(Buffalo, New York, August 3, 1890 – September 2, 1918)1

Linn Humphrey Forster and his younger brother Frank Henri Forster were raised by their mother after the death of their father 1898.2 Linn studied mechanical engineering at Rensselaer Polytechnic, graduating in 1913, and then worked for Crosby Company, a metal stamping firm, in Buffalo.3 He was a member of the Second Aero Squadron, Signal Corps, New York National Guard, which was formed in Buffalo under the command of John M. Satterfield in the spring of 1916 in anticipation of possible use in the Mexican Punitive Expedition.4 Although not deployed, the 2nd Aero trained alongside the 1st at Mineola in 1916, and it is thus possible that Forster, like the men who attended ground school at Princeton, actually had some flying experience before going overseas.5 In any case, Forster went on to ground school at Cornell, graduating September 1, 1917.6

Forster was among the men from his class who chose or were chosen to train in Italy, and was thus one of the 150 men of the “Italian” or “second Oxford detachment” who sailed to England on the Carmania. They left New York for Halifax on September 18, 1917, and sailed from Halifax as part of a convoy for the Atlantic crossing on September 21, 1917. When they arrived at Liverpool on October 2, 1917, the men learned that they were to proceed not to Italy, but to Oxford, where they spent October repeating ground school at Oxford’s School of Military Aeronautics. In early November, twenty of the men, mainly ones who had flown at Princeton, were selected by the sergeant of the second Oxford detachment, Elliott White Springs, to go to Stamford for flight training, but most of the men, including Forster, travelled instead up to Harrowby Camp near Grantham in Lincolnshire to attend machine gun school, putting in time until there were openings at flying squadrons.

Fifty of the men left Grantham on November 19, 1917, for flying schools, but Forster was among those who continued at Grantham through Thanksgiving and the end of November.7

Finally, however, on December 3, 1917, the remaining men were posted to flying schools. According to a list drawn up by second Oxford detachment member Fremont Cutler Foss, Forster was one of the five men posted to No. 1 Training Depot Station at Stamford (the others were Edmond Thomas Keenan, Burr Watkins Leyson, Charles Francis Moore, and John Howard Raftery).8

Arrived at Stamford, Forster shared a room at “The Baths” with William Ludwig Deetjen, who was one of the second Oxford detachment members who had been at Stamford since early November. After the spartan accommodations at Oxford and Grantham, 16 Bath Row was luxurious: “We are by the bank of the little stream, and have a fine view from our front windows. . . . Now we have heat and hot water & free as well as frequent baths.”9 In mid-December Forster and Deetjen made an excursion to Nottingham where they met up with William Dolley Tipton of the first Oxford detachment; they went to the movies and tea with “the girls Linn knew,” then on to dinner, not arriving back at Stamford until nearly midnight, having “had the time of our lives.”10 The next day (December 13, 1917), Forster, who had been ailing for several days, went to hospital, where Deetjen visited him frequently; Forster returned to “The Baths” on about December 17, 1917. As Deetjen would be in Edinburgh over Christmas, he and Forster had a pre-Christmas celebration on December 23, 1917, lighting the tree Deetjen had been sent from home. They “shared a bottle of burgundy & drank to our mothers, our home, and the U.S.”11 On New Year’s Eve, the two of them “gave a little party to Mason & Eddy Foy. . . . We again lit our little tree, and later sallied forth to the Territorial Armory for Stamford’s great ball. . . . ’Twas some dance and I never hit home till 2 A.M. Linn never got home at all.”12 Days were taken up with classes and machine gun practice and, when weather and availability of planes permitted, practice flying on Curtiss JN-4s and DH.6s.

Deetjen and Forster evidently went separate ways once the former left for Waddington in mid-January 1918. His only further mention of Forster comes from a diary entry for February 19, 1918: “Got a letter from Linn who is at St. Albans that De Gamo [sic; sc. Degarmo] was killed in a Spad”; Forster was probably at one of the training squadrons at London Colney, near St. Albans.

Forster is one of many men whose appointments as first lieutenants Pershing recommended in a cable dated April 8, 1918; for some reason it took Washington over a month to send the confirming cable, which is dated May 13, 1918.13 Around this time, Forster apparently went up to the School of Aerial Fighting and Gunnery at Marske-by-the-Sea in North Yorkshire to train on S.E.5s, joining Marvin Kent Curtis, Glenn Dickenson Wicks, and Jesse Frank Campbell; on June 19, 1918, the latter, who had arrived at Marske on about May 18, 1918, wrote in his diary that “Wicks, Forester [sic], and myself started for Dover to fly Camels.” Campbell, and presumably Wicks and Forster as well, was stationed at No. 65 Training Squadron in Dover.13a

Two weeks later, on July 4, 1918, Forster was assigned to the American 148th Aero Squadron (a Camel squadron), joining Springs, Field Eugene Kindley, William Thomas Clements, and others from the Second Oxford detachment.14 Springs, in a letter to his stepmother dated July 18, 1918, indicates that Forster was in B flight, which he (Springs) commanded.15 148 was stationed at Cappelle Airdrome near Dunkirk, not far from the 17th Aero Squadron at Petite Synthe. Both squadrons, although American in personnel, were stationed on the British Front and remained under the tactical command of the R.A.F. until late in the war when they were moved south to the American Front. William P. Taylor, the squadron historian, describes the 148th’s activities at Cappelle:

. . . line patrols were soon started and after careful study of the map showing this sector, from the coast at Nieuport down to Ypres, most of it flat, marshy country where the line had been permanent for four years, the patrol leaders took their charges up to the edge of that awesome place, “Hunland,” and let them look it over. As aerial activity was comparatively quiet on this front, few Huns were sighted and day after day the line patrols were practiced without an attempt yet at offensive work. . . . After a week or more of line patrols the first offensive patrol over lines was made on July 20th, that of escorting the British “De Haviland-9″ bombing planes far over the lines to bomb the Belgian coast cities of Zerbrugge, and Ostend and also Bruges, inland some distance and over twenty-five miles into “Hunland.” The first escorting trip across the lines was made to Bruges and to many of the pilots it was the baptism of fire as the “Archie” bursts were continuous during the entire trip.16

Clements, who was in B flight with Forster, notes in his diary the many uneventful patrols and dud days in July, punctuated at the end by a “very, very warm day over Hunland.” B flight departed at 6:30 in the morning of July 31, 1918, led by deputy commander Harry Jenkinson, Jr. About ten miles into the patrol, they sighted a German balloon which they tried to go after, but they were discouraged by fierce anti-aircraft fire. “As we were getting back, four Huns came down on our rear man but did not get him. I thought once that poor Forster was gone. It was a pretty hot time.”17 Francis L. Irvin, one of the enlisted men in the 148th, recorded in his war diary for this day: “Lt. Forster’s plane shot up by Fokker.”18

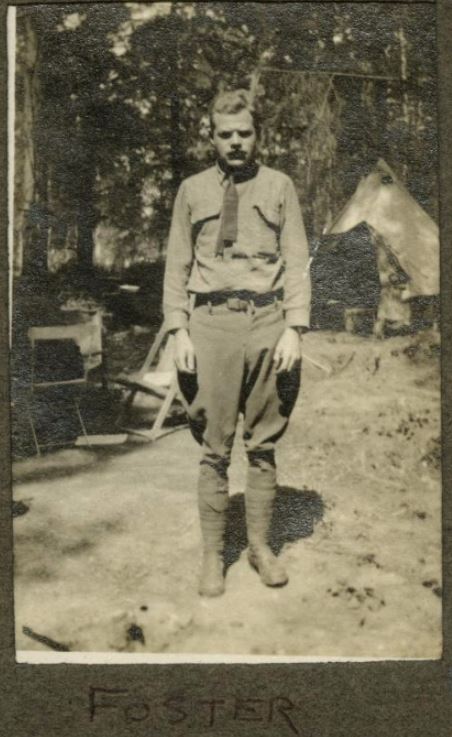

One of only two photos of Forster I have been able to find was perhaps taken the next day. Henry Robinson Clay, Jr., of the first Oxford detachment, who had been with the 148th since the beginning of July, created a photo album of the “148th American Squadron” that has the date “8.1.1918″ on the cover. On page 10 there is a photo labelled “Foster” that, given the context, is almost certainly of Linn Forster.19

Ready for work on a more active front, the 148th moved to Allonville, near Amiens, on August 11, 1918, three days after the British began their drive “to wipe out the Amiens salient which had been driven into their lines by the German spring offensive.”20 The 148th was “now attached to the Fourth British Army who were operating on the front from Albert to Roye and who were pounding away at the Hun and starting him back on that long and disastrous retreat which ended in capitulation.” The squadron’s work “was at once an entirely different and more serious proposition than that which they had just left.”21

Combat and enemy ground target attack reports are available for the 148th as part of Taylor and Irvin’s compilation, but not records of all missions flown. However, Springs’s flight log has been partially transcribed, and it indicates that Forster’s flight leader, once returned from sick leave at the end of July, flew nearly daily missions, sometimes twice daily, and Forster presumably did the same. Starting on August 13, 1918, Springs’s log shows numerous encounters with enemy aircraft.22

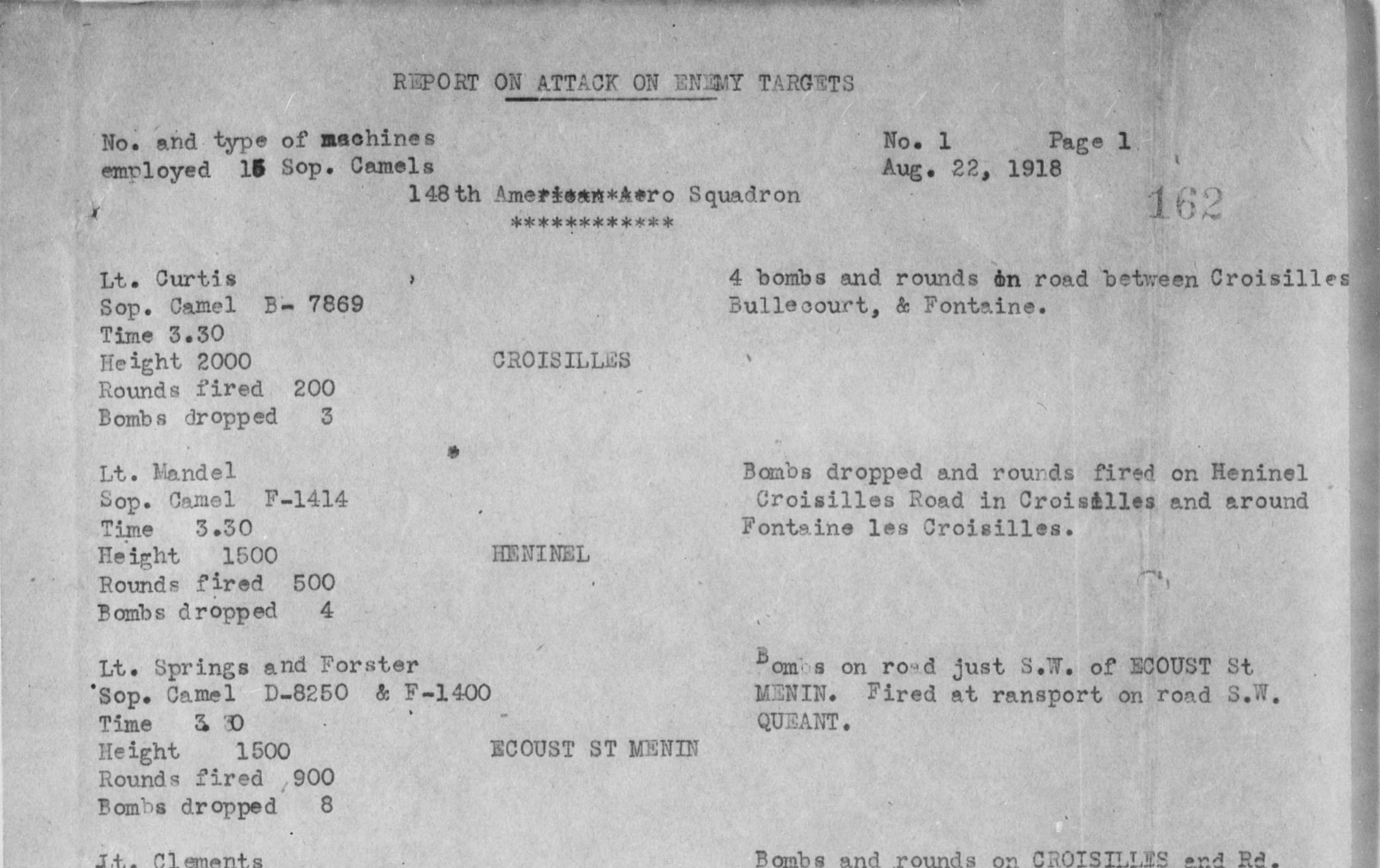

On August 18, 1918, the 148th was ordered to Remaisnil, about seventeen miles to the north, where they were attached to the Third British Army, commanded by General Sir Julian Byng.23 As the Third Army made its push towards Cambrai, the 148th, starting on August 22, 1918, undertook, in addition to their escort duties and offensive patrols, the particularly dangerous work of low bombing and ground strafing. The squadron’s “Report on Attack on Enemy Targets” for that day records that Springs and Forster, flying Camels D-8250 and F-1400 respectively, dropped, from a height of 1500 feet, “bombs on road just S.W. of Ecoust St Menin. Fired at transport on road S.W. Queant.”24  Similar reports appear for subsequent days. Forster took part in bombing and ground strafing on August 23, 24, and 26, while also taking part in offensive patrols. On August 27, 1918, he witnessed and attested to Springs’s downing of a Fokker biplane near Pronville during an “O.P.”25 Bad weather gave the pilots a respite until August 31, 1918, when once again “low strafeing [sic] [was] the order of things today.”26 Forster took part in bombing raids that day and the next.

Similar reports appear for subsequent days. Forster took part in bombing and ground strafing on August 23, 24, and 26, while also taking part in offensive patrols. On August 27, 1918, he witnessed and attested to Springs’s downing of a Fokker biplane near Pronville during an “O.P.”25 Bad weather gave the pilots a respite until August 31, 1918, when once again “low strafeing [sic] [was] the order of things today.”26 Forster took part in bombing raids that day and the next.

The next day, September 2, 1918, Springs’s flight log reads in part “1 hour 35 minutes. Canal du Nord. Disaster itself.”27 He wrote his father the next day: “Yesterday I got mixed up in the hottest battle of my experience.”28 His B flight was protecting observation and contact patrol planes when a number of Fokkers approached. Springs’s flight engaged them and shortly thereafter Kindley’s A flight came to their assistance.

Plainly the Huns meant business and so did we, so there you are. As soon as I would get on the tail of one Hun, another would get me and as soon as I would shake him off there would be another. Forster shot down one off my tail and got in a bad position himself. Two got him with one above waiting for me. He dove under me and I took the one on his tail. . . . I don’t know how many Huns we got out of it. I’m the only one of my flight who returned. . . .29

Kindley reports similarly: “I noticed one of our machines which I believe to be Lieut. Forster’s with three enemy machines attacking him so I went to his assistance and luckily shot down one of the enemy. By this time I was attacked by three of the enemy and of course had my hands full trying to defend myself.”30 Kindley gave the time of the fight as 11:50 a.m. Taylor’s squadron history reports of Forster: “Missing in action Sept. 2, 1918. Last seen fighting enemy aircraft between Rumaucourt and Arras-Cambrai Road.”31

![A newspaper clipping titled "Lieut. Linn A. [sic] Forster Reported Missing."](https://parr-hooper.cmsmcq.com/2OD/wp-content/uploads/Forster-MIA-Attica-News-article.jpg)

mrsmcq July 7, 2017

Notes

(For complete bibliographic entries, please consult the list of works and web pages cited.)

1 For Forster’s place and date of birth, see Ancestry.com, U.S., World War I Draft Registration Cards, 1917-1918, record for Linn Humphrey Forster. The photo is from p. 84 of the 1913 Transit, the Rensselaer yearbook.

2 For his father’s death, see Ancestry.com, New York, Wills and Probate Records, 1659-1999, record for Frank H Forster. See also Ancestry.com, 1900 United States Federal Census, record for Linn Forester [sic].

3 See Rensselaer Polytechnic Institute, Catalogue March 1918, p. 254, as well as Forster’s draft card, cited above.

4 See Ancestry.com, New York, New York Guard Service Cards, 1906–1918, 1940–1948, record for Louis [sic] Humphrey Forster, and “Lieut. Linn A. [sic] Forster Reported Missing.” On Satterfield and the Second Aero see Sweeney, History of Buffalo and Erie County 1914-1919, p. 309.

5 On the Second Aero and flight training, see Hennessy, The United States Army Air Arm, April 1861 to April 1917, pp. 177 and 180.

6 “Ground School Graduations [for September 1, 1917].”

7 Foss, Diary, entry for November 15, 1917.

8 Foss, “Cadets of Italian Detachment Posted Dec 3rd” (in Foss, Papers).

9 Deetjen, Diary, entry for December 5, 1917.

10 Deetjen, Diary, entry for December 13, 1917.

11 Deetjen, Diary, entry for December 27, 1917,

12 Deetjen, Diary, entry for January 2, 1918. Their guests were probably William J. Foy and Herbert Molloy Mason (sometimes apparently misidentified as Thomas Mason) of the first Oxford detachment.

13 Cablegrams 874-S and 1303-R; see here regarding the recommendation for “non flying” status mentioned in the latter cablegram.

13a See The National Archives (United Kingdom), Royal Air Force officers’ service records 1918–1919, record for Jesse F. Campbell.

14 See the roster of officers on pp. 61-63 of Taylor, A History of the 148th Aero Squadron.

15 Springs, Letters from a War Bird, p. 181.

16 Taylor, A History of the 148th Aero Squadron, pp. 26 & 27.

17 Clements, “World War Diary of W. T. Clements 1917-1918,” entry for July 31, 1918. Note: Forster’s name is spelled “Foster” by Clements or his typist.

18 Taylor and Irvin, Francis L. “Spike” Irvin’s War Diary and The History of the 148th Aero Squadron Aviation Section, p. 13.

19 Clay, “148th American Squadron Album.” Skelton and Williams, Lt. Henry R. Clay, reproduce the picture as no. 48 with the same identification.

20 Hudson, Hostile Skies, p. 210.

21 Taylor, A History of the 148th Aero Squadron, p. 29.

22 See Springs, Letters from a War Bird, Chapters 6 and 7, passim; the entry for August 13, 1918, is on p. 198.

23 Taylor, A History of the 148th Aero Squadron, p. 31.

24 For Forster’s participation in this and subsequent attacks see the bombing reports on pp. 162–89 of Taylor, A History of the 148th Aero Squadron.

25 See combat report on p. 115 of Taylor, A History of the 148th Aero Squadron.

26 See Irvin’s diary entries for August 28-31, 1918, on p. 15 of Taylor and Irvin’s Francis L. “Spike” Irvin’s War Diary and The History of the 148th Aero Squadron Aviation Section.

27 Springs, Letters from a War Bird, p. 221.

28 Ibid.

29 Ibid., p. 222.

30 Quoted on pp. 121-22 of Ballard, War Bird Ace. Forster is spelled “Foster” in the quoted passage.

31 Taylor, A History of the 148th Aero Squadron, p. 56. Skelton, in Callahan, the Last War Bird, states that “Forster, Kenyon and Mandel were shot down by Leutnant Ernst Bormann” (p. 43). Henshaw, The Sky Their Battlefield II, more cautiously notes a Camel claim by Dahlmann and three by Bormann in the general area.

32 “Lieut. Linn A. [sic] Forster Reported Missing.”

33 See “Linn H. Forster,” CWGC/ABMC [pseud.], “1LT Linn H. Forster,” and Boone, “Lieut Linn Humphrey Forster.”

34 See Ancestry.com, New York, Abstracts of World War I Military Service, 1917-1919, record for Frank H Forster, as well as “Lieut. Linn A. [sic] Forster Reported Missing.” The nephew’s name and date of birth are taken from hollyforster, “Forster Thomas Family,” page for Linn Humphrey Forster M.D.

35 See Ancestry.com, New York, Passenger Lists, 1820-1957, record for Jessie Forster; Wikipedia, “Gold Star Mothers Club.” (Note: according to census documents, Jessie’s father’s name was Humphrey Humphreys.)