(Wichita, Kansas, October 10, 1890 – Fort Myers, Florida, December 24, 1957).1

Thetford & London Colney ✯ Marske & Joyce Green ✯ France & the 148th Aero ✯ August 24, 1918 ✯ P.O.W. ✯ After the armistice

Curtis was the great-grandson and namesake of Marvin Kent, for whom Kent, Ohio, was named, and great-nephew of William Stewart Kent, who was involved in the establishment of Kent State University.2

After high school in Chicago, where his father was in the fire insurance business, Curtis attended Amherst College (class of 1914).3 He then began teaching at Wentworth Military Academy in Lexington, Missouri.4 During the summer of 1917 he was slated to act as the director of Wentworth’s Boundary Canoe Trips program for teenage boys in northern Minnesota, but his application to the Signal Corps supervened.5

Curtis entered ground school at the University of Illinois in early July 1917, graduating on August 25, 1917.6 About one third of the men in this class, including Curtis, chose or were chosen to go to Italy for flight training and were thus among the 150 men of the “Italian” or “second Oxford detachment” who sailed to to England on the Carmania. They departed New York on September 18, 1917, and, after a stopover at Halifax to meet up with a convoy for the Atlantic crossing, docked at Liverpool on October 2, 1917. “We were somewhat disappointed on landing to learn that our plans had been entirely changed, but we are delightfully situated, and the prospect of a winter in England is not bad.”7 They were to attend ground school, again, this time at the Royal Flying Corps’s No. 2 School of Military Aeronautics at Oxford University. About sixty of the men were housed at Queen’s College, with William Ludwig Deetjen in charge, but Curtis was with the larger group under Elliott White Springs at Christ Church College; there is a photo of him and three fellow cadets (as they were now called) standing in Christ Church’s Peckwater Quadrangle. Curtis took tea with Sir William and Lady Osler the Sunday after he arrived at Oxford, and sometime early in his stay bicycled to Blenheim Palace with Charles Edward Brown, his roommate, and John McGavock Grider, Clarence Horne Fry, and Laurence Kingsley Callahan.8

On October 14, 1917, the men of both the first and second Oxford detachments were inspected by a West Point major, Gordon Robinson, recently arrived in Europe. The upshot was that they all had to purchase, at their own expense, complete new uniforms.9 This was the start of money problems that would dog some of the men, including Curtis, and that were exacerbated as time went on by delayed and curtailed pay. As Curtis’s fellow detachment member Parr Hooper wrote: “I am about dead broke, but that is all. Uniform, quilt, $3 for seat in a theatre, 1st class railroad fare and all take the cash. Officers here are not permitted to go to any but the best hotels, best seats in the theatres, lst class railroad coaches. We are not officers, do not get officers’ pay but are supposed to conduct ourselves as officers.”10

On November 3, 1917, Curtis was among the approximately 130 men who left Oxford and set off for Harrowby Camp, a machine gun school at Grantham in Lincolnshire. During his brief time there he enjoyed a dinner at Stoke Rochford Hall, home of Christopher Hatton Turnor, about four miles south of Grantham: “The place is one of the show places of Lincolnshire—a marvellous country house with 45,000 acres of land around it.”11

In mid-November, fifty of the Grantham men, including Curtis, were selected to go on to flying schools.12 Curtis was assigned to No. 12 Training Squadron at Thetford in Norfolk. He wrote his father on November 21, 1917, on R.F.C. Thetford letterhead: “The boys here with me are Grider, the Arkansas boy you met in N.Y., Callahan of Chicago, Brown of Lake Forest, and Fry of Columbia Tenn.” “We are training on Maurice Farman machines, pushers,” i.e., with the propeller behind the cockpit. In a letter to a friend back at Wentworth, he described the Maurice Farman as looking like “a cross between a box-kite and a bird cage.”13 On December 18, 1917, he wrote his sister Josephine: “Today has been an important one, for I started on my first solo flying, and got in two hours and forty minutes without mishap, except for breaking one landing skid.” Two days later: “On these clear cold days it is a wonderfully exhilarating sensation to see the sun rise when you are alone in a machine about 2000 feet.” He “graduated with honor and a whole skin from an elementary squadron and [was] recommended for scout machines.”14

On December 21, 1917, Curtis was assigned to No. 74 (training) Squadron at London Colney; he arrived there Christmas Eve.15 He was billeted at the Red Lion in Radlett, along with Fry, Joseph Frederick Stillman, Conrad Henry Matthiessen, Glenn Dickenson Wicks, and Austin Finley Morrison.16 James Ira Thomas Jones (“Taffy” Jones) was also training at No. 74 and later recalled the influx of Americans: “Our school was lucky enough to get such grand types as Ken [sic] Curtis (a wizard at the piano, and no mean caricaturist). . . .” 16a Curtis described the aerodrome itself as “rotten,” but “Our mess is very congenial.”16b He evidently contributed to the congeniality. Another 74 Squadron pilot, Harris George Clements, recalled how “[Edward Corringham ‘Mick’] Mannock was once in our Mess while Curtis was playing the piano and before long Mannock was playing on a tankard with his kettle drum sticks. We all joined in and soon had a jazz session going.”16c

Other members of the second Oxford detachment were just across the field at No. 56 T.S. at London Colney, and they socialized together and shared training planes. Hooper, at No. 56, took a photo in early January of Curtis together with Fry, also at No. 74, and Brown and Robert Alexander Anderson from No. 56, all warmly bundled up in front of an Avro at London Colney.

After Grantham the proximity to London proper was welcome, and Curtis was able, among other things, to socialize with the family of John Tweed (“the Empire sculptor”). Mr. Tweed was in France with General Smuts, but Curtis took Ailsa Tweed, who was apparently a friend of Josephine, to tea at the Savoy and to the theater, and dined at her home.17

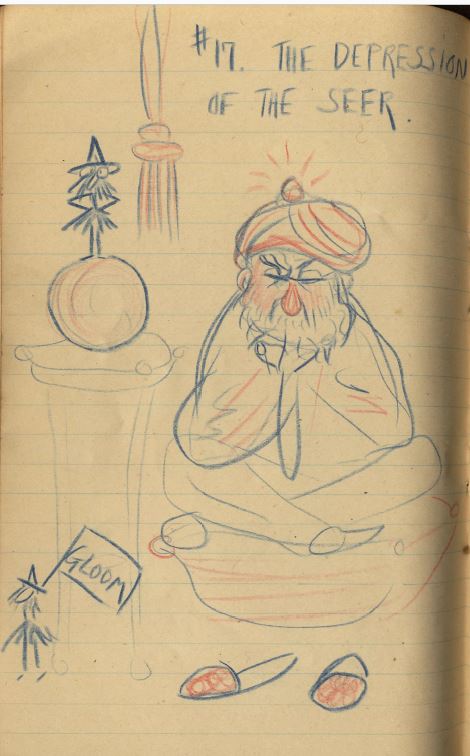

The excitement of flying at London Colney was offset by the boredom of classroom instruction. The War Birds entry for January 3, 1918, recounts how Curtis drew pictures in his notebook when he was supposed to be paying attention in machine gun class. The sketches were amusing enough that, when caught out, he was not reprimanded, but asked to reproduce them on the walls of the C.O.’s office.18

On February 27, 1918, Curtis wrote his sister: “Another graduation event is nearly upon me. Today I made a cross country flight alone, and landed at two strange aerodromes, thus completing all tests for graduation to the one seater scouts.” He also reported having been a pall bearer at the funeral of his roommate Stillman the preceding day.

On March 5, 1918, Curtis went across the field at London Colney to No. 56 Training Squadron. Finances were beginning to look up, and this “enabled me to do something I should have hated to miss, i.e., the farewell dinner of the –th Squadron R.F.C. in a big London restaurant before flying overseas. I was the only American present, in fact the only guest outside of the officers going over. The Major presided and I had to make a speech. . . .”19 Censorship concerns prompted Curtis here and elsewhere to err on the side of caution and not name the squadron. He probably attended the farewell dinner, on about March 23, 1918, for No. 74 Squadron, formerly his training squadron, now operational. The above-mentioned Clements recalled that the restaurant was the Criterion; the major would have been Keith Caldwell.20

In a letter from April 9, 1918, he wrote his father: “Yesterday was a rather eventful day in my training. I made my first flight in a single-seater scout machine.” Here, as later when mentioning flying milestones in his letters home, Curtis does not give the name of the machine, which his log book records as Sopwith Pup [C]270.21 In the same letter of April 9, 1918, Curtis noted that he had the preceding day “graduated as a service pilot (of course there are several weeks more training before I qualify for overseas)” and that he had been recommended for a commission as a first lieutenant on March 27, 1918. His next letter, to Josephine, from April 13, 1918, was written on the letterhead of the Victoria and Albert Hotel at Torquay in Devon where he and Fry were reveling in four days graduation leave.

Back at No. 56 T.S. at London Colney Curtis endured a period of no flying due to bad weather and worried about the delay in getting his commission. But towards the end of April he felt he was “getting more like an aviator everyday—yesterday I flew the last word in aeroplanes—a stationary scout. By stationary it is meant that they have not a rotary engine. They are small and heavy and fast. I was going 130 miles an hour most of the time.”22 His pilot’s log book for April 27, 1918, records his flight on Spad [A]9135. He goes on to remark that “Fry is still with me. We’ll probably finish with this squadron at the same time.” Both of them were anticipating being sent to Scotland for aerial fighting training.23 But Fry was killed when the Spad he was flying crashed on May 4, 1918. Curtis wrote his sister on May 8, 1918, from Lynton in North Devon: “I was feeling pretty rotten after poor old Fry’s funeral yesterday, so they gave me two days leave and I came down here to rest up. . . . Fry was killed last Saturday. It was a great blow to all of us—but to me especially I think, because we had been pretty close friends since November first, when we went to our first aerodrome together.”

Later in the month Curtis was posted not to Ayr in Scotland, as he had expected, but to the School of Aerial Fighting and Gunnery at Marske-by-the-Sea in North Yorkshire; he, along with Jesse Frank Campbell and Wicks, left to go north with on May 18, 1918.23a It was a “bit of a come down,” he wrote his father on May 19, 1918, “to live in huts, after being billetted in a hotel for so long.” His hut mates were Brown (with whom he had roomed at Oxford and Thetford) and John Hurtman Fulford, “both Cadets, as I still am”—word of the cables confirming their commissions had evidently not yet trickled down to any of them. His next letter, to his sister on May 25, 1918, was more cheerful: “I am now a real first lieutenant. . . . This is a rather nice place . . . we live in comfortable huts by the sea, and the aerodrome itself runs right down to the beach. I took a plunge in the surf the other afternoon. . . .”

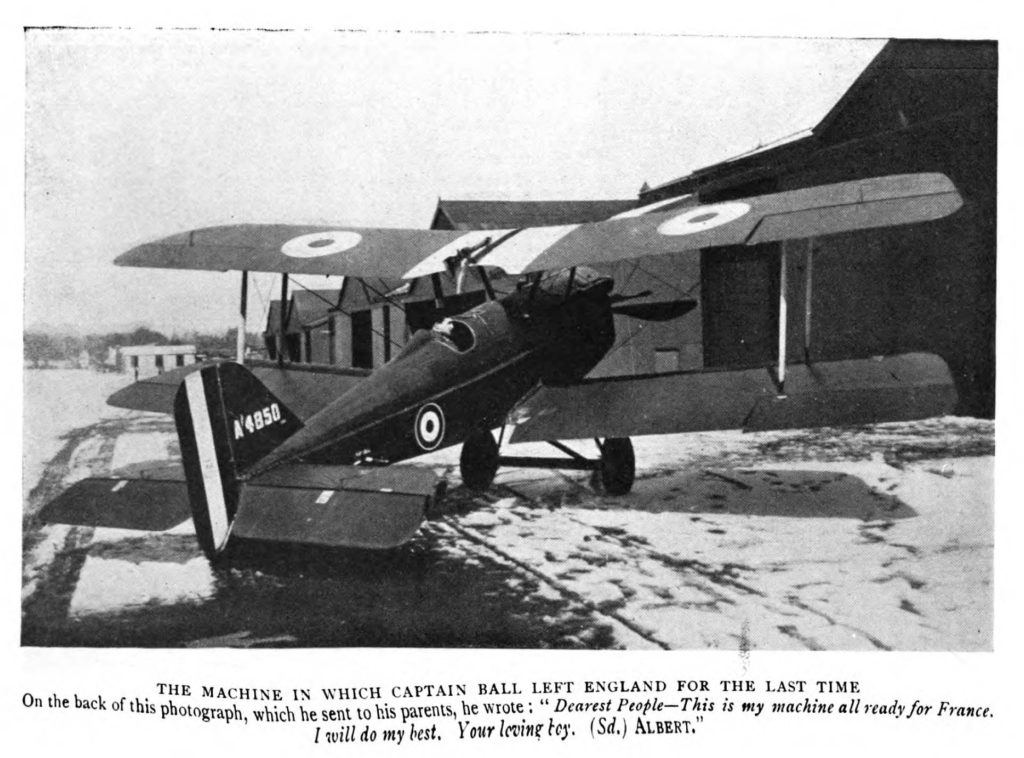

He goes on to remark: “The more I see of it, the more I like the scout machines, the one-seaters.” He still avoids giving the name of the airplane, but urges Josephine to read Captain Ball, V.C.: “two of the photographs in the book were taken of him at our old aerodrome, about a year ago, and show the service machine that I am flying.” Curtis was almost certainly referring to an S.E.5, although, according to his log book, he did not actually fly this type until June 7, 1918, when in his “1st solo on S.E” he was “fighting a Bristol.” His remaining training at Marske focussed on aerial combat, and he twice fought “Brownie,” (Brown), once from an Avro with Brown in an S.E.5, once from an S.E.5 against Brown and Capt. Fielding-Johnson in the Avro.24

Curtis’s commission, recommended by Pershing in a cable dated April 2, 1918, was among the many recommended in ten cables from Pershing between March 30 and May 4, 1918, that were finally confirmed en masse on May 13, 1918.25 In a memo dated May 29, 1918, Geoffrey J. Dwyer, who had charge of the American R.A.F. trainees in England, acknowledged that the men had been poorly treated: “Owing to the injustice done cadets in England, . . .”26 Curtis quotes this phrase in a letter to his father on June 5, 1918, in the context of his ongoing financial concerns. “However, the weather is fine, and I am with a good bunch of chaps, and stand a good show of getting with a squadron that I know in France. They have brought down about 40 Huns since they went out six weeks ago.” He was presumably hoping to be assigned to No. 74. He was gaining confidence and ten days later remarked that “I think I am a fairly good fighting pilot now—my eyes are good, and they tell me that and formation flying are the two prime necessities to a long life over the lines. I am going out on the best machine that flies, and with an English squadron (as far as I know.)”27

However, the higher ups were making different plans. Curtis, having graduated at Marske on June 18, 1918, “travelled over a good bit of England and finally am settled at an aerodrome near here [London] to learn on a new type of machine before going overseas. None of us are pleased at the change, but we are told that the new American squadron must fly them until aeroplane production at home speeds up enough to give us the more advanced type. . . . My present aerodrome is on the Thames estuary, the path of the German raiders. They haven’t come over much recently, but if they do I may see my first service as a home defense pilot flying at night.”28 He was now assigned to No. 63 Training Squadron at Joyce Green and learning to fly Camels.29 (The same switch had been pulled on an indignant Eugene Hoy Barksdale, who protested, successfully, and went back to S.E.5s.)

When he finished at Joyce Green at the end of June 1918, Curtis had flown a total of fifty-eight hours, just over forty-one of them solo. He had had forty-five minutes on S.E.5s (two flights at Marske) and nearly nine hours on Camels (fifteen flights at Joyce Green—including twenty minutes on a “dual type” Camel, [B]7445).

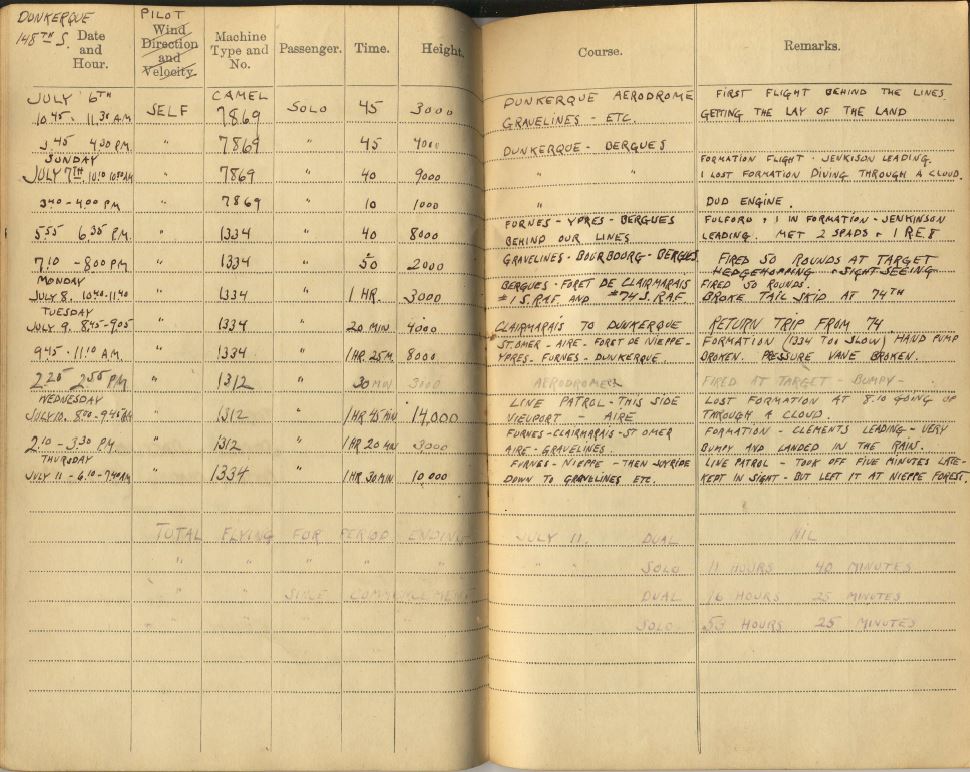

On July 3, 1918, Curtis wrote his father “tomorrow morning I leave for France with three other Americans. . . . I’m going over by boat, not by air.” The three other Americans were probably Forster, Fulford, and Walter Burnside Knox; they and Curtis joined the British Expeditionary Force as Camel pilots assigned to the U.S. 148th Aero Squadron on July 4, 1918. Once arrived at the squadron, all but Knox were assigned to B flight, led by Springs.30 148 had arrived at the Capelle airdrome near Dunkirk, not far from the 17th Aero Squadron at Petite Synthe, on July 1, 1918. Both 17 and 148, although American in personnel, were stationed on the British Front and under the tactical command of the R.A.F. until late in the war when they were moved south to the American Front.

Springs had health and vision problems and apparently did not fly between July 6 and July 29, 1918; he was running “my flight from my sidecar and my deputy leader leads the flight.”31 But he was hardly bedridden. Curtis recounts in a July 14, 1918, letter to his father how “yesterday . . . Elliot Springs, Jack Fulford and I got the C.O.’s touring car and a driver and were driven about thirty miles cross country to the –th Squadron R.A.F. . . and we had dinner with them. The ride was lovely—it was just before sunset. . . . A Hun raid was in progress just as we started back.” Driving without lights, they finally arrived back at the aerodrome, “and I tumbled into my cot-bed at 2:30 A.M. At 3:15 A.M. my batman shook me awake and said, ‘Your tea’s ready in the mess, sir, and the patrol leaves the ground at 4.’ I . . . watched the sunrise from 14,000 feet.” They had probably dined at Springs’s former squadron, No. 85. R.A.F., at St. Omer.

This early morning patrol was already Curtis’s fifteenth; he had made his “first flight behind the lines getting the lay of the land” on July 6, 1918. This was followed by formation flying with sometimes Harry Jenkinson, sometimes William Thomas Clements leading; Jenkinson—who had trained with the R.F.C. in Toronto and flown for a time with No. 73 R.A.F.—was filling in for Springs, and Clements was serving as his deputy.32 On Monday, July 8, 1918, Curtis had the opportunity to fly down to Clairmarais where the R.A.F. squadron he had hoped to serve with, No. 74, was stationed, coming back the next morning; Leonard Atwood Richardson of 74 noted this visit in his diary on July 8, 1918.32a The first line patrol Curtis records flying took place on July 10, 1918: “line patrol, this side Nieuport–Aire.”33

On July 19, 1918, Curtis wrote his sister: “Yesterday morning on a patrol, we worked at 14,000 feet and we could look into four countries at once” (“Belgium, Holland, France, and a fringe of England,” as he later described it.34) He helped ensure that the 148th was properly equipped: “I am going into town by motor this afternoon to see about a piano for the mess.” He went on in the letter of July 19 to remark: “We are fairly busy but not really offensive yet—just getting acquainted with the work.” The next day the squadron flew its first offensive patrol.35

Curtis participated in his first offensive patrols two days later, and his first log book entry for July 22, 1918, notes “got archied uncomfortably close over Ostend”; he flew another patrol in the afternoon. On his fourth O.P., on July 25, 1918, he noted: “dived on by five Fokker biplanes over Nieuport.” His next flight was an “escort to 211 Squadron of D.H.9s bombing Bruges.” Clements describes this work in his diary on July 20, 1918: “This is rather bad business, escorting D.H.9’s over, as they can go higher than we can and are faster at a height. [Camel] 140 Clerget engines are no good above 15,000 ft. at all and bombing machines seldom travel at anything else.”

A few days later, on July 31, 1918, Curtis flew a “line patrol with Springs,” who was once again able to lead B flight. Like Clements, Curtis was aware of the limitations of their increasingly obsolescent Camels as they began encountering the new German Fokker DVII. “We are carrying on as usual at the squadron. We have been in some more scraps, but owing to the limitations of the machines we are flying we have brought down no Huns yet. The Hun scouts are always miles above us, and usually just sit there, and we can’t get that high.”36

On August 11, 1918, the 148th moved about seventy-five miles south, from the relatively quiet northern front to Allonville near Amiens: “We moved Sunday—and flew to a new aerodrome—in a sector that you are reading about more in the papers than that we left. . . . From all we can learn, the Hun must be on the run—we do know this; our aerodrome was within four miles of the line a month ago, and now we have to fly about twenty minutes before we get over Hun territory. . . . We had to leave our piano at the old place because we are too mobile here.”37 On August 12, 1918, “on my first patrol in our new sector I lost my formation on the way home. I flew around for half an hour above the clouds, diving down occasionally to get my bearings—finally I saw a French aerodrome and I landed. The pilots were most cordial and insisted that I stay for lunch. . . .” His log book records his landing at Esquennoy, about twenty miles south of Allonville. Curtis spoke French and enjoyed the chance to socialize with the French aviators. “I got back to my own aerodrome in twenty minutes. They had not yet reported me missing because I had last been seen on our side of the lines.”38

A few days later, on August 18, 1918, the 148th was ordered to Remaisnil, about seventeen miles to the north, where they were “attached to the 13th Wing of the Royal Air Force and the Third British Army.”39 The nature of the squadron’s activity changed soon after this move. From Remaisnil they were to support the British Third Army with bombing and low altitude strafing. On August 21, 1918, Curtis was part of a flight escorting R.E.8s, but on August 23, 1918, his two missions were bombing and ground strafing raids. On the first, which started mid-afternoon, “[Oscar] Mandel and I on Heninel & Fontaines. Shot 200 rounds at transport on Fontaine-Bullecourt Road.” In the evening, “Ground strafe, bomb raid on Ligny-Thilloy. Broken belt in left hand gun.”40

The next evening, August 24, 1918, Curtis took off in Camel B7869 at 5:50 p.m. on a raid over Beaumetz-lès-Cambrai on the road from Bapaume to Cambrai. Curtis was paired with fellow second Oxford detachment member Walter Burnside Knox, who reported dropping his bombs from an extremely vulnerable 700 feet. The entry for Curtis in the relevant bombing report states “Not returned at 8:20 PM.”40a

The following day Springs wrote to his stepmother: “I went out about five last night loaded with specially selected lead pellets and took Forster along with me. [Johnson] Kenyon went a half hour before and Curtis was to come a half hour later. . . . I got back. . . . Forster had already gotten back safely but Kent Curtis was shot down by one of the Huns. A fine fellow he was, possessed of an excellent sense of humor, once a teacher of French and German at a Missouri college, once a guide in the northern woods, and a gentleman above reproach. His witty remarks will long ring in my ears, and he was a musician with few equals.”40b

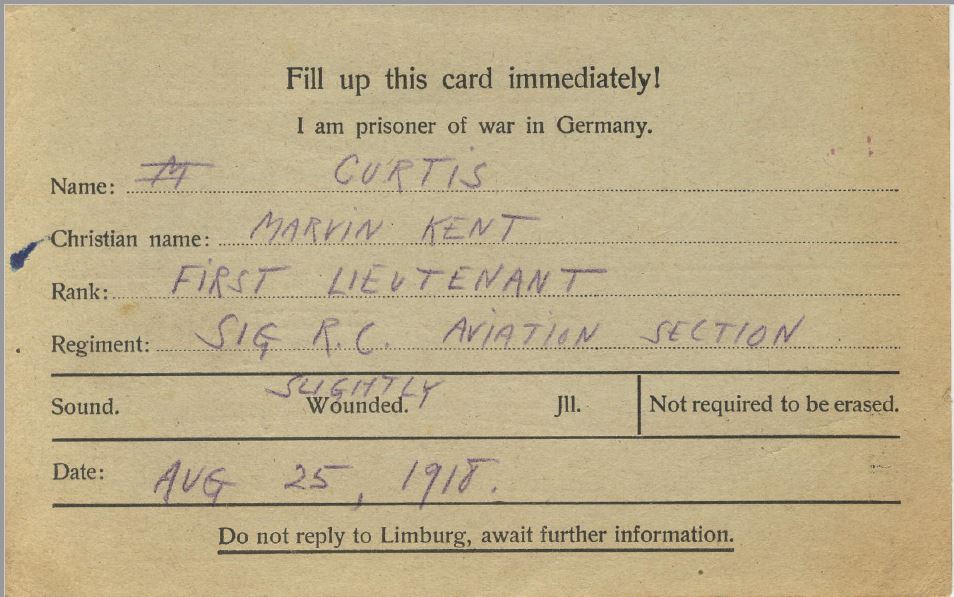

Despite having filled out a “Kriegsgefangenensendung” card addressed to his father stating that “I am a prisoner of war in Germany” the day after he was shot down, Curtis was for some time assumed to have perished, having apparently been reported to his squadron as “down in flames.”41 Towards the end of September “Marvin K. Curtis” appeared on the official casualty list, reported as having died from wounds.42

In early October, Curtis’s squadron received good news. Two days after Curtis was shot down, William Dolley Tipton of the 17th Aero Squadron (and the first Oxford detachment) was also shot down and, taken prisoner, encountered several American pilots, including Curtis, in similar circumstances. He sent a post card with news of himself and the others to the Aviation Office in London. The card was forwarded to the 17th, whence news of Curtis was apparently passed on to the 148th. The entry for October 4, 1918, in the diary of Francis L. “Spike” Irvin of the 148th reads in part: “Report received that Lt. Curtis is a prisoner,” and the roster of officers in Taylor’s history of the 148th notes in the remarks column for Curtis: “On Oct. 6th, reported a prisoner of war from an unofficial though reliable source.” In a letter to his father dated October 12, 1918, Springs reported: “Three of the men I lost have been reported as prisoners. Curtis, Mandel, and Kenyon.”42a And, at some point, in the midst of letters of condolence, Curtis’s mailings from various P.O.W. camps finally reached his family.

On December 3, 1918, in temporary quarantine at Base Hospital 26 at Allerey-Sur-Saône, France, Curtis wrote his father a long letter that, among other things, describes the circumstances surrounding his capture on August 24, 1918: “It was my third show at this [low bombing and strafing] that my machine was shot out of control from the ground and I crashed into a German trench and turned over. I was not hurt—just cut about the face—but I had quite a time getting out of the wreckage. I was taken prisoner immediately. . . .”

More detail is provided by an official account in Presenting the Experiences of Air Service Officers who were Prisoners of War in Germany.

On a very cloudy afternoon in August [Curtis] left the aerodrome at Remaisnil accompanied by one other pilot, an Englishman [sic]. Their mission was to bomb and machine gun traffic on the roads east of Beaupaume [sic], carrying the usual load of four twenty-five pound bombs for this work. They were not far from their objective when Lieut. Curtis, who was leading, dove under a cloud and, when he came out on the other side, found that he had lost his companion. He continued the journey alone and when he reached Baupaume [sic] shut off his motor and glided down to an altitude of 1000 feet. Seeing transport on the Baupaume-Fremincourt [sic] road he set out for it but just at this moment discovered five Fokkers above him. Hurriedly releasing his bombs he struck out for home and a healthier neighborhood. But the Fokkers did not dive on him. . . . This was encouraging but it was only a moment until a second Fokker formation appeared, flying between Curtis and the lines. He decided that the best chance of showing up at mess that night was to “hedge hop” home so descended to within twenty feet of the ground. The Fokkers did not bother him at this altitude but it gave the machine gunners on the ground a wonderful opportunity and they were quick to take advantage of it. Their aim was good and his right wing suddenly dropped and he crashed into a shell hole turning the machine over.43

Largely unscathed, Curtis was getting clear of his machine when he was surrounded by enemy soldiers and unable to burn his plane. His December 3, 1918, letter to his father continues the story: “I was taken prisoner immediately, and led to a dressing station in Bapaume—the town mostly in ruins, but there was a dressing station in the wreck of a sugar factory. I walked miles that evening and then rode horseback until 2 A.M. and slept on the floor of a stable”; the P.O.W. narrative in Gorrell indicates he walked to Morchies and rode to Baralle. From there he travelled on foot and by train via Ecourt-Saint-Quentin (whence he sent a first P.O.W. card to his father) and Arleux to Douai. At Douai he was quartered in a house with George Thomas Wise, of the 17th Aero Squadron, who had been brought down and captured the same day (August 24, 1918) as Curtis, also in the vicinity of Bapaume.

From Douai, Curtis was taken to Camp Friedrichsfeste at Rastatt in Baden; he sent a card dated September 6, 1918, to his father to let him know of the change of location. Apparently the next day he acquired the notebook in which he kept a sketchy diary and also recorded the names of the other P.O.W.’s he encountered; a number of them wrote their names and addresses in the book. The men who apparently did so at Rastatt were Franklin F. Jewett of Chevy Chase, Maryland; Vivian Harley from Pretoria, South Africa; Johnson D. Kenyon from Wauseon, Ohio, who had, while flying with the 148th, been shot down September 2, 1918; Roger F. Chapin from Boston; Edwin C. Klingman from North Carolina; and G. L. [Guy Lord] Carter from Carnarvon, Wales.

According to the diary, Curtis, along with Wise, Tipton, and Robert Haber Ellis, an American who had been in No. 56 Squadron R.A.F., was transferred on September 17, 1918, to the Europäischer-Hof Hotel in Karlsruhe, where they shared room 38. (This was the “listening hotel,” with hidden microphones and dictaphones that were intended to capture intelligence from the prisoners’ conversations with one another.44) “There I stayed eighteen days, rooming first with Wise, Tip, and Ellis, then with —gdale and Capt. [William George] Shedel, then in solitary.” Curtis’s narrative is discontinuous and not entirely comprehensible, but he apparently also roomed with “[Arthur Lincoln] Clark, [William Landon] Bradfield & Sgt. Hall, then with Kenyon, Jewett & Harley in a ground floor room with slightly more liberty.”

“Then on Oct 4 (happy day) we moved to the lager & installed ourselves with Polacek and some English [ta?]nk officers.” Evidently the P.O.W. camp at Karlsruhe was preferable to the hotel; Curtis goes on to remark that “life at Karlsruhe was pleasant. Lt. Shea of the Red Cross Committee gave us plenty of food. There was a good library, piano, and a concert on Saturday night.” On October 6, 1918, he wrote his father: “I am well, and with friends. I think I wrote that there was a chap from Wauseon in my squadron—he is now a prisoner and we are rooming together.”

Three days later, Curtis and Kenyon, along with Carter, Shedel, and Harley, left Karlsruhe and, travelling via Stuttgart and Munich, arrived the evening of October 10, 1918, at Landshut in Bavaria. There Curtis and Kenyon rejoined Wise, Ellis, Jewett, and Chapin; they were housed in Trausnitz Castle. They were welcomed by a self-appointed Red Cross committee of P.O.W.’s consisting of James Norman Hall, Robert George Browning, and Henry Carvill Lewis.

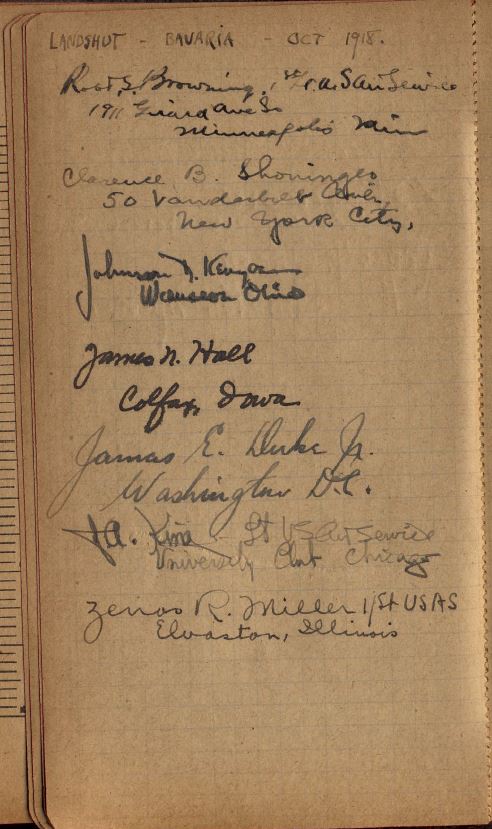

While at Landshut, several of the P.O.W.’s entered their names and addresses in Curtis’s book: Robt. G. Browning of Minneapolis; Clarence B. Shoninger of New York City; Johnson D. Kenyon of Wauseon, Ohio (for a second time); James N. Hall of Colfax, Iowa; James E. Duke of Washington, D.C.; J. A. [John Andrews] King of Chicago; and Zenos R. Miller, from Evanston. (And Curtis reciprocated; he wrote his name, rank, address, and date and place of capture in Miller’s diary.44a)

Two weeks later, on October 24, 1918, twenty prisoners, including Curtis and Kenyon, left Landshut to travel back west across southern Germany to a prison camp at Villingen in the Black Forest. Once arrived there, “Kenyon and I went into the mess with A. M. Roberts, Horace Wells, and [Harold A.] MacChesney.” On October 27, 1918, Curtis wrote his father that “I think I am settled in a permanent camp now.” Fortunately, the word “permanent” was soon rendered meaningless by the armistice.

Curtis remained at Villingen until November 26, 1918. Then “we left V. and were held in Constance on the Swiss border, until our people and the Swiss could make arrangement for transportation. . . . The morning of the 29th, we boarded the train . . . and in a few minutes were over the border. Swiss people were along the tracks waving French and American flags. At Zurich, Berne, Lausanne, and Geneva we were met by crowds and the Red Cross brought us hot coffee, food, chocolate, cigarettes and every conceivable kind of gift. At midnight we went through a great tunnel and emerged into France at Bellegarde. . . .” From there, Curtis was transported to the base hospital in Allerey-Sur-Saône. “Incidentally, I have crossed Caesar’s three great rivers, the Rhine, the Rhone and the Danube, the last at Ulm in Wurtemburg.”45

When Curtis was released from quarantine around December 12, 1918, he set out to “get on the trail of my kit, my mail and my squadron.”46 After seeing Fry’s brother William at Chaumont, he went to Paris, and thence to Toul, where he found his squadron, a cache of letters from home, and the news of his sister’s marriage (“you can imagine that it was like waking from the dead to find all the news that had accumulated during my stay in Germany”), but not his kit, which was apparently permanently lost.47 He was given some leave, during which he enjoyed exploring warmer parts of France, and then returned to England, and finally, in February 1919, home on the Canopic.48

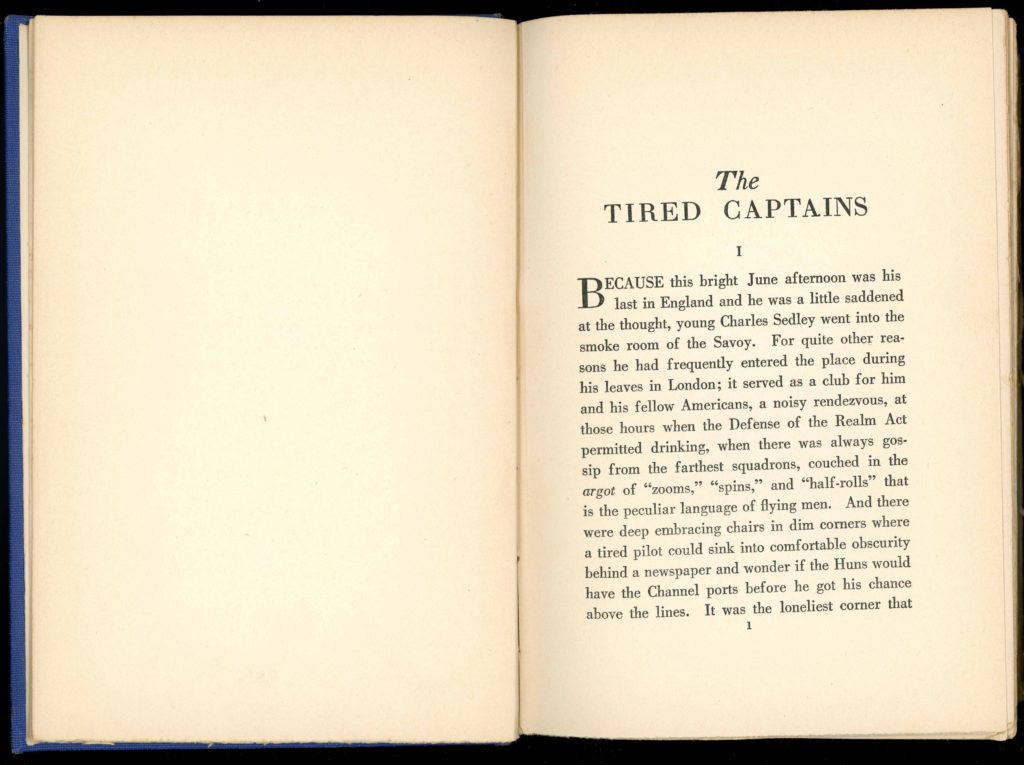

Curtis returned to teaching and a writing career; his The Tired Captains, published in 1928, draws on his experiences in the war and is well worth reading.

Curtis returned to teaching and a writing career; his The Tired Captains, published in 1928, draws on his experiences in the war and is well worth reading.

His great-niece, Mary Jo Hill Johnston, writes a blog about Curtis and was a major contributor to the Wikipedia entry on him. She has donated many of his papers to the University of Virginia.49

mrsmcq June 9, 2017

Notes

(For complete bibliographic entries, please consult the list of works and web pages cited.)

1 Curtis’s draft registration and 1922 passport application give his year of birth as 1891 (Ancestry.com, U.S., World War I Draft Registration Cards, 1917-1918, record for Marvin Kent Curtis; Ancestry.com, U.S. Passport Applications, 1795-1925, record for Marvin Kent Curtis). However, a genealogy of the Lewis family whose preface is dated July 15, 1891, gives his date of birth as October 10, 1890, and this is the generally accepted date (Lewis, Book VXIII. of the Genealogy of the Lewis Family, p. 42). His place of birth is taken from his draft registration and passport application; his date and place of death are taken from Wikipedia, “Kent Curtis.” The photo is taken from “Cruises in the Sun,” an entry in a blog by his great-niece, Mary Jo Johnston.

2 Wikipedia, “Kent Curtis.”

3 On his father’s occupation, see Ancestry.com, 1910 United States Federal Census, record for Charles E Curtis. On his college attendance, see p. 239 of Amherst Olio 1914 and “The Classes,” p. 218. In Fletcher and Young, Amherst College, p. 848, Curtis is listed among the class of 1914 “Non-Graduates.”

4 See Curtis’s draft registration.

5 Some of Curtis’s letters home were written on The Boundary Canoe Trips letterhead, which describes the program for the summer of 1917.

6 “Ground School Graduations [for August 25, 1917].”

7 Curtis, letter dated October 10, 1917.

8 Ibid, and letters of November 2, 1917, and June 10, 1918; War Birds, entry for October 3, 1917.

9 Hooper, Somewhere in France, letter of October 18, 1917; see also War Birds, entry for October 16, 1917; Deetjen, entry for October 18, 1917; and Foss, diary entry for October 14, 1917.

10 Hooper, Somewhere in France, letter of December 3, 1917.

11 Curtis, letter of November 21, 1917.

12 Hooper, Somewhere in France, letter of November 14, 1917; Foss, Diary, entry for November 15, 1917.

13 “Letter from Kent Curtis.”

14 Curtis, letter of December 20, 1917.

15 See The National Archives (United Kingdom), Royal Air Force officers’ service records 1918-1919, record for Marvin K. Curtis; and Curtis, letter of January 10, 1918.

16 See Curtis, letter of January 19, 1918.

16a Ira Jones, Tiger Squadron, p. 60.

16b Curtis, letter of January 19, 1918.

16c H. G. Clements, “Flying with 74,” p. 47.

17 Curtis, letters of October 31, November 2, 1917, and January 10 and 19, 1918.

18 The caricatures are in the notebook Curtis kept at Thetford starting November 20, 1917.

19 Curtis, letter of March 24, 1918; see also letter of April 9, 1918.

20 On 74’s preparations for departure, see Jones, King of Air Fighters, pp. 166-72. H. G. Clements names the restaurant in “Flying with 74,” p. 47.

21 Curtis, Pilot’s Flying Log Book, entry for April 8, 1918. Curtis omits the prefix letter. See Robertson, British Military Aircraft Serials 1878–1987, for C270.

22 Curtis, letter of April 28, 1918.

23 See Fry’s letter of March 29, 1918, quoted in “Lieutenant Clarence Horne Fry, R.F.C.,” and Curtis’s letter of May 3, 1918.

23a Jesse Campbell, diary entry for May 18, 1918.

24 Curtis, Pilot’s Flying Log Book, entries for June 11, 1918.

25 Cablegram 834-S recommends Curtis; 1303-R confirms making the appointment.

26 A copy of this memo from Dwyer is among Foss’s papers.

27 Curtis, letter of June 15, 1918, to his father.

28 Curtis, letter of June 23, 1918.

29 Curtis, Pilot’s Flying Log Book, entries for June 25–30, 1918. Curtis’s R.A.F. service record, cited above, erroneously indicates that on June 19, 1918, he went to No. 42 T.S. The next line of the record has him going from 63 T.S. to B.E.F. on July 4, 1918.

30 See Curtis’s R.A.F. service record cited above; the roster of officers on p. 61 of Taylor, A History of the 148th Aero Squadron; and Springs’s letter of July 18, 1918, to his stepmother (Spings, Letters from a War Bird, p. 181). The entries for July 4, 6, and 7, 1918, in the “Daily Report of Casualties and Changes 148th Aero Squadron” appended to Taylor’s history have Forster reporting on July 4, Curtis and Fulford on July 6, and Knox on July 7. Curtis’s letters of July 3 and 7, 1918, suggest he did not arrive at Capelle until the 5th or 6th.

31 Springs to his stepmother, July 18, 1918, (Springs, Letters from a War Bird, p. 182).

32 On Jenkinson’s and Clements’s roles, see Clements’s diary, entries for July 10 and August 1, 1918. On Jenkinson, see Mike O’Neal’s contributions to “Harry Jenkinson.”

32a Richardson, Pilot’s Log.

33 See Curtis’s Pilot’s Flying Log Book on the flights mentioned in this paragraph.

34 Curtis, letter of December 3, 1918.

35 Taylor, A History of the 148th Aero Squadron, p. 27.

36 Curtis, letter of August 2, 1918. 148 did have one victory to its credit; Kindley had downed a German plane on July 13, 1918, but Curtis may have been thinking of his own B flight. On Camels at this stage of the war, see Vaughan’s remarks on p. 174 of Springs, Letters from a War Bird.

37 Curtis, letter of August 13, 1918.

38 Curtis, letter of August 13, 1918.

39 Taylor, A History of the 148th Aero Squadron, p. 31.

40 Curtis, Pilot’s Flying Log Book.

40a Taylor, A History of the 148th Aero Squadron, p. 175.

40b Springs, Letters from a War Bird, p. 210.

41 Curtis, letter of September 15, 1918; Curtis’s informant for this rumor was probably Kenyon, who had become a prisoner of war on September 2, 1918, and whom Curtis mentions as his roommate at Karlsruhe (letter of October 6, 1918).

42 See, for example, “Latest Casualty List from Oversea Forces.”

42a Clapp, A History of the 17th Aero Squadron, pp. 41 and 75; Taylor and Irvin, Francis L. “Spike” Irvin’s War Diary and The History of the 148th Aero Squadron Aviation Section (p. 18 of the diary, p. 60 of the history); Springs, Letters from a War Bird, p. 253.

43 Presenting the Experiences, p. 64.

44 See Kenyon’s P.O.W. narrative on pp. 168-69 of “Presenting the Experiences”; Dennett, Prisoners of the Great War, pp. 97-98 and 107-08; and Messimer, Escape from Villingen, 1918, pp. 61-62.

44a Miller’s diary is in the archives of the Smithsonian’s National Air and Space Museum; I am grateful to archivist Elizabeth C. Borja for a photocopy of the relevant page.

45 Curtis, letter of December 3, 1918.

46 Curtis, letter of December 10, 1918.

47 Curtis, letter of December 24, 1918.

48 Curtis, letter of January 22, 1918, and undated cable.

49 “Kent Curtis Papers to UVA”