report to Lt. Benson for landings.” On September 20, 1918, with fellow second Oxford detachment member Harry Adam Schlotzhauer as pilot, he took a brief “joy ride” in a DH.9A.31a

The next day Benson received permission to take a week’s leave in Cannes.32 At some point after his return to Issoudun, he was reassigned to the recently opened Field No. 10 there. In the history of the field, written in late November 1918, Benson is among the staff “honorably mentioned in connection with the success at Field 10”; he is described as a “Testor of Students.”33 An article about Field 10 in the Plane News (the “Air Service Paper of the A.E.F.,” published at the 3rd A.I.C.) for February 8, 1919, thanks and lists the “Efficient Instructor Staff,” including “Leslie A. Benson.”34

There is some indication that Benson served briefly as an instructor at the Second Aviation Instruction Center at Tours.35 In any case, towards the end of the war, he was posted to a squadron, the American 258th Aero, which flew Salmson 2 A.2s. Benson’s notes in an Officer’s Record Book indicate that he joined the 258th in October 1918.36 The 258th had been for a time stationed at Luxeuil; when it finally became operational at the end of October 1918, it was flying out of Mathay Aerodrome in eastern France near the border with Switzerland, a good thirty miles southeast of Luxeuil. When the war ended, the 258th was in the process of relocating to an aerodrome near Manonville, ten miles north of Toul, to take part in operations against Metz.37

George Robert Holmes was posted to the 258th around the same time as Benson and served as Benson’s observer.38 The two of them remained with the squadron in France well into the spring.

In early May 1919, the 258th relocated to Weißenthurm on the left bank of the Rhine a few miles northwest of Coblenz, as part of the Army of Occupation.39 Holmes may by this time have left the squadron, as he is documented embarking at Bordeaux for the voyage home on May 12, 1919.40 Benson, however, apparently remained with the squadron into June, when he made his way via Paris to Le Havre.41 From there he was able to return home on the S.S. La Lorraine, which sailed on June 21, 1919, and arrived in New York on June 30, 1919.42

On returning to the U.S. Benson took up medical studies at the University of Buffalo and set up a medical and surgical practice in Buffalo, New York. 43

mrsmcq May 17, 2017; revised September 30, 2020; April 7, 2021; September 16, 2022, based on flying log book and Benson, miscellaneous papers and photos

Notes

(For complete bibliographic entries, please consult the list of works and web pages cited.)

1 Benson’s full name is taken from Ohio University, Catalog of Ohio University Athens, Ohio 1916-1917 and Circular of Information for 1917-1918, p. 215. Benson’s gravestone (see Boone, “Dr Leslie A A Benson”) indicates he was born in 1897, and his high school graduation and college entrance dates (see below) would support this date, as do census records and a New Jersey birth record (Ancestry.com, New Jersey, Births and Christenings Index, 1660–1931, record for Benson.) However, Benson’s draft registration, one of his New York military service cards, and an Officer’s Record Book give 1895 as his year of birth. See Ancestry.com, U.S., World War I Draft Registration Cards, 1917–1918, record for Leslie Alfred Benson, and Ancestry.com, New York, Abstracts of World War I Military Service, 1917–1919, record for Leslie Alfred Benson; the Officer’s Record Book is in Benson, Leslie A. A. Benson Collection, 1917-1919. Benson thus appears to be one of a number of men of the second Oxford detachment whose year of birth changed perhaps for military service purposes. For Benson’s date and place of death, see “Benson, Leslie A. A., MD.” The photo is a detail from a group photo of Squadron 8 at the Ohio State University School of Military Aeronautics; Benson stands at the far left.

2 This information is based on documents related to Louisa Elizabeth Hawkins (1870–1926) available at Ancestry.com.

3 See Ancestry.com, 1900 United States Federal Census, record for Ernest Benson.

4 See Ancestry.com, 1910 United States Federal Census, record for Ernest H Benson.

5 See “Society” in The Telegram; “Benson Elected Captain of E.F.A. Football Team,” “Academy Show is Best Students Have Produced,” and “Academy Students Offer Fine Christmas Program.”

6 See “Dr. Leslie A. A. Benson, ’20.”

7 See “Elmira Boy an Aviator” and “Ground School Graduations [for September 1, 1917].”

8 Benson’s name—like that of Charles Edward Brown—does not appear on the rosters of men of the second Oxford detachment in the Penttinen Collection (see “Roster from Clayton Knight” and “Roster of Second Detachment”), and is not in the list of Oxford detachment men that Springs appended to the 1926 edition of War Birds. Sloan, Wings of Honor, does not include Benson’s name among the Oxford cadets, nor in the index, but does include it in Appendix V (“The Loners,” p. 410). I would have overlooked Benson entirely were it not for a list of men posted December 3, 1917, compiled by Foss, about which more below. Benson’s membership in the detachment is confirmed by the passenger lists for the Carmania’s September 18, 1917, voyage in the recently digitized War Department, Office of the Quartermaster General, Army Transport Service, Lists of Outgoing Passengers, 1917 – 1938.

9 Hooper, Somewhere in France, letter of [November] 4, 1917.

10 Grider, diary entry for November 14, 1917.

11 Grider, diary entry for November 14, 1917.

12 Foss, Papers, “Cadets of Italian Detachment Posted Dec 3rd.”

13 Hooper, Somewhere in France, letter of December 18, 1917.

14 Fleet’s photo of a February 18, 1918, crash at Stamford places him there during this period. For Maloney’s assignment to Stamford on January 26, 1918, see The National Archives (United Kingdom), Royal Air Force officers’ service records 1918–1919, record for C. B. Maloney. A remark by Clayton Knight puts Mooney at Stamford (see Kilduff, “Clayton Knight: Artist & Airman,” p. 206).

15 Hagan’s letter is among Benson’s miscellaneous papers and photos.

16 Benson, Pilot’s Flying Log Book. Unless otherwise noted, information about Benson’s flight training is based on his log book.

17 Benson gives the plane’s serial number as “9993.” Robertson, Military Aircraft Serials 1878–1987, indicates that both 9993 and B9993 were B.E.2c’s. Benson, like many pilots, was casual about providing letter prefixes, so he may have been flying either 9993 or B9993. Palmer’s logbook also records plane “9993″ as a B.E.2e rather than as a B.E.2c Possibly the plane they flew was built as a B.E2c but modified to be a B.E.2e.

18 O.C. is “officer commanding.” See “C.O. & O.C. – what is the difference?” for an explanation of this officer’s role.

19 See the graduation requirements given in, for example, Foss’s R.F.C. Training Transfer Cards.

20 Cablegram 874-S, dated April 8, 1918.

21 Cablegram 726-S.

22 Ibid.

23 Cablegram 955-R.

24 Benson gives the number 4009, which must be B4009—which, however, Robertson, Military Aircraft Serials 1878–1987, designates a B.E.2c.

25 See “Arrival Form” among the documents in Benson, Leslie A. A. Benson Collection, 1917-1919.

26 Cablegram 1303-R; Fleet’s comments are in a letter from him to Benson dated May 31 [1918] among the documents in the above-cited Benson Collection.

27 See Goettler’s diary entry for May 19, 1918.

28 The ration card (“Special Emergency Card), Fleet’s note, and the receipt are among Benson’s miscellaneous papers and photos.

29 On Gaines, see “Albert Belding Gaines, Jr., ’05.”

30 Dwyer, “Memorandum No. 8 for Flying Officer,” p. 4.

31 Bingham, An Explorer in the Air Service, p. 128.

31a See Schlotzhauer’s Pilot’s Flying Log Book.

32 There is an “Armée Américaine Permission” signed by Hiram Bingham to this effect among Benson’s miscellaneous papers and photos.

33 “History of Field 10 Third Aviation Instruction Center,” pp. 331–32.

34 See “Quota of Pilots Completing D. H.-4 Transformation Always Met at Field No. Ten.” (“Transformation” was the name given to the intermediate stage of observation pilot training; see History of Aerial Observation Training in the American E.F., p. 24.)

35 See Sloan, Wings of Honor, p. 410; among the photos Benson kept from this period is one labelled “Tours.”

36 The Officer’s record book is among the documents in Benson, Leslie A. A. Benson Collection, 1917-1919.

37 Moremen, “Air Service History, 258th Aero Squadron (Service).” Moremen, “Air Service History, 258th Aero Squadron (Service),” p. 46, implies a date closer to the Armistice. Sloan, Wings of Honor, p. 410, has Benson assigned to the 258th on November 20, 1918,

38 See Moremen, “Air Service History, 258th Aero Squadron (Service),” p. 46, for Holmes’s posting to the 258th. Benson kept a number of photos in which he identifies Holmes as his observer.

39 See account provided by James Albert Newman on p. 232 of Wycoff, Ripley County’s Part in the World War, 1917-1918. Wikipedia, “258th Aero Squadron” provides some information about the post-war activities of the 258th, giving Moreman (cited above) as the source. However, the information is not in Moreman, so the reliability of the Wikipedia article cannot be assessed.

40 Ancestry.com, U.S., Army Transport Service, Passenger Lists, 1910-1939, record for George R. Holmes.

41 There is a room ticket for the Hotel du Louvre in Paris dated June 14, 1919, among Benson’s miscellaneous papers and photos.

42 Ancestry.com, U.S., Army Transport Service, Passenger Lists, 1910-1939, record for Leslie A. Benson.

43 See “Dr. Benson’s Rites Set for Thursday.”