(Baltimore County, Maryland, September 5, 1892 – near the Château de Sorel, Picardy, France, June 10, 1918).1

Oxford ✯ Grantham ✯ Northolt ✯ London Colney ✯ Scotland ✯ London Colney again ✯ Turnberry ✯ Ayr ✯ Ferry pilot ✯ Beauvois ✯ Fouquerolles ✯ Epilogue ✯ Postscript.

Hooper’s first name was a family name; his mother was Margaret Parr before her marriage to Herbert Hooper in 1886. Margaret Parr’s father, the improbably named Israel Miltiades Parr, was the descendant of Quakers who had immigrated from Nottingham, England, in the late seventeenth century; he had become a wealthy Baltimore grain merchant. The Hoopers also were of English descent and started out in the sail-making business in Baltimore; they were related to old Maryland families such as the Bowens and the Sollerses. Parr Hooper was the youngest of three children and the only boy.2

Hooper attended Baltimore’s engineering high school, Baltimore Polytechnic, graduating in 1910.3 That fall he entered Cornell University’s Sibley College of Engineering. Among the subjects he studied was naval architecture, but he was also interested in flying and was a member of the Cornell Aero Club.4 After graduating in 1913 with a B.S. in mechanical engineering, he initially took a position at the Lanston Monotype Company in Philadelphia, but soon went to work for the New York Shipbuilding Corporation in Camden, New Jersey.5 He was at N.Y. Ship when the U.S. entered the war, and, despite his evident enthusiasm for things maritime, his fascination with aviation won out; he travelled down to Washington in June 1917 to apply for the Aviation Section of the Signal Corps. He was accepted—his education worked in his favor as did, presumably, his record as a cross-country runner at Cornell. By the end of June he was enrolled in ground school at the School of Military Aeronautics at Ohio State University and thoroughly enjoying the engineering aspect of the curriculum, but struggling with “buzzer” (mastering Morse code). He was one of a number of men from Maryland attending the O.S.U. S.M.A., and one of the sixteen who posed for a photo taken by Frederick Joseph Seligman that was published in the Baltimore Evening Sun on August 7, 1917, under the title “Maryland Boys to Fly in France.” At the time it was understood that the top graduates would go to France for advanced training. However, by the time Hooper’s Squadron 7 graduated from ground school on August 25, 1917, plans had changed, and he was among the eighteen men from this class at O.S.U. who had “put our names down for the Italian Front.”5a As he remarked in a letter home: “Everybody is getting very enthusiastic for Italy. All the jokes, remarks, & songs have shifted from French girls to Italian girls.”6

After a brief visit to Baltimore, Hooper reported to the aviation field at Mineola, Long Island, in early September 1917. Not being required to remain all the time at the field, he took the opportunity to visit his mother’s sister and her husband in New York and also spent an enjoyable weekend with his O.S.U. classmates Clarence Bernard Maloney and Charles Carvel Fleet at Fleet’s home in New Jersey. He spent some time and money getting properly outfitted: the right clothing, a watch, binoculars, and a camera—the last two he ended up not needing to purchase. He took his father’s opera glasses, and his friend Knud Sehested from N.Y. Ship made him a present of an Ansco vest-pocket size camera.7

On September 18, 1917, Hooper was among the 150 men of the self-styled “Italian detachment” who boarded the Carmania at New York. They sailed initially to Halifax where the Carmania joined a convoy that set out on the Atlantic crossing on September 21, 1917. The men were assigned to first-class cabins; Hooper roomed with Charles Heater.8 Much of the voyage was enjoyable and interesting, with Hooper getting to know his fellow detachment members, including “typical story-book Southerner,” Clarence Horne Fry.9 There were musical evenings, highlighted by the playing of violinist Albert Spalding, who happened to be on the Carmania. The only disagreeable part mentioned by Hooper was the Italian lessons conducted by Fiorello La Guardia, a “sane and a decent fellow at other times but in the class he is a mad man.”10 Once the Carmania reached dangerous waters, the men of the Italian detachment were organized into groups of ten who were posted to keep up a continuous lookout for submarines. Fortunately, they encountered no U-boats, and arrived safe at Liverpool on October 2, 1917.

Oxford, at the R.F.C. No. 2 School of Military Aeronautics

Almost immediately on docking, the men learned that plans had changed yet again and that they would not go on to Italy, but would remain in England and attend ground school (again) at the Royal Flying Corps’s No. 2 School of Military Aeronautics at Oxford University. There is a memorable passage in War Birds, apparently Elliott White Springs’s interpolation into John McGavock Grider’s diary, that records displeasure with the situation: “All our mail is in Italy, all our money is in lira and our letters of credit are drawn on banks in Rome and we’ve wasted two weeks studying Italian . . .”11 Hooper’s reaction was to send a postcard home giving his new address c/o the American Embassy, London, and reporting that “This country is going to be fine,” soon followed by a telegram: “Happy in England instead of Italy.”12

Hooper was among the ninety cadets (as they were now called) of the detachment who were assigned to Christ Church College (the others were at Queen’s). His roommates in Peckwater Quadrangle were Thomas John Herbert and Robert Thomas Palmer, both of whom had been at O.S.U. in the class behind Hooper.13 As instruction did not begin until Monday, October 8, 1917, there was time for recreation and exploring. Hooper and O.S.U. classmate Joseph Frederick Stillman went rowing on the Thames, and, along with another classmate, Joseph Kirkbride Milnor, made an outing to Blenheim Palace.14 Towards the close of an early letter Hooper remarked: “I am in love with England.”15

Although he mentions in passing that “the school is very good,” the content of Hooper’s classes is little mentioned in his letters home—beyond an enthusiastic description of a lecture on contact patrols. Instead he recounts invitations to tea at the home of Sir William and Lady Osler, whose hospitality both when they had lived in Baltimore and now in Oxford was well known and much appreciated. At the Oslers, Hooper met members of the Wright family, Canadian friends of the Oslers, now settled in Oxford, and was evidently much taken with one of the daughters.

He continued to enjoy rowing, and was also roped into cross-country races insisted upon by the commandant (presumably Bertram Richard White Beor) of the School of Military Aeronautics; in one instance, Hooper came in 4th of about 65. With Lynn Lemuel Stratton, another O.S.U. ground school classmate and rowing partner, Hooper was treated to a tour of the Bodleian conducted by librarian Sir Arthur Ernest Cowley. In the meantime the cadets had been subjected to an inspection “by a bunch of English and American nabob officers. They did not like our looks and now we all have to get tailored uniforms, swanky belts, little triangular caps that stick on one ear and in general have to spend more worry and money on our clothes than we do on our brains.”16 The men thus traded in their American campaign hats for R.F.C. caps and began wearing Sam Browne belts. It appears that Hooper did not take part in the shenanigans described so vividly in the War Birds entry for October 22, 1917, that led to the entire detachment being transferred to Exeter College, but notes that because of the move he nearly missed his engagement to “go see a girl I met at Lady Osler’s tea.”17

Rumors among the cadets were rife, the result, in part, of the uncertainty among the powers that were as to what would or could be done with the men. The number of planes and openings at training squadrons lagged far behind what was hoped for and promised. One of the more worrying rumors, from the twenty-five year old Hooper’s point of view, was one he recounted in his letter of October 27, 1917: “They are not taking any one over 23 years old for the scout fighters, so I probably will do bombing, photos or artillery work. Everybody put fighting down as first choice and there was great disappointment and surprise when they heard there was an age and weight limit.” He would learn that this, like the rumor that the men would return to the U.S. as instructors and the one about being ready for the front by January, was false.

Harrowby Camp, Grantham, machine gun school

A month after their arrival at Oxford, most of the cadets, including Parr, boarded a train that would take them to a machine gunnery school at Harrowby Camp, located northeast of Grantham (Lincolnshire) in the park belonging to Belton House.18 The cadets left behind “our old Sergeant [Elliott White] Springs and 19 other men to be sent to a flying school maybe Tuesday. Springs had a very important job and handled it very well. We gave him a handsome silver flask.”19

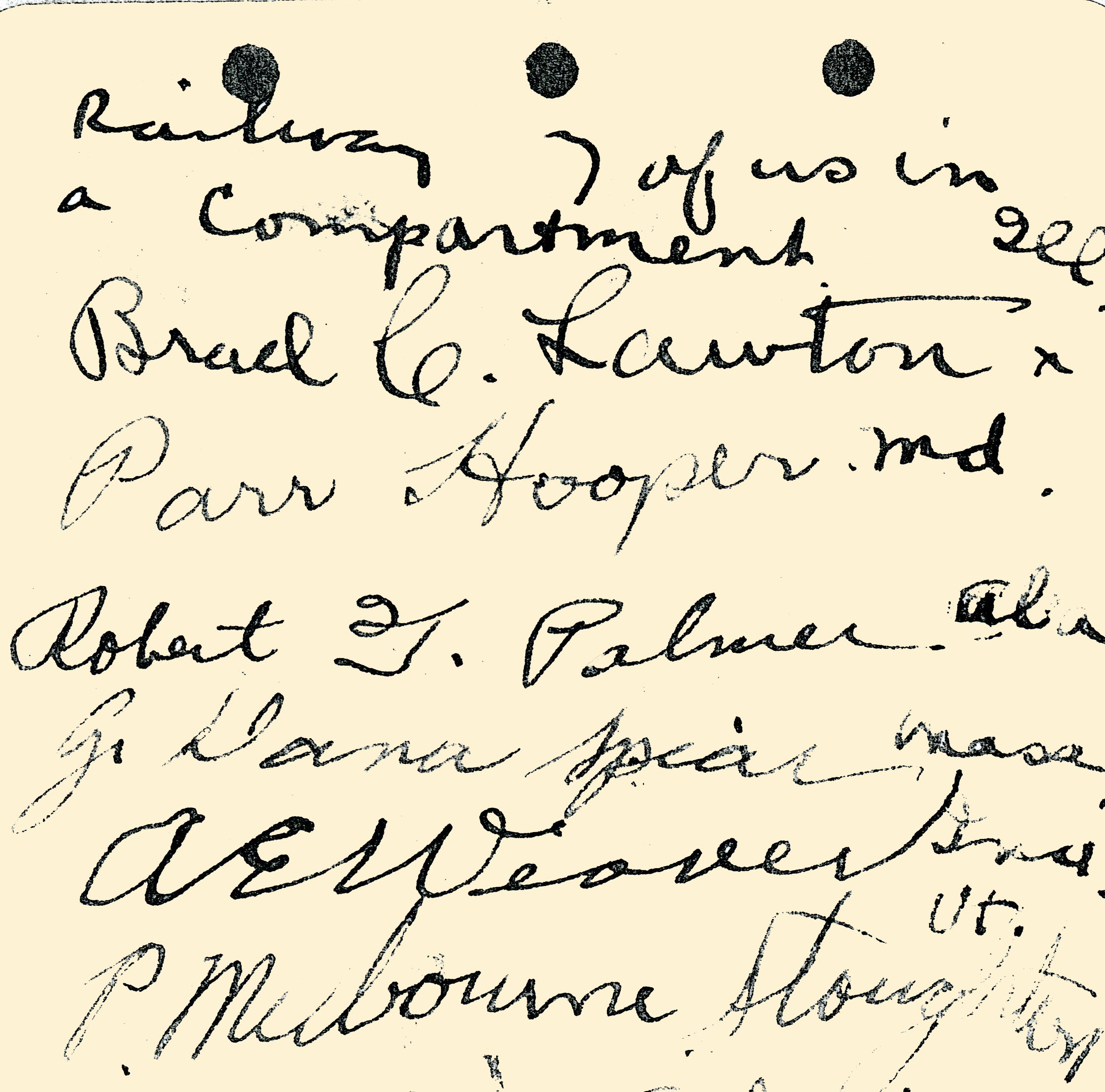

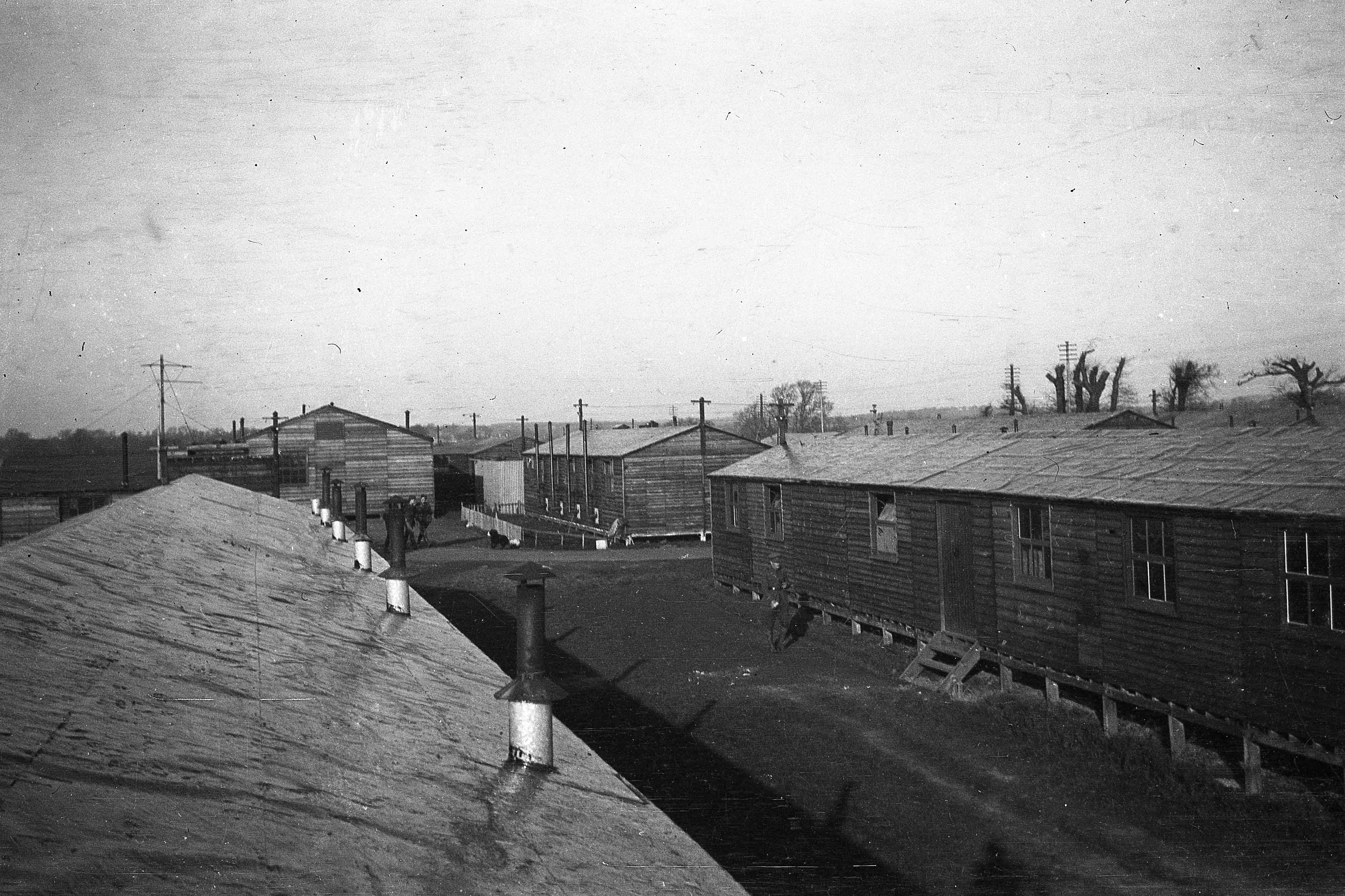

Fremont Cutler Foss, who was travelling to Grantham with Hooper, collected signatures from the men in their compartment, so we know they shared it with Bradley Cleaver Lawton, Palmer, George Dana Spear, Perley Melbourne Stoughton, and Albert Elston Weaver.20 It took about six hours to get from Oxford to Grantham, with an hour’s stop at Bletchley in Buckinghamshire. Hooper got out to stretch his legs and wandered into Sir Herbert Leon’s estate (Bletchley Park), with which he was most favorably impressed. On arrival at Grantham around 3:30 the men were welcomed with a band and music to which they marched to the camp. They were assigned to huts, “low long barracks buildings.” Hooper was bunking with men he “did not know very well before, and they are very fine fellows”: Lloyd Andrews Hamilton, Melville Folsom Webber, Henry Bradley Frost, Edward Addison Griffiths, and Harvard DeHart Castle, all of whom had been at ground school at M.I.T., graduating when Parr did, on August 25, 1917, and Thomas M. Nial and Edward Russell Moore, who had been at the University of Illinois, finishing up September 1, 1917.21

The morning after their arrival at Grantham, Hooper and Palmer went for a walk and viewed a nearby flying school, perhaps at Spitalgate or Harlaxton: “We saw some interesting machines and some good flying. It makes me feel pretty bad to watch the other fellow fly when I am so far away from it.”22 The rumor now was that “We will be here 4 months and then, it seems, will go to an aerial gunnery school. It looks like we got sent here because there was no other place to send us to—playing for time.”23 The latter was certainly true. The men were given a talk explaining, sort of, their status: “We are to be treated as officers. Have a regular officers’ mess, a man servant to each hut to clean up, make beds, shine shoes etc., and we do not salute anyone but majors and above. In other words we are mongrel—we wear half of officers regalia, are treated like officers, except are not saluted, but we are just cadets.”24

Despite his frustration at not being able to fly, Hooper made the best of machine gunnery. “Today we had the best training we have had here. The afternoon spent on the range. Each of us fired 80 shots. We made up a pool in our squad for each of the two tests and I won the first one, 9 shillings, for getting the best group. I got second in the other test of shooting at four groups of Germans painted on a landscape target. We went thru all the regulation motions of setting the sights on the proper range and the handling of the gun. It was great fun.”25 He confided to his parents (“Private for you and Mother only”) that “you may feel that I am a bit safer if I tell you that I did (so far as I could judge) the best shooting on the range out of the entire half of the detachment.”26 Hooper had been a promising member of Baltimore Polytechnic’s Marksmen’s Club, so his skill was not newly acquired.27

When not practicing or otherwise in class, Hooper explored the surrounding area, climbing the spiral stone steps of the steeple of St. Wulfram’s parish church in Grantham with Stratton and bicycling south with Palmer to Stoke Rochford Hall.28

Northolt, at No. 2 Training Squadron

Ten days after his arrival at Grantham, Hooper learned that fifty men had been selected to go to training squadrons. The next day, November 14, 1917, he learned that his name was on the list, along with those of his fellow O.S.U. classmates Stillman, Roland Hammond Ritter, and Guy Samuel King Wheeler. His initial information was that they, along with two men from the class behind them at O.S.U., Tommy Herbert and Dudley Hersey Mudge (“who I particularly admire”), would go to Doncaster. 29 In the event Hooper, Stillman, Ritter, and Mudge (but not Herbert or Wheeler), along with Edward Frank Hollander, Field Eugene Kindley, Walter Burnside Knox, Conrad Henry Matthiessen, Reuben Lee Paskill, and John Chadbourn Rorison, were assigned to Northolt aerodrome, located at Ruislip in northwest Greater London.30 Paskill was another O.S.U. classmate, and Hooper was also already good friends with Rorison from the class behind them.

Early the morning of Monday, November 19, 1917, Hooper, Stillman, Mudge, and Rorison caught the train to London, arriving at King’s Cross just before 11:00. They got lunch (allowed to spend only a limited amount due to war rationing, Hooper went away hungry) and did some sightseeing before setting out for Northolt. Once at the air field, they were assigned to Nos. 2 and 4 Training Squadrons (Hooper was in No. 2) and to huts. Hooper and Ritter shared one of the six rooms in their hut. The mess made up for lunch in London: “The mess is the most satisfactory I have struck yet.”31

Weather was initially “dud,” i.e., unsatisfactory for flying, and, since the men had one day off every two weeks, Hooper, Mudge, Ritter, and Stillman went into London the afternoon of November 21, 1917, for some shopping, followed by dinner at the Grill Room in the Piccadilly Hotel and a show, the long-running and very popular “Chu-Chin-Chow”—which left Hooper unimpressed.32

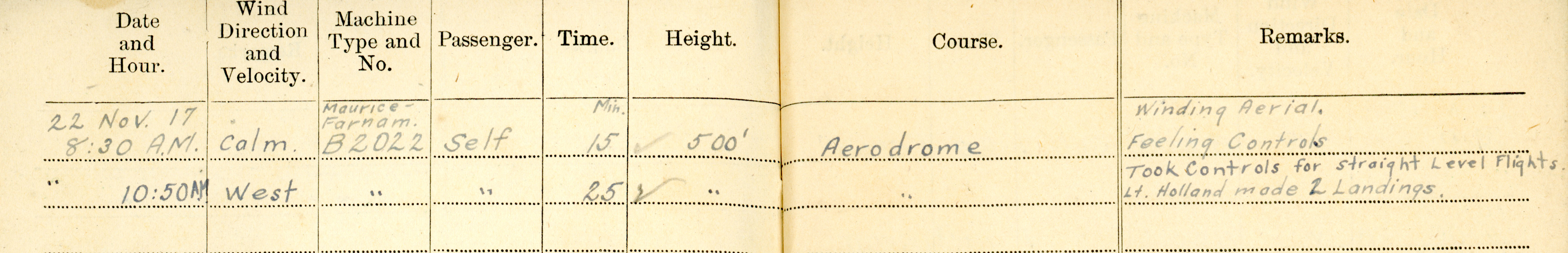

The next day, November 22, 1917, was “the most satisfactory day I have spent since I joined the army. And all just because of 40 minutes of the day. Forty minutes of flying. I have actually and at last done the thing, and proclaim it the king of sports. Before breakfast, Lieut. [William Ernest Bertram] Holland took me up for a 15 minute joy ride. I had my feet and hands on the controls but he did all the flying—I received the sensations.”33 Hooper recorded his first entry in his pilot’s flying log book: starting off at 8:30 a.m. as a passenger in Maurice Farman S.11 Shorthorn B2022 (a “Rumpty”), he was in the air for fifteen minutes. He got in another flight in the same plane, this time for twenty-five minutes, later in the morning.

Winter weather meant that opportunities to fly were somewhat curtailed, and the “one day off every two weeks” rule was evidently not enforced. Hooper went into London again on November 24, 1917. There was presumably a also special dispensation for Thanksgiving day (November 29, 1917), when Hooper was joined in London by Ritter and their new acquaintance, Canadian Bishop Wilson.34 Back at the air field, Hooper got in a little flying and otherwise spent his time waiting for good weather, socializing, and “going to boring classes and cleaning up hangars and machines.”35

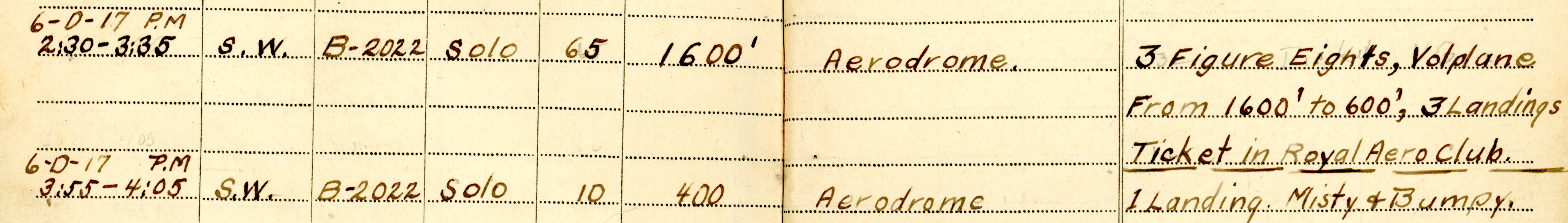

On December 4, 1917, after three days of no flying, Hooper was able to make five flights, the last one solo. “I want you all to rejoice with me today. I can fly! All by my little lonesome. I have had the most wonderful day. One of us Americans, Matheson [Matthiessen], did his 1st solo yesterday. I told my instructor about it and today he gave me an hour and five minutes instruction. Two flights before breakfast and one after breakfast. Then we ‘washed out’ (that is, stopped doing it and went away) because of the thick fog. After dinner the sun broke most of it away and he took me up and instructed me in the landings for forty minutes. Then he let me try it alone.”36 Hooper flew Maurice Farman S.11 Shorthorn B4698 for thirty-five minutes solo, with three practice landings, all described in great detail and much satisfaction in his letter home that evening.37 Two days later Hooper wrote and underlined “Ticket in Royal Aero Club” in his log book, meaning he had completed the requirements (figure eights, landings, specified altitude) to qualify for a certificate in the Royal Aero Club.

Although he was still in the early stages of training, this achievement evidently boosted his self-confidence: “Well I am all over the critical stage now. I can take an old bus up just as easily as riding [a bike]. I don’t do things just right all the time but I am safe. I have twenty minutes more to fly here and then I am ready and allowed to go to a scout squadron. However my instructor said that if I wanted to wait for my mate ‘Rit’ [Ritter] I could, and fly rumpties here as much as I please while waiting. Rit did his first solo today, and we only have to do 4 hours solo in rumpties before we go to the more advanced squadron, so I am figuring on staying here until we can both go together. It will be all the better for me because there is no better practice for ordinary flying than these unstable rumpties give.”38 Ritter apparently qualified the next day (December 7, 1917) and, according to his letter home that day, was going to get a photo taken as part of the formal requirements to join the Royal Aero Club.39 Hooper may have done the same. However, I find no record of either of their actual certificates—which, now that the R.F.C. was in charge of military pilot training, would in any case have been largely symbolic.

Hooper ended up waiting longer at Northolt than he had anticipated, for he was not posted to No. 56 Training Squadron at London Colney (about twelve miles north of Northolt) until December 18, 1917.40

In the meantime, he had by chance already become familiar with No. 56 T.S., having landed at London Colney on December 8, 1917, after getting lost in the fog, mildly embarrassed at having to ask where he was. Bad weather kept him at No. 56 T.S. from that Saturday through Tuesday, sharing a room with Albert Belding Gaines, Jr., an American who gave Hooper a tour of the aerodrome and showed him the machines. On returning to Northolt: “Everyone seemed glad to see me, and I was glad to get back. Lieut. Holland thought it was a nice experience for me, but said he had the wind up about me when it got dark the afternoon I left and before my phone message got back to him. He recommended me for scout machines.”41 Either the age limit had been lifted or had been only a rumor. Hooper got two days “posting leave” and went into London again on December 12, 1917, where he dined and went to the theater with Bishop and Ritter. They stayed the night, and the next day Hooper visited Mudge in an R.F.C. hospital. Mudge was recovering from a broken arm, the result of a crash on his first solo flight at Northolt.42 Hooper went into London yet again four days later and in the evening, with Bishop and Ritter, had dinner with the family of Canadian Reuben Alexander McLelland; the McLellands, and particularly their daughter Jean, became his good friends during his time in England.43

London Colney, at No. 56 Training Squadron

When Hooper arrived at London Colney again, this time officially, on December 18, 1917, he was pleased to find a number of other Americans at his training squadron, including his Oxford roommate Herbert, as well as Paskill from his O.S.U. ground school class. Francis Kinloch Read (“Frank”), who had enlisted in Washington the same day that he had, would shortly join them. Stillman was also posted to London Colney, but across the field at No. 74 T.S., as was Fry, the “story book Southerner.” Hooper’s roommate at London Colney was Charles Edward Brown, a second Oxford detachment member who had trained at the Princeton School of Military Aeronautics. “They say there are only 3 Avros (the dual controlled rotary engined machines we start our stunt training in) here. At that rate we will not fly very often. However the weather will not hinder us as much as it did when we were using ‘rumpties.’ This is a very good squadron—good instructors, good fellows as students, good mess, good huts, and pretty convenient to London. We walk about 3/4 miles, take a bus 3 miles to St. Albans, and there we have good train service to Town, the express going in in about 35 minutes.”44 In fact, weather did interfere with flying, and Hooper went up only three times before Christmas.

His first flight was in Avro 504j B4240 the day after his arrival at No. 56 T.S.; his instructor was William Jameson Cairnes. He did not get up again until December 23, 1917, this time with Bernard McEntegart, to do left turns and make two landings. On the twenty-fourth his instructor was the otherwise unidentified Lt. Pigott; they flew Avro B4237 and did five landings in bumpy weather. Hooper had two more brief flights before the end of the year: “The past week has been rather discouraging. Too many clouds, too much wind, and too many Americans arriving” he wrote on December 28, 1917, and then on January 8, 1918: “Flying has been very dud, and therefore life in general has dragged.” Bright spots had been Christmas and New Year’s Eve with the McLellands.

Poor weather continued into the third week of January 1918. The belated arrival of welcome Christmas packages, concerts, and dances at nearby St. Albans were the highlights of the period; Hooper also noted that Springs was now at London Colney. Hooper made his first solo flight in an Avro (C4481) on January 23, 1917. Then, the next day: “I have just finished the main part of a very wonderful day. I have had 45 minutes stunting instructions (dual), and 45 minutes practice (solo).” He initially went up with “Capt. Cairns [sic] showing me 1st stunts,” and then solo to practice “Loops, Immelmans, V.B.’s [vertical banks].” “Loops are the simplest thing you can imagine. It is great sport to stick your shoulders under the cockpit, swing to the safety belt, and hold on to the ‘stick’ for dear life and watch the earth roll all around you, up over your back, around your side, straight in front, any old way.”45

Hooper’s progress over the next three weeks was rapid. He practiced stunts, worked on formation flying with Cairnes, who also instructed him “in diving on others’ tails,” accumulated solo hours, and, on February 14, 1918, made his first solo flight on a Sopwith Pup (A6239): “Oh Boy! how she will climb, and what a feather touch you have to have on the joy stick. You pull her back an inch and zip you plunge up at 40°; push her forward 2 inches and you jump out of the seat to the safety belt and plunge down at 110 miles per hour. And the way she takes the curves—your wings are nearly in the vertical all the time. It almost flies itself.”46 He wrote his parents that “I have finished the required 20 hours solo and a successful flight on a real scout machine, and am recommended for my commission. I have done 21½ hours solo.”47

As though in retaliation for his success, the next day brought his first crash. In writing his parents he calls it a “rough landing” and goes on to describe how he “bumped my face against the padding put on the stern end of the machine gun for that purpose. It hardly seems possible for a boy 25 years old to be experiencing his first black eye, but I believe it is my first.”48 He noted, apropos a cross country flight to Northolt and back via Houslow, that “Landings are my weak point. I don’t seem to be able to hold her off until I lose flying speed.”49 Whether because he was shaken after his crash or because of bad weather, Hooper did not go up again until February 21, 1918, when, as he recorded in his log book, “Capt. Carns [sic] flew me to see if I had recovered from the crash.”

At the same time Hooper was downplaying his own crash in letters home, he was also putting the best face possible on the recent crash of his friend Stillman on February 8, 1918: “Fred Stillman met with a little bad luck and got burned a bit.”50 Hooper sought out his friend Francis Thomas Williams, a fellow Marylander and Hopkins M.D. now in London, hoping he could advise on the most modern burn treatment for Stillman. “If the authorities had let Frank take Fred Stillman into his hospital I am sure Fred would have gotten alright.”51 Stillman succumbed to his burns on February 23, 1918. “It was very sad because he was the best we brought over. He lingered for two weeks. I had my first experience at nursing with him. I stayed with him all the first night until he began to wonder if I was his death watch, and went to see him several times a day until his sisters and brother came.”52 A number of other second Oxford detachment men died in training crashes over the course of the spring, but Hooper does not mention any of them in his letters home, presumably so as not to cause his family worry.

Hooper continued to lead an active social life, taking advantage of his proximity to London. One evening he and his roommate Ted Brown were taking Jean McLelland to dinner at the Savoy and, running into Richmond Arthur Taber, of their detachment, and Harold Worth Vassar of the first Oxford detachment, “the four of us all entertained Jean at a fine supper.”53 Hooper had taken Jean McLelland to the Savoy a couple of weeks previously, on January 29, 1918, and experienced his first air raid. He also visited Marian Muriel Whiting and her family at their home, Long Acre, in West Ealing. Hooper’s older sister, Mary Bowen Hooper, had met Muriel Whiting in Norway in the summer of 1912 and had recently written Hooper with the Whitings’ address. William Henry Whiting, Muriel Whiting’s father, was a superintendent of construction in the Admiralty and thus a person who shared professional interests with Hooper. When Hooper learned that he would have four days “graduation leave” at the end of February, he turned to Mr. Whiting “to get some letters of introduction and some dope on how to visit the ship yards at Glasgow as I am planning to spend my 4 days doing that.”54

Graduation leave in Scotland

It turned out that Mr. Whiting’s son, William Robert Gerald Whiting, was submarine department yard manager at Armstrong Whitworth, a major British manufacturing company, at Elswick in Newcastle. Hooper’s first stop on his trip north was at Newcastle: “I saw Mr. Whiting’s son . . . and thru him got to see Armstrong’s Naval Yard, Swan and Hunter’s where the Mauretania was built, and Palmers where they build ships using iron ore as the start.”55 Hooper was evidently a young man who made friends easily: “The secretary of Swan and Hunter’s invited me to his home Monday evening. I had a very pleasant time sipping coffee before a grate fire talking to him, his wife, and charming daughter.”56 From Newcastle he went to Edinburgh where he played the tourist before going on to Glasgow. Mr. Whiting provided him with an introduction to William Joseph Luke, a director at the important Clydebank shipbuilding company, John Brown and Company, which had built the Lusitania and the Carmania and where one of Hooper’s Cornell professors, George Robert McDermott, had been a naval architect. The letter of introduction got Hooper a pass to visit the yard, which he did before actually looking up Mr. Luke in his office. The latter, it turned out, “had been to London the previous day, seen Mr. Whiting, been told about me, and told Mr. Whiting that I could not go through the yard because of a strict regulation barring aliens. I was asking him permission to go in alone and see more of the place and he was raving and calling up secretaries and gate keepers to give them a calling for letting me in.”57 Hooper “bickered in his office for half an hour but did not get to see any more of the yard, although I enjoyed the visit very much and learned considerable.”58 He also came away with some John Brown & Co. stationery, which he used for his first letter to his parents the day after his return to London Colney.

Back at London Colney

Poor weather meant little flying for the first week of March 1918, but by the end of the second “I have finished my training on Pups. Finally got to be able to put her on the ground without breaking her up. . . . Now I am flying Spads. It is a very heavy small wing surface, stationary engined bus. Makes 110 mi. per hour easily level, and dives like a bullet. 160 mi. per hour is as fast as I have put her into yet. It does not loop or Immelman well but rolls and spins beautifully. I like it more than any bus I have ever flown.”59

In the meantime, on March 4, 1918, Pershing had forwarded the recommendation for Hooper’s commission (along with those for Laurence Kingsley Callahan, John McGavock Grider, and others) to Washington; why it took from February 14 to March 4, 1918, for Hooper’s paperwork to go through is a mystery.60 Hooper rounded out his training at London Colney with practice firing a machine gun from his Spad at a target raft in Elstree Reservoir, about five miles south of London Colney, and with cross country formation flights with Herbert and Read: “Tommy Herbert led Frank Read and myself about 40 miles to his elementary training squadron one misty day. It was great sport because we all are very chummy and went on sort of a lark. Frank and l had almost no idea where we were. We could watch each other all the time. We followed old Herb like a dog’s tail and trusted he knew where he was going.”61 Hooper also took the opportunity one morning to fly over Ealing and give the Whitings a show in a Spad: “The first dive I made on the house brought them all out from the breakfast table waving their napkins. I played about for about 45 minutes, stalling dives, and slide slips down near to their garden, some rolls, and a nose spin. It seemed to amuse them very much, and I enjoyed it immensely.”62

Turnberry, at No. 2 Auxiliary School of Aerial Gunnery

On March 19, 1918, after a day’s leave in London, Hooper, Herbert, and Read set out at 8:50 a.m. on the twelve-hour train journey north to Turnberry on the west coast of Scotland, about forty miles southwest of Glasgow.63 During their week and a half there at the School of Aerial Gunnery they roomed together in what in peacetime was the Turnberry golf course hotel; their “window looks right out over the Firth of Clyde and Irish Sea,” and the accommodations in general were unexpectedly luxurious.64 They ran into a lot of men from the second Oxford detachment, including Ritter, “just finishing up here now.”65 “The course here is very well arranged, and the lectures and practices are very fine. We spend about 7 hours a day on the machine gun range. We have about 3 men using one gun and keep it pretty busy. The guns are arranged in aeroplane fuselages which are pivoted on a ball and socket joint. The regular aeroplane controls are all rigged to balance and point this fuselage just as though you were flying the bus in the air. We practice correcting gun stoppages and sighting on model aeroplanes set at various angles.”66 Hooper continued to excel in marksmanship: “I have been pointing the old gun pretty well. I made one perfect score on the 100 yd range with the model flying right angles to my line of sight, and the staff sargent seemed to think it was quite exceptional, saying that very few had ever been made. That was twenty shots all in the bull’s eye.”67

News of the German’s Spring Offensive reached the men at Turnberry—back in February Hooper had been aware that it was thought to be in the offing—“Have my doubts as to whether the Huns are going to stage their offensive. Don’t see why it is not on now if it is going to be”—but now it was a reality to be reckoned with.68

Ayr, at No. 1 School of Aerial Fighting

At the end of March, Hooper, Read, and Herbert went up the coast to Ayr, to the School of Aerial Fighting. They roomed at Carleton House, a few hundred feet from the shore and the Firth of Clyde.

From Carleton House they were bussed to the air field, situated on a racecourse slightly farther inland. Around the time he was posted to Ayr Hooper received word that his commission had been approved, but “I do not get lieut’s pay and do not wear the uniform until I get my active service orders which will come in perhaps a week.”69 “This lieut. dope has been drawn out and held up so long that it does not thrill a bit.”70 Nevertheless, being placed on active service on April 6, 1918, merited a telegram home, and not long thereafter Hooper had two formal portrait photos taken of himself in uniform at Studio Cecil in Ayr. Perhaps because the effects of his crash at London Colney were still apparent on his right side, the profile photo shows his left.

At Ayr, Hooper was initially “in the non flying pool . . . and will be for as long as the weather is dud,” a status he found frustrating.71 Nonetheless, he could report on April 3, 1918, that “I surely have had a wonderful day. Frank Read and I have been seeing Ayrshire on bikes.” In all, they put in forty-seven miles. The next morning Hooper and Tommy Herbert explored the coast to the south of Ayr on bikes. Two days later, Hooper was flying again, initially in an Avro near the aerodrome, but the next day in a Spad VII out over the water of the Firth of Clyde. He was flying A9142, a plane that he noted “did not have an air speed meter, altimeter, or engine temperature indicator.” He was nevertheless happy with it: “The rigging of the bus was fine, and I practiced some stunts. She half rolled beautifully. I never used to be able to tell just where I was or how I was doing the half roll, and did not come out of it correctly very often. But with this bus today everything seemed natural and easy.”72 Over the next days he alternately flew Avros and Spads, sometimes doing stunts, sometimes practicing formation flying. Finally, on April 16, 1918, he made his first flight on an S.E.5a (B660), “The type of scout that is doing so well in France now. It was not a particularly good one, not as tight and smooth mechanically as a Spad but very easy to fly although every time I tried to half roll it to the right she would full roll. The propeller torque is very strong and you have to account for it all the time. It makes a lot of difference whether your engine is off or on. She will hardly spin to the left, but goes around as fast as a Spad when nose spinning to the right.”73 A few days later he was able to fly S.E.5a D3433, which was “better than the first one I took up.”74 He was also pleased to be able to try out the “Hun Albatros” that happened to be at Ayr. This was Albatros D 1 391/16D, which had been flown by Lt. Büttner of Jasta 2 and forced down and captured on November 16, 1916. “It was a lot of fun. It flew so differently from our busses and was so roomy in the office. . . . It was very interesting to see where the Hun couldn’t see you.”75 Hooper made this flight just in time. His fellow second Oxford detachment member John L. C. Rorison, before leaving Ayr a few days later, took photos that show the Albatros, wings crumpled, after a crash.75a

Hooper remarked early in his time in Great Britain that “I am in love with England”; he also fell in love in Scotland. On April 17, 1918, “went to a wonderful party. . . . It seemed they needed some more dancers and as Americans are considered, over here, to be dancers I was invited along with three other Americans.”76 First Oxford detachment member George Augustus Vaughn was one of the other Americans invited.77 Among the higher, British, ranks was James Thomas Byford McCudden. Their host was Thomas Walker McIntyre, cofounder of Maclay and McIntyre, a Glasgow shipping firm; in 1907 he had purchased Sorn Castle, where the party was held. “We danced downstairs in the main hall on a floor that looked like they had been polishing it since Cromwell. . . . At the start the music was a gramophone, but pretty soon we brought down one of the numerous pianos, somebody produced a drum and cymbals and we had very clever music by several of the present talents.”78 The party, with food and champagne of pre-war quality and quantity, went on until 3:15 a.m., and during the course of it “I discovered a very interesting friend.”79 Hooper was evidently smitten with Alison, the youngest of the three McIntyre daughters. Over the next week or so, with air transport ready to hand, he made several trips to Sorn Castle, sometimes solo, and once with Frank Read as his passenger in an Avro. On April 26, 1918, having been invited to dinner, he made the trip more conventionally by bicycle.

That same day he had “finished all my training now, and am ready to try and do something.” He by now felt fairly comfortable in an S.E.5a, but, rather worryingly, “I still cannot land it properly. I have done in two undercarriages since I have been here.”80 While at Ayr, he had put in a total of thirty-one hours of flying time, all but one of them solo, with six and five hours on Spads and S.E.5a’s respectively.81

On Saturday, April 27, 1918, after joining in a vigorous game of baseball that pitted the American officers at Ayr against the American air mechanics, Hooper set out for Glasgow again, the first stop during seven days embarkation leave. He was sorry that Frank Read had not completed his training and could not go with him. With introductions from various Whiting family members Hooper was able to meet the family of Glasgow lawyer James Burns Kidston and to tour the William Denny and Brothers shipyard. He spent some time at the recently established American Soldiers’ Club in Glasgow, where he met “a very charming lady Mrs. Robinson [Robertson] Blackie who was Nell Botts of Savannah”—a distant relation of President Chester A. Arthur and “Aunt Nell” to songwriter Johnnie Mercer.82 After an expedition to Loch Lomond and up Ben Lomond, Hooper returned to Glasgow, where he looked up a Mr. Weir whom he had met at Sorn Castle; this led to a tour of D. & W. Henderson, another ship building firm. The next morning, May 3, 1918, “I got my telegram to report to Headquarters. I returned to Ayr and left that night for London.”83

Ferry pilot

Hooper arrived in London at 9 the morning of May 4, 1918, and late that afternoon ferried S.E.5a C6406 (“Viper SE”) from Kenley aerodrome south of London to Lympne on the south coast, a flight he described in his log book as his “1st Trip as a real war job.” He was painfully aware that he had “flown the first cousin to this bus only 5 3/4 hours”—the S.E.5a’s he had flown at Ayr presumably had been equipped with the predecessor to the Wolseley Viper engine that powered C6406—and that “Some of us have had pretty bad luck at this ferrying game,” so he flew this machine very gently.84 It was the machine flown four days later by James Ira Thomas “Taffy” Jones of No. 74 Squadron R.A.F. when he scored the first of his thirty-seven victories.85

Hooper spent the night of the May 4, 1918, at Lympne Castle (“I said Turnberry was war deluxe, so I am lacking a term for this because it goes Turnberry one better”86) and then returned to London. He and George Augustus Vaughn, who had left Ayr at the same time as Hooper, ferried planes from Brooklands to Lympne on May 6, 1918, and then, on May 7, 1918, Hooper ferried an S.E.5a to Marquise in France. He expected to fly across in formation with Paul Verdier Burwell and Vaughn, but they failed to link up with him, and he crossed the Channel on his own, “the first real compass course I ever steered. . . . There it was. France at last.”87 After dealing with paperwork at Marquise, Hooper spent a night at Boulogne before returning to London, where over the next few days he encountered a number of friends from the Oxford detachments who were either on their way to France or beginning ferrying duty (Charles William Harold Douglass, Herbert, Duerson Knight, Read, Ritter, and Paul Stuart Winslow).88 Hooper spent his last evening in England at the Whitings, and on Saturday morning, May 11, 1918, travelled to Folkstone and from there to France that afternoon.

With No. 32 Squadron R.A.F. at Beauvois in Pas de Calais

Many of the men posted to the B.E.F. and France kicked up their heels for days or weeks at a pilots pool, but Hooper learned on May 12, 1918, that he was posted to No. 32 Squadron R.A.F., and on May 13, 1918, he was at Beauvois, where the squadron was stationed, halfway between Hesdin and St. Pol.89 He was the first of only two men from the second Oxford detachment assigned to 32—Paskill would be posted there on July 16, 1918.90 However, at the same time that Hooper was assigned to No. 32 Squadron, two second Oxford detachment men, Douglass and Burr Watkins Leyson, were assigned to No. 73 Squadron R.A.F., a Camel squadron also at Beauvois.91 Another American, Bogart Rogers, had arrived at Beauvois and No. 32 Squadron on May 2, 1918, and Alvin Andrew Callender arrived there the day after Hooper.92 A few days later, Mathias Ellsworth De Zee, an American who, like Rogers and Callender, had received his initial training with the R.F.C. in Canada, was also assigned to No. 32 Squadron.93 The other pilots in No. 32 Squadron around this time included George Edgar Bruce Lawson from South Africa and Henry Clifford Leese from New Zealand as well numerous Canadians and men from Scotland, Ireland, and England.

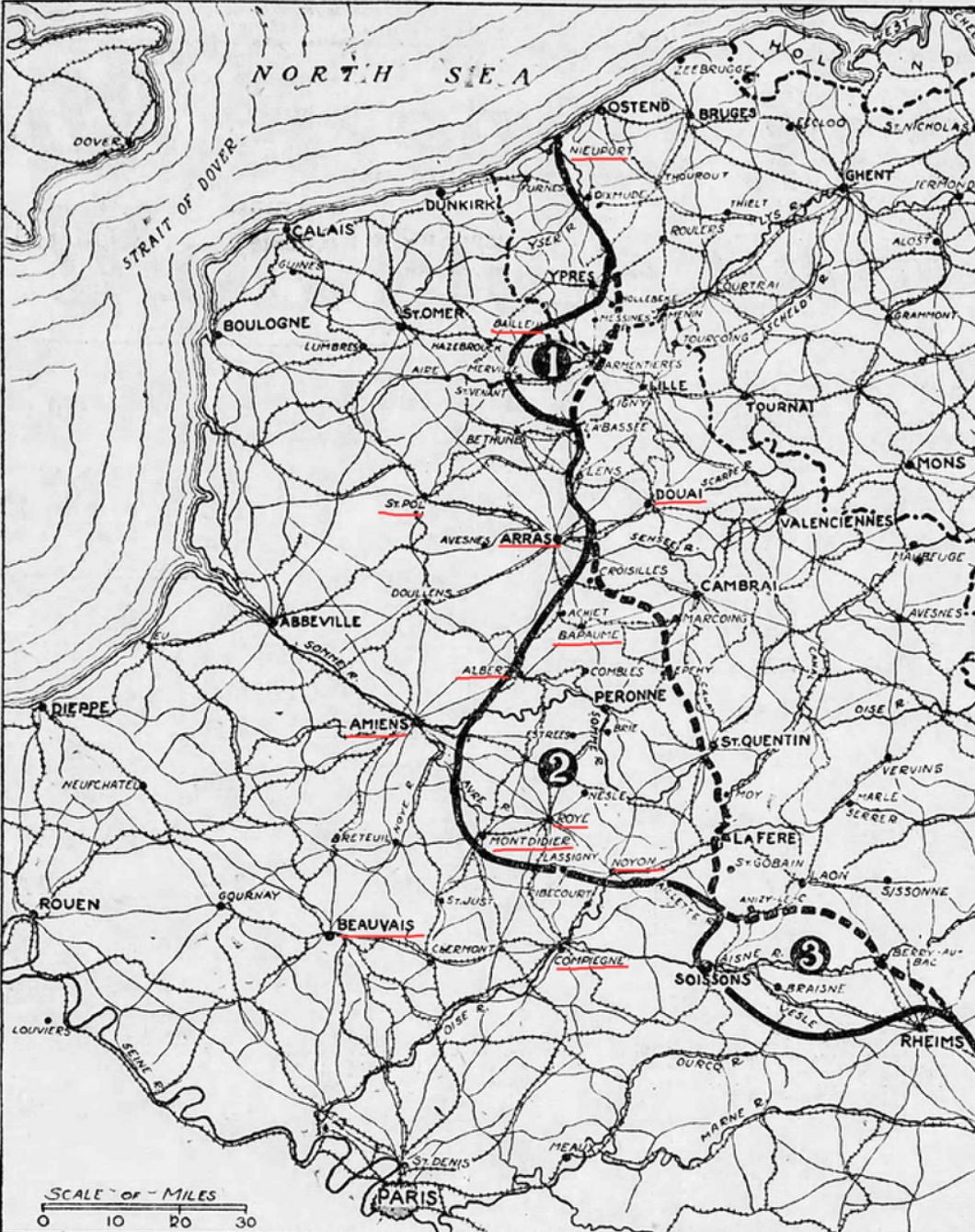

No. 32 Squadron had been formed in January 1916. It was initially commanded by Lionel Rees, whom Hooper knew as the C.O. of the School of Aerial Fighting at Ayr, and then by Thomas Algar Elliot Cairnes, brother of William Jameson Cairnes, Parr’s instructor at No. 56 Training Squadron at London Colney. From September 1917 until the end of the war No. 32 Squadron was under the command of John Canaan Russell. By March 1918 the squadron had exchanged its DH.5s for S.E.5a’s, and on March 26, 1918, it was reassigned from 11 (Army) Wing to 9 Wing, which became part of IX Brigade on April 1, 1918.94 Unlike other R.A.F. brigades, which were attached to particular British armies, IX Brigade served directly under R.A.F. headquarters in France and its squadrons could be sent wherever they were most needed. Around the time that No. 32 Squadron was transferred to 9 Wing, it (No. 32) was relocated from Bailleul (ten miles southwest of Ypres) to Beauvois (with a brief interim stop at Belleville Farm).95 From Beauvois, about twenty-five miles from the front, No. 32 Squadron flew line, offensive, and bomber escort patrols, or combinations thereof, over a wide swath of the front, from south of the Somme River to Nieuport on the Channel Coast, ninety miles to the north.96

Hooper was glad to be with a squadron that was flying S.E.5s: “They are using the type of machines I like the best.”97 The day after his arrival he took up S.E.5a B170, the plane he would fly most of the time, for a practice flight, “seeing the country” from St. Pol to Hesdin at 15,000 feet. Late the next morning (May 15, 1918), shortly after Callender took off on his first practice flight at Beauvois, Hooper set out again, flying a little higher and a little farther, and that afternoon, both Hooper and Callender took part in their first offensive patrol.98 This was apparently the only time during Hooper’s time with No. 32 Squadron that there were both enough pilots and enough functioning planes to make up a full complement of three flights of six pilots each—for ten minutes: Walter Alexander Tyrrell and Richard Thornley Hall “returned early with oil pressure trouble.”99 Hooper notes in his log book that the leader was Harold Charles Vizard, probably meaning Vizard was leading B flight, but possibly referring to the entire patrol.100 The route flown was triangular: southeast from Beauvois to Albert, then northeast over Bapaume to Douai, and finally west back to Beauvois: the approximately thirty miles from Albert to Douai were behind German lines.101 The record book notes that nineteen enemy scouts, i.e., single-seater fighter planes, were sighted southeast of Bapaume, but that they “dived East on approach of patrol.” That evening Hooper wrote home, remarking on the novelty of flying at 15,000 and 17,000 feet, as he had not flown above 9,000 feet during training.

Hooper participated in two patrols the next day, May 16, 1918, and this was generally the rule: a morning offensive patrol and a second one in the evening. On both patrols on the sixteenth the leader (presumably of B flight) was, according to Hooper, Edmond William Claude Gerard de Vere Pery, Viscount Glentworth, a pilot who had first been posted to No. 32 the previous autumn and who had been appointed a flight commander on May 6, 1918.102 In the morning the patrol flew northeast over Béthune to Bailleul—where No. 32 Squadron had been stationed until the end of March but which had fallen to the Germans in mid-April 1918. Flights of enemy aircraft (“Albitri”—probably Albatros D.5s) were sighted, as well as one or more two-seater enemy planes—Parr records having seen one of the latter flying at 20,000 feet (he notes his own altitude as 17,000 feet). A number of the pilots from No. 32 Squadron fired on the enemy planes over Bailleul, Estaires, and Warenton; all the “E.A.” escaped by diving east.103 During the same day’s evening patrol Hooper experienced his first “scrap.” East of Arras, the pilots of No. 32 encountered enemy planes and engaged them. Wilfrid Barratt Green was credited with destroying a Pfalz over Fresnes-lès-Montauban and Jerry Hope Laurice Wilfrid Flynn received credit for an Albatros D.5 driven down out of control south of Monchy-le-Preux.104 Hooper was able to confirm that Glentworth engaged the leader of a formation of enemy planes over Rémy (two and a half miles east-southeast of Monchy-le-Preux); it was lost to sight as it spiralled down, and Glentworth did not file a combat report to claim it.105 Writing home, Hooper was aware that his reaction times were slow: “The first scrap my leader and I went down with our engines full on and things happened so quickly that I did not even get my sights on anybody. . . . . In about two seconds the Huns had dived and spun down and my leader and the other mates that might have been following had disappeared in the mist.”106

Encounters with two-seater enemy planes during the morning patrol of May 17, 1918, noted in the squadron record book, receive no mention in Hooper’s log book, possibly because they did not involve his flight. Two pilots failed to return from this mission. Rogers wrote to his fiancée, “God knows where they are. Not a trace of them anywhere—nobody saw them leave the formation and they are simply gone.”107 It was later learned that Alwin Stewart Cross and Donald John Russell were prisoners of war.108 For Hooper the evening flight was memorable for a messy landing back at the aerodrome that resulted in some damage to the undercarriage and a wing spar of S.E.5a B170.

Hooper’s plane was quickly repaired, and he set out on an offensive patrol in it, according to his log book, at 8:40 the next morning, May 18, 1918. Hooper was one of twelve pilots assigned to this mission; Sumner Watson Graham and George Frederick Charles Caswell had temperature gauge and engine problems and had to return to the aerodrome; John Wallace Trusler, having lost his way, put down at No. 82 Squadron.109 The remaining pilots set a course for Douai, thirty-eight miles due east of Beauvois and about twelve miles inside enemy territory; they then, according to Hooper’s log book, turned towards “Villers” (presumably Villers-lez-Cagnicourt to the south). As early as 9:00 Arthur Claydon observed twelve enemy scouts patrolling at 18,000 feet east of Douai, and he and other pilots encountered and fired on formations of Albatros planes and pairs of two seaters, some of which were attacking R.E.8s and a DH.4.; the enemy planes escaped east. Lawson attacked a formation, and one of the planes got above him and fired into and disabled his engine.110 Over Etaing at 10:15 Hooper and Glentworth dived on and fired on a pair of two-seaters, which made off to the east. And then Hooper watched as pieces broke off Glentworth’s plane at 11,000 feet and as it went down in a spin.

Sturley Philip Simpson, Green, Claydon, Hooper, Flynn, Rogers, and Vizard landed back at Beauvois shortly before 11:00; Trusler found his way back to the aerodrome shortly before 6:00 that evening, and Lawson, who had made a forced landing northeast of Arras, also returned.111 All but one of the men in the initial patrol of twelve were accounted for. The handwritten squadron record book includes the following report: “1st Army A.A report an English scout thought to be an S.E5 fell out of control about H28 A 6.5. sheet 51B at 10.15 A.M. Owing to haze & sun were unable to see if machine fell in bits or crashed.”

The next day when Rogers wrote to his fiancée he promised to tell her in another letter “the strange tale of a chap we lost yesterday and what happened to him.” Neither here nor in the account in his letter of May 21, 1918, does Rogers provide a name, but he was evidently writing about Glentworth, who, “being a gentleman of some importance close inquiries were made from infantry and artillery. Finally someone was found who had seen the whole affair,” and who described an airman jumping out of his crashed plane and inadvertently running into a German outpost and being taken prisoner.112 How long this (comparatively) comforting intelligence was taken to be true is not known, but in late 1918 Rogers and C.O. Russell visited the site of Glentworth’s crash and temporary grave, some three miles southwest of Etaing, and a mile due south of the town of Vis-en-Artois, in whose cemetery Glentworth was later reburied.113

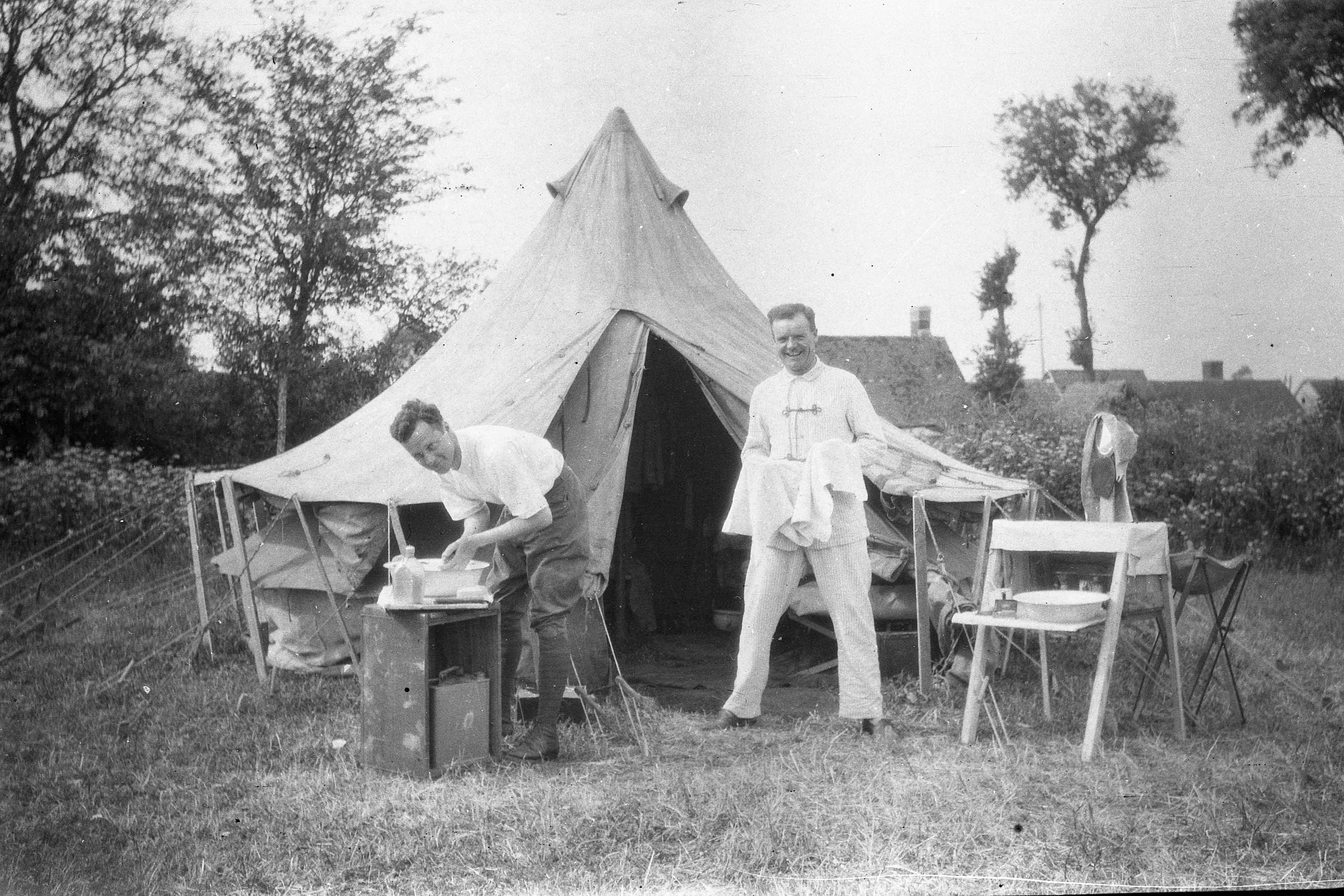

Hooper also wrote a letter home on May 21, 1918, and remarks that “The things I want to write about the censor will not like so my letter will be rather flat,” and it was perhaps concerns about censorship but probably also a desire to not to worry his parents unduly that kept him from mentioning Glentworth or the fact that there were now three of his squadron mates missing in action. Instead: “I have been on seven shows in Hunland. It surely is some life. Just the experience I have gained these past days has made me value it 100% more. I am having some times now that will be very valuable to look back on.” He goes on: “From 20 thousand feet the war is the most ridiculous performance you ever saw. You cannot see any human effort . . . and yet for hundreds of miles is this white scarred, pitted, and flooded piece of earth. Whole cities that are nothing but battered and heaped ruins, white and sandy and scarred, and a trail of smoke to leaward. Great forests that look like a burnt stubble swamp. And in all this sandy whiteness is the sheen of water in every rut. It’s all a mess and a disgrace to the human race but there is nothing to do but give it all the Hell we can now and repent when it is over.” Hooper gives a brief account of some of his fellow squadron members, including his roommate, Caswell. Hooper’s bunk had initially been in “part of the peaked roofed attic of an old French 2 story house” that Callender described as “set in the middle of an apple and peach orchard.”114 Hooper was much taken with one of the occupants of the cottage, evidently Caswell, “the greatest talker and the funniest fellow you ever saw . . . I have moved my bunk from the attic to a room in the first floor with the above character and as a result I am laughing nearly all the time.”115

The preceding two days, May 19 and 20, 1918, had been comparatively restful for the squadron; there was one offensive patrol the evening of May 19, 1918, in which Hooper did not take part, and otherwise only practice flying. Prior to writing his letter on May 21, 1918, however, Hooper had been on an uneventful early morning offensive patrol northeast to Armentières—some of it at 19,500 feet. Hooper notes that he has handled the “rarified air” well perhaps thanks to his cross country running. That evening, he flew his eighth offensive patrol and was fortunate to have avoided trouble. Rogers wrote that “three of us got into a nasty scrape and were very lucky to get out of it”—a trap set by a large formation of German planes had nearly worked.116 Hooper’s log book reads in part: “Bad Formation. . . . I left Capt. Clayton [sic] when I thought he was of another squadron. After 2:15 hrs. 40 Huns jumped what was left of us. I had just gone home.”

It is likely that a number of the missions flown by No. 32 Squadron from Beauvois were ones that involved escorting DH.4s on bombing missions (Nos. 25 and 27 Squadrons, both part of IX Wing and flying DH.4s, were based nearby), but it is only in Hooper’s log book entries for May 22 and 23, 1918, that such duty receives a mention. Apropos an early morning mission on May 22, 1918, to Nieuport and Ypres he writes “Escorted DH4 Home,” and the next day, at the end of patrol to Lens and “La Bassie,” “DH4 safe.”

Rain kept flying to a minimum from May 24 through May 26, 1918, and the missions Hooper flew on the 27th and 28th were uneventful. Because the engine in S.E.5a B170 was being replaced, Hooper did not take part in the evening patrol on May 28, 1918, when Callender, Simpson, and Claydon each claimed an enemy plane driven down out of control in the vicinity of Armentières.117 There was again no flying on May 29, 1918, and on May 30, 1918, B170 was still out of commission. However, “One of the fellows said I could fly his bus so I went up to the drome. However up there he changed his mind. We matched for it, and I lost. So I stood around as an interested spectator and watched the squadron leave.”118 Later that day he was ready “to go on a patrol but the bus I was to borrow had not gotten its undercarriage completely repaired from its last bad landing.”119 Finally, the morning of May 31, 1918, in a borrowed plane, B8374, usually flown by Tyrrell or Lawson, he was back in business, “but did not get close enough to shoot” while on a patrol at 18,000 feet over Douai.120 Hooper was beginning to get impatient: “I am beginning to get fed up on going up for 2 ½ hours and not getting any target practice. One of the fellows who came over from U.S. with us has gotten two Huns and will probably be a flight commander when he goes to one of our squadrons. So I have got to get a hump on” (Hooper was probably thinking of Lloyd Andrews Hamilton, who had been credited with two victories in April 1918).121 The evening of May 31, 1918, Hooper borrowed B331 and went “joy riding” with Callender to “ASD to see deserter Hun D.W.F,” taking in the coast as he made his way back from St. André-aux-Bois.

The last four offensive patrols flown by No. 32 Squadron out of Beauvois occurred on June 1 and 2, 1918; Hooper took part in the morning patrol on the first, and in both the morning and afternoon patrols on the second (on the last two he was flying B170 with its new engine). Enemy planes were sighted and fired upon by other squadron members, but Hooper’s frustration is evident from his log book entries: “No Huns,” “Saw 2 Albatross could not get to them,” and “Saw 3 Albatross but could not get near.” He also notes, chillingly, during the morning patrol over Amiens and the Somme at 18,000 feet on June 1, 1918, “Puisieux burning.”

With No. 32 Squadron at Fouquerolles in Picardy

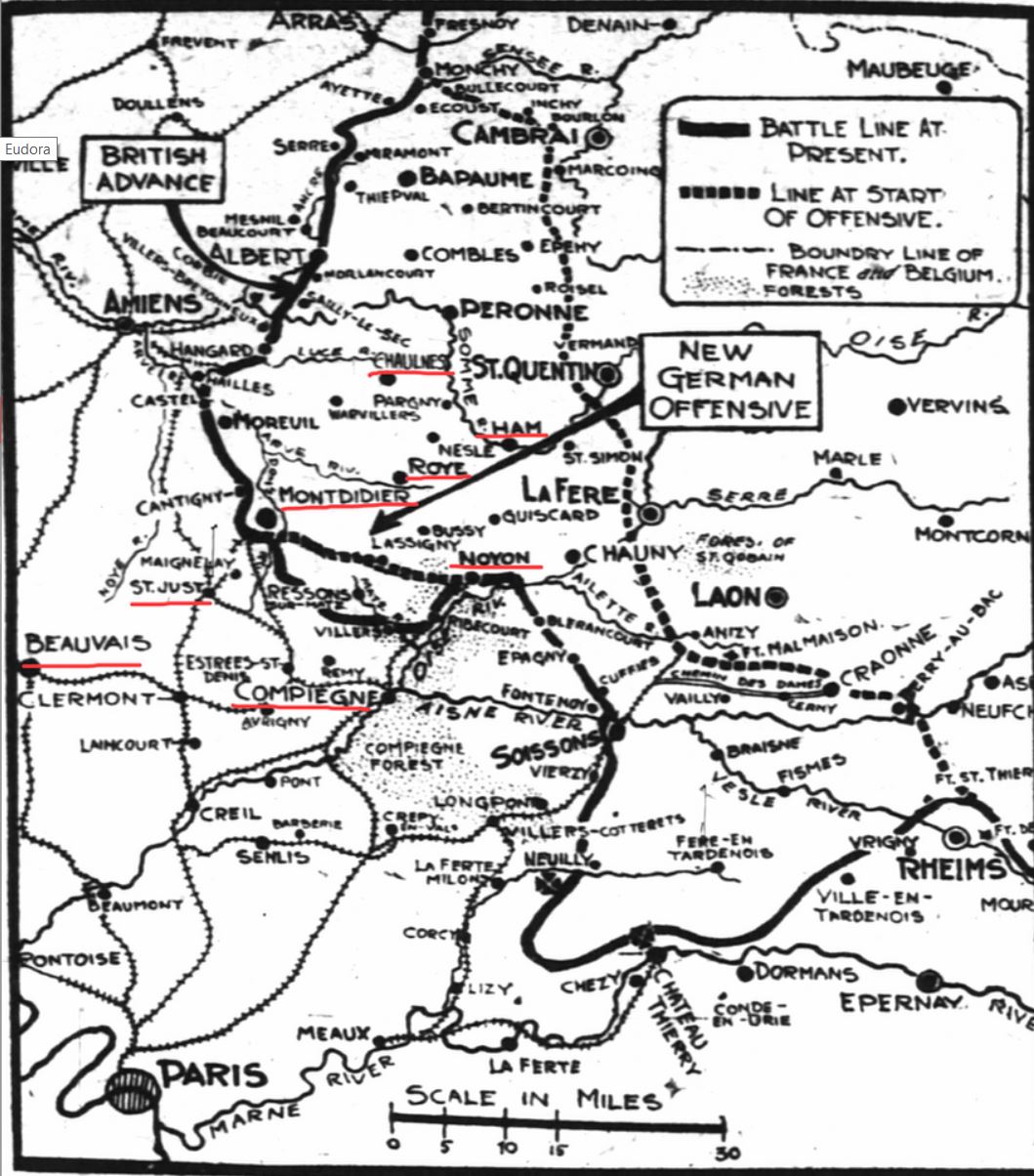

French and British leadership were aware at this time that a new German offensive was in preparation and that it would almost certainly take place on the French army front between Montdidier and Noyon with an attack in the direction of Compiègne. General Foch, on May 29, 1918, requested of the R.A.F. that five fighter and three bomber squadrons be prepared to move from the British front south to the vicinity of Beauvais behind the French front. On June 2, 1918, he requested that they make the move south as quickly as possible.122 Thus it was that No. 32 Squadron, along with seven other squadrons from IX Brigade, relocated on June 3, 1918. The pilots of No. 32 flew their planes approximately sixty miles due south from Beauvois to Fouquerolles, just east of Beauvais, arriving mid-morning after a flight of about an hour. Hooper, apparently like a number of other pilots, landed at the aerodrome there intended for No. 80 Squadron.123 Efforts to locate refreshment in Fouquerolles were not very successful, but “soon the C.O. car arrived. It was relieved of its load of recording officer, dogs, and C.O’s. luggage, and was used to take us to a fair sized town some 10 kilos away, in relays. We stayed there for lunch and dinner”—the town was evidently Beauvais.124 The next day Hooper flew his plane from No. 80’s aerodrome to that of No. 32, taking the opportunity to examine Beauvais further. There was general agreement that this part of France, the Oise region within Picardy, was particularly beautiful; food was plentiful, and sleeping in bell tents a welcome change from the old huts.125 Hooper continued to room with his friend Caswell.

The squadron flew its first patrol from Fouquerolles on the evening of June 4, 1918, “seeing the lines.” According to Hooper’s log book, they flew northeast to La Hérelle (about halfway to Montdidier), and from there flew southeast about twenty miles to Compiègne.

The next afternoon, Hooper took part in another, similar patrol, from Montdidier to Noyon: “Today in the patrol I was very much elated over having a streamer on my rudder. I was the rear guard (and top most)—the smell of the outfit as it were. Our flight, B flight, is coming into its own now. Our regular leader [Tyrrell] has come back from leave. He is an Irish boy about 20 years old, and some boy. He has gotten about 10 Huns. . . . He led us today for the first time.”126 Both on the fourth and the fifth, the patrols were flown at relatively low altitude, and Parr notes that “Our work has changed a little now, and I think it will be even more interesting. Instead of flying as a squadron away high up we are going out as flights and stay where you can see the ground.”127 In practice, these were the only low patrols flown by No. 32 Squadron until they began bombing and trench strafing on June 9, 1918. Until then they continued to fly high offensive patrols, evidently part of the effort to protect DH.4s and DH9s that were attacking concentrations of enemy troops in the vicinity of Roye, Chaulnes, and Ham, well within German-held territory, ahead of the anticipated German attack.128

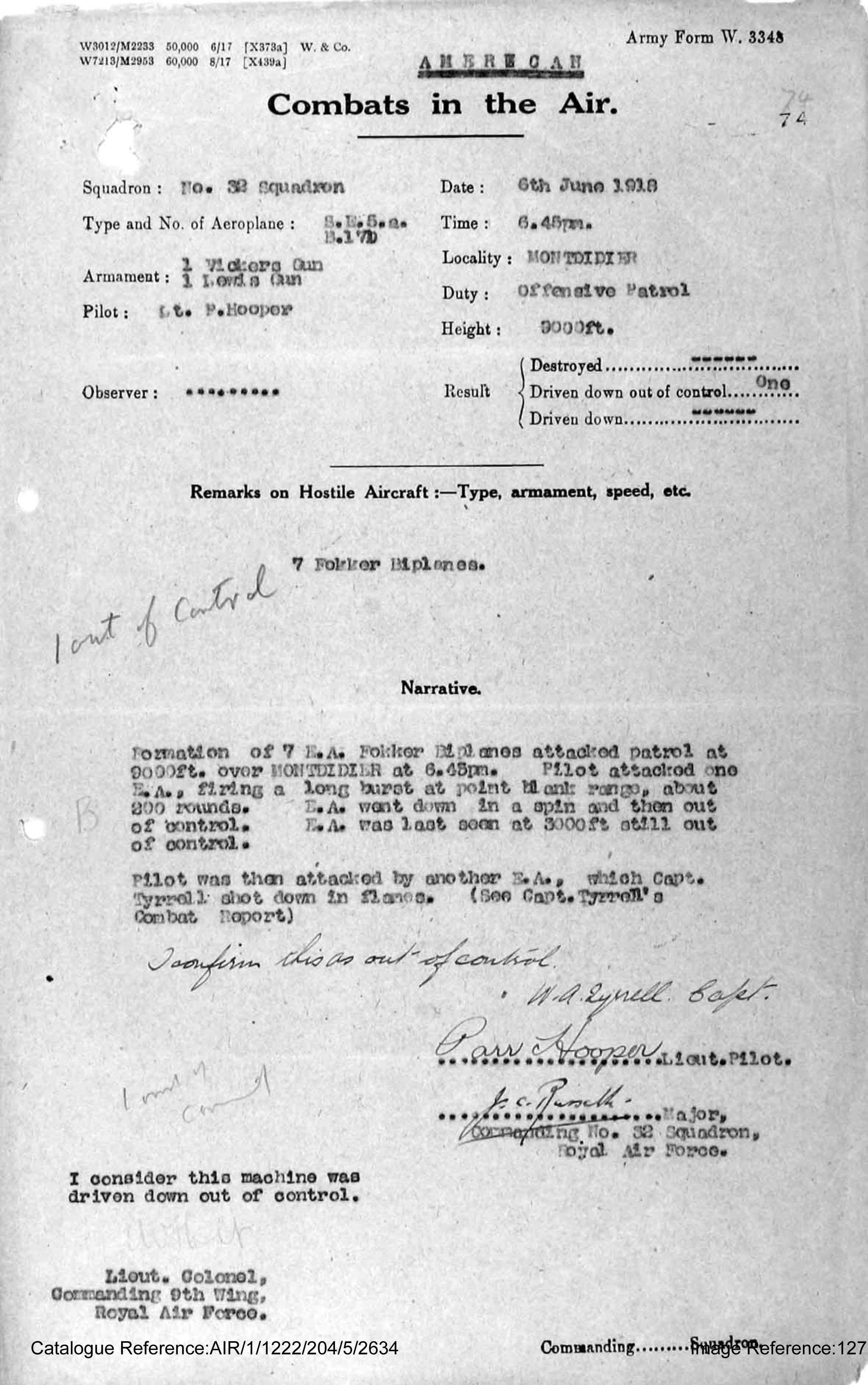

Hooper took part in an early morning offensive patrol at 12,000 feet on June 6, 1918, but was forced to turn back and land at Le Plessier-sur-Saint-Just, about eleven miles east-northeast of Fouquerolles, when a water pipe on his plane broke. He mended the break, had “a look at the lines alone,” and returned to the aerodrome shortly after noon. In compensation, that evening, on his nineteenth offensive patrol, he received credit for an enemy plane shot down out of control.129 It was, however, a near thing.

At 6:45 p.m. over Montdidier B flight had a “scrap with 7 Fokker biplanes New Hun scouts”—apparently Fokker DVIIs.130 Hooper, following close to Tyrrell, fired 200 rounds into a Fokker at point blank range; it “went down in a spin and then out of control . . . was last seen at 3000 ft. still out of control.”131 Hooper was then attacked by a Fokker, which Tyrrell shot down in flames before two more Fokkers attacked him (Tyrrell), who “turning . . . opened fire at close range,”132 sending an enemy plane spinning down out of control. Not long afterward, C flight, the upper formation of the patrol, along with three French Spads, attacked nine Fokker biplanes over Montdidier; Callender received credit for one enemy plane driven down out of control. All twelve of No. 32 Squadron’s planes returned safely from this mission, although Ralph Ellsworth Leet MacBean’s plane was damaged, Claydon’s guns had jammed, Russell (the C.O.) and Trusler had to return due to mechanical problems, and Hooper landed back at Beauvois with “engine dud. spars shot.”133 Hooper described the fight in a letter home: “We had some set to the other day. Four of us with other groups of mates just within sight, let seven new Hun scouts drop on us. It was some dog fight. We were all at close range and firing at each other from all angles. It is surprising how fast we seemed to go when we were charging nose on all guns and engine full out just grazing by each other at a relative speed of about 260 mi./hr. My flight commander shot down one who was on my tail, and also got another. I followed one down and got him spinning for a couple thousand feet. He would not break up but I thought he was done for and foolishly pulled out at 4,000 because we were pretty well over. From the looks of some of our own busses when we got back I got to thinking that perhaps the old Hun got to land almost safely after all.”134

The next day (June 7, 1918), on a late morning patrol Hooper flew S.E.5a D262. On the evening offensive patrol that day, according to the squadron record book, he flew D6867 (Hooper’s log book, for once, does not record his plane’s serial number). Both patrols involved encounters with enemy planes. Historian H. A. Jones notes that “On the 7th, in particular, there was enemy opposition, the bombers [of IX Brigade] . . . encountering formations of twenty-five to forty German fighters.”135 On the day’s first mission, the pilots of No. 32 Squadron’s A & B flights, patrolling from Noyon west to Montdidier around noon, dived on a formation of five enemy planes, both Albatros and Pfalz, firing numerous rounds, largely without result. Lawson, however, saw his target, an Albatros, fall on its back, drop down, and disappear; he was credited with one enemy aircraft driven down out of control.136 Hooper, for his part, was “flying last of 4, Tyrrel [sic] leading. . . . Dived on 5 feltz [sic] scouts at 9000 11:30; 11:50 dived to 2000 feet over 1st line trenches after a Feltz gave chase but no results.” The evening mission (5:00 to 7:10) appears to have been a bomber escort patrol and involved flying well over the lines to Guiscard and Villequier-Aumont.137 In the vicinity of Ham, pilots Claydon, Callender, and Simpson went after an Albatros and a Pfalz—Callender forced the latter to land in a field near Vendeuil—and had to leave it at that: “as he landed under control [and in German territory] I don’t get credit . . . .”138 Meanwhile, Tyrrell and Hooper pursued another enemy plane, without results. The squadron record book notes that “Patrol observed last formation of bombers being followed by six E.A., apparently 2 miles in the rear. Patrol dived for E.A. who immediately turned and made East at 6.25 PM.”

Hooper tried out his repaired B170, “testing new wing and engine,” the next afternoon (June 8, 1918). That evening, six planes from No. 32 flew an offensive patrol from Montdidier north-northwest to Moreuil, in conjunction with Camels, probably from No. 73 Squadron (thus probably including second Oxford detachment member Douglass).139 Hooper was leading MacBean and Arthur John Bateman, and following Leese, Rogers, and Lawson; they formed an upper formation over the six Camels. They saw a formation of enemy planes, which, however, headed east before they could engage them. On the return flight, the oil pipe on Hooper’s B170 broke and he was forced to land in a field about a mile and a half south of the aerodrome. He described his experience in a letter home the next day: “I had my first taste of a deputy leadership the other day. Six of us went out in two groups of three, and I led the top rear group. It is a lot more fun than following, and gives you a much better chance to see what you want to. I got them back to within sight of the airdrome when my engine conked and I put her down in a field. I have had a couple of forced landings here in France, and have a terrible time getting someone to talk French over the phone for me.”

In the same letter (June 9, 1918), aware of how long it would be before his parents would receive the letter, Hooper wrote “I suppose you have read weeks ago about the push the Hun started this morning. I was routed out at 4.30 and had my first taste of the low stuff.” The German attack had begun well before dawn.140 The planes of IX Brigade, whether bombers or scouts, were employed in what the 32 Squadron record book labeled “special missions,” low-flying bombing and strafing, extraordinarily dangerous work that exposed them to ground artillery fire as well as the defensive attacks of German planes. Additionally, according to Hooper, “There was a very heavy ground mist over 75% of the ground and generally misty all up to 3,000. We could hardly tell where the lines were.”141

Hooper was flying C9626, previously flown by Simpson, who was going on leave, and was one of six pilots in this first wave of scout bombers that set off at 4:30 to bomb and strafe between Montdidier and Lassigny at 2000 feet.142 “After we got over the lines I made my first spiraling dive and I never saw my mate [MacBean] again until the end of the show. It was some show too. Believe me I was glad I was a pilot and not down in that mess. It just so happened that my mate and I were the only ones of the first party of six to come directly back, although all the rest were eventually heard from or returned.”143 The 32 squadron record book lists Hooper, MacBean, Claydon, Hall, Graham, and Callender starting at 4:30 a.m. on June 9, 1918, with MacBean and Hooper returning together at 5:55, having dropped bombs on Remaugies and Conchy.144 Callender did not return until noon, having had to replace a broken propeller after landing east of Clermont (Oise).145 Claydon and Hall, after dropping bombs near Piennes and on Montdidier, landed at Epineuse at 7 a.m. to refuel before returning to the aerodrome, arriving at 8:30 a.m.146 Hooper noted in his log book who had “not returned,” crossing out Claydon and Hall when they got back and noting that Graham had been wounded. He also kept track of the second wave of special mission pilots who set out at 6:00 a.m., and Tyrrell’s name among the “not returned” is not crossed out. Hooper’s flight commander, after dropping three bombs on enemy troops at Roye, was, according to the squadron record book, observed by Leese “to nose dive into the ground from 1000 feet. It is assumed that he had fainted in the air as a result of wounds. The machine caught fire, and it is reported that the pilot was burnt to death.” Hooper is silent on this loss when writing home.

Not long after Callender’s noon return, he, Hooper, and Lawson took off again. The record book labels this a “special mission,” although it appears to have been a standard high offensive patrol, albeit with only three planes, flown, according to Hooper’s log book, at 17,000 feet. They “tried to get to Hun reported to be over Compiegne at 2000 [sic; sc. 20,000?]. Callendar, Lawson, & I. Saw three at about 22000 could not climb up. I did not have on flying clothes. Saw towns & Hospitals burning.”

Pilots from No. 32 Squadron flew one more low bombing and strafing mission on June 9, 1918, setting out around 7:00 p.m.147 Nine planes took off, but a broken wind screen forced Vizard to return early. The remaining pilots dropped two twenty-five pound bombs each and fired on troops and transport; all returned without mishap. Hooper’s log book entry—written in the hasty cursive characteristic of these late entries—reads: “Trench strafing. I was following major Russell Montdiddier [sic] & Conchy; machine guns & 2 bombs. Home in rain. Big war, transports, fires, shells.” The record book specifies that he dropped the bombs “from 1500 feet on transport in Orvillers-Sorel at 7.20 PM” and that he “Fired 550 rounds at transport on roads in vicinity of Orvillers-Sorel” (about eight miles southeast of Montdidier) before arriving back at the aerodrome just after 8:00 p.m. At 10:00 he wrote his parents an uncharacteristically short but cheerful note.

The next morning, just after 4:00, six pilots, working in teams of three, set out to target the same general area around Orvillers-Sorel. Leese, Lawson, and Rogers dropped their bombs and strafed troops and transport around Cuvilly and Mortemer before returning shortly before 6:00. Rogers noted “Seven E.A. Scouts patrolling area at 8000 feet.”148 Trusler and Bateman, having dropped bombs and attacked troops near Conchy-les-Pots, arrived back at Fouquerolles at 6:25. They reported having seen “Lt. Hooper spiral down and crash near Sorel-Chateau at 5.15 AM (Approx.).”149

Epilogue

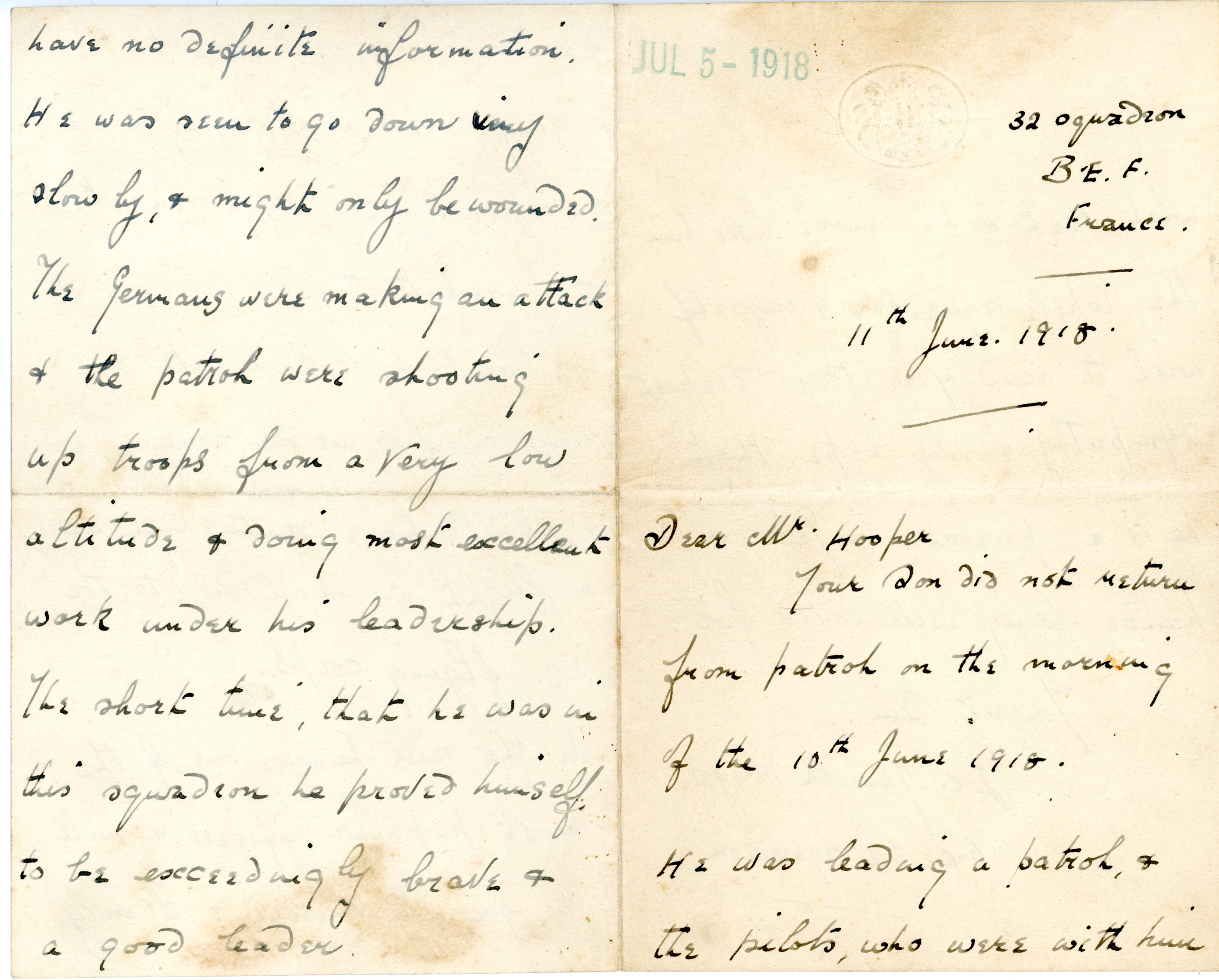

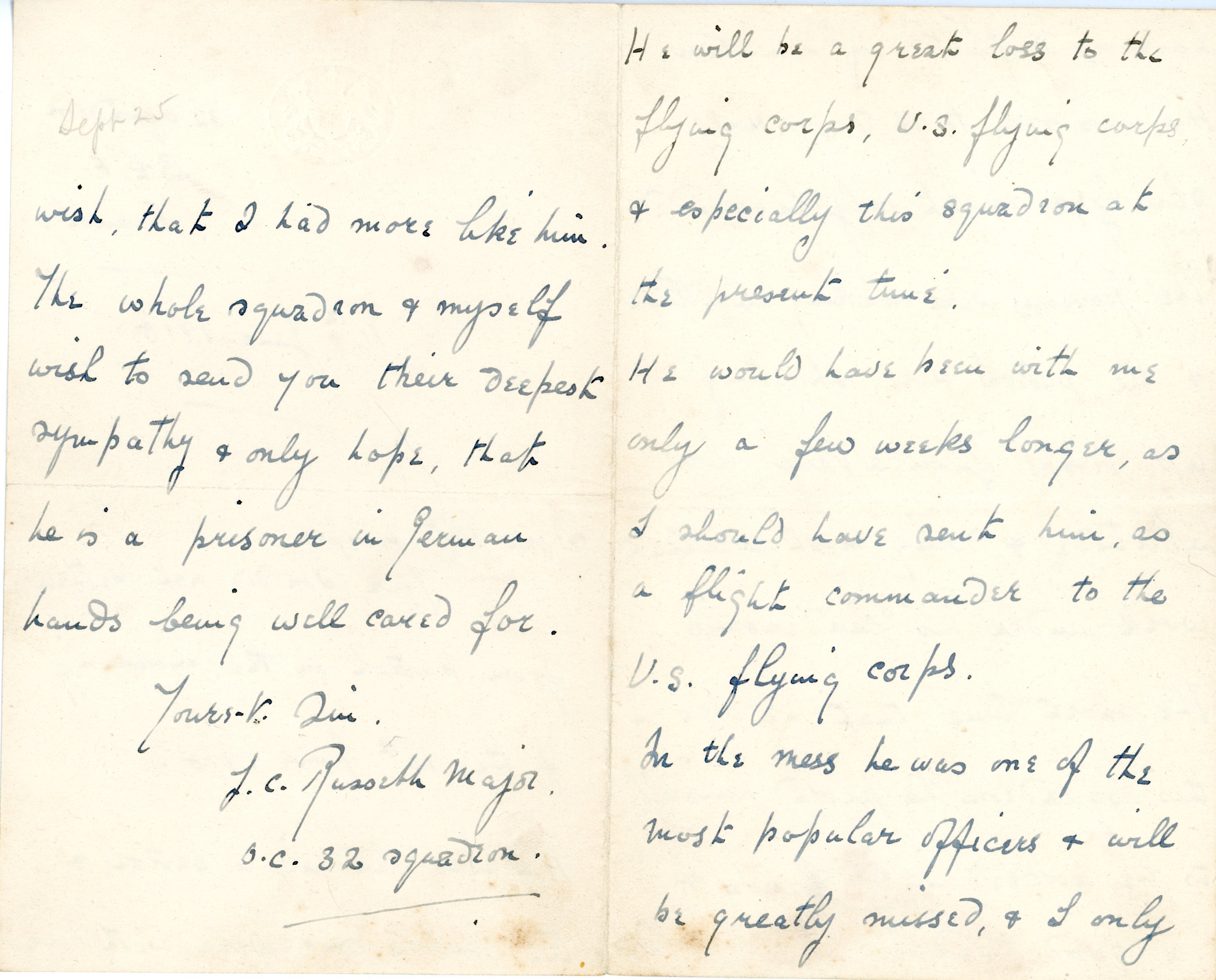

The next day, June 11, 1918, Major Russell, the C.O. of No. 32 Squadron, wrote to Herbert Hooper, Parr Hooper’s father: “Your son did not return from patrol on the morning of the 10th of June 1918. He was leading a patrol and the pilots who were with him have no definite information. He was seen to go down very slowly and might only be wounded.”

This letter, along with Hooper’s letter of June 9, 1918 and his short note from that evening, reached his parents on July 5, 1918. The Hoopers had three days previously, received a telegram from the War Department informing them that Parr Hooper was “officially reported missing in action.” Meanwhile, a letter Muriel Whiting wrote to Hooper on June 5, 1918, had been returned to her on about June 24, 1918, with the annotation “missing in action.” Both Herbert Hooper and Muriel Whiting sought further information. In response to her inquiry, Muriel Whiting, in August 1918, received a forwarded account from Bateman, which reads in part: “Lieut. Hooper was brought down in a steep spiral, and he crashed into the enemy’s lines. . . . It is impossible to say if he was himself hit, but it is probable that he was killed in the fall.” Having also received Bateman’s address, Muriel Whiting wrote to him directly; his reply was slightly less pessimistic: “I do not know what happened but one second I saw him drop his bombs & next time I saw him (about 15 seconds after I suppose) he was going down in a spiral. I then saw him hit the ground & a cloud of steam came from the machine. (Most probably the radiator burst on hitting the ground & the water on engine caused the steam.) They say he dropped his bombs just before going to attack a hun two-seater machine. . . . As the Anti Air-craft shells were pretty bad I thought he or the machine was hit by one of them, but of course he or the machine might have been hit by the two seater….”150

This letter, along with Hooper’s letter of June 9, 1918 and his short note from that evening, reached his parents on July 5, 1918. The Hoopers had three days previously, received a telegram from the War Department informing them that Parr Hooper was “officially reported missing in action.” Meanwhile, a letter Muriel Whiting wrote to Hooper on June 5, 1918, had been returned to her on about June 24, 1918, with the annotation “missing in action.” Both Herbert Hooper and Muriel Whiting sought further information. In response to her inquiry, Muriel Whiting, in August 1918, received a forwarded account from Bateman, which reads in part: “Lieut. Hooper was brought down in a steep spiral, and he crashed into the enemy’s lines. . . . It is impossible to say if he was himself hit, but it is probable that he was killed in the fall.” Having also received Bateman’s address, Muriel Whiting wrote to him directly; his reply was slightly less pessimistic: “I do not know what happened but one second I saw him drop his bombs & next time I saw him (about 15 seconds after I suppose) he was going down in a spiral. I then saw him hit the ground & a cloud of steam came from the machine. (Most probably the radiator burst on hitting the ground & the water on engine caused the steam.) They say he dropped his bombs just before going to attack a hun two-seater machine. . . . As the Anti Air-craft shells were pretty bad I thought he or the machine was hit by one of them, but of course he or the machine might have been hit by the two seater….”150

When, after some days, no word of Hooper reached No. 32 Squadron, it presumably fell to his roommate, Caswell, to go through his possessions. Hooper’s flying gloves, his shaving mirror, uniform insignia and extra buttons, his log book and R.F.C. transfer card, and a booklet of photo negatives were eventually received by his family. It is conceivable that, given the opportunity, Caswell would have done for his roommate what Rogers had done for his (Glentworth) and tried to locate Hooper’s crash site once the area was no longer in German hands. But Caswell, admitted to hospital in the latter part of June 1918 and then transferred to No. 60 Squadron, became a P.O.W. in mid-September, and was in no position to scour the countryside near the Château de Sorel. 151

Hooper’s father’s inquiries elicited no information either as to Hooper’s fate or a grave site. In June 1919, “in view of the time which has elapsed,” the War Department officially changed Hooper’s status from “missing in action” to “killed in action.” Herbert Hooper redirected most of his efforts from the search to winding up his son’s estate and ensuring that he was suitably memorialized. He supplied information for obituaries in the 1919 volume of the Transactions of the Society of Naval Architects and Marine Engineers and in Cornell University publications. It was presumably also he who arranged for Hooper’s letters home to be typed, duplicated, and bound—it was in this form that I first became aware of the letters. Herbert Hooper died in early 1924; Margaret Hooper lived until 1927. Not long before she died, Elliott White Springs sent her copy number 33 of the special edition of War Birds that he had had printed for members, or survivors of members, of the two Oxford detachments.

In 1937, the Aisne-Marne American Cemetery and Memorial near Belleau Wood in France was dedicated; Hooper’s name appears there on the Tablets of the Missing. He is one of thirty U.S. airmen who died in air fighting or accidents in France or Belgium whose graves are unknown, and one of five such men from the second Oxford detachment—the others being Galloway Grinnell Cheston, Linn Humphrey Forster, John MacGavock Grider, and Reuben Lee Paskill. 152

Postscript

In late 1919, Frederick William Zinn, an aviator who had been charged with locating graves of American pilots, wrote to Herbert Hooper that “German records show that on the date [Hooper] was missing, they shot down an S.E. 5a type of machine . . . at Ressons-Sur-Matz, occupant unidentified.”153 In the list of “Abschüsse feindlicher Flugzeuge und Ballone im Juni 1918” [“enemy planes and balloons shot down in June 1918″] published in the August 8, 1918, issue of the Nachrichtenblatt der Luftstreitkräfte, an entry for June 10, 1918, credits Willy Laabs with an S.E.5, the only machine of that type in the list for that date. At least since 1998, when Norman Franks, Frank Bailey, and Rick Duiven published The Jasta War Chronology: A Complete Listing of Claims and Losses, August 1916-November 1918, Laabs, a pilot with Jagdstaffel 13 of Jagdgeschwader II, has been linked to the shooting down of Hooper’s S.E.5a C9626.154 Given the fierce anti-aircraft artillery activity in the vicinity of the Château de Sorel and the reported presence there of at least one enemy two-seater, the Laabs claim—like many on both sides—should be regarded with some caution.155

mrsmcq September 13, 2019

Notes

(For complete bibliographic entries, please consult the list of works and web pages cited.)

1 Hooper’s place and date of birth are taken from Ancestry.com, U.S., World War I Draft Registration Cards, 1917-1918, record for Parr Hooper. The entry for Hooper in Maryland War Records Commission, Maryland in the World War, 1917–1919, gives his birthplace as Pikesville. It is likely he was born at the Parr country residence, Fernwood, in Green Spring Valley in Baltimore County, not far from Pikesville. Hooper’s date and place of death are taken from the page for June 10, 1918, (stamped “211”) in the RFC/RAF No. 32 Squadron Record Book. The photo is one Hooper had taken at the Studio Cecil in Ayr in the spring of 1918.

2 Information on Hooper’s descent is based on personal and family knowledge and documents available at Ancestry.com. On the Parrs, see Barnard, Early Maltby. On Parr Hooper and his family, see also the Introduction to Hooper, Somewhere in France.

3 Baltimore Polytechnic Institute, Annual Register Twenty-Fifth Academic Year 1909–1910, p. 70.

4 Jackman, ed., The Cornell 1913 Class Book, p. 147.

5 See Cornell University, Catalogue Number 1913–1914, p. 154 (842); and “Alumni News,” p. 354. A letter (unpublished, in my possession) from Hooper to his mother, postmarked December 5, 1915, shows that at this date he was working for N. Y. Ship

5a Letter from Hooper to his mother (unpublished, in my possession) dated August 17, 1917. Ironically, it would be two men from this class who did not sign up to go to Italy who ended up there: Dewitt Coleman and Thomas Franklin Fielder. Four others from this class went to France: James Frisbee Crankshaw, Harry Daniel Hundley, Arthur Sanford Richards, and Murray Kenneth Guthrie. All six men sailed on September 25, 1917, for England on the Saxonia. See Duncan, “The Real Italian Detachment,” regarding the men in this group.

6 “Ground School Graduations [for August 25, 1917]”; letter from Hooper to his father (unpublished, in my possession) dated August 18, 1917.

7 Information in this paragraph is based on Hooper’s letters to his parents from August and September 1917 (unpublished, in my possession).

8 Hooper, Somewhere in France, letter of September 21, 1917, subsequent entry dated September 30, 1917.

9 Hooper, Somewhere in France, letter of September 21, 1917, subsequent entry dated September 26, 1917.

10 Hooper, Somewhere in France, letter of September 21, 1917, subsequent entry dated September 24, 1917.

11 See David K. Vaughan’s Appendix B (“Springs’s Use of the Grider Diaries in War Birds”) in Springs’s Letters from a War Bird regarding the authorship of this passage in the diary entry for October 3, 1917.

12 Hooper, Somewhere in France, postcard dated October 3, 1917, and telegram stamped received October 7, 1917.

13 Hooper, Somewhere in France, letter of January 8, 1918.

14 Hooper, Somewhere in France, letter of October 7, 1917.

15 Ibid.

16 Quotation from Hooper, Somewhere in France, letter of October 18, 1917.

17 Quotation from Hooper, Somewhere in France, letter of October 27, 1918. Other information in this paragraph is based on Hooper, Somewhere in France, Chapter 2, passim.

18 For information on the machine gun school site, see, i.a., Wessex Archaeology, Belton House, which was created for VideoText Communications Ltd’s “The Forgotten Gunners of WWI.”

19 Hooper, Somewhere in France, letter of November 4, 1917.

20 Foss, diary entry for November 3, 1917.

21 Hooper, Somewhere in France, letter of November 4, 1917.

22 Ibid.

23 Ibid.

24 Ibid.