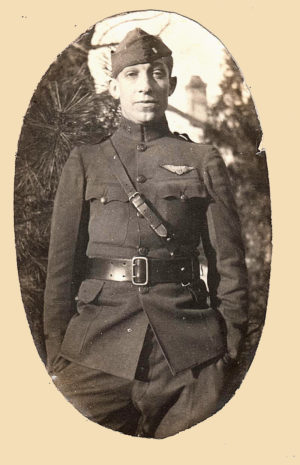

(Fort Smith, Arkansas, March 22, 1894 – Little Rock, Arkansas, December 13, 1937).1

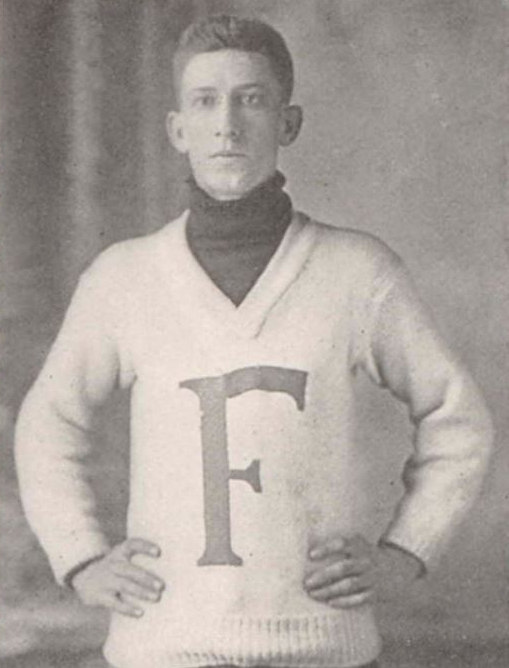

Hardin was the youngest child in a large family. His father, Anonymous Earl Hardin (who usually went by “A. Earl Hardin” or “A. E. Hardin”), was born in Mississippi and studied at the Louisville Medical College in Kentucky before becoming a physician in Fort Smith, Arkansas. Hardin’s mother, Martha Caroline Hardin, née Temple, was from Alabama.2 Hardin excelled at sports, particularly football; he was a star player for the University of Arkansas Razorbacks.3

When Hardin registered for the draft on May 25, 1917, he was at the officers’ training camp at Fort Logan H. Roots near Little Rock. In mid-July Hardin, Eugene Hoy Barksdale, Alexander Miguel Roberts, and Grady Russell Touchstone were among twelve men there who were selected for the aviation corps and sent to ground school at the University of Texas at Austin.4 These four were among ten men from their August 25, 1917, graduating class of about thirty-six who chose or were chosen to continue their training in Italy. They were thus among the 150 men who sailed to England on the Carmania as members of the “Italian detachment.”5 The ship sailed from New York on September 18, 1917, bound initially for Halifax. At Halifax she joined a convoy and set off to cross the Atlantic on September 21, 1917, arriving at Liverpool October 2, 1917. Once in England the men learned that a mix-up had occurred, and that they were to remain there and to go through ground school (again) at the Royal Flying Corps’s No. 2 School of Military Aeronautics at Oxford. The Italian detachment had become the second Oxford detachment (the group of fifty men who had arrived in September constituted the first). A month later, on November 3, 1917, most of the men, including Hardin, went from Oxford to Grantham in Lincolnshire to attend machine gun school at Harrowby Camp.

While fifty of the men at Grantham were sent on to flying schools on November 19, 1917, the rest, including Hardin, continued their course at Harrowby Camp through the end of November. On November 29, 1917, they celebrated Thanksgiving in great style, with many of the men who were already at flying schools coming in to join them. Festivities included a football game between the “Unfits” and the “Hardly Ables” in which Hardin distinguished himself. Walter Chalaire, journalist turned aviator, wrote: “The exhibition of football given by ‘Temp’ Hardin, University of Arkansas, picked for all southwestern quarterback in 1914, was a revelation to the English spectators. His spectacular end runs and the masterful manner in which he piloted the Unfits brot much applause. Time and again he skirted the ends of the Hardly Ables and seemed to delight in giving the stiff arm to Pat Payson. . . . ‘Pat’ blames the war rations for the condition and defeat of his team, while ‘Temp’ attributes the success of the Unfits to the same thing.”6 Hardin appears in photos of the players taken that day.

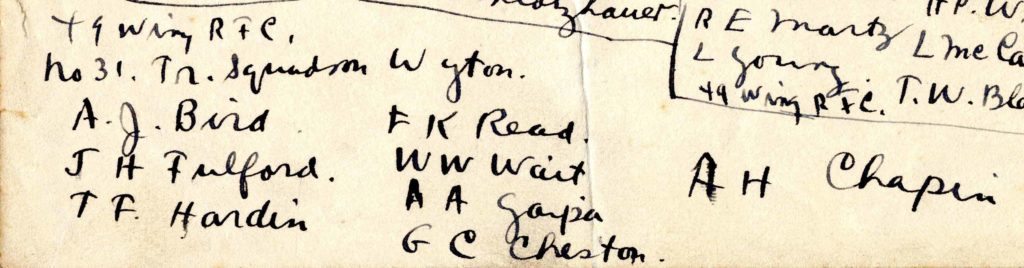

A few days later, on December 3, 1917, according to a list drawn up by Fremont Cutler Foss, Hardin was one of eight men sent from Grantham to No. 31 Training Squadron at Wyton, about fifteen miles northwest of Cambridge (the others were Allen Tracy Bird, Allison Henderson Chapin, Galloway Grinnell Cheston, John Hurtman Fulford, Alfred August Gaipa, Francis Kinloch Read, and William Winslow Wait; Earl Adams, Robert Alexander Anderson, Guy Maynard Baldwin, Thomas John Herbert, and Stanley Cooper Kerk were already at Wyton).7

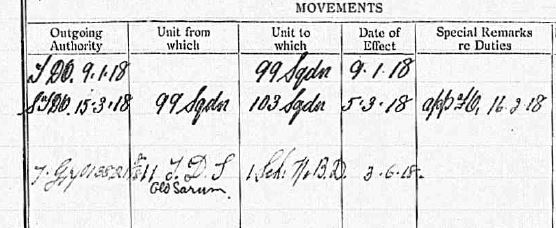

According to his R.A.F. service record, Hardin, after about five weeks at No. 31 T.S., was transferred to No. 99 Squadron at Yatesbury in Wiltshire.8 When No. 99 became an operational bomber squadron in April of 1918, it was equipped with DH.9s, but at the time Hardin joined it in early January 1918, the pilots were still being trained, and they were flying DH.6s and B.E.2e’s.9 By the latter part of February 1918 Hardin had progressed sufficiently in his flight training to be recommended for his commission; the confirming cable was dated March 9, 1918, just a few days after he had been transferred to No. 103 Squadron.10

No. 103, like 99, was a bomber squadron in training; it was stationed at Old Sarum just outside Salisbury. Here Hardin presumably trained on DH.9s.11 At some point he was moved to No. 11 Training Depot Station, also at Old Sarum. On June 3, 1918, he was assigned to No. 1 School of Navigation and Bomb Dropping at nearby Stonehenge.

In early July 1918 orders came that a large group of men, including Hardin and a number of others from the Oxford detachments, was to “proceed from London, England, to Issoudun, France, reporting upon arrival thereat to the Commanding Office for duty in connection with aviation.”12 Issoudun, in the Loire region of central France, was the location of the American 3rd Aviation Instruction Center. Hardin’s stay at the 3rd A.I.C. was brief, for on July 14, 1918, he was put in charge of a small group of men ordered to report “without delay” to the 2nd A.I.C. 12a The next day they accordingly boarded trains to make the journey of about ninety miles north and west to Tours, where the 2nd A.I.C. was located. Six of them went ahead on the 12:24 train, and the four others, including Hardin, following behind with the baggage.12b The journey, which took about six hours, involved changing trains at Vierzon where, of course, the luggage was lost. Harold Ernest Goettler wrote in his diary the next day: “More discouragement when we heard that all this school was for was to train Art[illery] Obs[ervation] [and] that we were to fly these slow sop planes wherever the observer told us to. However after reporting the O.C. admitted he did not know why we were sent here and so to give us something to do is going to let us fly the big French bombers.”12c Things started to look up when the baggage arrived and “Hardin, [Winfield Earl] Sisson, [William Hamlin] Neely and [Thomas Forrest] McCook received a little dual on the old French Breguets that are in camp”; if their experience paralleled Goettler’s, they also flew American “Liberty” DH-4s for the first time at Tours. After three weeks, on August 7, 1918, Hardin, along with McCook, Goettler, and others, was ordered to the 1st Air Depot at Colombey-les-Belles, some 250 miles to the northeast in Lorraine, where the American 1st Army’s sector of the front was located.12d

A few days later, on August 12, 1918, Hardin was assigned to the U.S. 50th Aero Squadron, an observation squadron stationed at that time at Amanty in the Lorraine region. In the next day or so Hardin was joined by fellow second Oxford detachment members Bird and McCook (William Hamlin Neely was assigned in October).13 Other pilots, as well as observers, arrived, and the squadron went about getting its quota of eighteen American built DH-4s with their Liberty engines—six planes for each of three flights.14 The 50th, according to squadron C.O. and historian Daniel Parmelee Morse, was “the second squadron to be equipped with the much-talked-of ‘Liberty’ aeroplanes.”15 These were flown over to Amanty from the American 1st Air Depot at Colombey-les-Belles, and the “work of trimming up the new planes was then started. It took considerable work, as the first Liberties to come through were in need of a considerable amount of repair, owing to the fact that the mechanics at the assembling plants were as yet unaccustomed to the Liberties. . . . A few of the pilots, also, were not given enough time in the schools, so that it was necessary to have some double control instruction by English-trained pilots, who had had considerable time on the English D-H 4, which was exactly like the American D-H 4, except the motor.”16 It is possible that Hardin was among those who served as instructors, as he could well have flown DH.4s while he was at Stonehenge and DH-4s perhaps at Tours.17 Hardin was assigned as one of the 50th’s three flight commanders (the others were McCook and Goettler).18

On September 2, 1918, in preparation for the St. Mihiel offensive, the 50th Aero was ordered from Amanty to Behonne, about thirty miles to the northwest, where they were assigned to work with the 5th Corps of the American First (and at this point only) Army.19 The planes were assembled the next day, and the three flights took off for their new field the afternoon of September 4, 1918. The move was somewhat costly: Goettler records that three planes were written off, including that flown by Hardin, who “had a forced landing on the side of a hill.” He was, however, in good company, as another smashed plane was that of C.O. Daniel Parmelee Morse, who “went over on his nose.”19a

On September 7, 1918, new orders came, and the squadron moved about thirty-five miles back east-southeast to Bicqueley, south of Toul, and was now assigned to work with the First Army’s 1st Corps. The moves were accomplished despite a severe shortage of vehicles, an ongoing problem for the 50th and the American Air Service generally, according to Morse.20

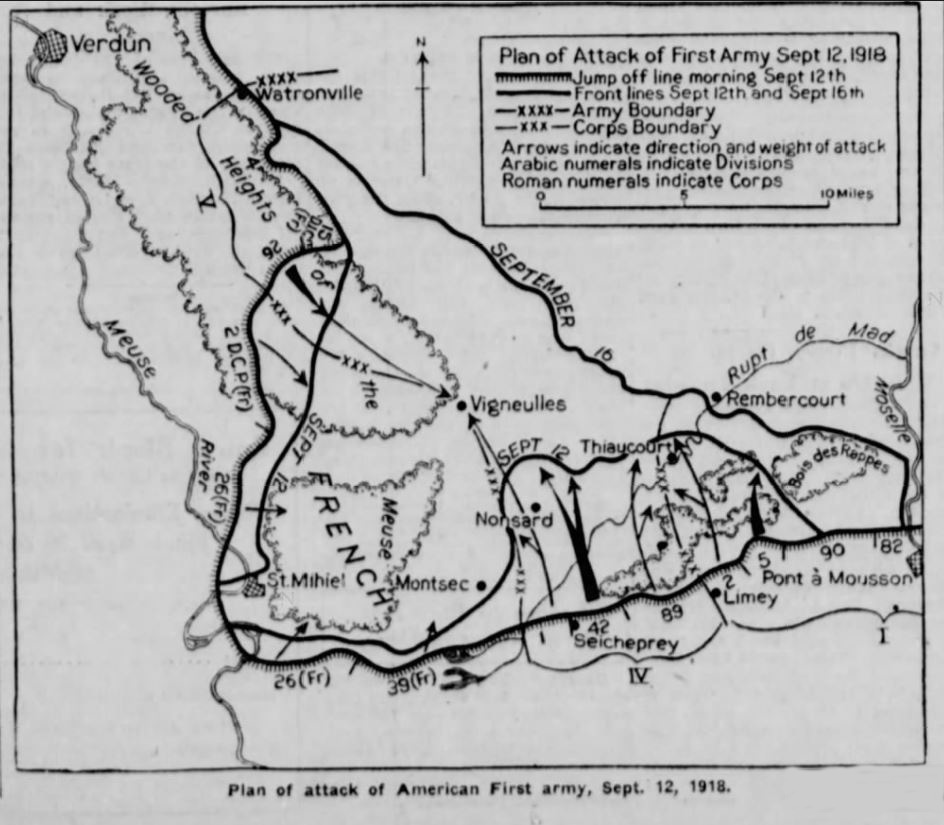

The 50th Aero Squadron was assigned to work with two divisions of the 1st Corps, the 82nd and 90th, which were deployed at the eastern end of the south side of the St. Mihiel salient. They were to carry out reconnaissance of enemy troops and lines as well as to fly contact patrols to locate American ground troops. The latter were necessary when advancing troops could no longer communicate directly with their divisional headquarters; troops were supposed to identify themselves to their air support by means such as flares or panels on the ground; the observation squadron was then to inform headquarters where the troops were.

While the two other American 1st Corps observation squadrons (the 1st and 12th) had taken part in the Battle of Château-Thierry in July, almost none of the pilots and observers of the 50th had seen active service over enemy territory.21 They “were given as much instruction as possible in how it was best to fulfill their missions over the lines. The pilots were given maps to study and later drew maps of the sector the squadron was assigned to. The observers and pilots were instructed how to prepare their map boards in the most valuable way.”22

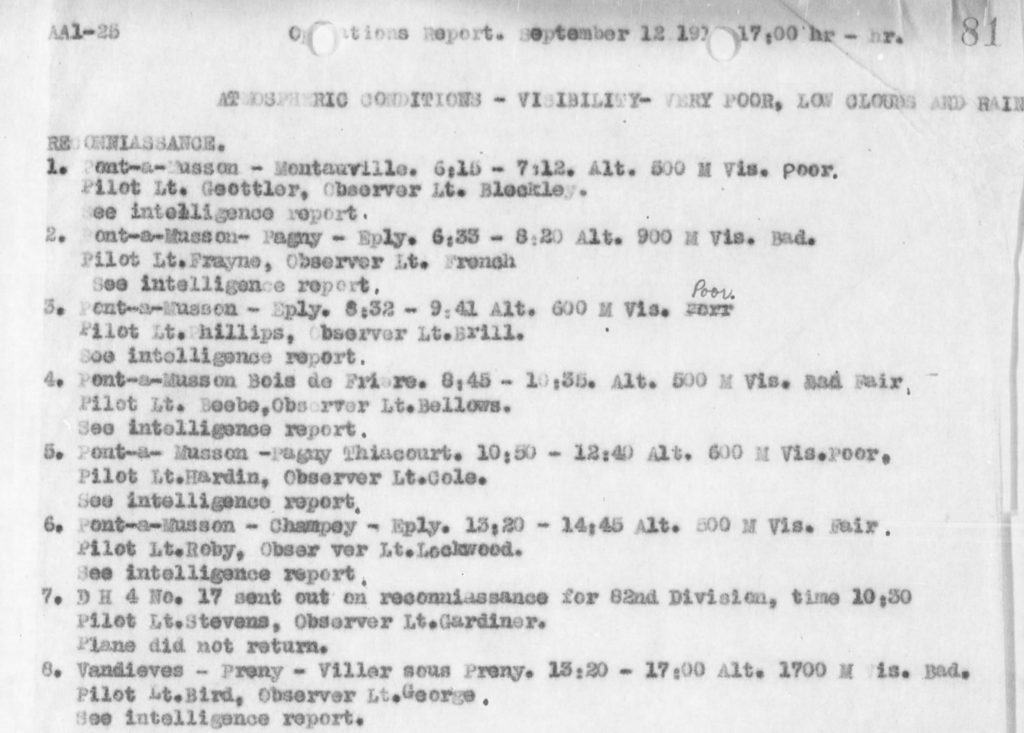

The combined effort of French and American forces to reduce the St. Mihiel salient began on September 12, 1918. The barrage against the German lines started around 2 a.m. Though twenty miles away, the noise kept the men at Bicqueley from sleep. “It had been raining hard for the previous twenty-four (or more) hours, but in the early morning it gave way to a heavy southwest wind (right into Germany) and low clouds.”23 Operations orders were for two planes from the 50th to set off about every two and a half hours starting at 5:30 a.m. until 3:30 p.m., with a final flight at 5:00 p.m., one plane to work with the 90th Division, one with the 82nd (in the event, the last two teams, at 3:30 p.m. and 5 p.m., did not fly, presumably because weather conditions had worsened.)24 Hardin and his observer Robert L. Cole were in the third pair, and scheduled for 10:30 a.m. They took off at 10:50 in the squadron’s plane No. 13 and were gone nearly two hours, flying at only about 600 meters in poor visibility; their course took them almost due north over Pont-à-Mousson to Pagny and then slightly southwest to Thiaucourt before they returned to the aerodrome.25 I have not found a copy of the intelligence report that they, like the other teams, filed on their return.

The next day, again in bad weather with poor visibility, Hardin, with Milton Keith Lockwood as his observer, set off at 12:30 p.m. on an infantry contact patrol. They flew even closer to the ground than on the preceding day, 500 meters, in the same general area as on the 12th, over Vieville (presumably Viéville-en-Haye), Norroy (presumably Norroy-lès-Pont-à-Mousson), and “River” (presumably the Moselle).26 It was noted that the “infantry did not show panels when called on”; this was a frequent problem for reconnaissance planes charged with locating troops and resulted apparently from inadequate preparation time and training—and the infantry presumably having more pressing concerns than signalling where they were. At the end of the day Lockwood wrote an account of the day’s flight in his diary:

. . . a call came in for someone to locate the line of the 90th Division at 11:00, so I was sent. I also was to locate a Boche battery west of Norroy. I took off all right, and flew over the lines for half an hour and fired my signals but the Infantry would not show up the line. Dropt my message at Division and Army Corps Hdqrs. And looked for Battery but could not find it. Norroy, however, is on fire and burning well. Didn’t see any Boche planes, or get shot at that we know of although I heard a machine gun twice when we were low over the lines. Very poor flying weather as the rain nearly draws blood but during this attack the planes must fly. The 90th Division took two days’ objectives in one day and are still going, and Allied shells are now falling in Metz. . . . The guns are shooting very heavily tonight. Today was Friday the thirteenth and I flew in Ship No. 13. That is breaking the hoodoo.27

The next day, September 14, 1918, Hardin set out around noon on another reconnaissance mission, this time with Adoph Oliver Dovre—who had reported only the previous day—as his observer.28 As the American divisions advanced north and then east, pushing the Germans back, reconnaissance also shifted east, and Hardin flew over Pont-à-Mousson, Eply, and Cheminot, the latter two on the right bank of the Moselle. For the first time, he was flying in good visibility, and at 1500 meters.29 However, for the first time also there was noticeable enemy aerial activity, and “Hardin suddenly found himself with five Huns after him.”30 Lockwood wrote in his diary the next day that “No. 13 came in last night, literally shot to pieces. Dovre’s first trip over and five Boche got on his tail. The wings and fuselage are riddled. One bullet thru the exhaust, one thru the pilot’s seat and another thru the observer’s rudder bar and also a handful of shrapnel in the plane, but they landed without a scratch. Dovre has never handled twin guns before and didn’t know how to work them. . . .”31

Hardin was among the pilots scheduled to make two reconnaissance patrols the next day, September 15, 1918—another day of good visibility—with Daniel Prather Brill as his observer. They flew over Pont-à-Mousson in the late afternoon at about 2500 meters and were able to provide an intelligence report; their other flight was aborted because of “wireless and motor trouble.”32 The St. Mihiel Offensive was by now essentially successfully concluded, but some reconnaissance continued. Hardin was assigned to fly on September 16, 1918, but motor trouble was again a problem. That afternoon Hardin and observer Howard C. French flew as far as Dieulouard, about four miles short of Pont-à-Mousson, before they had to make a forced landing.33 There were only two missions the next day and three on Sept. 18, 1918, in none of which Hardin was involved.

On September 19, 1918, Goettler recorded in his diary having gone into Toul and then, scouting for a ride back to camp, “found our French truck with Doc [Laurent Gustav Feinier], Hardin and Bird in it and on their way to Neufcha[teau] so [we] decided to go with them. Hardin was being taken to Hospital #18.” (American Base Hospital No. 18, operated by personnel from Johns Hopkins, was located at Bazoilles-sur-Meuse, just southwest of Neufchateau.) I find no information on Hardin’s injury or illness, but evidently he was sufficiently incapacitated that he did not fly again during the war. Morse, towards the end of his history of the 50th squadron provides a tally of missions and hours flown by each pilot and observer. His entry for Hardin gives him four missions and five hours thirty minutes total—perhaps Morse did not include the partial mission on the 16th.34 After the armistice, and after the squadron was relieved from duty with the First Army, Hardin replaced Bird as commander of C flight, which was now to go to “Army Candidate School, La Valbonne.”35

Hardin returned home on the S.S. America, sailing from Brest on March 28, 1919, and arriving at Boston on April 5, 1919.36 He settled in his hometown of Fort Smith, where he went into business with Henry Clay Armstrong, a fellow star athlete from the Fort Smith high school; they ran a tire and auto parts company under the name Hardin-Clay Co.37 Hardin also continued to play football, as noted from time to time by local newspapers.38

mrsmcq December 6, 2017; revised February 2020 to reflect Goettler diary.

Notes

(For complete bibliographic entries, please consult the list of works and web pages cited.)

1 Hardin’s place and date of birth are taken from Ancestry.com, U.S., World War I Draft Registration Cards, 1917–1918, record for Temple Paul Hardin. His place and date of death are taken from “Temple P. Hardin, Ex-Flier and Athlete, Succumbs.” I am grateful to Joe Wasson for a copy of this obituary and for information generally about Hardin. I am grateful to Steven A. Ruffin for the copy of the photo of Hardin reproduced here.

2 On Hardin’s parents, see documents available at Ancestry.com and the brief obituary for his father in “Deaths.”

3 See, for example, “Football Star to Italy.”

4 “To Aviation School.”

5 For a list of men in Hardin’s ground school class, see “Ground School Graduations [for August 25, 1917].”

6 Chalaire, “Thanksgiving Day with the Aviators Abroad.”

7 Foss, Papers, “Cadets of Italian Detachment Posted Dec 3rd”; Foss, Diary, entry for November 15, 1917, on the men already at Wyton.

8 See The National Archives (United Kingdom), Royal Air Force officers’ service records 1918–1919, record for Temple P. Hardin, on this and subsequent training postings for Hardin.

9 See the article on 99 at Barrass, “No 96 – 100 Squadron Histories.”

10 Cablegrams 650-S and 889-R.

11 Fell, “103 Squadron in the First World War,” indicates that 103 was equipped with DH.9s on March 19, 1918.

12 [Biddle?], “Special Orders No. 109”; the copy I consulted is dated June 5, 1918, but should almost certainly be dated July 5, 1918.

12a Benedict, “Special Orders No. 192.”

12b Goettler, diary entry for July 15, 1918.

12c Goettler, diary entry for July 16, 1918.

12d Harbord, “Special Order No. 148.”

13 Dates of assignment are provided by Sloan, Wings of Honor, pp. 325-26.

14 See Morse, The History of the 50th Aero Squadron, pp. 22-23, and Sloan, Wings of Honor, p. 316.

15 Morse, The History of the 50th Aero Squadron, p. 22. The 135th was the first.

16 Morse, The History of the 50th Aero Squadron, pp. 22-23.

17 According to Sloan, Wings of Honor, p. 316, only Bird, William David Frayne, and Henry LeNoble Stevens had flown DH.4s; Ruffin, “‘Dutch Girl’ over the Argonne,” p. 103, notes that Harold Ernest Goettler had considerable experience flying DH.4s and served as an instructor to pilots of the 50th Aero; see also Ruffin, “Mortal—Immortal,” p. 144, on DH-4s at Tours. See Jefford, Observers and Navigators, p. 120, on DH.4s at Stonehenge, as well as entries in Foss’s pilot’s flying log book that indicate he flew DH.4s while at Stonehenge (in Foss, Papers). It is now conventional to designate the English plane a “DH.4” and the American a “DH-4.”

18 Morse, The History of the 50th Aero Squadron, p. 23.

19 Ibid., p. 24.

19a Goettler, diary entry for September 4, 1918.

20 Morse, The History of the 50th Aero Squadron, p. 24. Sloan, Wings of Honor, p. 316, writes that “On the eve of battle 50th Sqdn moved to Dommartin-les-Toul, to be with the 1st and 12th Obs Sqdns in 1st C.O.G.”; see also Sloan’s reproduction of the order of battle for Sept. 12, 1918, on pp. 310-11. This move is not noted by Morse, and a “Resumé of changes of station of air service units which operated in the zone of advance” does not include this station for the 50th. Maurer, The U.S. Air Service in World War I, vol. 1, p. 237, indicates that the 50th was with the French 211th at Bicqueley, while the 1st and 12th were at an “airdrome just east of Toul.” Milton K. Lockwood, in his diary entry for September 12, 1918, states: “We are located at Bicqueley, south of Toul” (Ruffin, “‘The Luckiest Man in the Army’,” p. 167).

21 “50th Aero Squadron, Historical Account,” p. 59; Sloan, Wings of Honor, p. 320.

22 “50th Aero Squadron, Historical Account,” p. 63.

23 Morse, The History of the 50th Aero Squadron, p. 30.

24 See the operations order on p. 30 of Morse, The History of the 50th Aero Squadron, and compare to the operations report for September 12, 1918, on p. 81 of “50th Aero Squadron, Historical Account.”

25 See the operations report on p. 81 of “50th Aero Squadron, Historical Account.”

26 See the operations report for September 13, 1918, on p. 81 of “50th Aero Squadron, Historical Account.”

27 Ruffin’s transcription, p. 168 of Ruffin, “‘The Luckiest Man in the Army’.” I cannot account for the time discrepancy (12:30 vs. 11:00).

28 Morse, The History of the 50th Aero Squadron, p. 31.

29 See the operations report on p. 82 of “50th Aero Squadron, Historical Account.”

30 Morse, The History of the 50th Aero Squadron, p. 31. See Maurer, The U.S. Air Service in World War I, vol. 1, p. 240, on enemy air activity.

31 Ruffin’s transcription on p. 170 of Ruffin, “‘The Luckiest Man in the Army’.” See also Morse, The History of the 50th Aero Squadron, p. 31. No. 13 was evidently later repaired and reassigned to Walter Aitchison Thomson; see “50th Aero Squadron, Historical Account,” p. 91; see also the photo of Thomson with No. 13 on p. 169 of Ruffin, “‘The Luckiest Man in the Army’.”

32 “50th Aero Squadron, Historical Account,” p. 82.

33 “50th Aero Squadron, Historical Account,” p. 83.

34 Morse, The History of the 50th Aero Squadron, p. 83.

35 Ibid., p. 77.

36 War Department, Office of the Quartermaster General, Army Transport Service, Lists of Incoming Passengers, 1917 – 1938, Passenger list S.S. America.

37 See the entries for Hardin and Hardin-Armstrong in Calvert Directory Company, Fort Smith City Directory 1925–26. On Armstrong, see Martin, “Origin of Name ‘Marshal’ and Creation of Federal Court System,” pp. 13–14.

38 See, for example, “Razorbacks, Past and Present.”