(Dora, Alabama, May 19, 1895–Kingfield, Maine, October 7, 1985)1

Oxford & Grantham ✯ Training with No. 50 Squadron ✯ Stamford, Thetford, Turnberry ✯ France

Palmer’s father’s family can be traced back to one of the English Palmers who came to Virginia in the first part of the seventeenth century. Descendants moved to South Carolina and Georgia, and in Palmer’s grandfather’s generation, to Alabama. Palmer’s father, Robert Henry Palmer, broke with the family tradition of farming and went into commerce, becoming a leading businessman in Walker County, Alabama.2 His first wife died in 1885; Robert Thomas Palmer was the first child of his second marriage, to Joanna Gertrude Jackson, whose ancestors had similarly moved from Virginia to Georgia and then Alabama. Sometime prior to 1910, the Palmer family relocated from the small town of Dora (originally called Horse Creek), where Robert Thomas Palmer was born, to nearby Jasper.3

Palmer attended college at the University of Alabama in Tuscaloosa, graduating with a degree in electrical engineering in 1916.4 When he registered for the draft in June 1917, he was in Toledo, Ohio, working as an electrical engineer for the Toledo Railway and Light Company, but he soon applied to the Aviation Section of the Signal Corps.5 He went to Chicago for his physical exam and for tests designed to weed out those unsuited to flying: vision and hearing tests, and extensive tests for balance. He was whirled about in a chair “and if it had not been especially constructed I would have been thrown out about 10 feet. Then stopping the chair suddenly they told me to sit straight up. I couldn’t do it. . . . This was exactly right and I passed. . . . Some of the men after the chair test were so sick and nauseated that they were disqualified and some of them it did not affect enough so they were disqualified.”6

By early July 1917 Palmer was enrolled in ground school at the School of Military Aeronautics at Ohio State University at Columbus.7 Soon after he arrived he wrote his parents that “I can receive the wireless calls just twice as fast as the rest of the fellows in my quarters. I can receive clearly 8 words a minute to their 4.”8 This is worth noting, as mastering Morse code was a stumbling block for many of the students—ironically, as few of the men who became pilots ended up needing it.9 Palmer continues: “My lack of military training and experience is holding me back in the drilling as most of the fellows here have had several years of military work.” Some of the students had been in a college cadet corps or R.O.T.C., but Palmer, coming from regular college course work, was probably not actually in the minority. “We are cadets just the same as the ones at West Point and Annapolis except that we have more privileges and our course is much shorter. After a month or six weeks here we go to Dayton, Ohio, to the advanced training camp.” This was among the first of many assumptions about the future that would prove wrong; the war effort involved a great deal of extemporization and frequent changes of plan.

When Palmer’s ground school class of about thirty men graduated September 1, 1917, he was among the twenty-four who had been selected to do their advanced training in Italy. They travelled to Mineola on Long Island and became part of a detachment of 150 men—they called themselves “the Italian detachment”—setting out for Europe. Palmer wrote his parents in the first part of October that “We sailed from New York Sept. 18 at noon on the * * * * one of the Canord [sic; sc. Cunard] liners and one of the largest and fastest boats on the world”; the censor has removed the name of the ship, Carmania. “We went through * * * * [Halifax] and stayed there two days and then came on to * * * * [Liverpool] with a convoy of other boats. . . . I didn’t see any submarines but we were close to them. A tramp steamer was torpedoed 10 mile in front of us and an American destroyer sank a submarine which attacked our convoy though I didn’t see the fight as the tail end of the convoy was attacked and we were in front. This has been published in a London paper”—which presumably meant Palmer was not worried that his account would be censored. “It took us two weeks to cross the Atlantic as we were zig-zagging across to fool the Germans. We wore our life belts constantly most of the latter part of the voyage and kept submarine watch. I was on watch one night and was kind of disappointed in not seeing one.”10

Oxford & Grantham

When the Carmania docked at Liverpool on October 2, 1917, the detachment members learned that they were not to continue to Italy, but to go to Oxford University for training at the Royal Flying Corps’s No. 2 School of Military Aeronautics there—although apparently there was still some idea that Italy was possible. In his October letter Palmer writes “We will probably be here three weeks and then may go to Italy. I can’t tell what the government may decide to do. We had an Italian lesson every day on the boat which shows how sure of our plans we were.” One of their teachers had been Fiorello La Guardia, who may also have been responsible for the men having enjoyed the comfort of the Carmania’s first class state rooms.11

Once arrived at Oxford the 150 men of what came to be called the “second Oxford detachment” were split into two groups, and Palmer was in the larger group of ninety men who were housed in Christ Church College with detachment member Elliott White Springs in charge. Palmer’s roommates were his ground school classmate Thomas John Herbert and a man from the class ahead of him, Parr Hooper.12 Palmer noted that “It is very damp here but we keep a fire going in our room all of the time so that I am not affected by it much.”13 In the aftermath of bibulous celebrations that also included members of the first Oxford detachment (who had arrived at the beginning of September), all 150 men were moved to Exeter College, so that all the Americans were housed together. Hooper wrote from Exeter that he had “the same two roommates here that I had at Christ Church and we get along very well. We drew a convenient room on the second floor. There is no heat and we wash in cold water in basins in a little yard outside the court.”14

As classes at Oxford covered much of the same material that the men had had at ground school in the states, the cadets were not overburdened with homework or studying but were free to explore Oxford and the surrounding countryside. Palmer wrote that he had “taken several long walks and canoe rides in the country and on the river here.” He was ambivalent about England. It was

very pretty and everything is very green. The whole country looks like some rich man’s private park as it is so well tended. I suppose the greeness [sic] and abundance of grass must be due to the fact that it rains every night. The English might call it fog but it is like rain to me. There is an abundance of fruit here but it is not sweet and has no distinctive taste. . . . It is an impossibility to see anything here but the surrounding country here as every house and yard or garden as they call it has a 20 foot wall built around them to keep out prying eyes. The whole town is a collection of high walls. . . . England is very pretty but I would not like to live here under any circumstances. I am too scientific. I suppose I’d tear down the old traditions and build some new sanitary buildings. It would be a sacrilege here to drive a nail in the floor. The telephone and trains are what ours were 30 years ago.15

Palmer, like many of his fellow cadets, noted that “Oxford is full of wounded and convalescent soldiers” and also that “The Americans are very popular and we have gotten a great deal of applause.”16

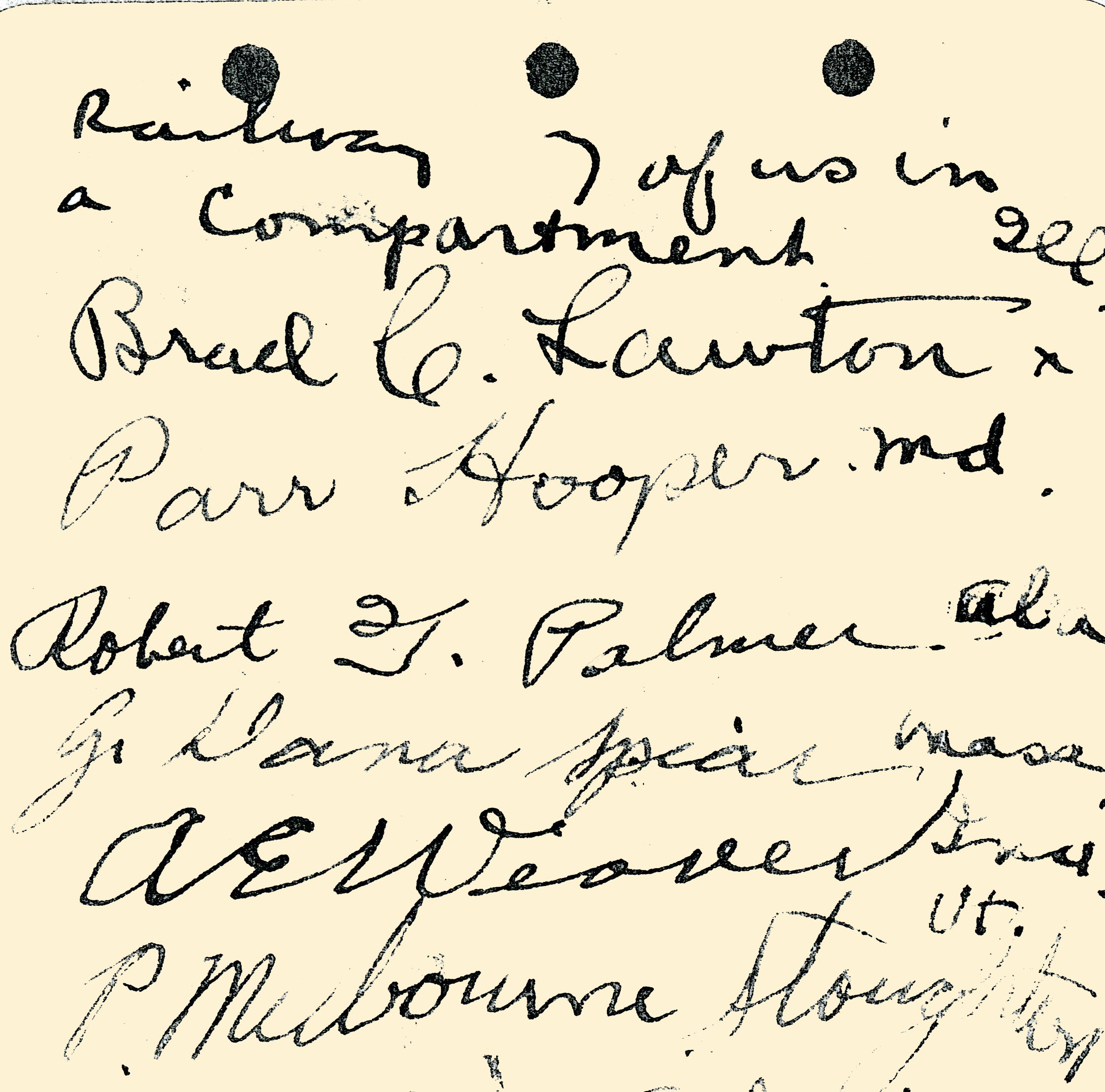

About a month after their arrival in England, the men learned that their time at Oxford was up. Twenty were selected to go to Stamford to start flying, but Palmer was among the 129 who were ordered to attend machine gun school at Harrowby Camp near Grantham in Lincolnshire (according to the War Birds entry for November 6, 1917, one member of the detachment, James Whitworth Stokes, stayed behind in Oxford to be operated on for appendicitis). On November 3, 1917, the men rose early to pack for the train journey north. The trip took about six hours, including an hour stop for lunch near Bletchley Park. A little further on, at Sandy, they changed cars, and Palmer completed the third class journey in a compartment with six others, including Hooper and also Fremont Cutler Foss, who got his compartment mates to autograph his diary page for that day.

The huts at Grantham were a step up from the rooms at Exeter College. Hooper wrote his parents that “The living conditions are very good. We have hot and cold showers.” He also noted that “It looks like we got sent here because there was no other place to send us to—playing for time.”17

The day after their arrival at Grantham was Sunday and the cadets were at leisure. Hooper and Palmer explored the area. In the morning they “took a walk up over and around a neighboring hill. We got a good view of the town and found a flying school by walking towards the place where the machines were landing. It is an advanced school. We saw some interesting machines and some good flying.” They wore themselves out with another long walk in the evening.18

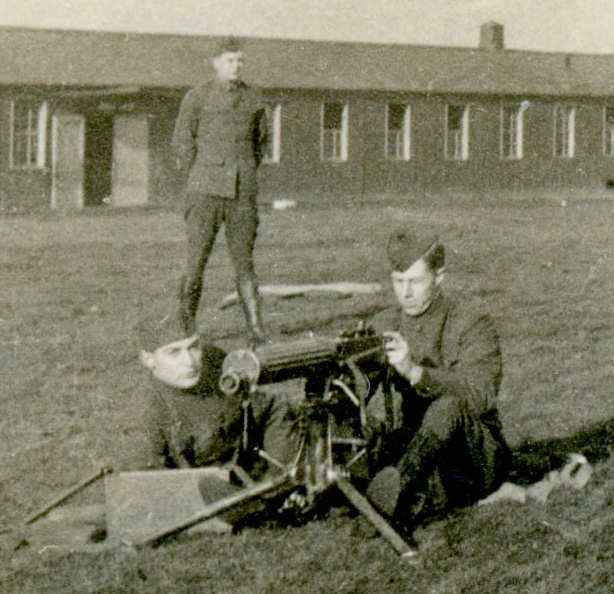

The next day instruction began on the Vickers machine gun. Hooper took a photo of Palmer working the gun, and Palmer also appears in a photo taken by Joseph Kirkbride Milnor of cadets and an officer gathered around a Vickers. Hooper and Palmer continued to pal around together during free time on weekends. On November 11, 1917, they “took a bike ride across country to an advanced flying school where we saw some 130 mile an hour scout machines.”19 There were R.F.C. airfields at Spitalgate and at Harlaxton, both within biking distance of Harrowby Camp; Spad 7s and S.E.5s—fast scout machines—were flown at Harlaxton.20

A few days later it was learned that fifty of the cadets at Grantham would be able to leave shortly for training squadrons; when the fifty names were announced, Hooper’s was among them, but Palmer’s not. On Hooper’s last weekend (November 17 and 18, 1917) at Grantham, he and Palmer continued their explorations. “Saturday afternoon Robert Palmer and I took a long walk. It was a bit foggy (as usual) but we ran across some very pretty places and resolved to go out again on Sunday. . . . Sunday was a beautiful day. Bob and I started out right after breakfast with our cameras and made our first assault on the cathedral spire.”21 They had gone from Belton Park, north of Grantham, where Harrowby Camp was located, into Grantham itself; the “cathedral” was actually St. Wulfram’s parish church in Grantham, remarkable for the height of its spire. “Then we hired bicycles and went south along a high road parallel to the valley. The country was especially beautiful, and the air was swarmed with aeroplanes. We went up a pretty byroad and entered an estate at Stokes”—this was Stoke Rochford Hall, at the time owned by Christopher Hatton Turnor. “I broke a chain on the way home, Robert towed me to a town where we had it fixed while we ate dinner at the home of a villager. (War talk–he was in the Imp. Army.) The chain broke again and I towed Robert in.”22

Having completed the course on the Vickers gun, Palmer and the other cadets still at Grantham now studied and practiced on the Lewis gun. Palmer evidently applied himself: he had received a mark of “good” on the Vickers, but pulled ahead to a “very good” at the end of the two-week Lewis gun course on November 30, 1917.23

Training with No. 50 Squadron

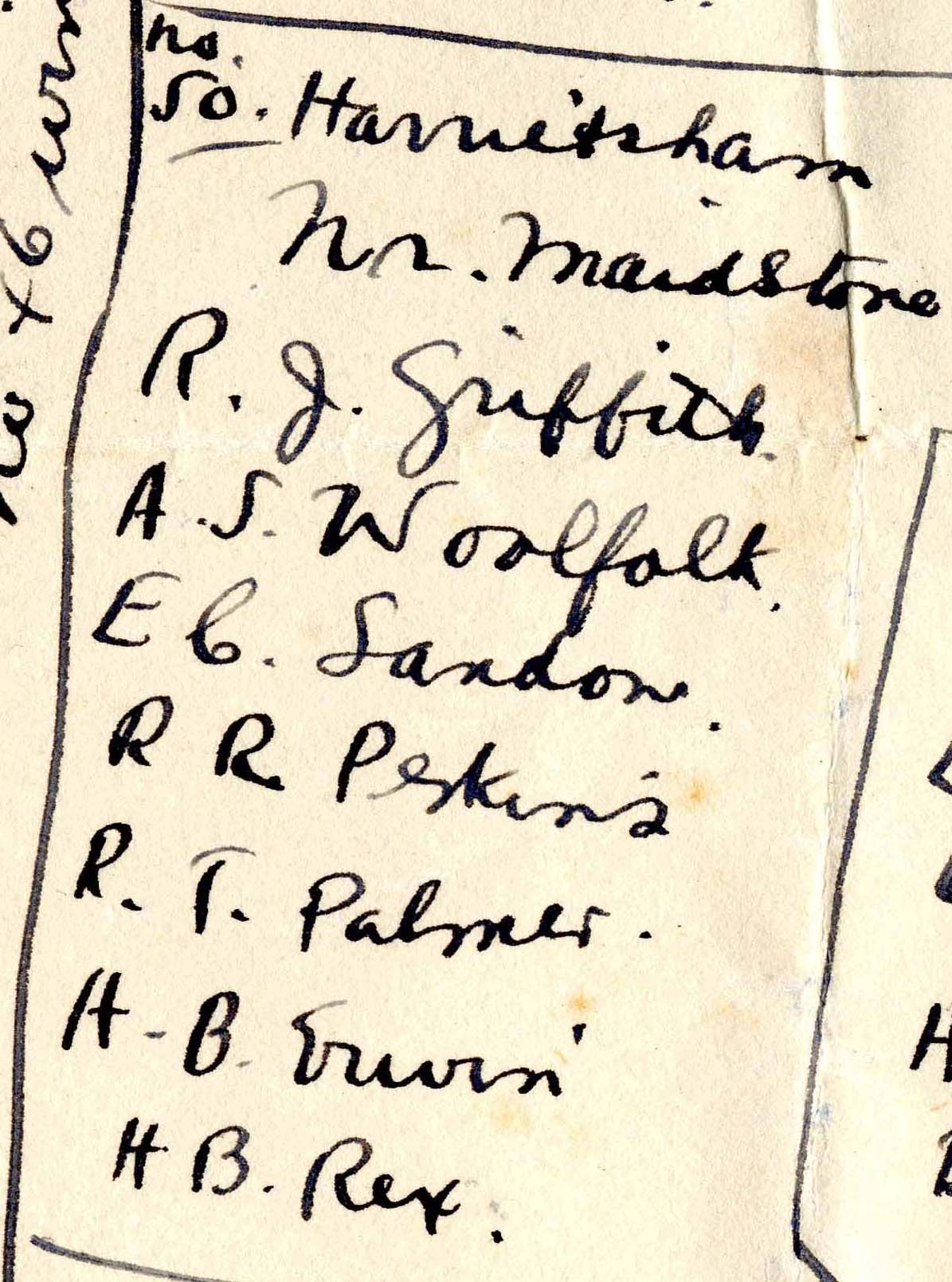

On December 3, 1917, the men still at Grantham were posted to squadrons. Palmer, along with Edward Carter Landon, Robert Jenkins Griffith, Harrison Barbour Irwin, Pryor Richardson Perkins, Hilary Baker Rex, and Albert Sidney Woolfolk (all of whom, with the exception of Rex, had been in Palmer’s O.S.U. ground school class), was assigned to No. 50 Squadron in Kent; No. 50 was a home defense rather than a training squadron.24 Its aircraft at the turn of the year included the B.E.2e and the A.W. FK.8, both two-seaters used for reconnaissance and bombing, and the B.E.12b, a single-seater night fighter.25

The squadron’s headquarters was at Harrietsham, near Maidstone, but its flights were at this time detached to Bekesbourne and Detling.26 Griffith, Irwin, and Woolfolk went to C flight at Bekesbourne near Canterbury, while Palmer, along with Landon, Perkins, and Rex, was assigned to B flight at Detling.27 In a letter dated December 12, 1918, Palmer wrote that: “Our aerodrome is quite isolated and there are lots of small woods and large fields with real hills to walk over so that I should be quite contented here. We have a good fire and library in our mess room and I never imagined that one could ever be so free while in the army. . . . There are several dogs here belonging to the English officers and I can generally get one of them to go with me when I walk.”

Palmer soon got his first opportunity to fly. A few days after his arrival, he wrote home that “I enjoy flying very much and have not had the slightest nervousness or fear while in the air which is surprising as most people are a little nervous on their first flight.”28 But it was snowing as he wrote, and he goes on to say that “I haven’t flown alone yet and in fact haven’t done much flying of any sort on account of the weather so that if I stay here it will be quite a long time before I am a finished aviator.” Like all R.F.C. pilots, Palmer kept a flying log book, but either he did not record his initial flights (perhaps because they were not instructional) or those pages are missing. There is, however, a summary, which indicates that while at No. 50 he got in three hours in a B.E.2e and an hour in an A.W.29

Palmer also mentions that he “was at a certain English town last week during an air raid by Germans”—this would have been the early morning raid of December 6, 1917 (also mentioned by his fellow Oxford detachment members Walter Ferguson Halley and Uel Thomas McCurry). “I could hear the aeroplanes but could not see them. It looked quite lively with search lights playing through the air with anti-aircraft shells bursting everywhere in the air. British machines took the air after them and it was a thrilling sight to see them leave the ground with their flaming engine exhausts.” (Rex noted in his diary that four planes from their flight went up.30) R.F.C. planes were not able to intercept the raiders, but two of the Gotha bombers succumbed to anti-aircraft fire; one came down at Rochford in Essex, the other near Canterbury.31 Palmer wrote that he “saw one of them and inspected the construction very carefully. It was a very large one with 2 engines and 3 passengers.”32 The Gotha that came down in Kent was burned by its crew before their capture, so that, if this is the one Palmer saw, as seems likely, it would have been a smouldering wreck.33

Stamford, Thetford, Turnberry

Towards the end of January 1918, after nearly two months at No. 50 Squadron and not much flying, Palmer, along with Landon, Perkins, and Rex, was posted to No. 5 Training Depot Station at Easton on the Hill about two miles south-southwest of Stamford (the second Oxford detachment members sent to Stamford in early November had been assigned to No. 1 T.D.S. about three miles to the east, near Wittering).34

Palmer’s log book shows that on February 6, 1918, he flew twice as a passenger, in a B.E.2e early in the morning, and in an R.E.8 in the afternoon.35 His next recorded flight, again in a B.E.2e, was not until March 4, 1918. Bad weather cannot account for Palmer’s not flying during February, as the log books of second Oxford detachment members Pryor Richardson Perkins and John Warren Leach, also at No. 5 T.D.S. at this time, show them flying during this period. However, Perkins and Leach had been assigned to 2 flight, while Palmer was in 4 flight. Leslie A. A. Benson was also in 4 flight at 5 T.D.S. during this period, and his log book is similarly blank in February 1918; it seems likely that 4 flight, in contrast to 2, had insufficient planes and/or instructors.

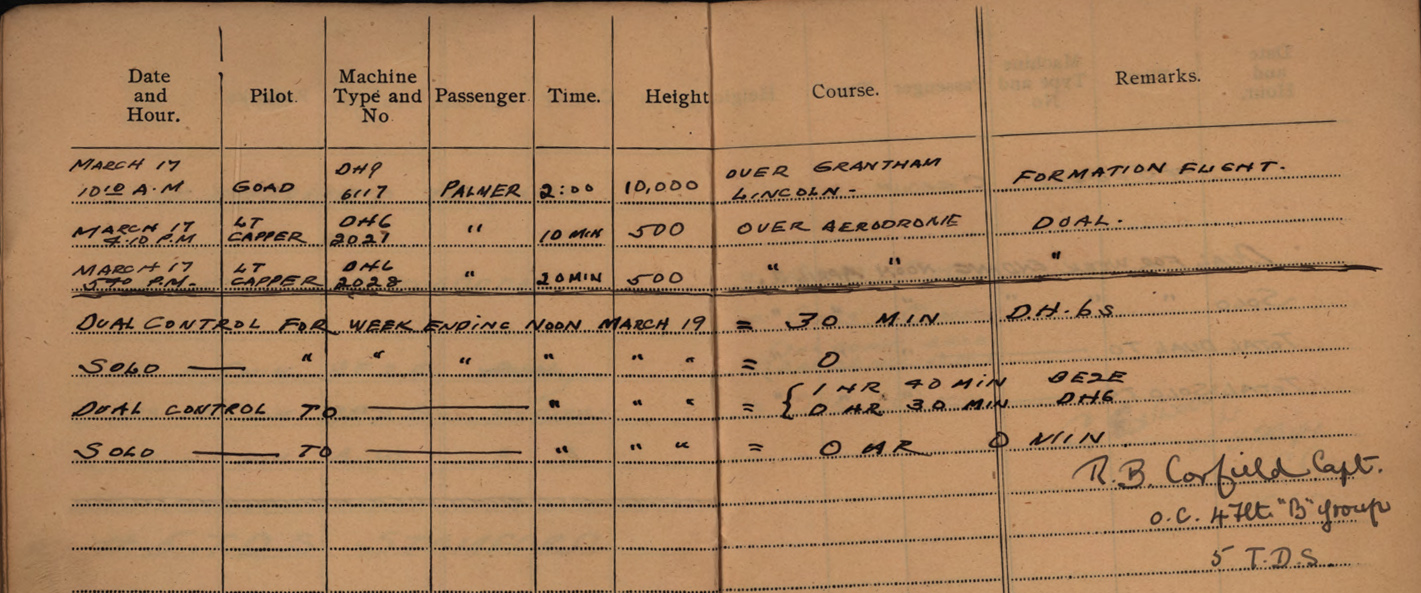

Palmer made three more short flights as a passenger in a B.E.2e on March 6, 7, and 8, 1918, before moving on to flying in DH.6s, two-seater training planes, and logging two hours and twenty minutes in DH.6s over the course of the month. On March 17, 1918, in a flight that did not count against his time towards graduation, he was a passenger in a DH.9 flown by his fellow second Oxford detachment member John Marion Goad: they flew for two hours, part of the time at 10,000 feet, from Stamford to Grantham and back.

Goad had by this time already done enough flying to qualify for a commission, and Pershing’s recommendation that he be commissioned a first lieutenant had been sent to Washington on February 26, 1918. Palmer, meanwhile, was among the many pilots in training who, for a variety of reasons, were still awaiting commissions. In a cable to Washington dated March 13, 1918, Pershing describes the situation of the approximately 1400 aviation cadets in Europe, some of whom had waited three months to start flying training, and some of whom, after five months, were still waiting and might have to wait another four. “All of those cadets would have been commissioned prior to this date if training facilities could have been provided. These conditions have produced profound discouragement among cadets.” To remedy this injustice, and to put the European cadets on an equal footing with their counterparts in the U.S., Pershing asked permission “to immediately issue to all cadets now in Europe temporary or Reserve commissions in Aviation Section Signal Corps. . . .”36 Washington approved the plan in a cable dated March 21, 1918, but stipulated that the commissioned men be “put on non-flying status. Upon satisfactory completion of flying training they can be transferred as flying officers.”37 Thus Palmer was among the men recommended for commissions as “First Lieutenants Aviation Reserve non flying” in a cablegram from Pershing to Washington dated April 8, 1918.38

In the first weeks of April Palmer again for some reason logged no time in the air, only resuming flying on April 20, 1918, again in a DH.6.; on that day he practiced landings for the first time: “over aerodrome 3 landings. Good.”

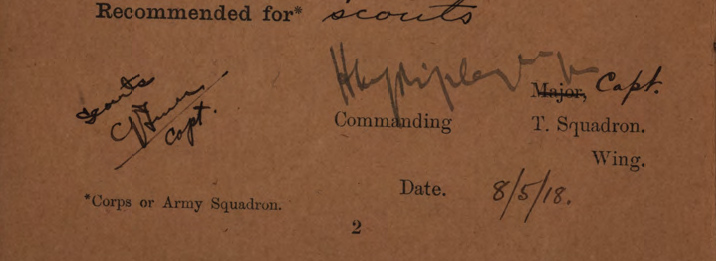

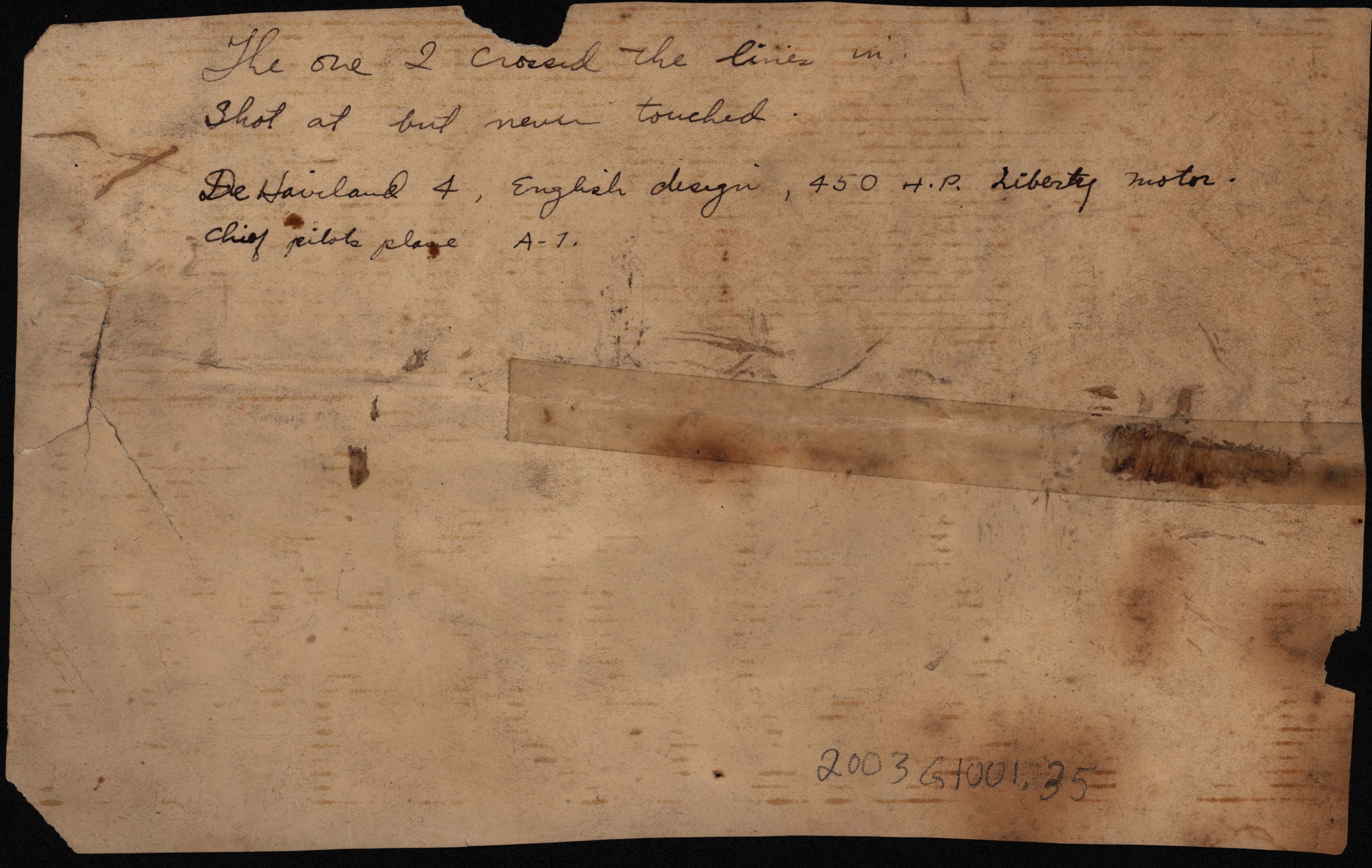

Finally in May things started to pick up. After many practice landings, Palmer was cleared to fly solo, which he did in a DH.6 on May 6, 1918. Two days later he made a cross-country flight—a prerequisite for graduation from this stage of R.A.F. training—to Spittlegate (Spitalgate), near Grantham, and on May 14, 1918, he passed his height test, flying a B.E.2e at 9200 feet. Finally, on May 18, 1918, he flew his first solo in an R.E.8, a two-seater reconnaissance and bomber aircraft; this was the final hurdle for graduation. By this time it must have been clear that Palmer would go on to be a reconnaissance or bomber pilot, despite his having been recommended earlier by the officer commanding No. 5 T.D.S., Hugh William Grey Ripley, for scouts, i.e., for single-seater fighter planes.39

Palmer experienced his first crash, fortunately minor, on May 21, 1918, when his rudder jammed while he was taking off. Nevertheless he went on that day to practice “diving on targets” and “steep turns and spirals.” The next day he did photography practice, exposing sixteen plates. By the end of the month, he was able to record forty-three hours of flying time, including over thirty-one of solo flying; the flightless days in February and April no longer mattered. He was placed on active duty on May 28, 1918.40 The preceding day he, along with second Oxford detachment members Clayton Knight, William Henley Mooney, and Clarence Bernard Maloney, were posted from Stamford to Thetford where No. 12 Training Squadron, No. 35 T.D.S., and No. 128 Squadron were located. Palmer was initially assigned to No. 128, which had been formed earlier in the year as a day bombardment squadron.41 At this stage, No. 128 was evidently focused on training (and it did not become operational, but rather was disbanded in July 1918).

Palmer made his first flight at Thetford as a passenger in a DH.6 on June 4, 1918, and was back to flying a DH.6 solo two days later. He then went from passenger to pilot on an R.E.8 before going up as a passenger in a DH.9 on June 10, 1918. His log book indicates that the next day he began training at No. 12 T.S., flying solo in DH.6s and R.E.8s, and once as a passenger in a DH.9. Finally, in “stormy weather” the afternoon of June 18, 1918, when his was the “only machine up,” Palmer flew DH.9 [D]5593 for forty-five minutes (like many pilots, Palmer omitted the letter prefix when recording aircraft serial numbers in his log book). Perhaps because of continued poor weather, he did not go up again until June 24, 1918, but from then until June 28, 1918, he went up solo in DH6s and DH9s at least once, and sometimes three times, each day, practicing aerial fighting and machine gun firing. By the end of June he had flown just over seventy-five hours, almost sixty of them solo.

Palmer’s log book entries for July and the first part of August 1918 are extremely sketchy: he notes being transferred to Turnberry School of Aerial Fighting, but does not note dates or flights; his R.F.C. Training Transfer Card indicates he was assigned to Turnberry on July 4, 1918, and then to A.E.F. France on July 13, 1918.

France

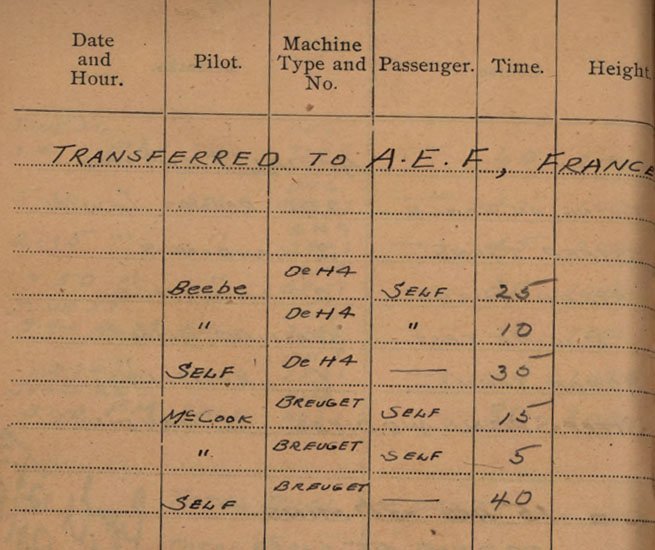

Palmer’s next log book entry is undated, but it indicates that he was a passenger in a DH-4 piloted by “Beebe.” This would have been David Chapin Beebe, who, from about July 16 until about August 10, 1918, was at the Second Aviation Instruction Center at Tours.42 After two short flights as Beebe’s passenger, Palmer made a thirty-five minute flight as the pilot of a DH-4—this was the American-built version of the British DH.4, and not very different from the DH.9s Palmer had trained on. The DH-4 entries are followed by ones showing that second Oxford detachment member Forrest Thomas McCook took Palmer up twice in a Breguet, and that Palmer then took the plane up solo. On August 7, 1918, Beebe and McCook were among those ordered to the American 1st Air Depot at Colombey-les-Belles, from which they were assigned to the U.S. 50th Aero Squadron.

Palmer, however, remained at Tours. His flying, particularly his excellent landings, had attracted attention, prompting the higher-ups to select him as an instructor.42a From August 12 through August 21, 1918, according to his log book, he took on the task of “Instructing pupils DeH.4s Liberty Motors 400 H.P. (at times).” (His fellow second Oxford detachment member William Hamlin Neely was also serving as a DH-4 instructor at Tours at this time). Some of Palmer’s student passengers can be tentatively identified from his log book entries: Frederick Russell Zinn, William Landon Bradfield, Thayer Denton Hall, and Edward Moses Morris.

Palmer also did some ferrying. On August 15, 1918, taking a break from DH-4s, he piloted a Sopwith 1½ Strutter to Issoudun. He ferried a DH-4 back to Tours the next day, and the following day made the considerably longer flight in a DH-4 to Colombey-les-Belles, thus getting close to the front for the first time. On August 21, 1918, he made two flights, the last ones recorded in his log book. During the first he was “chateau hopping”; he then flew to Vendome and back. At the end of this log book page, Palmer wrote “regulation U.S. Pilot Book from now on.”43 Unfortunately that book appears not to be extant. But, although Palmer ceased using the R.F.C. issued book to record individual flights, he did use it to write summaries of his activities.

Thus, according to his log book, Palmer, from August 25 through October 15, 1918, was stationed at Chaumont, and from October 16 through February 5, 1918, at Toul. These dates turn out not to be accurate; they are perhaps approximations produced from memory.

In a letter home dated September 30, 1918, Palmer described a recent trip he had made ferrying a plane to the front.44 Poor weather and low clouds meant he flew most of the time at “1000 to 1500 feet”—making map navigation difficult—“and as the ground became higher near the front I flew the remainder of the distance at about 300 feet. I had a nice trip though.” He did not linger once the plane was delivered: “I had to hurry to get a truck in order to catch a good train back to Paris,” where he wrote his letter. He is careful not to mention place names, but notes that the distance from his starting point to the squadron where he delivered the plane was over two hundred miles. This suggests that his starting point was considerably farther from the front than was Chaumont. If he was still stationed at Tours in the latter part of September, the distance would fit.

According to John Sloan’s Wings of Honor, Palmer was assigned to the 85th Aero, an observation squadron, on October 11, 1918.45 An entry in the diary of Eugene Hornby Blanche suggests that Palmer actually arrived at the 85th and Chaumont-Hill 402, the aerodrome southeast of Chaumont, on October 12, 1918: “Two D.H.4s were piloted into the field this morning by Lieuts. Palmer and Sisson, both new pilots assigned to the squadron”—Winfield Earl Sisson was a member of the first Oxford detachment.46 (Allison Henderson Chapin of the second Oxford detachment was also a member of the 85th Aero.)

About ten days later, Sisson asked Blanche “if I would ride with him and needless to say as I like his flying very much, I accepted. Palmer asked [Hubert Matthew] Rice if he wished to ride with him and Rice also accepted. They are both good pilots and easily the best I have ever ridden with.”47

Palmer, in his log book summary for his time at Chaumont, mentions “Dropping French war loan bombs”; this is clarified by Blanche’s entry for October 25, 1918, at Chaumont: “Sisson and I, Palmer and Rice, and [Harold] Cohen and [Theodore Rector] Brace scattered propaganda over the town all afternoon in an attempt to promote the French Liberty Loan Drive.” Blanche’s entry shows that Palmer was at this date still at Chaumont and not at Toul, as Palmer’s log book summary dates indicate.

On November 1, 1918, still at Chaumont, Blanche describes how “A couple of nights ago an officer attached to G.H.Q. [also at Chaumont] engaged us in conversation and wanted a ride in an airplane in the worst way. . . . Palmer consented to take him up and I loaned him my coat. Palmer gave as pretty an exhibition of stunt flying as one could wish for with a D.H.4 and as a result the little lieutenant got deathly sick with the result that my coat was a total wreck.”

Not until November 4, 1918, did the 85th, and Palmer, relocate to Gengoult Aerodrome at Toul. “We pulled into Toul late in the evening. . . . The officers obtained passes and we all rode in relays in the Dodge to the town of Toul where we had dinner at the Hotel Comedie.” Insufficient accommodations at Toul meant that the enlisted men, as well as some of the staff officers, were quartered in a château in Manonville, some ten miles north of Toul. On November 7, 1918, “an orderly motorcycle rider came in with orders from the Captain [Herbert Alfred Schaffner] for Palmer, Sisson, and I to report to him at Manonville and we went up after lunch. . . . We have planned an initial flight for tomorrow, using five ships.”48 In the event, only one plane, Sisson’s, was ready. Schaffner commandeered it and, with Blanche as his observer, flew to Metz and back without incident. Rain prevented flying on November 9, 1918, but on November 10, 1918, amidst rumors of an armistice,

We received orders to hold ourselves in readiness and an hour later received orders to proceed toward Conflans and pick up the movements of any troops northward along the road, also burning fires which might indicate the destruction of war material preparatory to a general withdrawal.

The flight was to be made in a V formation with the Captain and [Nathan Charles] Post leading. Palmer and Rice first on the right, and [David Bennett] Sain and [James Lafayette] Gober second on the right. Sisson and I were to be first on the left and Cohen and [James Christopher] Wallace [sic; sc. Wallis] second on the left.

We climbed to 13,000 feet over the field and headed north. Wallace and Cohen had to turn back on account of motor trouble and we flew in a diamond formation with Gober and Sain the rear point of the diamond.

We crossed the lines at about 14,000 feet and reached Conflans. We went through an aerial barrage and one or more of the flight were constantly hidden from view by the smoke of the exploding H.E.s [high explosives] . . . Out of the four ships that crossed the lines, two of them were shot up so badly that they were in the shop for repairs. Rice and Palmer were the luckiest without a single hole.49

The next day, according to Blanche, a photographic mission was scheduled, but the armistice intervened. Orders came that they “were to patrol along the front, remaining on our side of the lines”; it is probable, though not certain, that Palmer and Rice took part in these patrols from Pont-à-Mousson to Thiaucourt.

Afterwards “Palmer, Sisson, [Charles Reed] Gould [sic; sc. Goold] and I commandeered the Dodge and set out for Nancy about 5:00 in the afternoon. . . . It was as though a half a hundred New Year celebrations were rolled into one. . . .”50

Palmer’s summary of his time at Toul indicates that his duties, beyond observation flights, included: “testing instructing, ferrying carrying cognac [!], putting in flying time.” Although no longer recording individual flights in his R.F.C. log book, Palmer was keeping track of hours. He noted that while at Chaumont he logged 135 hours solo; at Toul, 120. He also, during some unspecified period, put in four hours at Paris (Orly) “flying Sissons DH.”

According to Palmer’s log book, he remained with the squadron at Toul until February 5, 1919. After that he had a long wait before he could return to the U.S. Finally, on June 17, 1919, at St. Nazaire, he boarded the U.S.S. Aeolus and sailed home, arriving at Hoboken on June 28, 1919.51 He became a patent attorney, initially in New York, and then in Boston.52

mrsmcq July 14, 2021; revised to reflect Blanche’s diary, July 26, 2021

Notes

(For complete bibliographic entries, please consult the list of works and web pages cited.)

1 Palmer’s place and date of birth are taken from Ancestry.com, U.S., World War I Draft Registration Cards, 1917–1918, record for Robert Thomas Palmer. His date of death is taken from Ancestry.com, U.S., Department of Veterans Affairs BIRLS Death File, 1850-2010, record for Robert T Palmer; his presumed place of death is taken from Ancestry.com, U.S., Social Security Death Index, 1935–Current, record for Robert Palmer. The photo is a detail from a group photo of his ground school class at O.S.U.

2 See “R. H. Palmer Passes Away.”

3 On Palmer’s family and descent, see documents available at Ancestry.com.

4 Corolla 1916, p. [101].

5 On his employment, see Palmer’s draft registration, cited above.

6 From a letter Palmer wrote to his parents on July 9, 1917, reproduced in “Robert Palmer, Jr., Writes Parents Interesting Letter.”

7 Ibid.

8 Ibid.

9 See Bingham, An Explorer in the Air Service, p. 52, regarding aspects of training that did not correspond to the practice of many pilots in France.

10 “A Walker County Boy in Royal Flying Corps.”

11 See La Guardia, The Making of an Insurgent, p. 167. But see also War Birds, entry for Sept. 20, 1917, where Major Leslie MacDill is given credit.

12 Hooper, Somewhere in France, letter of January 8, 1918.

13 “A Walker County Boy in Royal Flying Corps.”

14 Hooper, Somewhere in France, letter of October 27, 1917.

15 “A Walker County Boy in Royal Flying Corps.”

16 Ibid.

17 Hooper, Somewhere in France, letter of [November] 4, 1917.

18 Ibid.

19 Hooper, Somewhere in France, letter of November 13, 1917.

20 Sturtivant, Hamlin, and Halley, Royal Air Force Flying Training and Support Units, p. 302.

21 Hooper, Somewhere in France, letter of November 21, 1917.

22 Ibid.

23 Palmer, R.F.C. Training Transfer Card.

24 See Foss’s list of “Cadets of Italian Detachment Posted Dec 3rd” in Foss, Papers.

25 On the planes used at 50, see Philpott, The Birth of the Royal Air Force, p. 408.

26 “50 Squadron (home defense), location of B flight, December 1917-January 1918”

27 Rex, World War I Diary, entry for December 5, 1917.

28 Palmer, letter dated December 12, 1918.

29 Palmer, Pilot’s Flying Log Book.

30 Rex, World War I Diary, entry for December 6, 1917.

31 H. A. Jones, The War in the Air, vol. 5, p. 104.

32 Palmer, letter dated December 12, 1918.

33 See the relevant date at “Kagohl 3 War Diary” as well as at Castle, Zeppelin Raids, Gothas and ‘Giants’.”

34 See Palmer’s R.F.C. Training Transfer Card and his Pilot’s Flying Log Book. Further information on Palmer’s flying is taken from his Pilot’s Flying Log Book.

35 Here and later, Palmer gives the serial number of this plane as [B]9993, which, according to Robertson, British Military Aircraft Serials 1878–1987, pp. 28 (9993) and 36 (B9993), was a B.E.2c.

36 Cablegram 726-S (March 13, 1918).

37 Cablegram 955-R.

38 Cablegram 874-S.

39 See Palmer’s R.F.C. Training Transfer Card, where the recommendation is dated May 8, 1918. The recommendation seems already to have been made, undated, on the same page, by Capt. Cyril Jameson Truran of B flight, No. 50 Squadron.

40 McAndrew, “Special Orders No. 205.”

41 See Palmer’s R.F.C. Training Transfer Card. A letter from Fleet to Benson dated May 31 [1918] in the Leslie A. A. Benson Collection, 1917-1919, indicates that Knight, Mooney, and Maloney also went at this time to Thetford.

42 See Benedict, “Special orders No. 192” and Harbord, “Special Order No. 148” regarding Beebe’s assignment to and away from the 2nd A.I.C. And see Goettler’s diary for late July and early August, which records when he, Beebe, and others were actually at Tours.

42a Carol Palmer, private communication.

43 On U.S. pilot books, see “Flight log books for American pilots in WWI.”

44 Palmer, letter dated September 30, 1918.

45 Sloan, Wings of Honor, p. 387. Squadron rosters for the 85th in Gorrell (C.5, E.9, and E.27) do not provide assignment dates; I do not know what Sloan’s source was.

46 Flanagan, “An Observer with the 85th Aero Squadron,” p. 168. Flanagan inferred that the anonymous diary was written by Blanche; further research using information unavailable to Flanagan in 1982 confirms this identification.

47 Ibid., pp. 169– 70 (entry for October 21, 1918).

48 Ibid., p. 172 (entries for November 4 and 7, 1918).

49 Ibid., pp. 172–73 (entry for November 10, 1918).

50 Ibid., p. 173 (entry for November 11, 1918).

51 War Department. Office of the Quartermaster General, Army Transport Service, Lists of Incoming Passengers, 1917 – 1938, Passenger list, U.S.S. Aeolus.

52 “Bob Palmer is Here from New York”; Ancestry.com, 1940 United States Federal Census, record for Robert T. Palmer; and Ancestry.com, U.S., World War II Draft Registration Cards, 1942, record for Robert Thomas Palmer.