(Troy, New York, July 2, 1894 – Royal Pines, North Carolina, August 12, 1964).1

Nial’s surname was originally spelled “Nihill”; his paternal grandfather changed it to Nial not long after coming to Troy, New York, from Ireland in the early 1850s.2 Nial’s father, Matthew T. Nial married Maria Hayes, apparently also of Irish descent, in 1891. The couple had two children, the older of whom, Agnes, died in 1914.3 Matthew T. Nial and some of his brothers followed their father, also Matthew Nial, into building trades and formed the successful Nial Brothers Construction Company in Troy.4

Thomas Matthew Nial attended school in Lansingburgh, the village in the northern part of Troy where his family lived. He graduated from Langsingburgh High School in 1913 and entered Syracuse University with the class of 1917. 5 A newspaper announcement indicates that he studied in the College of Forestry; a later article indicates he was in the College of Fine Arts and taking a special course in painting.6 Although Syracuse University yearbooks show him in attendance through 1917, it is not clear that Nial graduated with his year.7 When he registered for the draft on June 5, 1917, he was at Madison Barracks at Sackets Harbor and in the R.O.T.C. Not long after this, he transferred to the Aviation Section of the Signal Corps. It is of interest that others in his family were involved in aviation, and that his grandfather, Matthew Nial, patented an improbable-looking “flying machine” in 1907.8

Nial attended ground school at the University of Illinois with the class that graduated September 1, 1917. Most of the thirty men in this class, including Nial, chose or were chosen to go to Italy for flying training and were thus among the 150 men of the “Italian” or “second Oxford detachment” who boarded the Carmania at New York on September 18, 1917, to sail for Europe. After a brief stopover at Halifax the Carmania joined a convoy for the voyage across the Atlantic. The men sailed first class and enjoyed some leisure, including concerts featuring the violinist Albert Spalding, who was on board. They also had Italian lessons, conducted by Fiorello La Guardia, and, once they entered dangerous waters, they took turns at submarine watch. According to detachment member Fremont Cutler Foss, the last evening on board and the end of submarine watch were celebrated with a late night feast: “Last night about 11:30 the gang: Dietz, Forster, Deetjen, Neil [sic], Hagan, Fry and many others had a feast with food prepared for the guard which was called off at 9:30. Twenty loaves of bread and about twenty pounds of meat were ruined.”9

When the Carmania docked at Liverpool on October 2, 1917, the detachment members learned that they were not to go to Italy, but to remain in England for their training. They travelled by train to Oxford, where they spent the month of October repeating ground school at the Royal Flying Corps’s No. 2 School of Military Aeronautics. As much of their class work repeated material already covered in the U.S., the cadets (as they were now called) did not have to study hard, and they enjoyed exploring Oxford and the surrounding countryside.

Early in November 1917, twenty members of the detachment were selected to begin flying training at Stamford in southwest Lincolnshire, while the remaining men, including Nial, travelled farther north to Grantham to attend machine gun school at Harrowby Camp; they were in a holding pattern because there were not yet openings at training squadrons to accommodate them. At Harrowby Camp Nial initially shared a hut with Harvard DeHart Castle, Henry Bradley Frost, Edward Addison Griffiths, Lloyd Andrews Hamilton, Parr Hooper, Edward Russell Moore, and Melville Folsom Webber; Moore had been in Nial’s class at Illinois, while the others had attended ground school at M.I.T. and Ohio State University.10 A group of fifty men, including Frost, Hamilton, and Hooper, were able to set off for training squadrons on November 19, 1917, but Nial was among those who remained at Grantham through the end of November, which meant that he received about two weeks of training on the Vickers machine gun, followed by two on the Lewis, and also that he was at Grantham for the Thanksgiving celebrations orchestrated by the Americans at Harrowby Camp.

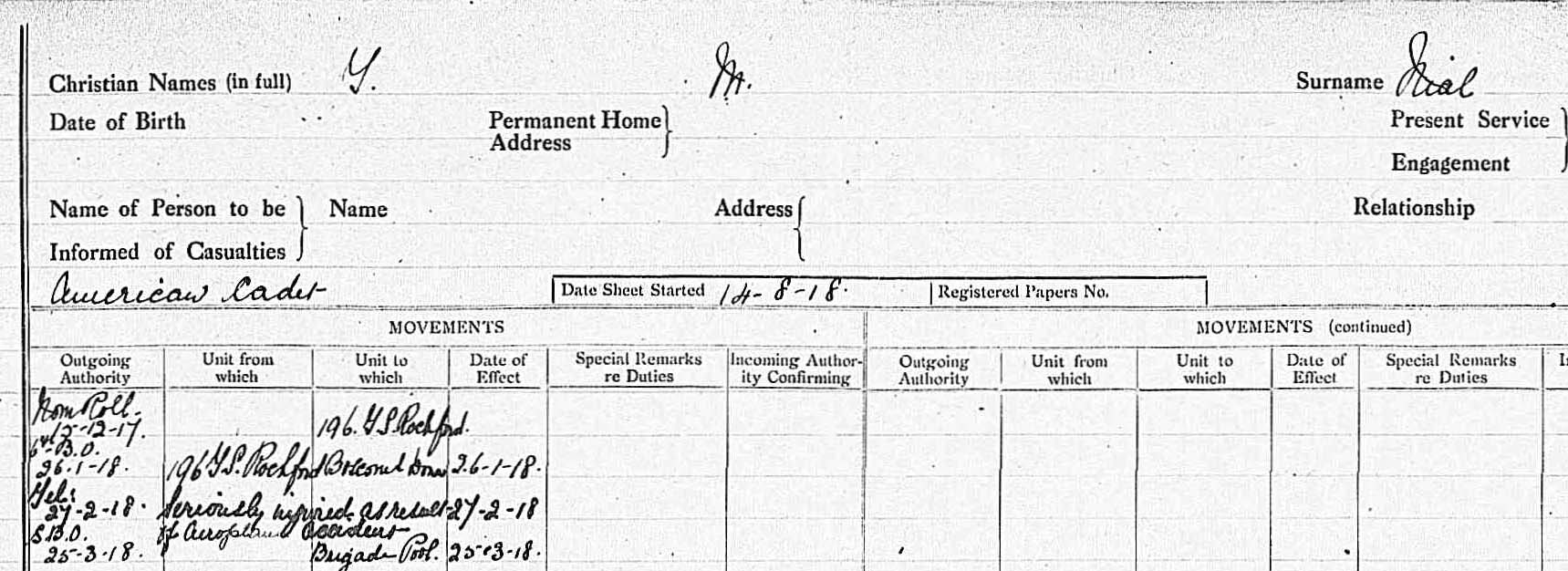

Finally, on December 3, 1917, the men still at Grantham were posted to flying schools. According to a list drawn up by Foss, Nial was one of twelve men posted to No. 61 Squadron, a home defense squadron in Rochford in Essex.11 Some, or perhaps all, of the men were quickly reassigned to No. 198 Night Training Squadron, which shared the airfield with No. 61 and which had Avros for training purposes.12 Nial’s R.A.F. service record indicates that in December 1917 he was at “196 T S Rochford,” but this is almost certainly a scribal error for “198 T S Rochford.” (No. 196 Training Squadron was at this time in Egypt.)

It is likely that Nial’s time at Rochford was similar to that of his fellow detachment member Uel Thomas McCurry, who in December wrote home that “I am having the time of my young life in spite of cold weather. Am billeted at the West Cliff hotel, Westcliff-on-Sea, near South End, Essex. I go to and from the aerodrome in a machine. Am flying every day. . . .”13

On January 26, 1918, Nial, along with McCurry and at least five of the other twelve detachment members at Rochford, was posted to Boscombe Down on Salisbury Plain in Wiltshire, presumably to No. 6 Training Depot Squadron.14 The posting indicates that these men had been selected for training as bomber and/or observation pilots. The planes available at 6 T.D.S. were (in addition to Avros) B.E.2c’s, B.E.2e’s, and DH6s—all two seaters designed or now used for training—and DH.4s, DH9s, and FK.8s, two-seater operational aircraft used for reconnaissance and bombing.15 Nial may already by this time, like McCurry, have passed the flying tests required to qualify for a commission as a first lieutenant—McCurry had done so while still at Rochford, and Nial’s experience may have been similar.16 In any case, their recommendations were among those that Pershing forwarded to Washington on February 16, 1918.17 A week after this, on February 23, 1918, Nial’s fellow second Oxford detachment member Jesse Frank Campbell noted in his diary that Nial and detachment member Kenneth MacLean Cunningham flew “A Ws”—presumably Armstrong Whitworth FK.8s—from Boscombe Down to where Campbell was stationed at London Colney.

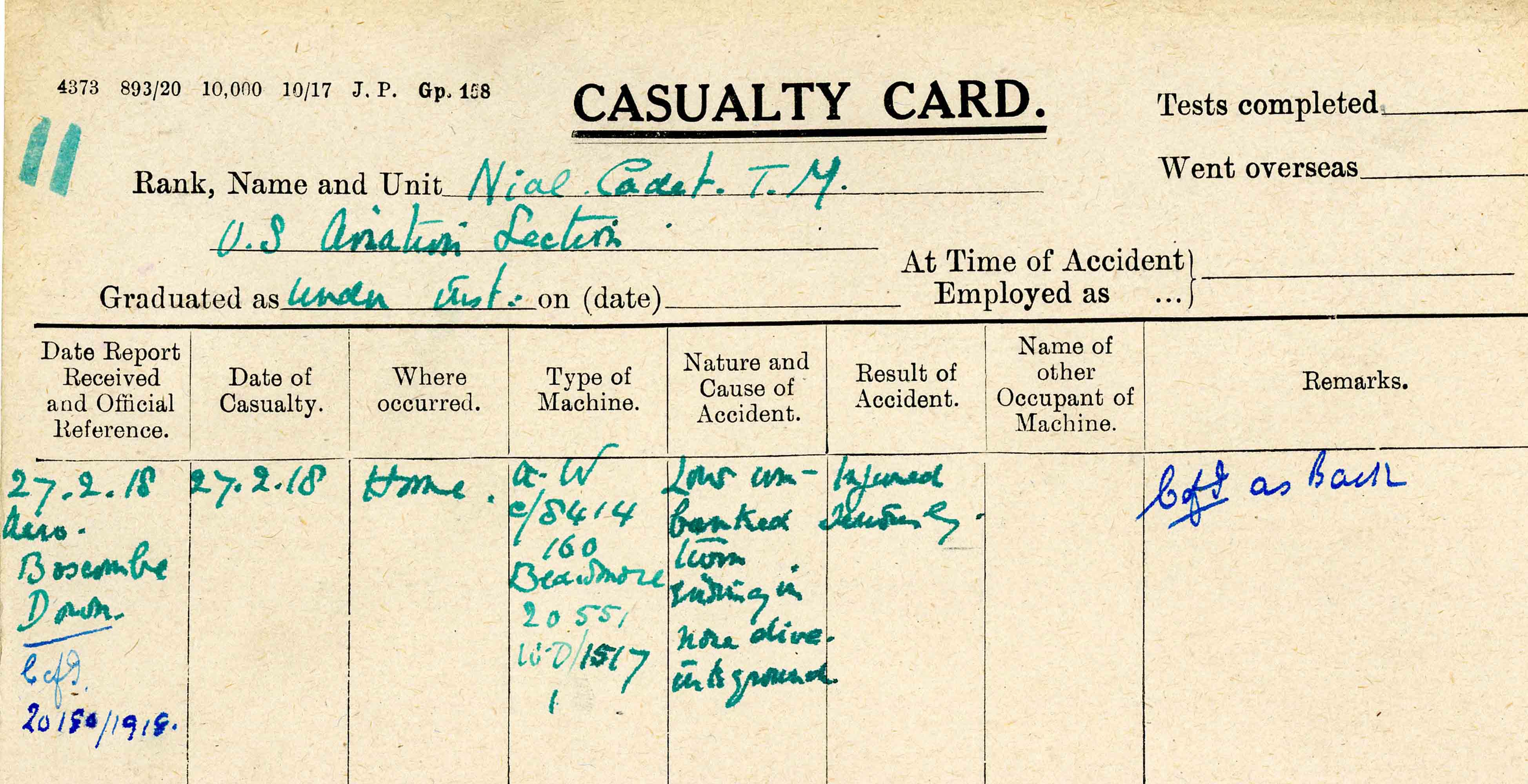

Four days later, on the morning of February 27, 1918, Nial, flying FK.8 C8414 at Boscombe Down, made a “low unbanked turn ending in nose dive into ground” and was “injured seriously”; he was not carrying a passenger.18

Cunningham apparently witnessed the accident and monitored subsequent events, visiting Nial every day in hospital and sending Nial’s parents an initial telegram, followed by a letter:

As Tom has not recovered enough to write you he asked me to do so for him. . . . His accident occurred Wednesday morning last. He had been up taking photos for about an hour and was just coming in. As ususal he was turning to make a landing, and when about sixty feet from the ground his machine went into a flat spin and he crashed to earth. When he was removed from the wreckage he was unconscious. He was taken to the tent hospital and fixed up to be taken to the main hospital and to the operating room. I waited to hear the outcome of the examination, and when they finished it was 1:30 p.m. The head Sister, twelve miles away, gave me a report, and it included three broken ribs, one of which slightly punctured a lung; a compound fracture of both legs and one knee badly smashed. . . . It was not until yesterday that he was able to recognize me. To-day he is much better, and although in great pain is very cheerful.19

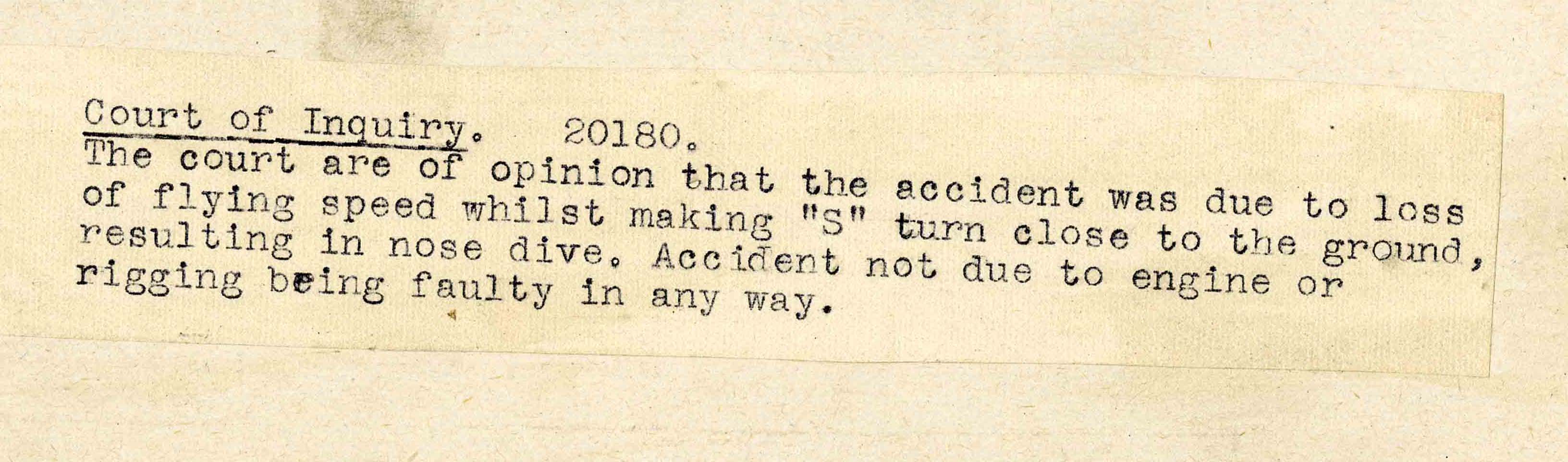

A week after the accident, Nial was well enough to write his parents with an account of the accident that seems to be a mixture of what he was told and what he remembered: “I find, they tell me, I had shut off the engine of a big A.W. and had started to land. I got into some very rough air and it threw me into a flat spin and then into a nose dive.” He continues: “I broke both legs, cut my face and smashed my chest in considerably, besides smashed the machine all to pieces. Outside of these facts everything was all right.”20

A court of inquiry concluded that the “accident was due to loss of flying speed whilst making ‘S’ turn close to the ground, resulting in nose dive.” There is no mention of “rough air,” but the statement goes on to assert that “Accident not due to engine or rigging being faulty in any way”— which seems rather ex cathedra, if the machine was, as Nial wrote, “all to pieces.” However, the inquiry also did not attach blame to the pilot.21

Given Nial’s injuries, it is not surprising that both he and Cunningham predict a long, slow recovery. I find no information on him between the time he wrote the above-cited letter from an otherwise unidentified “officers hospital” and his return to the U.S. in the early autumn. But it is possible he was able to spend part of his convalescence on the Isle of Wight courtesy of Bernard Francis Vernon Harcourt, the well-liked Major at No. 6 T.D.S. Moore, who had been with Nial at Illinois and in the same hut with him at Grantham, was also now at Boscombe Down. In a letter home dated March 13, 1918, Moore remarked that “One of our gang, who is just recovering from a rather serious crash, has an invitation to spend all the time he can at the Major’s summer home on the Isle of Wight.”22

Nial returned to the U.S. on the Melita, embarking at Liverpool on September 29, 1918, and arriving at New York on October 9, 1918.23 He spent at least part of the time after his arrival being treated at Walter Reed Hospital in Washington, D.C., and when he was honorabley discharged from service in April 1920 he was still 30% disabled.24 He learned, to his dismay, that, despite having been commissioned an officer and having been significantly disabled in the course of his service, he—having enlisted during the emergency created by the U.S.’s entry into WWI — was in a class not entitled to the same benefits as a person in a similar position in the regular army. He supported the legislation that was drafted to remove this anomaly, as evidenced by a letter he wrote to the New York Times in May of 1926.25 The legislation was finally passed over President Coolidge’s veto in 1928.26 It was perhaps this experience that had prompted Nial to take up a career in insurance and to write about compensation issues.27 He returned to active service in World War II.28

mrsmcq January 13, 2021

Notes

(For complete bibliographic entries, please consult the list of works and web pages cited.)

1 Nial’s place and date of birth are taken from Ancestry.com, U.S., World War I Draft Registration Cards, 1917–1918, record for Thomas M Nial. His place and date of death are taken from Ancestry.com, North Carolina, U.S., Death Certificates, 1909-1976, record for Thomas M Nial. The photo is a detail from a photo taken by Parr Hooper at Grantham; see the full photo further down the page.

2 “Ancestor: Matthew Nial/Nihill.”

3 Information on Nial’s family is taken from records available at Ancestry.com.

4 “Ancestor: Matthew Nial/Nihill.”

5 “Diplomas Presented”; Maxwell, compiler, The Catalogue of the Phi Delta Theta Fraternity, p. 516.

6 “Where They Will Go”; “To Sail for Italy.”

7 “To Sail for Italy”; The Onondagan 1920, p. 146, indicates Nial was in the class of 1918.

8 “Ancestor: Matthew Nial/Nihill.”

9 Foss, diary entry for October 2, 1917.

10 See Hooper, Somewhere in France, letter of [November] 4, 1917, and commentary.

11 Foss, Papers, “Cadets of Italian Detachment Posted Dec 3rd.”

12 The National Archives (United Kingdom), Royal Air Force officers’ service records 1918–1919, records for McCarthy, McCurry, Nial, and Young. On 198 T.S., see Stedman, “Night Fighter Pilot,” pp. 37 and 46.

13 McCurry’s letter is reproduced in “Air Training in England Exciting.”

14 See Nial’s above-cite R.A.F. service record.

15 On the aircraft at Boscombe Down, see Sturtivant, Hamlin, and Halley, Royal Air Force Flying Training and Support Units, p. 294.

16 On McCurry passing his flying tests, see “Learns to Fly in England.”

17 Cablegram 612-S; cablegram 852-R, dated March 1, 1918, confirmed the appointments.

18 See “Nial, T.M.”

19 “How Trojan was Hurt.”

20 Ibid.

21 The court of inquiry findings have been pasted to the back of the incident casualty card for Nial’s accident, “Nial, T.M.”

22 “Letters from Soldiers” (May 23, 1918).

23 See Ancestry.com, New York, Passenger Lists, 1820–1957, record for Thomas M Nial, as well as War Department, Office of the Quartermaster General, Army Transport Service, Lists of Incoming Passengers, 1917 – 1938, Passenger list of organizations and casuals on C.P.O.S. Melita.

24 See “Injured Flyer Home” and Ancestry.com, New York, Abstracts of World War I Military Service, 1917–1919, record for Thomas M Nial.

25 Nial, “Retired Emergency Officers.”

26 See President’s Commission on Veterans’ Pensions, Compensation for Service-connected Disabilities, p. 41.

27 See, for example, Michelbacher and Nial, Workmen’s Compensation Insurance.

28 “Name Major Nial Commander of Syracuse Army Air Base.”