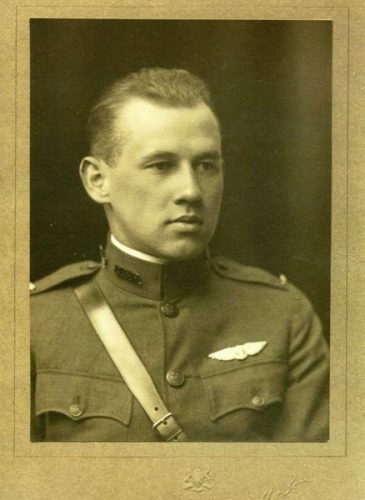

(Muncy, Pennsylvania, October 23, 1892 – near Bapaume, France, August 24, 1918) 1

Oxford & Grantham ✯ Northolt ✯ Croydon ✯ Turnberry, Ayr, ferrying ✯ France & No. 56 Squadron ✯ Leave, No. 1 Squadron ✯ August 24, 1918

Ritter’s paternal forebears came to Pennsylvania from Germany sometime before the Revolutionary War, and at least one of his Ritter ancestors served in that war. His great-grandfather Ritter settled near what would become the town of Muncy in Lycoming County, Pennsylvania, in the first part of the nineteenth century. Ritter’s father, William A. Ritter, was a machinist, eventually a foreman in a machinery manufacturing company in Muncy; in 1889 he married Abbie Edwards Scull. She was from Cape May, New Jersey, where her family had roots going back to the eighteenth century. The couple had four children, all boys; the oldest died in infancy; Roland Hammond Ritter was the next oldest.2

Ritter attended school in Muncy before going on to study mechanical engineering at the Drexel Institute in Philadelphia, graduating in 1916. In his senior year he was president of the Drexel Club of Engineers and manager of the baseball team.3 This boded well for his chances of being selected for the Aviation Section of the Signal Corps, which sought leadership skill, academic excellence, and athletic ability.

When Ritter registered for the draft in early June 1917, he was in Philadelphia, working as plant superintendent for the National Metal Edge Box Company.4 He enlisted on June 19, 1917, and evidently applied to and was accepted by the A.S.S.C.5 By the end of the month he was in Columbus, Ohio, attending ground school at the School of Military Aeronautics at Ohio State University. It was understood that the top students in the class would go to France for advanced training. However, shortly before Ritter’s Squadron 7 graduated from ground school on August 25, 1917, they were offered the option of continuing their training in Italy. Ritter was one of eighteen from this class who—in the words of his classmate, Parr Hooper—“put our names down for the Italian Front.”6 “Everybody is getting very enthusiastic for Italy. All the jokes, remarks, & songs have shifted from French girls to Italian girls.”7

The men were at loose ends for a time after graduation, able to visit home and pull together the clothing and equipment they would need for going overseas. In early September they reported to the aviation field at Mineola on Long Island to “hurry up and wait.” Finally, on September 18, 1917, as Ritter recounted in a letter home, they left Mineola “at about 6:30 a.m. Marched fully equipt to Garden City station on Long Island R.R. then took a special train to Long Island City where we boarded a small boat which took us down to the Cunard pier at 9th St. . . . We boarded our boat about 9:00 and by 11:15 we were started down the river.”8

Their “boat,” the R.M.S. Carmania, sailed north to Halifax where she joined a convoy for the Atlantic crossing. The 150 cadets of the self-styled “Italian detachment” were travelling first class and, as Ritter noted, “it is just like a big hotel and a vacation. Absolutely nothing to do except eat sleep and attend boat drill.”9 Ritter initially experienced some mild sea sickness and on at least one occasion had to leave an Italian lesson being conducted by Fiorello La Guardia rather abruptly. By the end of the week, however, he had “gotten over all ideas of seasickness and . . . have been working pretty hard at Italian. I think that by the end of six months we will be able to handle it pretty well.”10 By this time the convoy had entered the danger zone, and the men of the detachment were taking turns on submarine watch. Fortunately, the convoy encountered no subs, and the Carmania docked safe at Liverpool on October 2, 1917.

Oxford and Grantham

Murton Llewellyn Campbell, who had been a class behind Ritter at O.S.U., wrote in his diary on October 2, 1917: “Left the old Carmania at 10:10 a.m. and took a train for Oxford, England. . . . It took until 5:30 to get to Oxford. . . . We had mess at 7:30 and it was fine: soup, potatoes, beans, one big fish, bread, and pudding. . . . We were informed that we were not going to Italy—worse luck.” For whatever reason, it had been decided that the detachment would remain in England and attend ground school (again) at the Royal Flying Corps’s No. 2 School of Military Aeronautics at Oxford University.11

The men spent their first night in England in various Oxford colleges; the next day they were given more permanent assignments in Christ Church College and The Queen’s College. Ritter and Campbell shared a room in Christ Church, along with Allison Henderson Chapin and Charles William Harold Douglass, both of whom been in Ritter’s ground school class. Campbell noted in his diary that they were “enjoying a very comfortable place.”12 This changed later in the month when, in the aftermath of some high spirited and bibulous celebrations by American cadets of both the first Oxford detachment (which had arrived in early September) and the second, the British insisted on moving all the Americans into a single college, Exeter, which was generally regarded as a step down.13 Towards the end of the month Ritter wrote home that “Occasionally we run out of wood and coal which means that you bundle up in your overcoat and wait for bedtime.”14

Because at Oxford they were revisiting topics already covered in U.S. ground schools—albeit now with R.F.C. instructors who had had first-hand experience of war and flying—the men could coast to some extent and had leisure to enjoy the amenities of Oxford and the surrounding countryside. Both Ritter and Campbell record an outing on October 28, 1917, when they, along with Chapin, walked to Abbington, about five miles south-southwest of Oxford: “On the way over we stopped at a farmhouse and tried to buy some chestnuts. When they found that we were Americans they gave us about 6 pounds of the biggest chestnuts you ever saw.”15 The next evening, according to Campbell, “We roasted some chestnuts tonight by our cozy little fire. Dug, Chap, [Stanley Coooper] Kerk and Rit were the bunch and a good one too. Hope I am in Flying School with them.”16

Meanwhile “It was reported last week that we would be posted to-day but to-day is over and nothing has happened”—this from Ritter’s letter of October 29, 1917. Rumors such as this were rife, the result, in part, of the uncertainty among the powers that were as to what would or could be done with the men. The number of openings at R.F.C. training squadrons lagged far behind what was hoped for and promised. Finally, on November 3, 1917, most of the men, including Ritter, were sent to a machine gunnery school at Harrowby Camp, located just northeast of Grantham in Lincolnshire, while a fortunate few, mainly men who had had some flying in the States, were to go to Stamford for flying instruction. “We left twenty of the men who have been doing flying. They are posted to squadrons tomorrow. Our sergeant [Elliott White Springs] was among them so [Joseph Frederick] Stillman was elected.”17

Many of the men sent to Grantham found it frustrating that their flight training was yet again delayed, but Ritter, in a letter home the day after his arrival at Grantham, focused on improved living conditions and status: “This is the first time since we got off the boat that we are all really happy. . . . We have the regular officer’s mess and rank as officers. We salute no one under rank of Major. . . . We have nine men in a hut with a batman or servant to shine our shoes, belts etc and make our beds and bring wash water etc. It’s quite handy and a lot different from what we had at Oxford. . . . We have a fine big lounge room with plenty of heat. Our barracks also have a stove which makes it a lot more comfortable. We nearly froze at Oxford all the time. The food is great too.”18

That same day Ritter and a number of other men from the detachment went to a nearby flying field “to watch them flying. As many as 15 were in the air together.” He goes on, rather ominously: “Since I got back word came in that one fellow crashed and was killed.”19

Ten days later, as the men were finishing up a two-week course on the Vickers gun, they learned that there were openings for fifty men at flying schools. Hooper wrote home on November 14, 1917: “This morning when we fell in to go on the range, Capt. [Stephen Leslie] Hibbard . . . read out the 50 names of the men who go to flying schools next Monday. I had the best of luck. I am going, and with what I think are the very best fellows. Those who are with me and were in my squad at Columbus are Stillman (who is the cadet C.O. of this whole detachment now), [Guy Samuel King] Wheeler and Ritter. There are ten of us going to the flying school at Doncaster (60 mi. north of here).”

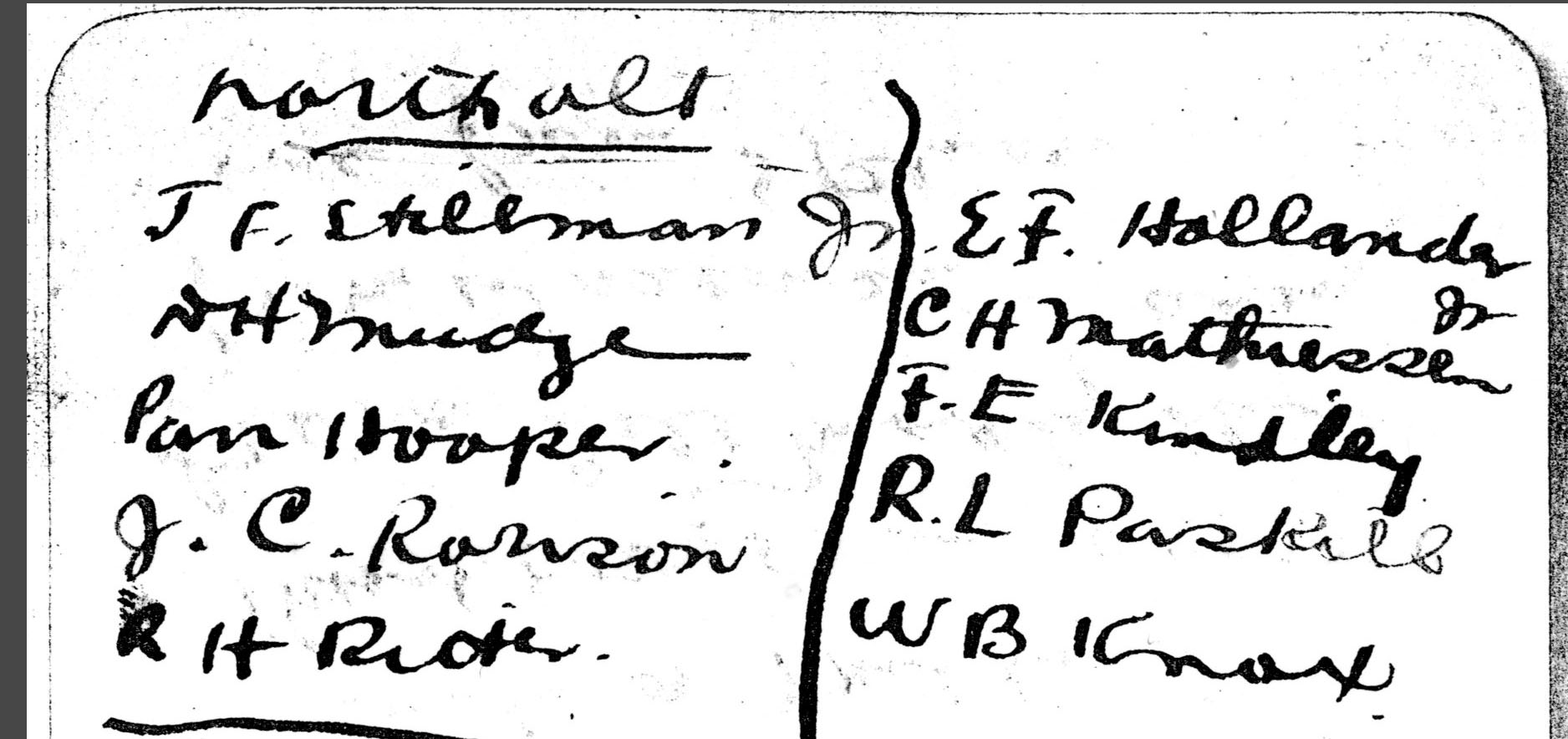

No. 2 T.S. Northolt

Inevitably, there were changes. Wheeler was stuck another two weeks at Grantham. Ritter’s Oxford roommates Douglass and Campbell went to Doncaster, but Hooper, Ritter, Stillman, and seven others (including John Chadbourn Rorison and Dudley Hersey Mudge from the class behind them at O.S.U.) were posted to training squadrons at Northolt aerodrome in Ruislip on the northwest outskirts of London. Hooper recalls that they “packed up Sunday evening [November 18, 1917] and loaded our luggage on motor lurries [sic] at sunrise Monday. The train for London left at 7:30. We had a 1st class compartment and read the papers and watched the scenery. We arrived at King’s Cross Station unexpectedly soon 10:45. Fred [Stillman] and Dud Mudge went up to Paddington Station with our luggage on horse drawn busses. Rorison and ‘Rit’ and I started out to see London before we took the train for Northolt at 1:57 from Paddington,” arriving at Northolt about 4:30.20 Hooper and Ritter, assigned to No. 2 Training Squadron, shared a room in one of the huts, where there were “2 officers to a room and a man servant to each hut of 6 rooms.”21

Ritter noted that they were “about eight miles from London. I guess we can go in [to] town about when we please, providing of course there are no classes.”22 This they did the Wednesday after they arrived. Hooper, finishing up a letter that evening around 6:30, reported that: “I am in the Piccadilly Hotel where I am going to the Grill Room and have dinner with Fred Stillman, Dud Mudge and Robert [sic] Ritter. Dud has just come. I will mail this,” adding “We are all going to the best show tonight.”23 Hooper was disappointed by “Chu Chin Chow,” but does not mention what his companions thought of it.

Back at the Northolt aerodrome, Ritter reviewed the planes there, including “a giant biplane . . . the largest in the world.” This was the “Kennedy Giant,” designed by Chessborough J. H. MacKenzie-Kennedy. “So far it has never been able to get off the ground. It is an immense thing. . . . There are a good many Bristol Scouts here too. They are the swift fighters.” Finally, “The machines in the elementary school here are pushers, that is, the propellar [sic] is in back of the engin [sic] and the pilot sits out front. They are old type machines and are very hard to fly.”24 These were Maurice Farman S.11 Shorthorns, known as “Rumpties,” which had been developed before the war and used on the Western Front into 1915; in late 1917 they were ubiquitous at elementary training squadrons.

It was windy the first two days the men were at Northolt, but on November 22, 1917, Hooper was able to make his first flight, and Ritter’s experience was probably similar. They took time off a week later, on Thanksgiving Day (when, in any case there was no flying because of wind) to go once again in to London, Hooper early, followed by Ritter and a Canadian friend they had made at No. 2 T.S., Bishop Arlington Wilson. They enjoyed lunch at a restaurant and then played tourist in the afternoon. While Hooper headed back to Ruislip on his own, “Rit and Bishop stayed in town to dinner and a show.”25

Flying training continued to proceed slowly at Northolt because of poor weather. However, on December 3, 1917, Ritter and Hooper’s fellow second Oxford detachment member Conrad Henry Matthiessen went up solo; Hooper lobbied his instructor, who was persuaded to let him fly solo December 4, 1917.26 And two days later, after four hours of flying dual with an instructor in Rumpties, Ritter was able to fly solo; he made two flights that day, with a “fair landing” and a “good landing.”27 By this time, Hooper had “twenty minutes more to fly here and then I am ready and allowed to go to a scout squadron. However my instructor said that if I wanted to wait for my mate ‘Rit’ I could, and fly rumpties here as much as I please while waiting. Rit did his first solo today, and we only have to do 4 hours solo in rumpties before we go to the more advanced squadron, so I am figuring on staying here until we can both go together.”28

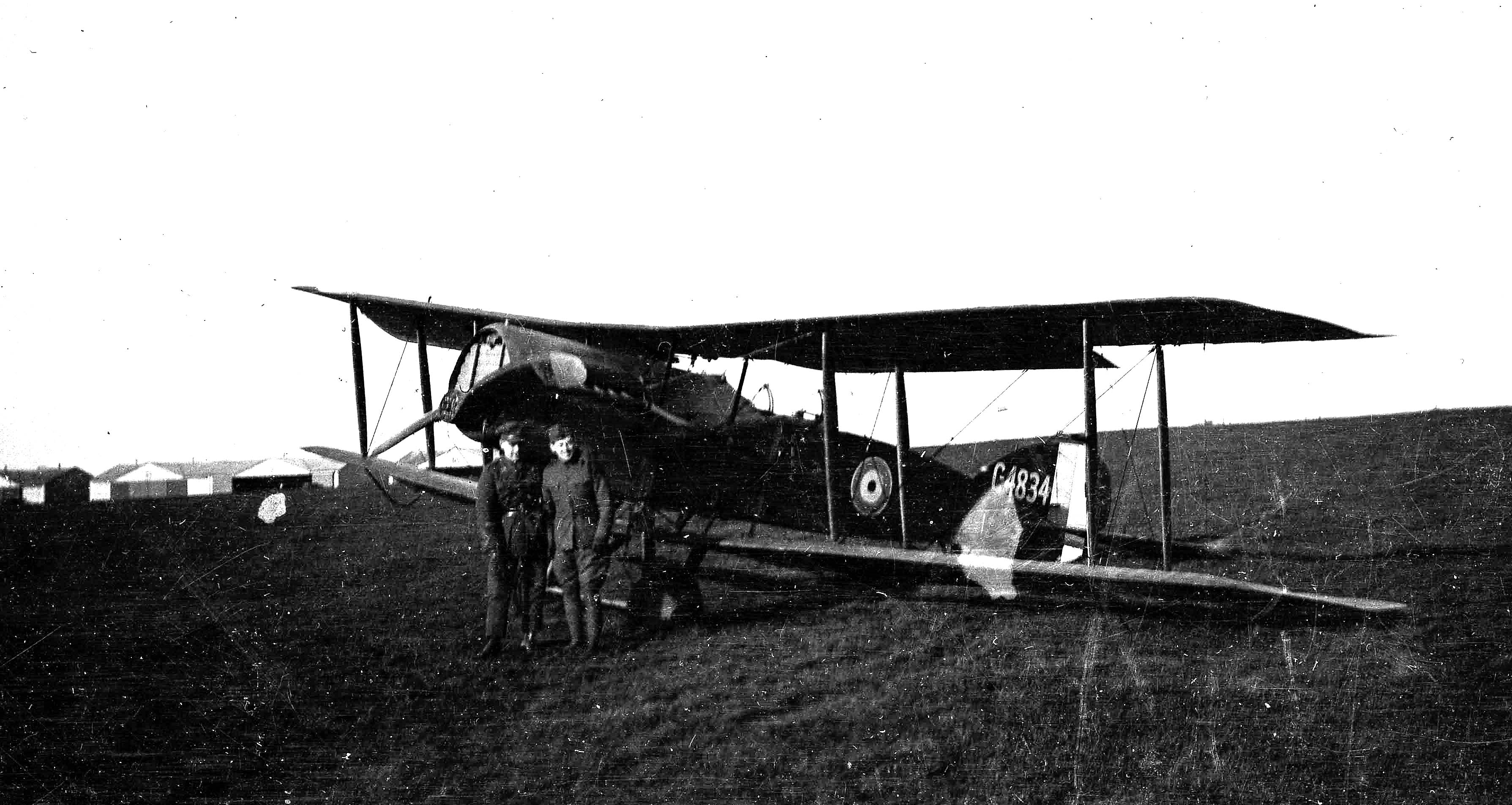

Hooper remained at Northolt until December 18, 1917, and it is apparent that Ritter was also still there—Hooper took a photo of him and Wilson in front of a Bristol Fighter at Northolt on December 15, 1917.

Twice in December Hooper, Ritter, and Wilson met up in London. Hooper had posting leave starting the morning of December 12, 1917, and, after a visit to the Science Museum, “went to the Regent Palace Hotel where I was to meet Rit and Bishop. We got together and went out to dinner. Then we went to the theater to see ‘The Thirteenth Chair.’ It was a poor detective drama. We spent the night at the Regent Palace Hotel and enjoyed the luxuries of beds, sheets, bath and all to the limit. After breakfast we went out into town.”29 Four days later Hooper was in London again; in the afternoon, he “went back to Paddington where I met ‘Bish’ & ‘Rit,’ and the three of us went to call on the McLellands”—a Canadian family, probably friends of Wilson’s—“We arrived at tea time. . . . They have a very nice home and it was a fine party. ‘Bish,’ ‘Rit,’ . . . and I stayed for dinner and until 10 o’clock. . . . As there was no late train out to Northolt Sunday night we went back to the Regent Palace and enjoyed its luxuries again. ‘Bish’ was orderly officer for Monday and I had to report to the adjutant to inquire about my posting so we had to leave early before breakfast. ‘Rit’ stayed and had breakfast served to him in bed.”30

On Tuesday (December 18, 1917), Hooper was posted to No. 56 Training Squadron at London Colney; four other men of the ten who had been assigned to Northolt together were also assigned to London Colney. Ritter, however, was posted to No. 40 Training Squadron at Croydon on London’s southern outskirts, probably, like Field Eugene Kindley, on December 18, 1917, although it is possible that, like Walter Burnside Knox, he went initially to No. 65 T.S. at Dover before being reassigned to Croydon.31 All of the men who had been assigned together to Northolt, with the exception of Mudge, who had been rendered hors de combat by a training accident there, were on the path to becoming scout pilots.32

Hooper and Ritter apparently met up in London yet again in early January 1918 after their respective postings, but the letter from Hooper that presumably has a full description of this encounter went missing.33 Ritter evidently also wrote home around the turn of the year, but that letter is not among those I have seen and may also have gone astray.

No. 40 T.S. Croydon

It comes as a surprise, then, to read the opening of Ritter’s letter of January 13, 1918, written on 40 T.S., Croydon, letterhead: “I thought probably I ought to write and supplement my letter from the hospital. I finally was discharged from H— yesterday morning.” He does not say what he was being treated for, but in his December 7, 1917, letter he noted that “I have a bum foot, . . . I sprained the big toe joint at Oxford and it doesn’t seem to get better,” and it was perhaps this injury that landed him in hospital.

Ritter returned to 40 T.S. ready to resume training. In his January 13, 1918, letter he describes having gone up with an instructor that morning; their engine failed, and they crashed in a ploughed field. The plane was wrecked—Ritter promises to “send a small piece of the prop. home as a souvenir”—but Ritter’s account indicates that he and his instructor suffered only minor injuries, as does the absence of a casualty card. Their plane was almost certainly an Avro, the two-seater training plane used at many squadrons, including 40 T.S., where men were in line to become scout pilots.

Winter weather limited flying opportunities. In the latter part of January 1918 Ritter wrote home that “Last week I only had 55 minutes. So far I have had about 4½ hrs. dual and am ready for solo as soon as we get a good day. We have been practicing stunts for the last week or so.”34 The previous week’s flying included “a most wonderful trip above the clouds.” Ritter goes on to write about his overall progress and prospects: “We were notified the other day that we get our commissions as soon as we do our 20 hrs solo. I have 4 hrs now [on Rumpties at Northolt], so if the weather is at all decent I ought to get my pips and wings up next month.” Ritter also notes having received a letter from his brother Fred who mentioned that their parents are “worrying considerably about” him—perhaps the result of Ritter’s detailed account of his January 13, 1918, crash—and Ritter is at pains to reassure them: “You all think that flying is so dangerous but if you could see how the machines are thrown about in the air and how badly they can crash without hurting the pilot, you would agree that it is not.”

Ritter’s next letter, from early February, would not have put their minds at ease. While maintaining that “it is safer by far too [sic] fly, carefully of course, than it is to chase a Ford around the hills the way we used to do,” he also mentions that “We had a couple of fatal accidents too the first of the week. Also [Roy Olin] Garver who was at Columbus . . . killed himself last Tues.”35 All three of these accidents had been on Sopwith Camels, planes that, because of their engine torque, were notoriously tricky to fly for new pilots.36 Ritter was at this point, however, still flying and learning to stunt on Avros, as “Our flight has all the Scouts [Sopwith Pups & Camels] in shop.”37

Conditions for flying were improving, and over the next two weeks or so, Ritter was able to get in enough solo flying to reach the twenty hours required for his commission, as he reported home in his letter of February 19, 1918. The recommendation having been forwarded to Pershing, Pershing included it in a cable to Washington dated February 28, 1918; the confirmation came back dated March 11, 1918.38 In the same letter of February 19, 1918, Ritter notes having made his first flight in a Camel that day, and also having “Had my first forced landing today. The engine conked while I was down low and gave me no alternative but to land. Fortunately I found a nice field and landed safely. It was the nicest job I’ve done thi[s] far. Some mechanics came and got the engine started for me and I got off the field and back home without any more trouble. As soon as I got back I climbed in the Camel and made a good show.” Presumably not to worry his parents, Ritter does not mention his crash landing three days previously. He was working to fulfill the requirements for graduating from the intermediate stage of R.F.C. training which included a “height test”—flying at 8,000 feet for fifteen minutes. First Oxford detachment member Duerson Knight, also at Croydon, noted in his diary having done his height test on February 16, 1918, and then goes on: “Ritter tried the test and crashed on the aerodome [sic] putting one pup out of business for a while.”

Another graduation requirement was a cross-country flight, which Ritter anticipated doing “the first decent day”39—Knight made his on February 26, 1918, flying from Croydon to Wye and back; Ritter may have done the same, or may have flown instead to Dover and back.40 In any case, Ritter reports to his brother Fred in a letter dated March 3, 1918, that he had completed his training at Croydon, having evidently fulfilled all his graduation requirements.

It is perhaps worth noting that in his December 7, 1917, letter Ritter had promised to send some pictures home, particularly as he has “to have one taken for some British Aero Club to which we are admitted.” The Royal Aero Club had trained pilots, including military pilots, in Britain until 1915, conferring an RAeC Aviator’s Certificate on successful graduates. When government military schools took over in 1915, graduating pilots were eligible to take an RAeC Aviator’s Certificate, but logistics and cost sometimes made it impracticable. This seems to have been the case for Ritter, who, along with most or all of his fellow second Oxford detachment members, apparently did not follow through on “taking his ticket,” despite having planned to have the photo taken for the RAeC certificate. 41

Ritter goes on in his letter to his brother to report being pleased with his experience flying Camels: “It is encouraging to feel that you can fly fairly well the machine so many have killed themselves on. They are hard to fly and very tricky but they go some.” This apparently prompts him to mention to Fred that “Ten of our fellows have gone west already but of course don’t say anything of it when you write home.”42

Turnberry, Ayr, Ferrying

Ritter’s next posting was to the No. 2 Auxiliary School of Aerial Gunnery at Turnberry on the west coast of Scotland. He probably went there at about the same time as Knight, who was ordered to Turnberry on March 8, 1918, and apparently arrived the next day.43 When Hooper encountered Ritter at Turnberry on March 22, 1918, he described Ritter as “just finishing up here.”44

March 22, 1918, may have been the day that Ritter was finally sworn in as a first lieutenant. Two days previously he reported to his brother Billie that “I just got a telegram from our Colonel in London asking if I would accept first Lieut. Commission. Got the appointment Mar 11—a bit late but certainly better late than never. Will be sworn in probably tomorrow or next day.” In this same letter Ritter writes that “I will put a clipping in letter showing a picture of my last roommate who was unlucky. He makes the fourth I have had to go out. He died as all others, took one too many chances and didn’t get away with it.” In the absence of the clipping, I cannot identify the man in question with certainty. But there were two fatal air accidents at Turnberry during Ritter’s time there; both occurred on March 17, 1918. Edwin Charles Hull and Robert Schermerhorn McNair were each flying a Camel that day and each got into a spin too close to the ground.45 Either or both could have roomed with Ritter at the Turnberry Hotel where the pilots in training were housed. The others to whom Ritter alludes may have been Garver and Stillman, his classmates at O.S.U., both of whom had died as a result of air accidents.

Shortly after encountering Hooper on March 22, 1918, Ritter would have made the short journey slightly farther up the coast to Ayr for his final training at the No. 1 School of Aerial Fighting. On March 27, 1918, he wrote home on Wellington House, Ayr, letterhead: “I haven’t finished the course here yet but they are sending men over every day and I am among the next to leave I think. I am glad too because I’m getting fed up with training.” The need for men and planes had increased dramatically with the opening of the German Spring Offensive on March 21, 1918, hastening the transfer of men from training to active duty posts.

The evening of Sunday, March 31, 1918, before finishing their course, Ritter and Knight were told to report to “Mason’s Yard” in London, where training headquarters of the R.F.C.—as of April 1, 1918, the R.A.F.— was located.46 But “Instead of being sent overseas, [we] were put on a job taking machine[s] to France and bringing old ones back.”47 The morning of April 3, 1918, the two pilots set out, presumably by train, for “better not say where” (Ritter), i.e., Norwich (Knight). Late in the afternoon each took off from Norwich in a Camel (“a dandy new buss,” according to Ritter) which they were to ferry down to Lympne on the south coast of England, the jumping off point for ferrying planes to France. Writing from Eastbourne the next day, Ritter describes how they “were supposed to land up the coast from here and fill up before crossing the channel to France.” It was misty, and they got separated and lost, Ritter ending up in Eastbourne, and Knight slightly farther east along the coast at Lydd. Knight records making it to Lympne the next day, but being delayed there by bad weather; he apparently made his first trip to Marquise on April 7, 1918; Ritter’s experience was probably similar.48

Although Ritter surely wrote many letters home after the one from Eastbourne, those available to me include only one further letter, from early July. It is thus fortunate that Knight continues to mention Ritter in his diary from time to time over the course of April and early May 1918. On April 8, 1918, Knight describes having spent the night at the Orchard Hotel, where the R.A.F.’s Central Despatch Pool was headquartered, and taking the 11:45 for Lincoln. From there he “pushed off at once (5 pm) with Ritter and had a wonderful trip until I reached the Thames.” Once again clouds made navigation difficult, and Knight “lost Ritter.” Poor weather kept Knight from making another trip to France until April 11, 1918; the same may have happened to Ritter. Continuing poor weather meant Knight did not do another ferrying job until April 20, 1918, when apparently (his account is not very clear) eight pilots were charged with ferrying planes from Lincoln in poor weather: “Had a rotten trip and was worried. Ritter & I were the only ones thru out of the eight starters. Pushed across to Marquise and spent the night in Boulogne at the Officers Rest Club.” Two days later, Knight was back at Lincoln “late and although it was dud pushed off with Ritter & Hales.”49 Knight does not refer to Ritter again until he was back in London on April 28, 1918, when he “found Ritter who had had trouble, had come in and go [sic] out for an S.E.5.”

On May 9, 1918, Knight, and presumably Ritter also, learned he was about to be posted overseas; it turned out Hooper was posted at the same time. They spent the morning of May 10, 1918, packing, and then went out together for lunch at the American Officers Club: “We had a fine meal there, fried chicken on a meatless day, and lots of fun. Then Rit and Knight and I went the round of the American war offices and got our passports and identification cards.”50 They got an early breakfast the next morning and set out by train for Folkestone, crossing the Channel that afternoon, and then reporting to the pilots pool at No. 2 A.S.D. at Rang du Fliers.51

The next day, May 12, 1918, Knight wrote in his diary that “On arriving discovered I was posted to No. 1 Squadron and Ritter to No. 56. I was sorry that we could not stick together.” Knight had flown an S.E.5 for the first time while ferrying and thought “they are great”; he put some effort into getting into an S.E.5 squadron.52 Whether Ritter also wanted an S.E.5 squadron rather than one that flew Camels is unknown; in any case, No. 56, like No. 1, flew S.E.5s.

France and No. 56 Squadron

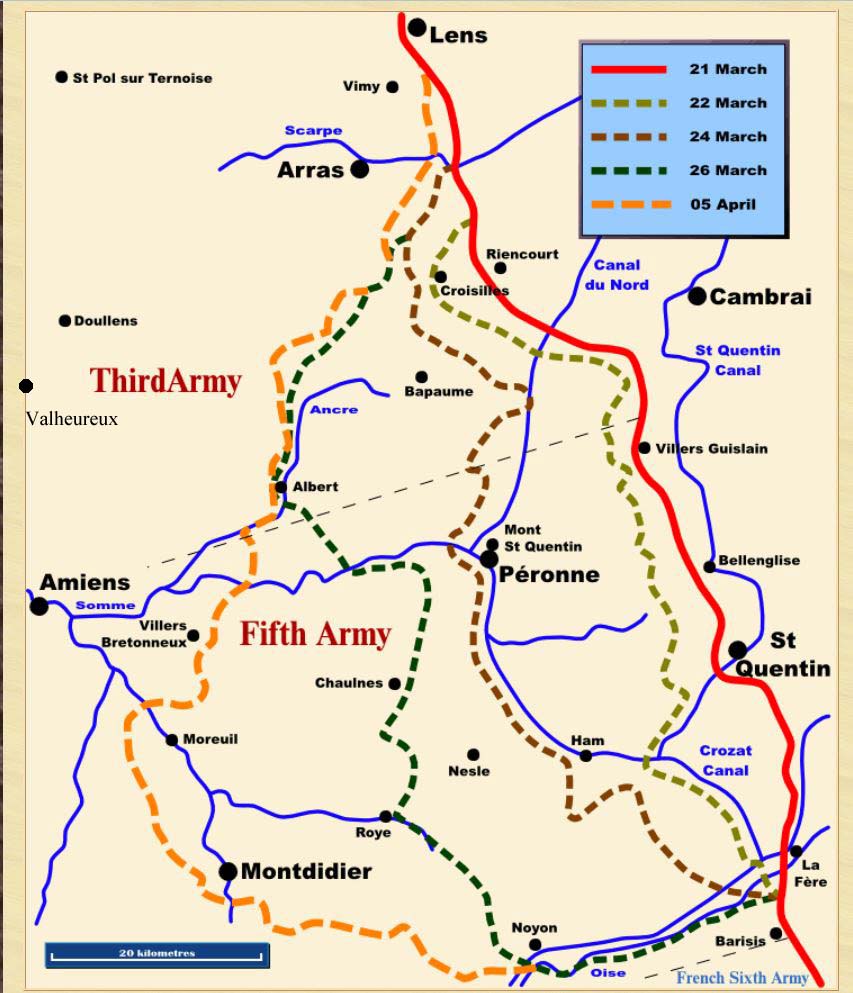

The fine reputation of No. 56 Squadron R.A.F. and its pilots was well established. The first squadron to be equipped with the S.E.5, the best R.F.C. scout plane at the time, 56 deployed to France in April 1917. In June of the same year the squadron upgraded to S.E.5a’s, which had even better speed and climb. In November 1917 No. 56 Squadron was assigned to the R.F.C. Thirteenth Wing, and supported the British Third Army by seeking out and destroying enemy aircraft along the Third Army’s front, roughly from Albert north to Arras.

When the Spring Offensive began, the No. 56 was stationed at Baizieux, about six miles west of Albert. This site became untenable as German forces advanced, and on March 25, 1918, No. 56 relocated to Valheureux, about seventeen miles west-northwest of Albert; it was at Valheureux that Ritter joined the squadron.

Ritter first appears in the squadron record book on May 13, 1918, one of six pilots in training, out of a total roster of twenty-three.53 His time at 56 began inauspiciously. He was one of five pilots who set out at 11:10 on May 14, 1918, on a practice formation flight. Abraham Lawson Cuffe, commander of A flight, was leading; the other pilots were Harold Arthur Sydney Molyneux, Herbert James Mulroy, and the newly appointed squadron commander, Euan James Leslie Warren Gilchrist. They returned to the aerodrome just before noon. Ritter, in S.E.5a B4880, came in second to last and crashed on landing, apparently without doing significant damage to himself or the plane—Fraser Coventry Tarbutt tested it the next day and reported machine and engine “S,” presumably “satisfactory.” Ritter’s crash may just have been bad luck, or it may have been related to the condition of the plane—new pilots typically ended up with the planes the other pilots did not want, and B4880 was in line to be overhauled. Tarbutt had also tested it two days previously and found it “unable to keep up with Patrol, owing to age.”54 It is also possible that flying an old S.E.5a was a challenge to Ritter’s flying skills. He had trained, and trained hard, on Camels, and had only flown S.E.5a’s—presumably new ones—a few times while doing ferry duty.

Be that as it may, Ritter went up again the evening of the same day for another formation practice flight led by Cuffe, this time without mishap. His plane on this flight was B37, which had flown even more hours (168) than B4880 (114) and would also soon be slated for a complete overhaul.55

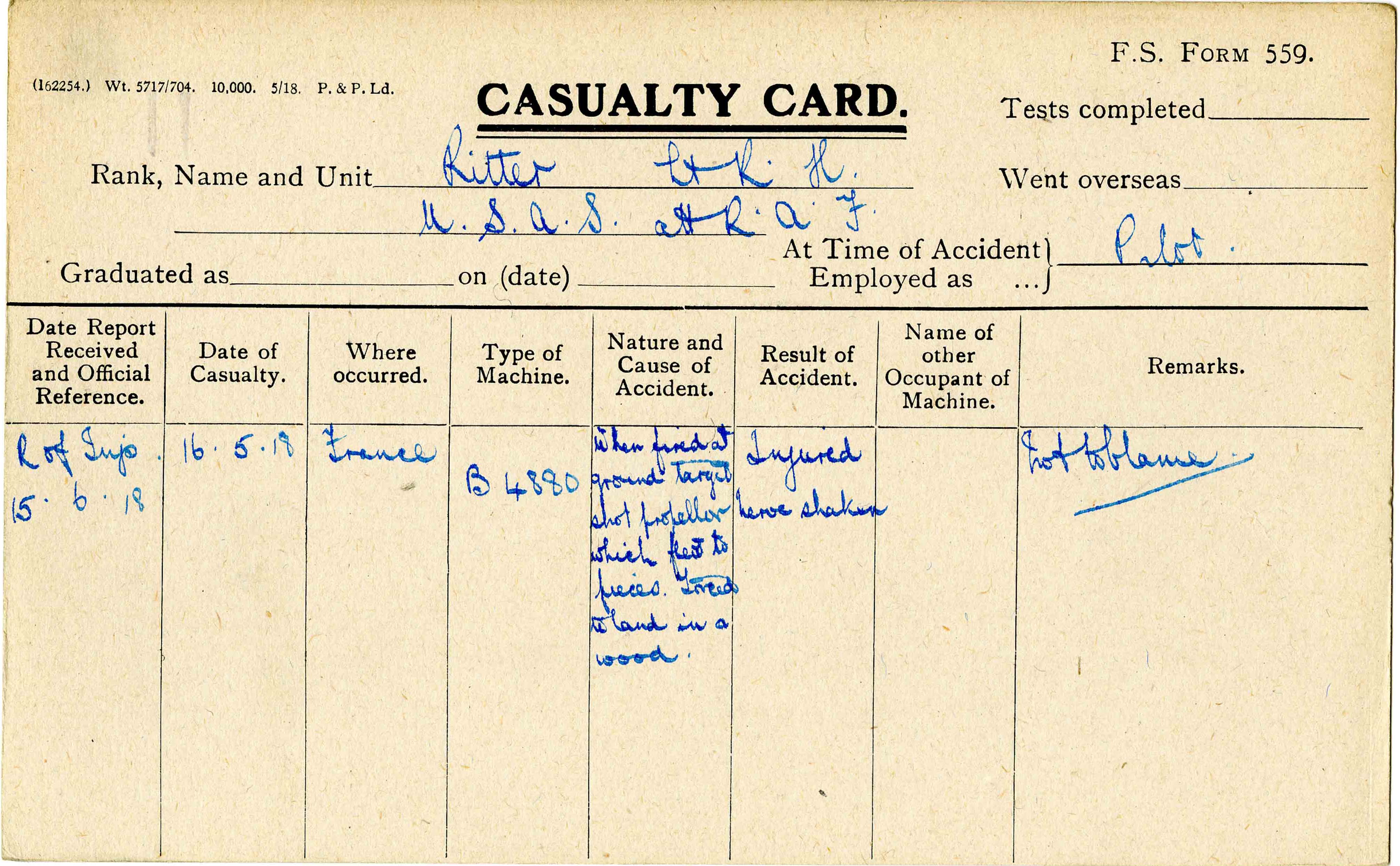

Despite the plane’s shortcomings, Tarbutt flew B4880 on a two hour close offensive patrol led by Cuffe the morning of May 16, 1918, during which three of the five pilots engaged a two-seater over Achiet-le-Grand. 56 It was fortunate that Tarbutt only saw the enemy plane but did not engage with it, for early that evening when Ritter was doing target practice in B4880, he shot his propeller, “which flew to pieces,” and he crashed in a forest about two miles west of the aerodrome.57 The interrupter gear, which should have prevented the gun from firing when the prop was in the way, had evidently malfunctioned. While the casualty report for the badly damaged plane itself states “Pilot unhurt,” the related casualty card describes Ritter as “injured Nerve shaken,” as well as “Not to blame.”58

Ritter did not take part in the practice flights led by Gilchrist over the next two days, but resumed flying the evening of May 19, 1918, when he went up in C9495 with Henry Percival Chubb and Gilchrist for just over half an hour. Over the course of the next two weeks, Ritter went up twelve times, initially seeing the lines and learning the country. On May 26, 1918, he tested the engine in S.E.5a B8238, which Tarbutt had ferried over from 2 A.S.D. to Valheureux about ten days previously, and Ritter began to fly this plane regularly as he continued to practice formation flying, fighting, and firing.

The evening of June 2, 1918, there was another unfortunate incident. Five planes from No. 56 were practicing formation flying with Camels of nearby 201 Squadron. As they were finishing up, the cowling on B8238 came loose, and Ritter was forced to land at 201’s aerodrome at Nœux-lès-Auxi, about eleven miles north-northwest of Valheureux, where his plane “collided with bombstore.” There was no explosion, and Ritter was unhurt, but the plane was badly damaged and, when it was assessed at 2 A.S.D., was found “NWR”—not worth repairing.59

The next day, June 3, 1918, would mark three weeks at No. 56 for Ritter and normally this would mean he would start going over the lines. Had the Third Army front been busier at this time perhaps he would have started flying patrols, but it was fairly quiet, German forces having shifted south in preparation for the Montdidier-Noyon Offensive. After not flying on June 3 and 4, 1918, Ritter resumed training flights on June 5, 1918, “learning the country,” practicing formation flying and fighting. He went up eight times, sometimes in D6098, sometimes in D6088, until his last flight with No. 56 on June 12, 1918, when he did some practice fighting with Cyril Parry. The next day, the squadron record book notes that three pilots are out sick. Alex Revell assumes, and it seems quite reasonable, that the squadron was being visited by Spanish flu.60 On June 14, 1918, the same three plus three more are recorded as sick, and Ritter as in hospital. This is the last mention of Ritter in the squadron record book.

Leave, No. 1 Squadron

It is also the last mention of Ritter, official or otherwise, that I can find until July 17, 1918, when he is once again at No. 2 A.S.D.61 Some of the interim period can be filled in from a letter he wrote home two days later. He mentions having been in hospital and also having been on leave: “I had the time of my life in Monte Carlo. Spent just a week there, two days in Nice and about five days in Paris and then came home nearly a week before my leave was up.” Less cheerfully: “My nerves are all jumpy. . . . I was examined by the Doctor this morning and am going back and try flying again. He wanted me to rest here another week but it is of no use. I would simply fret and worry until I knew what was going to happen. I haven’t much confidence yet but I’m going to try again and if I don’t feel as I should I’m going to give up for a few months. I don’t want to but it will be foolish to stick at it if I can’t be of some real good for I’m sure I can’t be in some other job. I shall hate to take my first flip after not flying for five or six weeks.”62 Ritter in his earlier letters had reassured his family, and presumably also himself, that flying was safe as long as one was careful: his crashes while at No. 56 may have undermined his confidence—his own care and skill could not compensate for equipment failures. His bout of influenza may well also have adversely affected his sense of well-being.

On July 22, 1918, Ritter was posted to No. 1 Squadron.63 It must have been welcome news that he was now finally going to the squadron where Knight had been posted in May. And another second Oxford detachment member, Grady Russell Touchstone, had been assigned to the squadron two days before Ritter.64 Unfortunately, the last entry in Knight’s diary, or at least in the copy I have access to, is dated July 3, 1918, so he provides no information about his experiences No. 1 Squadron during the time Ritter and Touchstone were there.

For three years No. 1 Squadron had been stationed at Bailleul; since the beginning of 1917 it had been part of the 11th (Army) Wing, II Brigade, supporting the British Second Army whose front ran approximately from Houthulst Forest south past Ypres to Nieppe Forest.65 In early 1918 the squadron exchanged its Nieuports for S.E.5a’s. On March 29, 1918, as the scope of the German Spring Offensive became apparent, Bailleul was evacuated and the squadron moved to St.-Marie-Cappel and then, as German forces pushed west on the Second Army front during the Battle of Lys, to Clairmarais South, about twenty miles west of Bailleul and of the lines.

Ritter’s name appears for the first time in the No. 1 Squadron record book on July 22, 1918; he and Touchstone are the two men in the list of pilots “not available for war flying” out of a total of twenty-one pilots (including two on leave).65a Ritter was once again going to have to go through the squadron orientation and training that had occupied his time at 56. Meanwhile Knight, until he went on leave two days after Ritter arrived, was flying offensive patrols regularly; these were typically not close or line patrols, but rather ones that penetrated some way into German-held territory and often involved bombing selected targets. Ritter and Touchstone did not fly at all until July 28, 1918, when both made brief practice flights; after that came several flights of formation practice.

On August 5, 1918, in anticipation of the Battle of Amiens and the opening of the Hundred Days Offensive on August 8, 1918, the squadron was yet again relocated, this time south to Fienvillers, not far from Valheureux. (The record book has Ritter making the ninety minute flight from Clairmarais to Fienvillers in C6878; this should be D6878.) No 1 Squadron was now part of the Fifty-First Wing, attached to IX (Headquarters) Brigade.66 On August 7, 1918, the pilots of No. 1 Squadron, including Ritter in B8426, practiced formation flying; this would also have been their one chance to familiarize themselves with the area before operational flying.

The next morning, the squadron began war flying as the Battle of Amiens commenced; they escorted bombers, flew offensive patrols, and bombed various targets, including bridges over the Somme as part of the effort to cut off the German retreat.67 Touchstone took part in an offensive patrol, but Ritter did not go over the lines, instead ferrying S.E.5a, D6973, to the squadron from 2 A.S.D.—Wallace Alexander Smart would fly this plane until the end of the war.68 In the meantime, Knight returned from leave, taking part in an offensive patrols on August 9 and 10, 1918. The next day the successful but costly advance on this front was paused, and, amid controversy, it was determined that the Allies would shift their operations to the north, between Albert and Arras, towards Bapaume.69 The proposed new area of attack “was so close to the scene of the Amiens offensive as to make unnecessary any great alterations in the disposition of the air units.”70 No. 1 Squadron remained at Fienvillers.

Regardless of the pause in ground operations, R.A.F. squadrons continued to fly missions. Ritter was taken off the list of pilots in training, and on August 13, 1918, took part in an offensive patrol for the first time; the record book gives no details as to where or to what purpose this two-hour mission involving twelve planes was made; Ritter was flying S.E.5a D6970. The next day, again in D6970, he was one of thirteen on an early morning mission: “Bombers were picked up over the rendezvous and escorted over the objective”71—evidently in the vicinity of Peronne, east of which town Fokker biplanes were sighted at 8:30 as the bombers and their escort returned.

From August 15 through August 18, 1918, there really was a pause in No. 1 Squadron’s operations: they flew only practice and test flights. On August 19, 1918, operational patrols resumed, and Ritter, flying D6970, took part in a mission apparently much like that on August 14, 1918, with activity over Peronne. No missions were flown on August 20, 1918, but on August 21, 1918, the squadron began flying missions in the new battle sector to the north. Both Ritter and Knight took part in the offensive patrol of fourteen planes that set off at about 11:30 that day. Half an hour into the mission, they saw three enemy two-seater planes at 2000 feet in the vicinity of Orvillers (presumably Ovillers-la-Boisselle) just northeast of Albert and attempted to engage them without result—this was presumably Ritter’s first experience of operational aerial combat. Enemy scouts, too far away to engage, were seen in the vicinity of the forest near Havrincourt, east of Bapaume; other place names mentioned in the remarks column for this mission in the record book include Croisilles and Gomiécourt. All pilots returned safely, although one, Graham Wilmot Bellin, having run out of petrol, came in well behind the others.

The same pilots, minus Bellin, went out again at 4 p.m. over approximately the same area, this time, however, flying part of the time at low altitude, as pilots are described as firing rounds on men and a wagon on the Arras–Bapaume Road as well as into Bapaume itself.

At 6:15 the next morning, August 22, 1918, the same pilots, now including Bellin, took off and by 7:20 were again near Bapaume, where they encountered “14 E.A. Scouts (mostly Fokker biplanes) at 11,000 feet.” There was a general engagement, during which Knight shot down a Fokker that was on the tail of one of his fellow S.E.5a’s. Everyone returned safely; one plane, Charles George Pegg’s, had been shot through the emergency tank. It appears, although the copy of the record book I have seen is hard to read in places, that Ritter was continuing to fly D6970. The afternoon mission that day, in which Knight and Ritter participated, was less eventful, but again involved flying in the vicinity of Bapaume; 100 rounds were fired on ground targets.

The Battle of Bapaume commenced very early the next morning, August 23, 1918. Revell notes that “the work of the fighter squadrons was again low level attack”—the particularly dangerous type of flying with which No. 1 Squadron was already familiar—“the attention of all pilots drawn to the importance of taking action against anti-tank guns, which had held up tanks in the fighting at Amiens earlier in the month.”72 And, indeed, during the offensive patrol flown by No. 1 Squadron that day, in which Knight and Ritter both participated, pilots “fired at enemy gun teams moving East along roads on a line E. of Gomiécourt and E. of Bihucourt.”73 Knight’s plane was shot through the petrol tank by anti aircraft fire, but he managed to land at the aerodrome of No. 32 Squadron R.A.F. at La Bellevue.

August 24, 1918

The next day, August 24, 1918, Ritter and Smart were among the teams taking part in an even more dangerous type of mission, one in which pairs of pilots bombed and strafed ground targets.74 They set out at 2:05. According to Smart:

We arranged to go over on top of the clouds to see if there were any huns there. If there were not any we were going to dive through over Bapaume and go down to our straffing. There were no huns about so I dipped my wings and dived straight through the clouds, I came out plumb over Bapaume. I circled round waiting for Ritter, but he did not come through, I went back to the lines and looked for him there but there was no sign of him so I went down to do my ground straffing. . . . when I got back, Ritter had not turned up but he landed about a quarter of an hour after I did, he had missed me when he came out of the clouds, so he had flown to our balloon line and stayed there hoping to pick me up. That was the best thing he could have done because he did not know the country and had done very little time over the lines.75

The squadron record book credits Smart with having dropped bombs and fired on a battery between Le Bucquiere and Beaumetz-lès-Cambrai, and Ritter with bombing and strafing hutments east of Bapaume. Another team set out at the same time as Ritter and Smart, and further teams followed at half hour intervals until, at 5:30, it was Ritter and Smart’s turn again.

We went up again after tea, this time we went over under the clouds, when we got to Bapaume we saw a big formation of huns there, so all the ground strafing machines had stopped work and were climbing to engage the huns. I joined one bunch of camels and SE5 however before we got up to their level the huns had cleared off, so I left the formation to get on with the ground straffing, Ritter did not follow me, he stayed up there along with three other machines, so I went down and shot up the Bapaume Cambrai road. I did my straffing from about a thousand feet this time, there was nothing particularly startling except one or two parties of huns walking along. When I got back Ritter had not returned again but I thought he had probably stayed with the other machines when he found I had left, what happened to him I can’t think, but he was missing I think most probably he got lost and wandered off over hun land.76

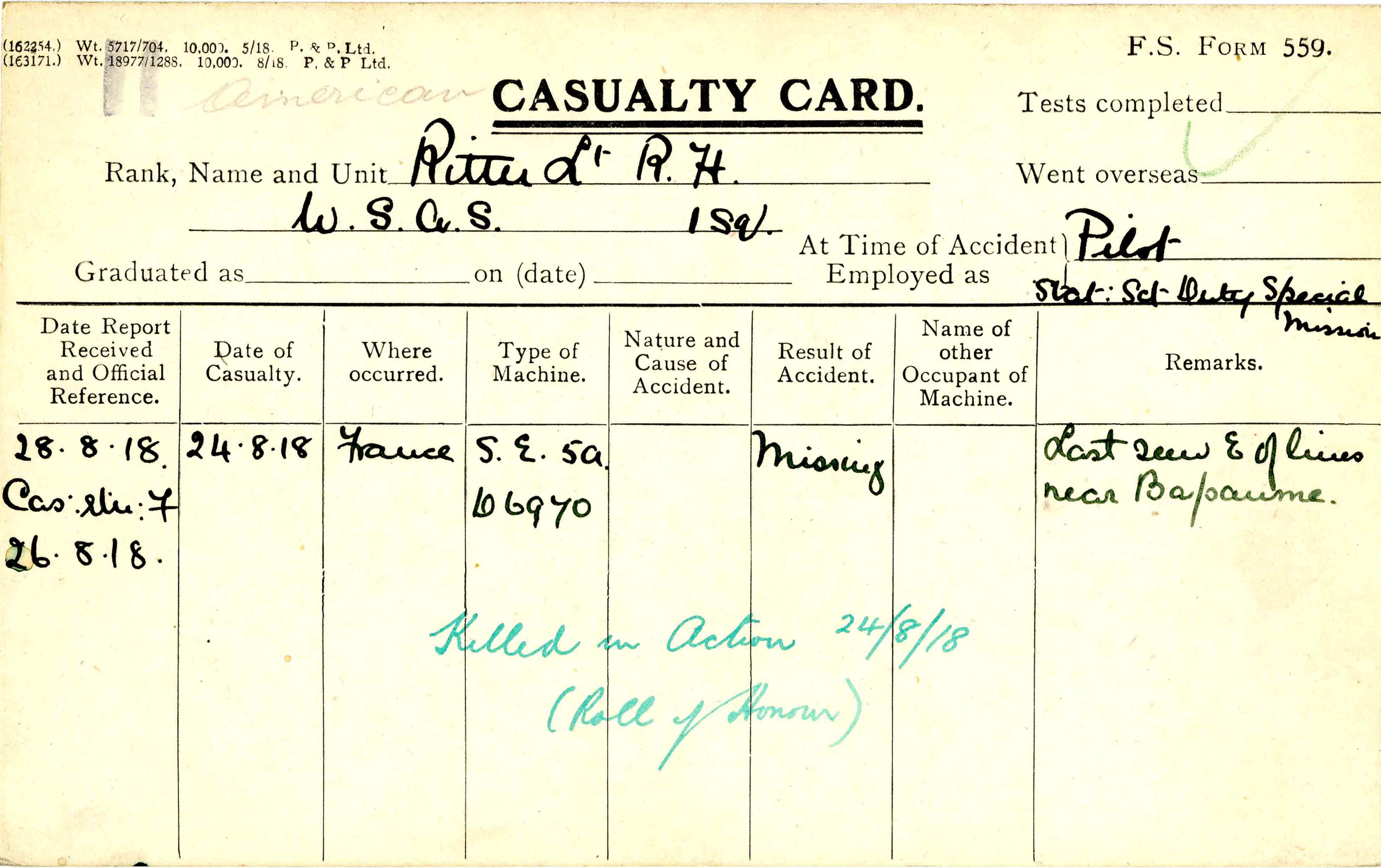

Ritter was for a time listed as missing in action, but at some point it was determined that he had been killed in action on August 24, 1918.77

His body was recovered; he was initially buried in the Mory-Abbey British Military Cemetery, about four miles due north of Bapaume, and later reinterred in the American Somme Cemetery in Bony.78 The American Legion Post in Muncy was named after him. Ritter’s mother was able to visit the grave in 1931.79

mrsmcq February 17, 2023

Notes

(For complete bibliographic entries, please consult the list of works and web pages cited.)

1 Ritter’s place and date of birth are taken from Ancestry.com, U.S., World War I Draft Registration Cards, 1917–1918, record for Roland Hammond Ritter. For his place and date of death, see “Ritter, R.H.” The photo is a detail from the group photo taken of his ground school class at Ohio State University.

2 Information on the Ritter and Scull families is taken from documents available at Ancestry.com.

3 See Drexel Institute, Lexerd 1916, p. 133.

4 See draft registration, cited above.

5 On enlistment, see Ancestry.com, Pennsylvania, U.S., World War I Veterans Service and Compensation Files, 1917-1919, 1934-1948, record for Ralph [sic] Hammond Ritter.

6 Letter from Parr Hooper to his mother (unpublished, in my possession) dated August 17, 1917. Ironically, it would be two men from this class who did not sign up to go to Italy who ended up there: Dewitt Coleman and Thomas Franklin Fielder. Four others from this class went to France: James Frisbee Crankshaw, Harry Daniel Hundley, Arthur Sanford Richards, and Murray Kenneth Guthrie. All six men sailed on September 25, 1917, for England on the Saxonia. See Sloan and Hocutt, “The Real Italian Detachment,” regarding the men in this group.

7 Letter from Hooper to his father (unpublished, in my possession) dated August 18, 1917.

8 Ritter, letter of September 19, continued on September 24 and 29, 1917.

9 Ibid.

10 Ibid.

11 See the explanations for the decision supplied by Hamilton Hadley on p. 4 (286) of his “Foreign Aviation Detachments,” by Geoffrey Dwyer on p. 2 of his “Report on Air Service Flying Training Department in England,” and by Claude E. Duncan as recorded in Sloan and Hocutt, “The Real Italian Detachment,” p. 44.

12 Murton Campbell, diary, October 5, 1917.

13 See Murton Cambpell, diary, October 22, 1917; also the entry for the same date in War Birds.

14 Ritter, letter of October 29, 1917.

15 Ibid.

16 Murton Cambpell, diary, October 29, 1917.

17 Ritter, letter of November 4, 1917.

18 Ibid.

19 Ibid. Frank Lockwood of No. 15 Training Squadron at Spittlegate was flying an R.E.8 when the engine failed; he was unable to recover from the stall and was killed at 4:30 p.m. on November 4, 1917. See “Lockwood, F. (Frank).” Ritter’s fellow second Oxford detachment member, Fremont Cutler Foss, who was still at Spittlegate when the crash occurred, describes it in his diary entry for that day.

20 Hooper, Somewhere in France, letter of November 23, 1917. Ritter, letter of November 20, 1917, gives their arrival time.

21 Hooper, Somewhere in France, letter of November 23, 1917.

22 Ritter, letter of November 20, 1917

23 Hooper, Somewhere in France, letter of November 21, 1917.

24 Ritter, letter of November 20, 1917.

25 Hooper, Somewhere in France, letter of November 29, 1917.

26 Hooper, Somewhere in France, letter of December 4, 1917.

27 Ritter, letter of December 7, 1917.

28 Hooper, Somewhere in France, letter of December 6, 1917.

29 Hooper, Somewhere in France, letter of December 13, 1917.

30 Hooper, Somewhere in France, letter of December 18, 1917.

31 On Kindley, see Ballard, War Bird Ace, p. 24. On Knox, see the National Archives (UK), Royal Air Force officers’ service records 1918–1919, record for Walter Burnside Knox. Ritter’s own R.A.F. service record notes only that he was at Croydon on March 2, 1918, “on graduation.”

32 The tenth man, Rorison, was posted from Northolt to No. 3 T.S. at Shoreham-by-Sea; see Doyle, “War Birds Pictorial.”

33 See Hooper, Somewhere in France, letter #22, dated January 21, 1918, in which he attempts “to finish up No. 21,” which is not extant.

34 Ritter, letter dated either January 24 or 27, 1918. As he remarks of this letter, “My hands are so cold I fear you will hardly be able to read it,” and, indeed, the date is uncharacteristically hard to decipher.

35 Ritter, letter of February 3, 1918.

36 Nineteen-year-old Robert John Fleming was under instruction at 40 T.S. on January 29, 1918, when the Camel he was piloting (B6322) spun into the ground when he made a right-hand turn—apparently a classic Camel accident involving engine torque. Rupert Ernest Neve was an experienced pilot and an instructor at No. 40 T.S. when his “machine [Camel B5235] collapsed in the air presumably from overstrain.” See “Fleming, R.J.,” “Neve, R.E. (Rupert Ernest),” and The National Archives (United Kingdom), Royal Air Force officers’ service records 1918–1919, records for Fleming and Neve.

37 See Knight, diary entry for January 6, 1918, regarding the types of planes at 40 T.S.

38 Cablegrams 660-S and 900-R.

39 Ritter, letter of February 19, 1918

40 See his letter of February 19, 1918 regarding plans for his cross country flight to “Aye [sic? sc. Wye?] or Dover.”

41 Royal Aero Club Aviators’ Certificates from 1910 through 1950 have been digitized at Ancestry.com. On the decline of applications for the certificate, see MacMillan, Into the Blue, pp. 47–48.

42 By this date two members of the first Oxford detachment had been killed, and seven from the second. Perhaps Ritter miscounted, or perhaps he included someone who was not a member of either Oxford detachment.

43 Knight’s diary entry dated “8-4-18” should read “8-3-18.”

44 Hooper, Somewhere in France, letter of March 22, 1918.

45 See “Hull, E.C. (Edwin Charles)” and “McNair, R.S. (Robert Schemehorn) [sic].”

46 Ritter, letter of April 4, 1918; Knight, diary entry for March 31, 1918.

47 Ritter, letter of April 4, 1918.

48 Knight, diary entries for April 4 and 7, 1918. The chronology is somewhat uncertain.

49 Hales was probably John Playford Hales; see The National Archives (United Kingdom), Royal Air Force officers’ service records 1918–1919, record for Hales.

50 Hooper, Somewhere in France, letter of May 9, 1918, continued on May 11, 1918.

51 Knight, diary entry for May 11, 1918.

52 See Knight’s diary entries for May 3 and 9, 1918.

53 RFC/RAF No. 56 Squadron Record Book (1918 April-June). In what follows, information is based on the record book unless otherwise noted. There is a photo of Ritter at 56 with squadron mates Harold Arthur Sydney Molyneux and Walter Henry King Copeland reproduced on p. 306 of Revell’s High in the Empty Blue.

54 See Tarbutt’s report in The National Archives (United Kingdom), Reports on aeroplane and personnel casualties, 11 May 1918 – 20 May 1918; summarized at Pentland, Royal Flying Corps. I am grateful to Pentland for a copy of this report.

55 See the entry for S.E.5a B37 at Pentland, Royal Flying Corps.

56 A “close” offensive patrol is one that does not penetrate far into enemy territory; presumably the same as or very similar to a “line patrol.”

57 “Ritter, R.H.”

58 See report in The National Archives (United Kingdom), Reports on aeroplane and personnel casualties, 11 May 1918 – 20 May 1918; summarized at Pentland, Royal Flying Corps. I am grateful to Pentland for a copy of this report. And see “Ritter, R.H.” (casualty card).

59 See report at The National Archives (United Kingdom), Reports on aeroplane and personnel casualties, 01 June 1918 – 10 June 1918, summarized at Pentland, Royal Flying Corps. I am grateful to Pentland for a copy of this report. And see Pentland, Royal Flying Corps, entries for B8238.

60 Revell, High in the Empty Blue, p. 312.’

61 “Lieut. Roland H Ritter USAS”

62 Ritter, letter of July 19, 1918.

63 “Lieut. Roland H Ritter USAS.”

64 “Lieut. G R Touchstone USAS.” A photo of the three Americans is reproduced among the photos following p. 304 of Revell’s British Single-Seater Fighter Squadrons, as well as in Chapter 2 of O’Connor’s Airfields and Airmen: Cambrai.

65 This is the description of the Second Army front in the late spring and summer of 1918 provided by Blanford, “Sans Escort,” part 1, p. 147.

65a RFC/RAF No. 1. Squadron, record book. In what follows, information is based on the record book unless otherwise noted.

66 See the entry for No. 51 Wing in Sturtivant, Hamlin, and Halley, Royal Air Force Flying Training and Support Units.

67 On bridge bombing, see Jones, The War in the Air, vol. 6, pp. 440 ff.

68 There is a photo of this plane on its nose in Chapter 2 of O’Connor’s Airfields and Airmen: Cambrai.

69 See Jones, The War in the Air, vol. 6, p. 469; also, Revell, British Single-Seater Fighter Squadrons, p. 295.

70 Jones, The War in the Air, vol. 6, p. 469.

71 RFC/RAF No. 1. Squadron, record book.

72 Revell, British Single-Seater Fighter Squadrons, p. 297.

73 RFC/RAF No. 1. Squadron, record book.

74 From my copy of the record book it appears that Ritter and Smart were the first team to set out. However, the page that lists them is labelled “Sheet 2,” and I find no “Sheet 1.” It may be that missions earlier that day are recorded on a missing sheet.

75 Smart, Flying Diary, August 24th.

76 Ibid.

77 See the relevant entry in Henshaw, The Sky Their Battlefield II, which indicates that Ritter may have been shot down by Otto Könnecke.

78 See “Ritter, Roland H.”

79 See Sewell and Palin, U.S. World War I Mothers’ Pilgrimage, 1929, record for Mrs Abbie S Ritter; and Ancestry.com, New York, Passenger Lists, 1820–1957, record for Abbie S Ritter.