(Toledo, Ohio, August 31, 1893 – near Warlencourt, France, August 23, 1918) 1

Oxford, Grantham, Doncaster ✯ Scampton, Turnberry, Ayr ✯ France, No. 54 Squadron R.A.F. ✯ 17th Aero, Petite Synthe ✯ 17th Aero, Auxi-le-Château ✯ Epilogue

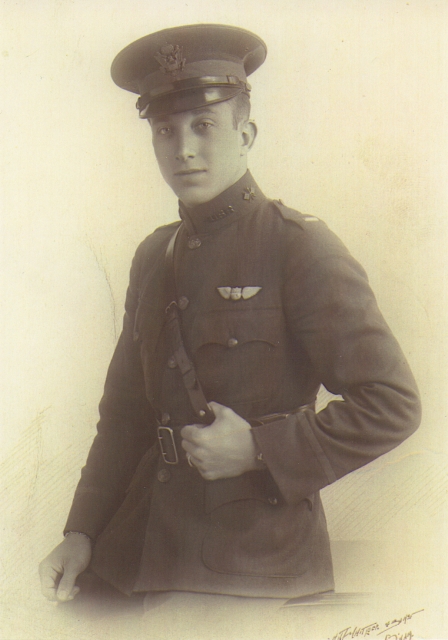

Campbell’s first name is frequently spelled “Merton,” but early reliable sources (including his draft registration with his signature) spell it “Murton.” It is perhaps a family name, although I have not been able to trace it as such. Campbell’s mother was born in England; his father’s family had lived in Ohio since the 1830s.2 He was in his third year at Ohio State University, studying mechanical engineering, when he registered for the draft in June of 1917, and he attended ground school there, graduating September 1, 1917.3

Along with most of his O.S.U. classmates, Campbell chose or was chosen for training in Italy. Like a number of his fellow cadets, he kept a diary, and the first entry, for September 6, 1917, announces jubilantly “ORDERS!! HOORAY!!” It was written “on the Penna. lines between Pittsburgh and Philadelphia on my way to New York. Twenty-three of No. [8] Squadron were ordered to N.Y. I expect we will all go to Italy. We will not only have a good trip but the experience will be fine. If any of us accidentally return, I guarantee that the time spent will not be regretted.”4 Campbell and most of his ground school classmates thus joined the 150 cadets of the “Italian” or “second Oxford detachment” who sailed to England on the Carmania. They departed New York for Halifax on September 18, 1917, and departed Halifax as part of a convoy for the Atlantic crossing on September 21, 1917. When the Carmania docked at Liverpool on October 2, 1917, the detachment learned to their initial consternation that they were not to go to Italy, but to remain in England and repeat ground school at the Royal Flying Corps’s No. 2 School of Military Aeronautics at Oxford. Campbell took the change of plans perhaps better than many of the other cadets, as remaining in England would give him the opportunity to become acquainted with his mother’s family.

Oxford, Grantham, Doncaster

At Oxford, Campbell roomed, initially in Christ Church College, with Allison Henderson Chapin, Charles William Harold Douglass, and Roland Hammond Ritter; he and Chapin in particular palled around together and double dated. When Chapin returned to college well after hours, Campbell and Douglass “put out a ladder over the wall for his benefit.”5

On November 3, 1917, Campbell and most of the rest of the detachment left Oxford to go to machine gun school at Harrowby Camp, near Grantham, where “we got an excellent reception. A band met us at the station, besides everyone along the way turned out.”6 The course was to be two weeks on the Vickers gun, and then two on the Lewis. However, after the first two weeks, it was determined that fifty of the cadets could go to training squadrons, and on November 19, 1917, Campbell (along with William Joseph Armstrong, Norman Kenneth Berry, Leonard Joseph Desson, Douglass, Weston Whitney Goodnow, Bradley Cleaver Lawton, Clair Rutherford Oberst, Earl William Sweeney, and George Herbert Zellers) set off for Doncaster in south Yorkshire where Nos. 41 and 49 Training Squadrons were located; Campbell, along with Desson, Lawton, Oberst, and Sweeney, was assigned to the 49th.7 He was delighted when on the day of their arrival “Flight Commander, Capt. Smith, gave us a joy ride. . . . I enjoyed it immensely and can truthfully say that I am not at all afraid of flying. We will learn entirely on M.F.S.H. [Maurice Farman Shorthorn] pushers.” Poor weather and a bad cold cut into his flying time, but on December 18, 1917, “I got my first real instruction this morning with Mr. Rounds. Was up 35 mins. Did only banks and turning but got on to it pretty well. He seemed quite pleased when we came down, but no more than I was. Heretofore, the weather has been so bumpy I could not understand the way he controlled the machine.” Two days later he “was ready for solo.” On December 20, 1917, he did a number of landings, most of them good, and then went for a “joy ride,” returning “filled with confidence.”

Scampton, Turnberry, Ayr

On December 28, 1917, Campbell was sent to the 45 Pool Squadron at South Carlton, as were second Oxford detachment members Desson, Douglass, Goodnow, Lloyd Andrews Hamilton, Lawton, Joseph Kirkbride Milnor, Hugh Douglas Stier, and Lynn Lemuel Stratton.7a From there Campbell went the next day to “the 81st Squadron at Scampton two miles further out in the country, making total of about five or six miles from Lincoln. The 81st is evidently a Pool Squadron, the same as the 45th.”7b He was soon joined by another second Oxford cadet, William Wyman Mathews, with whom he roomed. There they met Andrew Ortmayer, who had learned to fly in the States and was now serving as an instructor on Avros and, informally, as an advocate generally for the American cadets. There was more ground work to be done, and there were tests to be passed, but finally, on January 11, 1918, “had my first flight in an Avro and am very pleased with it.” Four days later Campbell’s instructor sent him off solo. William Thomas Clements, also at Scampton, but with No. 33 H.D. Squadron, wrote in his diary on January 17, 1918: “Camel [sic] was on his third solo and looped several times.” On January 25, 1918, Campbell made his first flight in a Sopwith Pup. The next day he wrote in his diary “I graduated in the R.F.C. today having done my last flip to complete my 25 hours.” This entitled him to four days graduation leave, but Campbell did not take them immediately, waiting instead until Wednesday, January 30, 1918, when he “Felt rather good this noon as I finished my 20 hours solo, making 2 on Rumpetys, 14 on Avros and 4 on Pups. Graduated as far as R.F.C. is concerned about Monday.” And with twenty hours solo he presumably also qualified as far as the American Air Service was concerned for his commission.7c He began his graduation leave that afternoon, setting out for Nottingham en route to the village of Bewdley, near Birmingham, where many members of his mother’s family lived.

Back at Scampton, on February 12, 1918, “had my first flip on a Camel this morning, but cannot say I am in love with the machine as yet”; he quickly learned about the torque of the machine’s rotary engine. He remarked on the 17th that “I am just beginning to learn how to do S.A. turns which is quite a job when it comes to a right one.” (A “split-arse turn” was a very tight turn.) The next day he received orders to proceed with Ortmayer and second Oxford detachment member Henry Bradley Frost to Turnberry in Scotland. There he ran into a number of men he knew, but only Elliott White Springs and Hamilton from the second Oxford detachment. From Turnberry Campbell went to Ayr on March 2, 1918, along with Frost and Ortmayer, as well as Reed Gresham Landis from the first Oxford detachment. He was astonished the next evening when he learned that he had received his commission and was, along with Frost, sworn in. 8

Campbell trained at Ayr through March 14, 1918, during a period when there were several fatal training crashes. His friend Andy Ortmayer crashed on March 7, 1918, and died the next day. “That was a blow to us all, as we loved and respected Andy more than words can tell.” Nevertheless, Campbell went on to write that “I have come to the conclusion that I will not let these things prevent me from flying. I am determined to fly that Camel in spite of Hell.”9 After the double funeral on March 12, 1918, for Ortmayer and Harry Glenn Velie (killed March 8, 1918, flying a Camel10), Campbell and his friend Joseph Ralph Sandford from the second Oxford detachment went out flying; Campbell was initially in an Avro, then in a “hedge hopping formation in a Camel. I felt much more at home in a Camel even tho’ it has a bad reputation.” Two days later, after some initial and to his mind inadequate instruction in aerial fighting, Campbell found that he, Sandford, and Hamilton from the second Oxford detachment, along with George Clarke Whiting and Errol Henry Zistel of the first, and Gustav Herman Kissel were to proceed overseas: “I did not like the idea on account of not finishing the course.”11 When Campbell reported to the R.F.C. in London on March 15,1918, Major General Charles Alexander Holcombe Longcroft, at that time overseeing the R.F.C.’s training division, “gave us a talk, on account of our being the first Americans attached to R.F.C. to go overseas.”

France and No. 54 Squadron R.A.F.

On March 19, 1918, after a couple of days at the pilots pool at Candas, Campbell arrived at No. 54 Squadron R.A.F., which was flying out of Flez aerodrome near Guizancourt, about twelve miles west of St. Quentin. He was glad to find that Sandford, who had been posted directly without having to kick up his heels at a pilots pool, was also at 54.

Campbell and Sandford had arrived just in time to experience the start of the Germans’ spring offensive on March 21, 1918. As new arrivals, they did not participate in patrols, but the frequent need to change aerodromes as the Germans advanced ensured that they became acquainted with the terrain and got flying experience. They moved initially to Champien, then Bertangles, then to Conteville-en-Ternois—where, to Campbell’s chagrin, late in the afternoon of April 4, 1918, he damaged a new Camel (D1783). Clouds having lifted, “the Major sent several of us up on show flips. I was in a Clerget which was a wonderful engine. I throttled it down to about 1050 to 1100 and S.A.’d around the drome without any trouble at all. But when I landed, ‘oh, horrors,’ I got down O.K. but was headed for a shell hole. I tried to turn which wrenched the under-carriage and over on my back. It was my first crash so have felt pretty bad over it ever since. The Major did not like it either.”11a Three days later, as the squadron moved yet again, this time to Chairmarais South near St. Omer, he had the misfortune to hit telegraph wires while landing at the new aerodrome in another new Camel (D6527): “Believe me, I was sure mad and peeved, but mostly chagrined, even tho’ it was really not my fault for going over. It was certainly tough luck.”11b

On April 12, 1918, Campbell wrote in his diary: “I went over the lines for the first time today at 8:00 A.M. Went on a high offensive patrol at 8–10,000 feet. We got archied like hell. The first I noticed was a big barrage directly in front of us, something like a formation of about 50 machines. Then they burst all around us so that we had to beat it out of the neighborhood. We were separated. I for one going my own direction, followed by two other machines. Only nine got back over Foret Nieppe. Sandy was missing so all I can see is that he was brought down by Archie or else got lost in Hunland or France.” Campbell went on two more patrols that day, including one in which he dropped two bombs and came back with “20 holes in my outfit.” On the April 17, 1918, he went out on an early morning patrol, flying Camel B2432; it was very misty, and he got separated from his formation. He eventually ended up well west of the lines: “I finally landed to find out where I was, and believe me, I sure was. I was right near Neufchatel and a good many miles from home. A civilian and a French aviator started me up and I got away O.K. But the worst came when my engine began to vibrate horribly and cut out. I landed all right but turned over in a ditch at Faviers [sic] just to the north of Le Crotoy about 2 miles. Hired a man to drive me to No. 6 Sq. which was in Crotoy. Capt. Duff wired my squadron and detailed some men to get my crash. We hauled it in this afternoon but that gang sure made a mess of the machine.” Campbell and his damaged plane did not get back to 54 until April 20, 1918: “I found that I had been posted ‘missing’ and my kit was inventoried, but am glad to say I am not missin’.”12

Once back at 54, Campbell participated in the unsuccessful effort to prevent the Germans from taking Kemmel Ridge. Soon thereafter the squadron learned they were “being sent on our much needed vacation. We will be with H.Q. and at the town of Caffiers.”13 May was spent playing baseball, dining and dating at Calais, and flying low over French beaches.

On June 1, 1918, vacation was over and the squadron was again stationed near St. Omer: “Work started in earnest today as we got orders for a line patrol from Ypres to Bailleul—dawn to dusk, with three machines. I was on the 3:30–5:15 patrol.” Campbell was put out that the squadron was soon ordered to move again. On June 11, 1918, they relocated to Vignacourt and were back in the vicinity of Amiens and Bertangles. While there Campbell was able to visit No. 3 Squadron R.A.F. at nearby Valheureux and see Hamilton and William Dolley Tipton (the latter was from the first Oxford detachment). The next day, June 16, 1918, No. 54 Squadron moved yet again, again back to the vicinity of St. Omer, to the aerodrome at Boisdingham. No. 20 Squadron R.A.F. was also there, and Campbell encountered Sweeney and Zellers.

With the 17th Aero Squadron at Petite Synthe

Campbell’s transfer out of 54 to an American squadron, which had been mooted since May 24, 1918, was confirmed soon after the move to Boisdingham. On June 20, 1918 he reported to the 17th Aero Squadron. “I hated to leave old 54 Sq. because I got so I tho’t I belonged to it entirely. I forgot I wore a different uniform. I liked the boys real well and I hope they did not hate me too much. Left after lunch and arrived at the 17th near Dunkerque, Petite Synthe Drome about 4 o’clock.” Frost was already at the 17th; they were soon joined by other members of the second Oxford detachment who had come in from R.A.F. squadrons: Armstrong, Desson, Dixon, Goodnow, Hamilton, and Lawton. The 17th flew Camels and, along with the 148th, was American in personnel, but stationed on the British Front and under the tactical command of the R.A.F.

The first days were spent getting their equipment pulled together. The day after his arrival, Campbell and six others went over to Marquise to pick up planes and fly them back, which they did without mishap; they returned in the afternoon, but bad weather forced them to overnight in Boulogne and come back by land the next day.14 By June 24, 1918, the men had been assigned to flights; Campbell was in A flight and deputy to flight commander Goodnow.15 On the 30th Campbell wrote: “Outside of lots of engine trouble and pressure pumps plus broken pipe lines, our busses in A are alright. . . . During the week we have had a little formation work and some on the target, but it is no small job to get a squadron organized.” Soon, however, they were flying regular dawn and dusk line patrols and, against regulations, crossing the lines; they had a confused encounter with German planes on July 7, 1918; a Fokker had Campbell briefly in his sights before being chased off by others from the 17th.16

Ten days later, Campbell began two weeks leave, which he spent in England visiting friends in Spalding and relatives in Bewdley and Erdington; he also took the opportunity to check in with his friend from training squadron days, Ronald John James Smith, who was at Hillington Hall in Norfolk recovering from an injury.

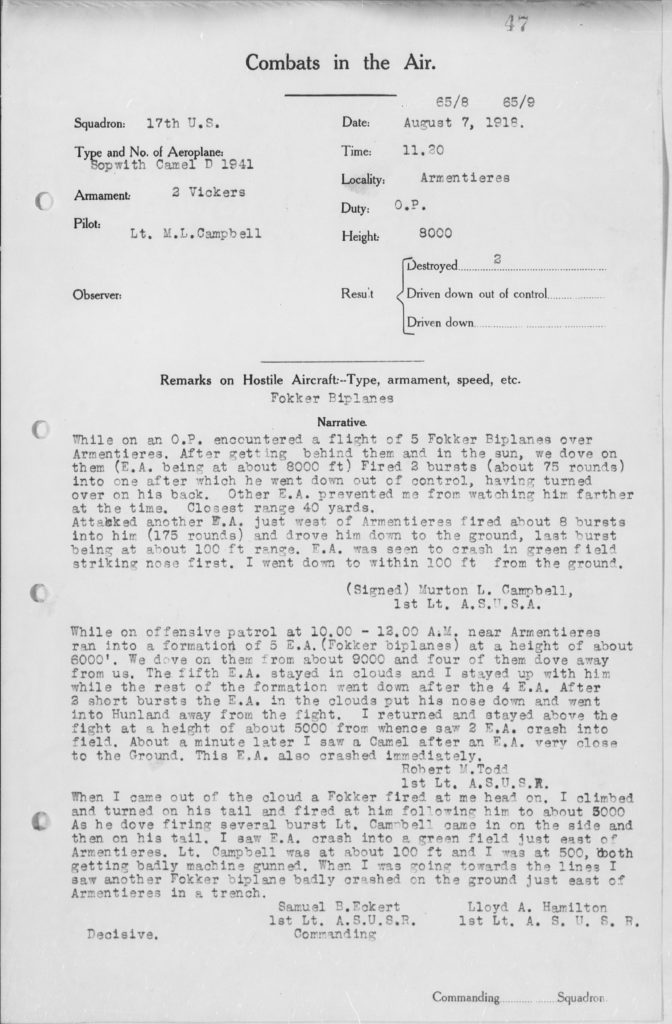

Campbell returned to France at the beginning of August; he wrote to a friend back home: “The night I arrived back in France they bombed the place where I stayed, Boulogne, and dropped a pill close enough to the hotel where I was staying to close the windows (swing type) of my room.”17 But he arrived safely back at Petite Synthe late in the morning of August 2, 1918. The next day he went out on an early morning offensive patrol. His flight encountered Fokkers near Roulers, and, when one tried to dive on him and Goodnow, Campbell, flying Camel C1627, downed his first enemy plane.18 Bad weather curtailed patrols the next few days, but on the 7th, Campbell, in Camel D1941 on an offensive patrol over Armentières, shot down two Fokker DVIIs.19

On August 11, 1918: “I went on my first bombing escort or rather cooperation this morning. I led the upper group of 3. We escorted 211 Sq. We went out to sea several miles to escape Archie, then came in over Holland and just this side of the wash and attacked Bruges from the east. We circled around the south of the city while the bombers went over the docks and dropped their pills. We only saw two or three Huns who were a little shy (I don’t blame them), as there were about 25 or 30 of us.” In the afternoon, he went out on an offensive patrol and that evening went to bed hoping for a good night’s sleep before the planned raid on Varsenare—which, however, was postponed because of poor weather: “Am rather disappointed as we wanted to get the thing over.”20

The raid came off on August 13, 1918. On that day, the 17th, along with several R.A.F. squadrons, targeted the German aerodrome at Varsenare. “I dropped my pills on the Fokker hangars, then shot up the machines and also the Chateau which was the object of much interest, as it was understood that the Hun C.O lived there. Forty Camels can surely play havoc with an airdrome.” Everyone returned safely and received warm congratulations.21 The men of the 17th were given the rest of the day off: “Went down to Calais for the afternoon to get away from camp and flying in general. A person feels rather relieved to get away and know that there is nothing else to be done during the day. I met Bill Mathews and we had a good afternoon together as is always the case when we get together.”

The next morning, Campbell “went on the bombing escort . . . at 10:30 and believe me we had a time too. Went overland and came in on Bruges from the S.W. Just before we got there the Huns jumped in upon us.” During the dogfight that followed, Campbell, again in Camel D1941, scored his fourth victory just before his guns jammed.22 As he tried to remedy the problem, enemy planes started firing at him, and he headed west, twisting and turning and losing height to shake them off. “Maybe I didn’t sweat blood those 20 odd minutes coming out of Hell. I expect the Fokkers tho’t I was going to crash when I got down to the ground but nothing like that in my family. I might have been scared but not sufficient to make me crash. The reprobates left me at the lines, being too poor sports to come over.”

The next evening (August 15, 1918), the 17th received word that it was to relocate the next morning, “but there was nothing doing, as we went on a 10:30 bombing raid over Bruges. Although there were a couple of Huns up overhead they did not attack, one of them being a monoplane, the Huns’ latest outfit.”23 However, on August 17, 1918, the pilots got up at 4 a.m. and began the move south to Auxi-le-Château. No. 54 Squadron had in the meantime been reassigned to Fienvillers, not far from Auxi, and on August 19, 1918, Campbell was able to visit men at his old R.A.F. squadron.

With the 17th Aero at Auxi-le-Château

On the 20th Campbell wrote that “we have been informed that the push is coming off tomorrow so we can be prepared for it.” The “push” was the effort to recapture Bapaume. The 17th was to escort R.A.F. bombers and, soon after their arrival at Auxi, to do low bombing and strafing themselves, as opposed to the high altitude patrols, which, with the exception of the raid on Varsenare, had been their fare at Petite Synthe.

Campbell again flew D1941 as part of a cooperative offensive patrol escorting R.E.8s the morning of August 21, 1918, and came close to claiming his fifth Fokker over Cambrai: “I got a Hun out of control but do not expect confirmation. The push has been a success so far according to reports and appearances.”24 He went out on another offensive patrol in the afternoon, and on the 22nd “escorted the R.E.8s again this morning and met the Huns as usual. . . .”

The next day, August 23, 1918, Campbell participated in the 17th’s first strafing sortie. Squadron historian Clapp describes the reason for the new tactic:

It was the nature of the fighting on the ground, while the Hun was going back, that worked so complete a change in our operations. The Air Force of the enemy was largely concentrated in the vicinity of Cambrai, but the congestion on the roads behind his lines gave us an opportunity of doing greater damage to his morale and material by attacks on moving infantry and transport, than we could ever have accomplished by devoting all our attention to his scouts. The latter, for the most part, flew in very large flocks and, except for sallies from time to time against small detached flights of Allied machines, they waged a defensive offensive. It was but natural, however, that they should make low-bombing and machine gun attacks on ground targets hazardous in the extreme.25

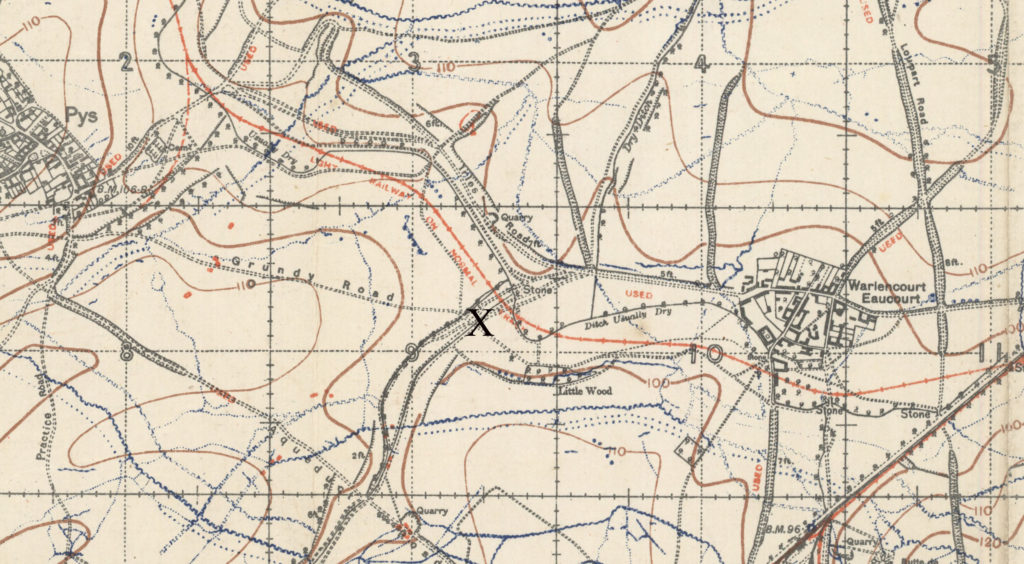

The raid in which Campbell participated with other A flight members Goodnow, Floyd Morrison Showalter, and George Thomas Wise was the first of five on August 23, 1918, and the only one of that day whose report Clapp failed to include in his history. Reed and Roland, in Camel Drivers, however, provide a description. The flight of four planes left at 11:30 a.m.; they initially targeted an ammunition dump near Combles, about six miles due south of Bapaume. Then they turned north and targeted transport on the road between Albert and Bapaume near Warlencourt. And it was near Warlencourt that Campbell, flying Camel D1941, was shot down, perhaps by ground fire, but probably by an enemy Fokker.26

Epilogue

Henry Robinson Clay, Jr., of the first Oxford detachment, who had been sent to France at the same time as Campbell, and was now with the 148th Aero, wrote in a letter to his parents on August 27, 1918, that “I lost one of my best friends of the [17th] squadron on a ground strafing stunt, Campbell was his name. He was one of the six who came out [to France] with me and a darn good friend of mine.”27

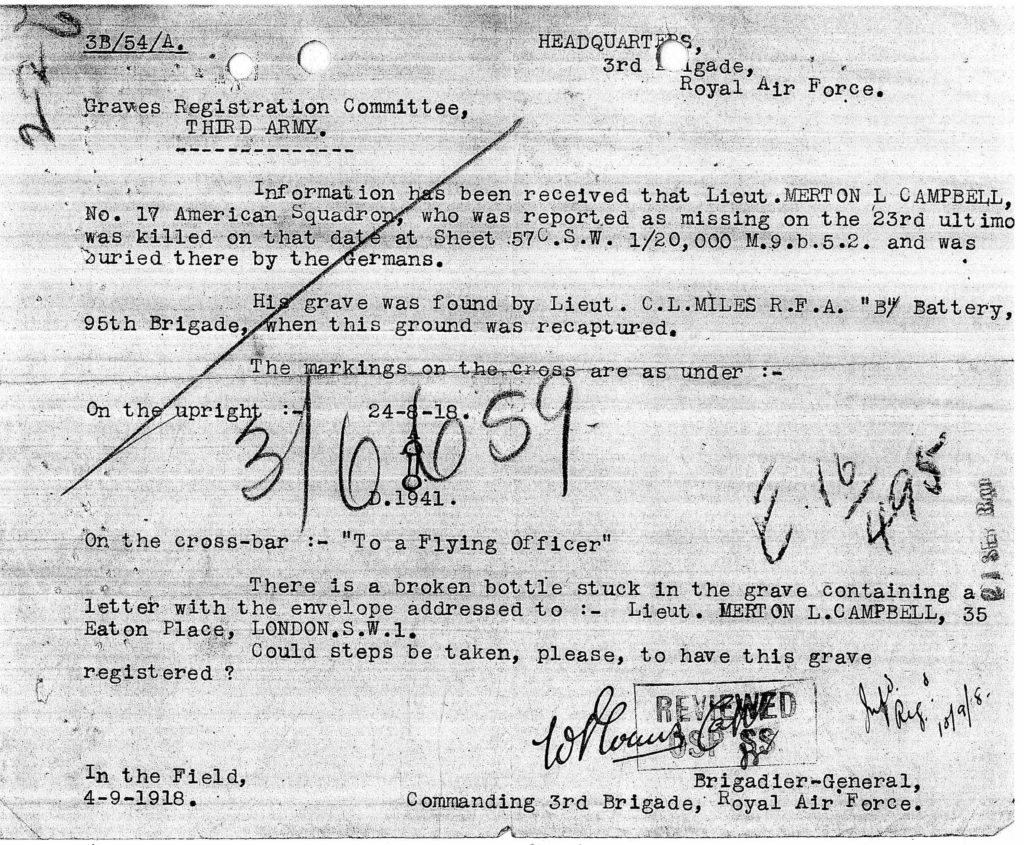

On September 4, 1918, a note was sent from the commander of III Brigade R.A.F.—to which the 17th was assigned—to the Third Army’s graves registration committee reporting that a Lt. C. L. Miles of the Royal Field Artillery had found Campbell’s grave, and requesting that the grave be registered.28

Clay wrote to his brother that “the other day some one found a grave of one of my best friends marked by a bottle with the envelope of a letter inside it—the bottle stuck in the ground. He came down a couple of miles behind the Hun lines and as they had time to put him away they did.”29

According to Clapp, he and other members of the 17th Aero sought out the grave and found that Campbell “had landed, upside down, in that broad belt of shell-torn country where there is not a yard not shattered by heavy explosive. His grave was a low soft mound beside his crashed machine. . . . We made a cross of a broken four-bladed ‘prop’ of fine mahogany that we got from salvage, and engraved a nameplate on a copper disk. We took it up past wrecked villages and then more wrecked villages, into the old No Man’s Land of some of the fiercest battles of the war. At the head of his grave without ceremony we set it up.”30

1st Lieut. Merton [sic] Llewellyn Campbell. On 13-8-18, Lieut. Campbell took part in an operation against Varssenaere aerodrome. He dropped 4 bombs from 200 feet on to some aeroplane hangars, which were afterwards observed to burst into flames. He then made several circuits of the aerodrome machine gunning huts, billets, E.A. on the ground and also the Headquarters of the aerodrome Staff, which was situated in the Chateau. On his way home, 20 miles over enemy country, he machine gunned, from ground level, several A. A. batteries. In addition this officer destroyed 2 E. A. on 7-8-18. These E. A. were observed to crash by other pilots, and Lieut. Campbell followed his 2nd victim down to 100 feet, although many miles the enemy’s side of the lines. On 3-8-18, he also destroyed 1 enemy machine. His dash and pluck are a splendid example to the rest of his squadron.34

The United States awarded him the Silver Star; the citation reads in part “First Lieutenant Campbell distinguished himself by gallantry in action while serving with the American Expeditionary Forces, in action near Varssenaere, Belgium, 13 August 1918, while on a patrol.”35

mrsmcq June 12, 2017; November 10, 201736

Notes

(For complete bibliographic entries, please consult the list of works and web pages cited.)

1 Campbell’s place and date of birth are taken from Ancestry.com, U.S., World War I Draft Registration Cards, 1917-1918, record for Murton Llewellyn Campbell. The photo is a detail from a group photo of Squadron 8 at the Ohio State University School of Military Aeronautics.

2 Information on his family is based on documents available at Ancestry.com.

3 See his draft registration cited above and “Ground School Graduations [for September 1, 1917].”

4 The whereabouts of Campbell’s original diary is currently unknown, but it was published in installments over the summer of 1930 in The Norwalk Reflector-Herald.

5 Murton Campbell, Diary, November 2, 1917.

6 Murton Campbell, Diary, November 3, 1917. Further quotations from his diary will be footnoted only when the date would otherwise not be evident. The account of Campbell’s activities during his training and active duty periods are based on his diary; his R.A.F. service record provides very little information.

7 Murton Campbell, Diary, November 19, 1917.

7a Murton Campbell, diary, December 28, 1917.

7b Murton Campbell, Diary, December 29, 1917. This was actually No. 81 Squadron, which was formed as a training unit and continued to serve as a training squadron rather than an operational squadron during World War I.

7c See here for R.F.C. graduation requirements. I have not found a document spelling out what was required of second Oxford detachment men to qualify for their commissions, but several of them indicated that they needed to have flown twenty hours solo. See, for example, Hooper, Somewhere in France, letters of December 28, 1917, January 31 and February 14, 1918; Milnor, diary entry for January 16, 1918; Deetjen, diary entry for February 14, 1918; see also, however, Clements, diary entry for March 9, 1918, when he had just over fourteen hours solo: “graduated by both R.F.C. qualifications and ours.” In practice, the men often fulfilled the twenty hours solo requirement at about the same time that they fullfilled the R.F.C. graduation requirements. While the consequences of R.F.C. graduation were immediate (graduation leave and then commencement of the next stage of training), commissions were often long delayed, presumably in part due to the logistics of distance (recommendations had to go from the squadron to London, to Pershing in France, to Washington and then back by the same route).

8 Pershing had recommended commissions for Campbell, Frost, Stier and Sweeney in a cable dated February 14, 1918 (602-S); the confirming cablegram was dated February 21, 1918 (821-R). It was typical that some days should elapse before the men were informed and sworn in.

9 Murton Campbell, Diary, March 9, 1918.

10 See “Velde [sic; sc. Velie], H.G.”

11 Murton Campbell, Diary, March 14, 1918. As it turned out, Zistel, whose commission had not come through, was replaced by Henry Robinson Clay (Campbell, Diary, March 15, 1918).

11a Murton Campbell, Diary, April 4, 1918; and see Sturtivant and Page, The Camel File, entry for D1783 (p. 112).

11b Murton Campbell, Diary, April 7, 1918, and entry for D6527 on p. 129 of Sturtivant and Page, The Camel File.

12 See Campbell’s diary entries for April 17 – 20, 1918, as well as the casualty book entry transcribed at Pentland’s Royal Flying Corps site (entry for Campbell in the “Surnames C-F” spreadsheet).

13 Murton Campbell, Diary, undated entry between April 25 and April 29, 1918.

14 Murton Campbell, diary entry for June 21, 1918.

15 Reed and Roland, Camel Drivers, p. 30.

16 See Campbell’s diary entry for July 7, 1918, and Reed and Roland, Camel Drivers, pp. 35-36.

17 “Murton Campbell’s Last Letters Home,” p. 15.

18 Murton Campbell, Diary, August 3, 1918; see his combat report on pp. 58-59 of Clapp, A History of the 17th Squadron. For his plane number, see Sturtivant and Page, The Camel File, entry for C1627, where the downed enemy aircraft is described as a Fokker DrI. Campbell’s combat report reports a “Fokker biplane.”

19 See Campbell’s combat report in Clapp, A History of the 17th Aero Squadron, pp. 60-61. Sturtivant and Page, The Camel File, entry for D1941 (p. 118) identify Campbell’s plane and the type of plane flown by his opponents; Campbell’s combat report lists “2 Fokker biplanes destroyed.”

20 Murton Campbell, Diary, August 12, 1918.

21 See Reed and Roland, Camel Drivers, Chapter 5, on the Varsenare raid.

22 See Clapp, A History of the 17th Squadron, p. 64, for Campbell’s combat report. Sturtivant and Page, The Camel File, entry for D1941 (p. 118) identify his plane and indicate that the enemy plane was a DVII.

23 Murton Campbell, Diary, August 16, 1918.

24 Murton Campbell, Diary, August 21, 1918; see his combat report on p. 68 of Clapp, A History of the 17th Squadron. Sturtivant and Page, The Camel File, entry for D1941 (p. 118), identify Campbell’s plane, noting “Fokker DVII D[riven] D[own] Cambrai.”

25 Clapp, A History of the 17th Squadron, p. 38.

26 See Reed and Roland, Camel Drivers, p. 70, as well as the entry in Henshaw, The Sky Their Battlefield II. Henshaw notes that there was a possible Camel claim in the relevant area by Carl-August von Schoenebeck.

27 Skelton and Williams, Lt. Henry R. Clay, p. 111.

28 Campbell, World War One Burial File; the location given is “57C SW 1/20,000–M.9.b.5.2.”

29 Skelton and Williams, Lt. Henry R. Clay, p. 120.

30 Clapp, A History of the 17th Squadron, p. 39.

31 Campbell, World War One Burial File. See Reed and Roland, Camel Drivers, p. 71, for a photo of the grave marker and the card sent by the American Red Cross to Campbell’s family. Most of the other graves from this cemetery were relocated in the 1920s to the Villers-Bretonneux Military Cemetery.

32 “Expect Aviator’s Body.”

33 Ford, Bert, “Five U.S. Airmen are Decorated.” And see Siebert, In the Camps and at the Front, p. 265, which suggests the award was announced on September 11, 1918.

34 “List of Honors and Awards, No. 1, Air Service, American E. F.,” pp. 7–8.

35 “Merton [sic] L. Campbell.”

36 Updated mainly to reflect information on planes numbers taken from Sturtivant and Page, The Camel File, with some additions from Campbell’s diary related to incidents on April 4, 7, and 17, 1918.