(Chicago, April 30, 1894–Naperville, Illinois, May 1982).1

Training in England ✯ France ✯ 11th Aero, St. Mihiel ✯ Meuse-Argonne

Like many of his fellow second Oxford detachment members, Walter Andrew Stahl was of German ancestry.2 His maternal grandfather was born in Hanover, his maternal grandmother in Oldenburg. They apparently emigrated separately to Wisconsin, where they married in 1860. Stahl’s mother, Augusta Redeker, was born in Two Rivers, Wisconsin. Stahl’s paternal grandparents were born in Mecklenburg and also emigrated to Wisconsin. His father, Charles John Stahl, was born in Manitowoc, Wisconsin, but moved as a young man to Chicago, where he worked as an “expressman,” i.e., he was involved in express (package and mail) delivery service. He returned briefly to Wisconsin to marry Augusta Redeker in Two Rivers in 1888, but lived with his family for the rest of his life in Chicago, where he went into the grocery business. There were three children, two girls, and, in the middle, Walter Andrew Stahl, who is recorded as having been christened Walter Heinrich Andreas Stahl.3 At some point he acquired the nickname Jake, and the informal history of the 11th Aero, with which he served, mentions “‘Jake’ Stahl, known only to his parents as Walter.”4

Stahl went to high school at Lane Tech College Prep in Chicago and then entered the University of Illinois at Champaign, where he majored in mechanical engineering.5 While in college he was active in the Tau Kappa Epsilon fraternity.6 His draft card describes him as tall, so it is not surprising that he chose basketball as his college sport.7 After graduating in 1916, he worked at the Buda Engine Company in Harvey, Illinois. He served in the Officers Reserve Corps, initially at the University of Illinois, and then, in the spring of 1917, in the training camp at Fort Sheridan.8 He applied to and, apparently after correction of a problem with his eyes, was accepted by the Aviation Section of the Signal Corps.9 He returned to Champaign and the University of Illinois for ground school at Illinois’s School of Military Aeronautics, graduating on September 1, 1917.10

There was much speculation about where graduates from this ground school class would go for actual flying training, with information and plans changing frequently. The initial understanding, according Vincent Paul Oatis, one of Stahl’s classmates, was that the men would “go to Rantoul [Illinois] to the aviation field and pursue the actual flying game from three to four months.”11 However, in mid-August 1917, again according to Oatis, there was a request for volunteers “who would like to go to Italy for their air training. Right now Italy is about the best in the world in flying, so I grabbed at it and applied. Nearly everyone in our squadron did likewise.”12 After some further confusion as to whether some of those who had signed up might go to France instead, all but five of the approximately thirty men in this Illinois S.M.A. class, including Stahl, became part of the detachment that set out from New York on September 18, 1917, on the Carmania, bound for Europe on the understanding that they, the 150 cadets of the “Italian detachment,” would learn to fly in Italy.

After a brief stopover at Halifax the Carmania joined a convoy for the voyage across the Atlantic. The men sailed first class and enjoyed some leisure, including concerts featuring the violinist Albert Spalding, who was on board. They also had Italian lessons, conducted by Fiorello La Guardia, and, once they entered dangerous waters, they took turns at submarine watch. When the Carmania docked at Liverpool on October 2, 1917, the detachment members learned that they would not continue on to Italy, but instead remain in England for their training and to attend ground school (again) at the Royal Flying Corps’s No. 2 School of Military Aeronautics at Oxford University.

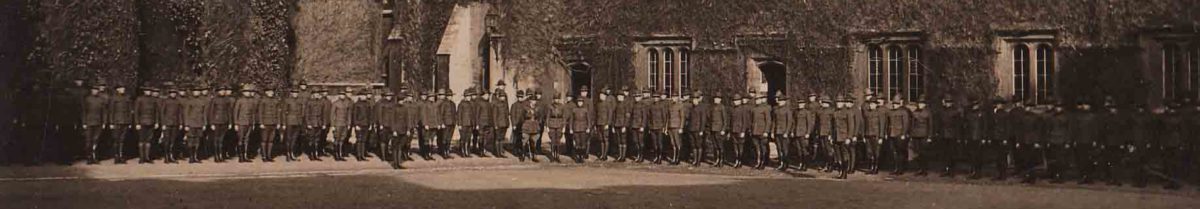

On arrival at Oxford the 150 cadets were divided into two groups, with sixty of them assigned rooms at The Queen’s College and ninety at Christ Church College; if I have correctly identified Stahl in a photo of cadets at Christ Church, it was to this college that he was assigned. At some point the “Italian detachment” came to be called the “second Oxford detachment”— there was another group of American aviation cadets who had arrived at Oxford in early September.

Although initially dismayed at having to do another round of ground school, the men of the detachment made their peace with the situation and in retrospect recognized the benefits of R.F.C. training. Their British instructors, unlike those in the U.S., had had war flying experience, and this added considerable interest to the course work. Since the men had already covered much of the material, they did not have to study especially hard, and they enjoyed Oxford hospitality and explored the town and surrounding countryside. There were also sports, including boxing, and Stahl was “a heavyweight member of the [American] team against the English cadets.”13

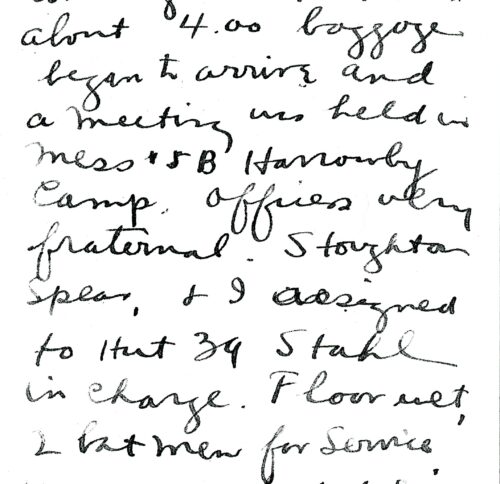

Towards the end of October, it was learned that twenty of the men of the second Oxford detachment would go straight from Oxford to a flying school, but the shortage of places at training squadrons meant that the others, including Stahl, were assigned to a machine gunnery school at Camp Harrowby near Grantham in Lincolnshire. On November 3, 1917, they set out from Oxford by train, arriving at Grantham after a six-hour journey.

In his diary for this day Fremont Cutler Foss notes that he, along with Perley Melbourne Stoughton and George Dana Spear, were “assigned to Hut 39 Stahl in charge.” The men spent two weeks learning about and practicing with the Vickers machine gun. Just as they were finishing and facing the prospect of the next two weeks on the Lewis gun, they learned that fifty places had opened up at various R.F.C. squadrons, and Stahl was among those selected to fill them. Along with nine others (Adolf Drey, William Wyman Mathews, George Orrin Middleditch, Oatis, Chester Albert Pudrith, Joseph Hiserodt Sharpe, Ervin David Shaw, Fred Trufant Shoemaker, and Lynn Lemuel Stratton), he was assigned to Waddington, about twenty miles north of Grantham and just south of Lincoln. At some point, possibly from the start of his time at Waddington, Stahl was assigned to No. 48 Training Squadron.14 His training there presumably resembled that of the much-better documented Oatis.

During the first two weeks at Waddington Oatis did not do any flying—perhaps because he and his fellow cadets were being given yet more ground instruction, or perhaps because of poor weather or a lack of planes. Then in a letter begun on December 11, 1917, Oatis wrote that “Last Tuesday we started flying and most of us are already soloing.” Oatis’s log book shows that on December 4, 1917, he flew in a DH.6, a dual control two-seater plane designed for training and one associated with preparing pilots for bombing or reconnaissance, rather than for scout (fighter) planes. Oatis went up solo in a DH.6 on December 10, 1917, and by February 12, 1918, had accumulated very nearly twenty hours solo flying. This is significant, because twenty hours solo was apparently a prerequisite for being recommended for a commission; it appears that Middleditch and Pudrith, and perhaps also Stahl, had reached this goal as early as January 15, 1918.15 In any case, the names of these three men were forwarded to Washington in a cablegram from Pershing dated February 11, 1918, with the recommendation that they be commissioned.16 The confirming telegram (which also confirmed the appointment of John Warren Leach) was dated February 20, 1918.17 Stahl was thus among the first members of the second Oxford detachment to receive a commission as a first lieutenant.18 His continued swift progress is apparent from the fact that he graduated in the R.F.C. on March 11, 1918.19 Having done so would have entailed passing a number of tests, including making a cross-country flight, flying at high altitude, and successfully flying a service plane. Two days previously, and presumably in anticipation of his graduation, he had been transferred from No. 48 T.S. at Waddington to No. 44 T.S., also at Waddington.20 This meant he would now be able to train on service machines such as the DH.4 and DH.9, two-seater planes designed for reconnaissance and bombing.21 At some point during his time at Waddington, Stahl was put “in command of flying officers and cadets at the station”—he evidently had notable leadership qualities.22 A post -war account states that he “was placed in command of some 40 American cadets when friction arose between the flying officers and a non-flying lieutenant in charge of the American mechanics.”23

Waddington, inevitably, like other training stations, had its share of plane crashes and fatalities. Of the men who had come to Waddington from Grantham with Stahl, Sharpe was killed in early January 1918, and Middleditch on March 12. Pudrith, in the plane with Middleditch when it crashed, survived, for a while, and Stahl was, according to William Ludwig Deetjen, among those who went into Lincoln a few days after the accident to visit Pudrith in hospital.24

Deetjen mentions Stahl again a few days later, writing about going to Nottingham and dining out and going to shows with him and James Mitchell Coburn.25 A month later Stahl was in London, presumably on leave from Waddington, and dining at the Strand Palace with Joseph Kirkbride Milnor and Guy Samuel King Wheeler.26

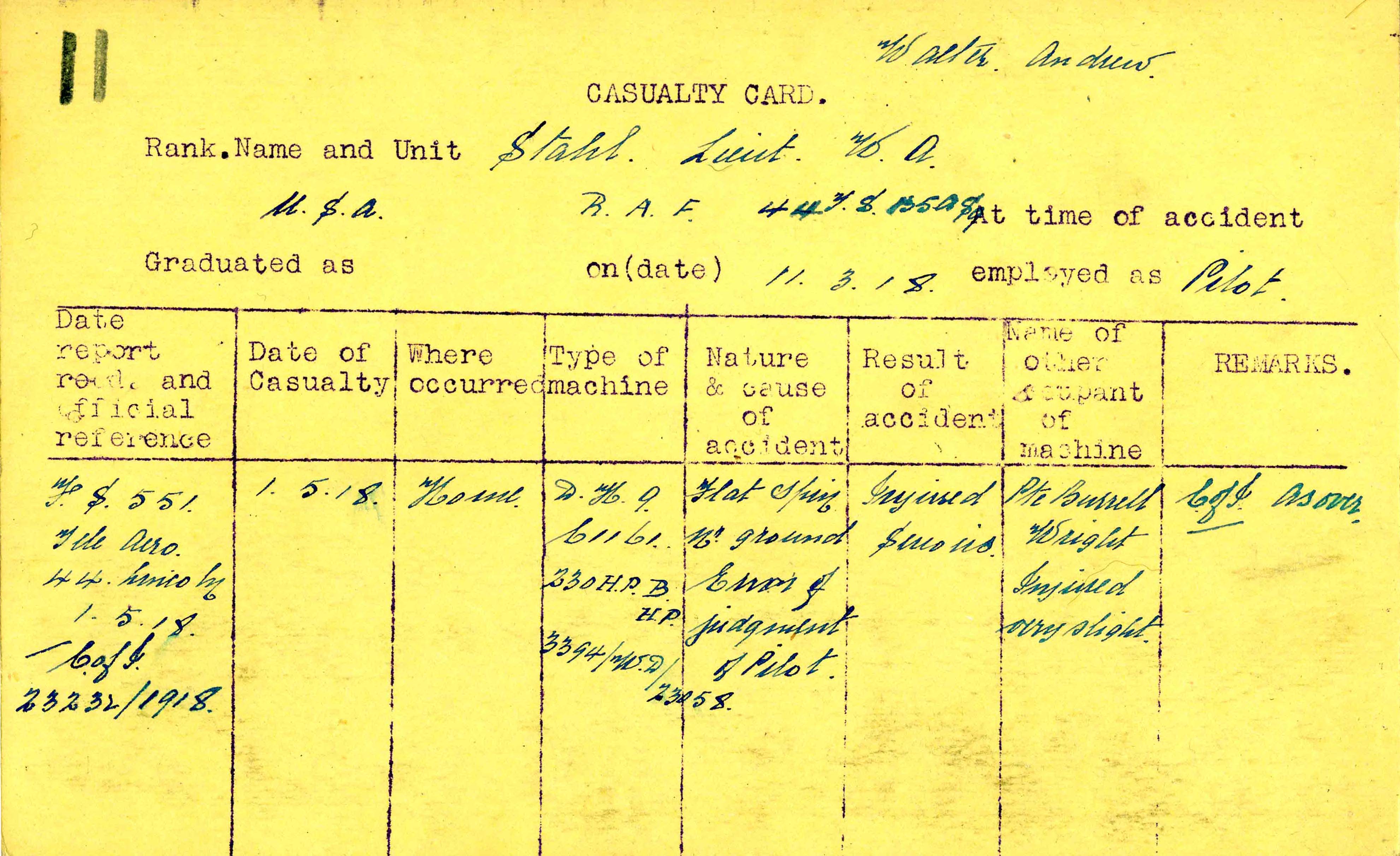

A week later, on May 1, 1918, Stahl was injured in a crash at No. 44 T.S. at Waddington. He was flying DH.9 C1161 with Burrill Everett Wright in the observer’s seat.27 Sixteen-year-old Wright, a private in a group of men from the U.S. 135th Aero that had been sent to Waddington for training, was also, slightly, injured. Stahl had, according to the description provided in a court of inquiry summary, on a second attempt to land, turned to avoid a plane in front of him without banking sufficiently, and his plane went into a spin and crashed.

According to Stahl’s own account, “It was a windy day. I went into a flat spin about 100 feet up. A crash seemed certain but I worked at the controls until the last instant, then covered my face to keep from ‘eating the compass.’ The force of the crash tore the leather sleeves from my jacket but my arms saved my face. My hip was dislocated, however, and I was wedged so tightly in the wreckage I had to be chopped loose.”28 Oatis took over Stahl’s duties at Waddington for the next three weeks.29

At least by mid-June of 1918, Stahl was back in the air: the entry in Foss’s pilot’s flying log book for June 14, 1918, records practicing aerial fighting at Waddington in a DH.9 with Stahl, who was perhaps also in a DH.9. From Waddington Stahl went to the No. 2 School of Aerial Fighting at Marske-by-the-Sea.30

By early July Stahl had evidently completed his training, and his name appears on a long list of men ordered from London to the American 3rd Aviation Instruction Center at Issoudun in the Loire region of central France.31 From there he was sent, presumably at the same time as Oatis, to the 7th A.I.C., the bombardment training school at Clermont-Ferrand, about ninety miles southeast of Issoudun.32 Assuming again that Stahl’s training resembled that of Oatis, he would have spent the latter half of July and much of August flying French Breguets—whether he was as disappointed as Oatis at flying these planes rather than DH-4s (the American version of the British DH.4) is not known. However, at least near the end of their time at the 7th A.I.C., DH-4s had become available. Oatis recorded in his pilot’s flying log book on August 30, 1918, that he went up briefly in a “Liberty” DH-4 with Stahl as his passenger.

The next day, Oatis, and presumably also Stahl, finished at Clermont-Ferrand. Oatis, writing home on September 12, 1918, indicates that “after waiting a couple of days for orders [I] was sent to a point near Paris”—this was probably Orly, as suggested by an account of Stahl’s wartime work.33 Oatis goes on to write that he—and presumably also Stahl—“received further orders, that sent me up where things happen”—this was almost certainly Amanty; a number of sources note an influx of pilots and observers to Amanty from Clermont-Ferrand on September 9, 1918.34 An excited postscript to Oatis’s letter of September 12, 1918, indicates he was that day assigned to a squadron, and this is the date of his and Stahl’s (and Robert Brewster Porter’s and Shoemaker’s) assignment to the 11th Aero as recorded in the squadron’s roster.35

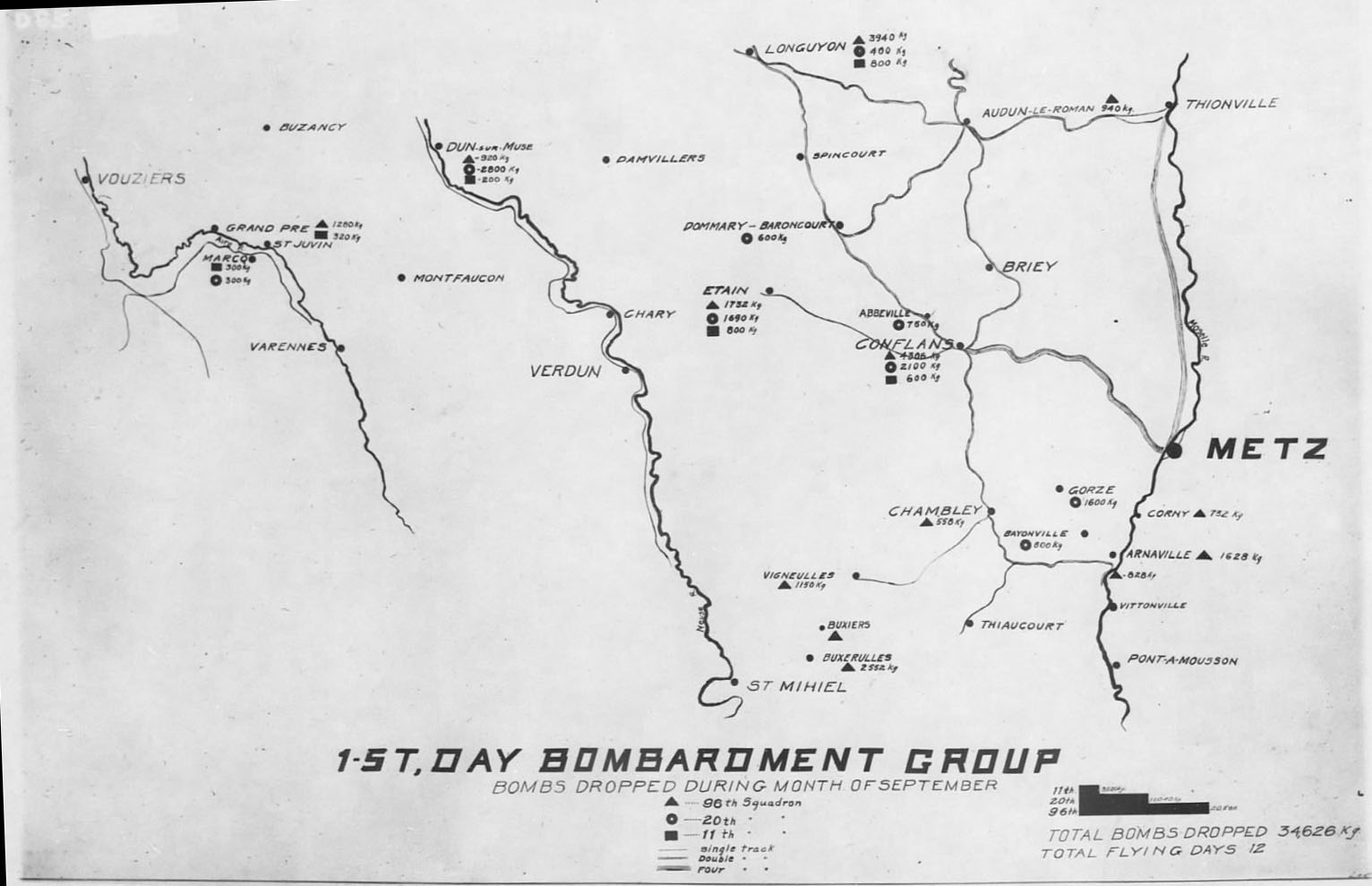

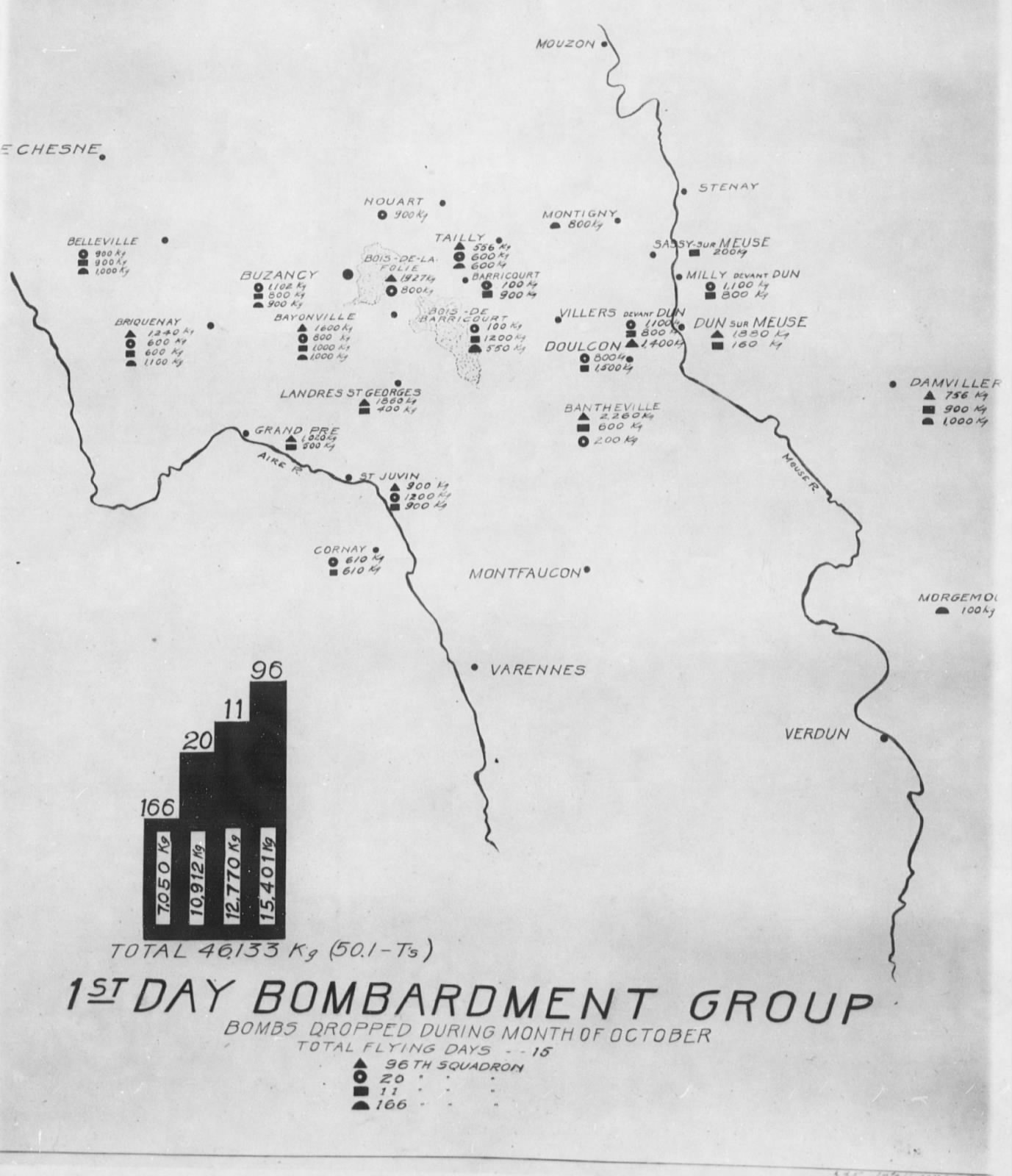

The field at Amanty, about twenty-five miles south of St. Mihiel and the front, was shared by the 11th, the 20th, and the 96th Aero Squadrons, the last-named being the only operational American bombing squadron up to this point. Although instructions for daylight bombing were drawn up in the course of August, it was only on September 10, 1918, that the three squadrons became the First Day Bombardment Group.36

By this time the newly-established American First Army was completing preparations for the St. Mihiel Offensive, in which the First Army, with assistance from the Allies, would seek to wipe out the German held salient that jutted southwest from the Allied line to encompass the town of St. Mihiel on the east bank of the Meuse. It had been hoped that the attack could begin before the autumn rains, but it was delayed from the 7th until the 12th, and, in any case, the rains came early.37 The weather just preceding and during the Offensive was terrible and precluded practice flights. John Cowperthwaite Tyler, of the 11th Aero, noted in his diary on September 10, 1918, “New bunch anxious to fly, but no chance.”

On the first two days of the St. Mihiel Offensive, September 12 and 13, 1918, some of the pilots of the 11th (and 20th) Aero, whose planes were not yet outfitted for bombing, were tasked with escort duties, while four were required for “a detail of four command airplanes to take station at Maulan, beginning at 7:00 A.M., September 12.”38 Stahl was evidently among these four; they learned that they were to do contact patrol work, i.e., determine the location of advancing American ground troops.39 Stahl later recalled that “Our hearts were in our boots. . . . It meant flying low over the lines on the St. Mihiel salient, exposed both to anti-aircraft fire and German planes.”40 On the 12th, two pilots from the 20th Aero, Merian Coldwell Cooper and George Marter Crawford flew missions with their respective observers (Edmond C. Leonard, 20th Aero, and James O’Toole of the 96th); Crawford and O’Toole did not return.41 Stahl indicates that only three of the four required DH-4s arrived at Maulan, so that it may have been only himself and his observer who went out the next day. He recalled that “we flew only a few hundred feet off the ground as the Yankees advanced beneath us.”42 The unofficial squadron history credits Stahl with having “earned the first distinction for the squadron by a very successful contact patrol just a few hundred feet over the heads of the American infantry at Vignuelles [sic.]”43

There is no mention of Stahl’s mission in official histories and no record of the name of his observer. However, there is a “report from reconnaissance mission sent out from Maulan” the morning of September 13, 1918, in which it was noted that “Vigneulles is burning” and that “No American troops [were] seen in Vigneulles”; the plane “Flew over woods southeast of Vignuelles [sic] at altitude of 100 to 200 meters.” The report names the crew as “Lieut. Correl, Pilot and Lieut. Stohl, observer.”44 I suspect that the names and roles have been garbled, and that this was pilot Stahl and his observer Ralph Ivan Coryell of the 96th Aero. That Coryell had been recommended for duty at Maulan is apparent from the entry for September 11, 1918, in the diary of Howard Grant Rath, who was an observer in the 96th and who also served as operations officer and historian for the First Day Bombardment Group.45

Stahl returned to Amanty. Although official records do not show this, it is almost certain that Stahl took part in the 11th Aero’s first mission on the morning of September 14, 1918, when they, along with flights from the 96th and the 20th bombed the railway yards at Conflans-en-Jarnisy. In a letter written shortly after the Armistice, Hasell Davies Archer, whom Stahl may have worked with at Clermont-Ferrand and who would serve as Stahl’s observer on all his documented missions, mentions “the first raid I made” when he saw “two of our formation go down in flames.”46 Archer is here presumably referring to the planes flown by Shoemaker and by Horace Greeley Shidler, which were shot down south of Rezonville at about 8:00 a.m. on September 14, 1918, as they started for home.

According to Robert Newell Groner, Jr., Shoemaker’s observer, ten machines started out on this raid, but three turned back before crossing the lines at Verdun; the squadron’s unofficial history also mentions that it was seven planes that were attacked after dropping their bombs.47 Possibly these numbers are incorrect. The 11th Aero’s raid report for this mission indicates that the men on this mission who deserved credit for downing an enemy plane during the encounter with the enemy were flight leader Roger Fiske Chapin , deputy leader Tyler, Lester S. Harter, Reuben Dallam Biggs, and Ector Orr Munn and their respective observers; they, along with Shoemaker and Shidler would be the seven documented as having reached the objective.48 However, Oatis also, according to both his log book and his account of this raid in a letter home, reached the objective.49 And Archer wrote that he “had seen two of our formation go down in flames,” which suggests that he and, presumably, Stahl were present during the aerial fighting that took place as the flight made its way back to the lines from Conflans.

Records show Stahl and Archer flew again the next afternoon (September 15, 1918).49a The objective was Longuyon, a good sixty-one miles north of Amanty. The two formations—one from the 96th Aero and one from the 11th— that made up this mission set out at shortly after 3:00 p.m. and returned just under two hours later. According to Norris’s narrative history, “All teams reached the objective and bombed at a height of 14,000 feet.”50

It appears that the next day Stahl and Archer flew the first and third of that day’s missions, each of which involved flights from all three squadrons.50a Longuyon was again the target on the first mission, which set out soon after 6:00 a.m.; in the late afternoon, the objective was once again Conflans-en-Jarnisy.51 Records indicate that some of the teams listed did not actually take off, and of those that did, not all reached the objective, but further details are lacking. It is notable that on the first mission, Stahl, in plane 358 with Archer, was, judging by where he appears in the listing, serving as deputy flight leader.52

The First Day Bombardment Group as a whole was not ordered out on the 17th. Rath noted in his diary that “The weather was worse than ever today. . . . We wait for orders but thank the Lord none come in. The Americans seem to have taken all they want at present—the St. Mihiel ‘hernia’ has been completely wiped out.”53 Nevertheless, planes from the 11th Aero “left field on bombing mission with Conflans as the objective, at 11:05 o’clock. Our planes were used as protection planes on this mission. . . . All machines returned safely at 12:45 o’clock.”54 Neither the squadron’s narrative history nor its raid report specify how many planes took part in this mission, much less who the crews were, so that it is not known whether Stahl flew this day.

The next day, September 18, 1918, the weather was even more inclement. Nevertheless, late in the day, ten planes from the 11th Aero were ordered out on a bombing mission; four returned prematurely, and five, including that piloted by the squadron’s commanding officer, did not return at all. Only Oatis and his observer completed the mission and returned safely. It had been assumed that the weather would preclude flying missions on this day, and a number of pilots who might have flown were sent instead to Colombey-les-Belles to bring back new planes: this may account for Stahl’s not having been assigned to the raid.55

During the few days that it had been active, the 11th Aero had lost fourteen men: the two teams that did not return on September 14, 191, and the five teams that failed to return on September 18, 1918.56 The unofficial history of the squadron describes the squadron at this point as extremely discouraged and as having lost confidence in officers higher up the chain of command.57

No missions were flown by the First Day Bombardment Group from September 19 through September 25, 1918. On September 24, 1918, the three squadrons began moving—unobtrusively, so as not to alert the enemy—from Amanty to Maulan, twenty miles to the northwest, as part of the extension of the American First Army’s front from the St. Mihiel sector to the Argonne Forest; the squadrons were joined at Maulan by the not-yet-operational 166th Aero.

Shortly before the move, new pilots were assigned to the 11th, including Dana Edmund Coates, Ralf Andrews Crookston, Charles Louis Heater, and George Dana Spear from the second Oxford detachment and Alfred Clapp Cooper of the first Oxford detachment. Uel Thomas McCurry, second Oxford detachment, would arrive soon after the move to Maulan. Of these men, only McCurry and Heater had had operational experience.58 Heater’s, flying DH.4s with No. 55 Squadron R.A.F., was extensive and warranted his being appointed the 11th Aero’s new commanding officer. Between Heater’s skilled leadership and the recognition by higher ups that changes needed to be made, the 11th was able to come back from the brink. In a very short period, Heater taught his pilots close formation flying, and the 1st Day Bombardment Group would soon start using larger and thus better protected formations.59

The Meuse-Argonne Offensive opened in the very early hours of September 26, 1918. The role of the 1st Day Bombardment Group was to disrupt the movement of German troops and supplies by bombing “Troop Concentrations and Convoys,” and “Dumps, Railheads, Camps & Command Posts.”60 They were originally tasked, unrealistically, with targeting sites as far behind the lines as Carignan and Lumes.61 In practice, they were initially able to reach and bomb locations on and near an arc running approximately from Grandpré to Dun-sur-Meuse to Etain, all roughly fifty miles north of Maulan.62

On the morning of September 26, 1918, the First Day Bombardment Group bombed Dun-sur-Meuse; the 20th Aero suffered losses that recalled those of the 11th from earlier in the month. Nearly all of the planes of the 11th Aero had to return before crossing the lines. A memorandum suggests that Stahl was tapped to lead this mission. In the event he did not take part in it—standby memoranda listings frequently differ from the lists recording who actually flew.63

In the afternoon the 11th, followed by the 20th, targeted Etain, a few miles over the lines east of Verdun. Seven of eight teams from the 11th, led by Cyrus John Gatton, and including Stahl and Archer, reached an altitude of 13,000 feet in good weather, encountered no enemy aircraft, and dropped bombs on the town.64 The unofficial squadron history recalled that “This was the first successful raid we had made in comparative safety and everyone could notice the improved morale resulting from it.”65

The next day, September 27, 1918, the First Day Bombardment Group squadrons, perhaps as much out of necessity as by design, flew in a single large formation for the first time. The 96th Aero had lost many pilots and observers, but was well supplied with Breguet 14 B.2 planes. For that day’s single mission, the 11th and the 20th each loaned pilots and observers to supplement the few available teams from the 96th.66 Pilots from the 11th included Stahl, Oatis and Porter; none of them had previously flown Breguets operationally, although Oatis, certainly, and probably Stahl and Porter as well, knew them from Clermont-Ferrand. According to Rath, the squadrons “Stood on alert all day—but rain & clouds. Just at 4:45 p.m. when everything was called off, H.Q. orders a raid out. Major says can’t be done but we have to put one on any way.”67 11th Aero records indicate that the objective was once again Dun-sur-Meuse, fifty miles due north of Maulan.68 Nearly half of the approximately twenty Breguets had to turn back before crossing the lines; the twelve that continued on diverted to the much nearer Etain, dropped their bombs, and returned home safely without being able to observe results due to cloud cover. The records available to me do not indicate which pilots reached the objective.

The next day planes from the 11th set out for Bantheville, but bad weather forced them to return; as there is no list of participants, it is unknown whether Stahl flew this mission. He and his observer Archer are listed among the teams that took part in a mission to bomb Grandpré and Marcq late in the afternoon of September 29, 1918. There were two formations: one of Breguets flown by teams from the 96th and 11th, and one of DH-4s from the 11th and 20th. Stahl and Archer flew in the second formation and were apparently among the teams that, unable to keep up with their formation, had to return before reaching Marcq.69

High wind kept planes on the ground on the last day of September.70 Stocktaking at the end of the month showed an impressive number of missions undertaken by the squadrons of the First Day Bombardment Group, but also a distressing number of casualties—thirty-eight men “missing,” distributed fairly evenly among the three operational squadrons.71

On the first of October another mission like that of September 29th was made, with a formation of Breguets followed by a formation of DH-4s from the 11th and 20th. Unfortunately the configuration of the second formation, which included Stahl and Archer, was unwieldy, and that and the fact that flight leader Oatis’s observer lost his helmet and goggles at high altitude forced nearly the entire formation to abandon the mission and straggle home without crossing the lines.72 Oatis described this mission in a long letter home a few days later, and then went on to write at some length about tight formation flying. He noted of one particular pilot-observer team that “When you have fellows like that flying next to you, about half your worries are removed, as you know they will be right there in a pinch, and you [sic] will never lose their heads and smash into you when you are not watching them. That is the sort of pilot old Jake Stahl is. He can come almost close enough to shake hands with me and I never worry the least bit.”73

Another combined mission was flown the next morning, but with a workable configuration for the DH-4s of the 20th and 11th Aero Squadrons. It appears that Stahl and Archer were among the teams that succeeded in reaching and bombing St. Juvin on this, their eighth (documented) mission.

The 11th Aero flew a number of missions during the period October 3–6, 1918; Stahl is not recorded as having taken part in them; weather precluded flying on the next two days. On October 9, 1918, teams from the 20th and 11th, flying separate formations, targeted St. Juvin and Bantheville. On this raid, according to the unofficial squadron history, “Jake Stahl gave everyone a bad scare by crossing the lines with a bad motor, which forced him out of the formation. He managed to reach the objective and return to our own side of the lines but was finally forced down at Courcelles. It was several hours before we could learn what had befallen him.”74 According to Stahl’s own, account, he did not actually reach the objective:

Our squadron started over the lines to bomb a German depot. I had a bad machine and had been forced back twice before but I’d sworn to make the flight this time. The motor sputtered, and I crossed the lines 1,500 feet below the formation. I finally saw I couldn’t make the objective so signalled to Archer, my observer, to drop the bombs and we turned back, losing altitude all the while. I spotted a flying field just behind the lines and made for it. But I was unfamiliar with it and overshot the field. The plane just cleared a fence at the end.75

Stahl goes on to recount how, when French officers came to investigate, he and Archer were nonchalantly eating flapjacks with some American soldiers detailed to guard an ammunition dump.

Stahl was not among the pilots on the two large multi-squadron missions flown on October 10, 1918; he was perhaps overseeing the repair of his plane. In passing I note that these were the last missions that involved the 11th and 20th squadrons loaning pilots to the 96th to fly their Breguets. A period of bad weather followed, and the squadrons of the First Day Bombardment Group enjoyed a rainy week during which no missions were flown.76

When, on October 18, 1918, they resumed flying, they undertook a mission that is notable for its size: flights from the 11th, 20th, and 96th were joined for the first time by a flight of DH-4s from the 166th Aero. Sixteen planes from the 11th took part in this mission; Stahl, who was apparently deputy flight leader, was not among the eleven pilots who reached and bombed Bayonville.77

Weather again precluded flying until October 23, 1918. On that day: “Opposed by vicious E.A. attacks and unusually active and accurate anti-aircraft fire, two missions against Buzancy, Bois de Barricourt and Bois de la Folie were successfully carried out, the 20th and 11th making the first and all four squadrons joining in the second.”78 The morning mission comprised a flight of twelve planes from the 20th Aero and a flight of thirteen, including Stahl’s, from the 11th. The 20th Aero took off at 8:35 a.m., with the 11th following ten minutes later. The 20th dropped their bombs on Buzancy at 9:50, and the 11th, including Stahl, did the same five minutes later.79 Just minutes into the return flight, near Bayonville, “Six enemy planes were encountered” by the planes of the 11th Aero, “and a running fight ensued, but the enemy planes were successfully driven away.”80 In retrospect, the squadron attributed their success to tight formation flying. “We did not believe there were any Huns in the air who could break into the tight formation we were flying at that time without having at least two or three times our number. This confidence was in striking contrast to the earlier feelings we all experienced when formation flying, as practiced on later raids, was so little known.”81 The successful formation flying on this raid is all the more remarkable as five of the thirteen planes were not able to reach the objective, so that the remaining eight planes would have had to maneuver to close up gaps.

The four-squadron mission of the afternoon set out at about 2:00; Stahl and Archer are listed among the thirteen teams from the 11th Aero. The unofficial history of the 11th Aero describes what happened after the squadrons bombed Bois-de-Barricourt and Bois-de-la-Folie:

As we turned over the objective and started for home a Hun patrol appeared. It was not particularly numerous and we were not much worried. They kept just out of range of our guns for some little time and finally decided that the 166th might be easier picking. They attacked, and to the amazement of everyone, broke up the entire formation of our fellow squadron. Things looked pretty rocky for a time and several of the machines were rather badly shot up before we could turn to their aid. As fast as possible we crossed above them and as soon as the Huns saw us in this position of advantage they promptly dropped the argument and turned for home.82

The 11th Aero’s plane no. 5, flown by Stahl and Archer, is listed as one of four that did not reach the objective.83 This is almost certainly an error. Plane no. 4, flown by Clifford Walter Allsopp, is listed among those that did reach the objective, but Allsopp’s log book records his having “turned back at lines”; it seems probable that Rath recorded the wrong plane number in his account of the mission. Furthermore, Stahl and Archer are credited with having shot down a plane over Imécourt—about two miles due south of the Bois-de-la-Folie—on this day.84 The more complete records of the morning raid do not mention a combat victory for the 11th, and it is reasonable to assume that it occurred on the less-well documented afternoon raid (although it is notable that the unofficial squadron history makes no mention of it). A decade after the war, when asked about this victory, Stahl didn’t “take much credit for it. ‘it was a running fight . . . and all I was doing was piloting the plane with my observer working the guns.’”85

Stahl and Archer next flew on October 29, 1918. On a morning mission, none of the planes of the 11th Aero reached the objective; the account of the operation does not show who was flying, so it is unknown whether Stahl was on this mission made up of planes from the 166th and the 11th.86 Stahl did fly, apparently as deputy flight leader to Oatis, with the 11th Aero in the afternoon as part of a four-squadron mission that targeted Damvillers; motor trouble kept him and Archer, along with three other teams (out of 12 or 13), from reaching the objective.87 Stahl was again deputy flight leader to Oatis on two missions the next day, and on both missions he and Archer reached the objective, Nouart in the morning and Belleville sur Bar in the afternoon.88

On the last day of October Stahl served as flight leader for eleven teams from the 11th Aero participating in a four-squadron mission that targeted Barricourt.89 Nine teams from the 11th, including Stahl with Archer in plane 12, “reached the objective and bombed, successfully cutting the road between Barricourt and Nouart.”90

No missions were flown on the first and second of November, and Stahl did not take part in the two missions on November 3, 1918, when Oatis served as the 11th’s flight leader. The next afternoon, however, Stahl, on his seventeenth (documented) mission, led the planes of the 11th Aero as part of a four-squadron mission tasked with bombing Montmédy—one of the targets initially and unrealistically proposed for the 1st Day Bombardment Group at the outset of the Meuse-Argonne Offensive. According to the narrative history of the First Day Bombardment Group, “Montmédy was most effectively bombarded by all formations and extraordinary and convincing photographs were taken of the work.”91

Stahl recalled his part in the mission a decade later:

. . . I started out to lead a raid. My motor had been acting up and Vincent Oatis, who wasn’t making the flight, told me to take his plane. It was the only one in the outfit equipped with the new “tin seat,” a sheet metal protection for the pilot. As we went over the lines 24 Hun planes soared down on the eight of us. Two of ours were shot down in flames, one of them only 40 feet from me. I felt my plane shaken violently. I thought an “Archie” (anti-aircraft shell) had exploded near me. But we came out of it and our six survivors made home safely in our DeHavilland 4’s, the famed flaming coffins. When I examined my plane I thanked the stars for that “tin seat.” An enemy bullet had struck it in the rear, leaving a grim imprint in the metal.92

Squadron and First Day Bombardment Group records often fail to record pilot’s plane numbers, but it appears that for some time Stahl flew no. 5 and Oatis no. 12.93 However, by the time Stahl served for the first time as flight leader on the last day of October, he and Oatis were sharing no. 12; John Lawrence Garlough flew no. 5 that day, after which there is no further record of it.

The 11th Aero’s raid report for the mission and the narrative history indicate that the attack by enemy planes took place as the nine teams (of twelve) that reached the objective dropped their bombs and were turning for home—Stahl perhaps meant “As we went [back] over the lines . . . ,” which by this day were in some places only about ten miles east of Montmédy. Tallies of the number of enemy planes vary, but it was certainly a large number.94 DH-4 no. 18, flown by Dana Edmund Coates with observer Loren Renfrew Thrall, and plane no. 6, flown by Gatton with observer George E. Bures, went down in flames to the west and northwest, respectively, of Montmédy.95

Stahl did not fly on the 11th Aero’s last mission the next day, when, in any case, they were unable to cross the lines.96 Six days later, the Armistice was signed. Stahl recalled that “Thanksgiving was a gala occasion with turkey obtained at fabulous prices and the rarest of French wines served.”97 He and Oatis made plans for a well-earned leave at Nice and Cannes.98 But “then on Dec. 5 came the order which started Jake and nine of his companions back to the United States and peacetimes.”99 Stahl and Oatis. sailed on the U.S.S. Princess Matoika from St. Nazaire on January 30, 1919, and arrived at Newport News, Virginia, on February 11, 1919. Princess Matoika.100

Stahl returned to Chicago and before settling in Evanston; he worked as an engineer at various companies.101

mrsmcq August 1, 2025

Notes

(For complete bibliographic entries, please consult the list of works and web pages cited.)

1 Stahl’s place and date of birth are taken from Ancestry.com, U.S., World War I Draft Registration Cards, 1917–1918, record for Walter A Stahl. His presumed place and date of death are taken from Ancestry.com, U.S., Social Security Death Index, 1935–Current, record for Walter Stahl. Unusually, I have found no more definite information regarding his death. The photo is from a photo of cadets at Christ Church College, Oxford University.

2 For information on Stahl’s family, see records, including census records, available at Ancestry.com.

3 [Ancestry.com], Missouri Synod, U.S., Lutheran Church records, 1851-1973, record for Walter Heinrich Andreas Stahl.

4 History of the 11th Aero Squadron U.S.A., p. 149.

5 The Semi-Centennial Alumni Record of the University of Illinois, p. 648.

6 Ibid.

7 Ibid.

8 See Stahl’s draft card, cited above.

9 “Brother of Mrs. Schweig Wins Cross.”

10 “Ground School Graduations [for September 1, 1917].”

11 Oatis, letter of July 17 [1917].

12 Oatis, letter of August 22, 1917.

13 “When Hell Broke Loose,” p. 9.

14 The National Archives (United Kingdom), Royal Air Force officers’ service records 1918–1919, record for Walter Andrew Stahl.

15 See Deetjen’s diary entry for February 28, 1918, regarding Pudrith and Middleditch being recommended for their commissions on January 15, 1917.

16 Cablegram 592-S.

17 Cablegram 813-R.

18 Curiously, Stahl’s name does not appear on either of two lists that recorded active duty dates for the cadets. See Biddle, “Special Orders No. 35,” and McAndrew, “Special Orders No. 205.”

19 This date appears on Stahl’s incident casualty card, “Stahl, W.A. (Walter Andrew).”

20 See his service record, cited above.

21 On the planes available at No. 44 T.S., see the relevant entry in Sturtivant, Hamlin, and Halley, Royal Air Force Flying Training and Support Units.

22 The quotation is from Oatis’s letter of May 18, 1918.

23 “When Hell Broke Loose,” p. 9.

24 Deetjen, diary entry for March 19, 1918.

25 Deetjen, diary entry for March 23, 1918.

26 Milnor, diary entry for April 24, 1918. (I assume that the “Red” to whom Milnor refers is Wheeler.)

27 “Stahl, W.A. (Walter Andrew).” This casualty card gives the name of Stahl’s passenger as “Burrell Wright,” as does the casualty card for Wright himself (“Wright, B. (Burrell”). The latter describes Wright as a private with the 135th Aero. The record for Wright in the lists of outgoing passengers at Ancestry.com, U.S., Army Transport Service Arriving and Departing Passenger Lists, 1910-1939, identifies Wright of the 135th Aero as the son of J. A. Wright of Baker, Oregon. Wright’s World War II draft card gives his full name; see Ancestry.com, U.S. WWII Draft Cards Young Men, 1940-1947, record for Burrill Everett Wright.

28 “When Hell Broke Loose,” p. 9.

29 Oatis, letter of May 18, 1918.

30 “When Hell Broke Loose,” p. 9.

31 See [Biddle?], “Special Orders No. 109,” and Coulter, “Special Orders No. 105.”

32 See “When Hell Broke Loose,” p. 9. I assume this article, written some ten years after the war, is inexact when it indicates that Stahl was ordered on July 4 from Marske to Clermont-Ferrand, and only later to Issoudun.

33 “When Hell Broke Loose,” p. 9, refers to “Otly,” which I take to be a mistranscription of Orly. Stahl’s observer, Hasell Davies Archer, mentions going from Clermont-Ferrand to “Arly [sic] . . . an aviation park about 5 miles from Paris”; see “Aviator Hasell Archer.”

34 Thomas, The First Team, p. 56 (I have not been able to review his source, S.O. No. 184); Tyler, Selections from the Letters and Diary, pp. 124–55; History of the 11th Aero Squadron U.S.A., p. 147. These sources imply that September 9, 1918, was the date of assignment to the 11th Aero, but Oatis’s letter and the squadron roster suggest otherwise. See also the counts of pilots and observers provided by Rath, “First Day Bombardment Group, Account of Operations,” for September 9 and 10, 1918.

35 “11th Squadron,” p. 4.

36 “First Day Bombardment Group,” p. 4.

37 Maurer, The U.S. Air Service in World War I, vol. 3, p. 120 (editorial comment).

38 Quotation is from William Mitchell’s Battle Orders No. 1, reproduced on pp. 137–40 of Maurer, The U.S. Air Service in World War I, vol. 3; here p. 140. See Thomas, The First Team, pp. 67–68, for a summary of the work of the 11th (and 20th) Aero on September 12 and 13, 1918. And see the entry for September 11, 1918, in Rath, First to Bomb: “Four teams from this group are to report in the morning to Hdq. to act as special couriers.”

39 In addition to the teams mentioned below, it appears that the fourth team consisted of Philip Newbold Rhinelander, pilot and Harry Campbell Preston, observer, both of the 20th Aero. See Barth, History of the Twentieth Aero Squadron, p. 33.

40 “When Hell Broke Loose,” p. 10.

41 Stahl recalled that neither team returned (“When Hell Broke Loose,” p. 10), but he evidently misremembered, for Cooper and Leonard did, only to be shot down over Verdun and became P.O.W.s on September 26, 1918. Crawford’s and Cooper’s respective P.O.W. accounts are reproduced in Presenting the Experiences of Air Service Officers who were Prisoners of War in Germany.

42 “When Hell Broke Loose,” p. 10. Stahl misremembered this as “the first day of the major St. Mihiel offensive.”

43 History of the 11th Aero Squadron U.S.A., p. 149.

44 History of Operations of 1st Army from Aug. 10 – Nov. 11 1918, p. 166; the report is reproduced on p. 354 of Maurer, The U.S. Air Service in World War I, vol. 3, where “Correl” is given as “Corral.” Neither version of the name, nor the name Stohl, appears in, for example, Sloan’s Wings of Honor.

45 Rath, First to Bomb, p. 91.

46 “Aviator Hasell Archer.”

47 See Groner’s account on p. 133–34 of Presenting the Experiences of Air Service Officers who were Prisoners of War in Germany, and History of the 11th Aero Squadron U.S.A., p. 151.

48 “11th Squadron,” p. 61. On leader and deputy leader, see Tyler’s diary entry for this day (Tyler, Selections from the Letters and Diary of John Cowperthwaite Tyler, p. 127). Rath, “First Day Bombardment Group, Account of Operations,” p. 94, provides a list of teams on this raid that is evidently incomplete, perhaps cut off at the bottom of the page, and inaccurate, perhaps not reflecting last minutes changes.

49 See Oatis’s letter of September 17, 1918.

49a See Rath, “First Day Bombardment Group, Account of Operations,” p. 99, as well as “11th Squadron,” pp. 10 and 11.

50 Norris, [History of operations of the 11th Squadron . . .], p. 54. Here as elsewhere accounts of individual missions differ: Rath, “First Day Bombardment Group, Account of Operations,” p. 99, states that “Not all of these planes reached the objective.”

50a Rath, “First Day Bombardment Group, Account of Operations,” pp. 100 and 102.

51 However, according to Rath’s diary entry for this day, he spotted planes of the 11th over Dommary, well beyond Conflans. Rath, First to Bomb, p. 101.

52 Rath, “First Day Bombardment Group, Account of Operations,” p. 100.

53 Rath, First to Bomb, p. 103 (diary entry for September 17, 1918).

54 Norris, [History of operations of the 11th Squadron during St. Mihiel Offensive], p. 54; see also the raid report on p. 65 of “11th Squadron.” Note: Thomas, The First Team, p. 79, indicates that the 11th did not fly this day (and History of the 11th Aero Squadron U.S.A., p. 153, is implicitly in agreement). Perhaps Norris was mistaken, or perhaps Thomas was unaware of the entry for this day in Norris’s History.

55 Rath, First to Bomb, p.104 (entry for September 18, 1918).

56 “When Hell Broke Loose,” p. 10, conflates the losses that occurred on these two days.

57 History of the 11th Aero Squadron U.S.A., p. 157

58 Information on Cooper is scarce, but I find no record of his having been attached to an R.A.F. squadron or of work with an American squadron prior to assignment to the 11th Aero. McCurry had been with the 8th Aero; the squadron documentation is insufficient to determine the extent of McCurry’s operational flying.

59 On Heater, see Skinner, “Commanding the 11th.” On the decision to use larger formations, see Maurer, The U.S. Air Service in World War I, vol. 1, p. 371.

60 From orders dated September 18, 1918, issued by Frank Purdy Lahm, reproduced in Maurer, The U.S. Air Service in World War I, vol. 2, pp. 238–40; here, p. 239.

61 Ibid.

62 See Thomas, The First Team, p. 89.

63 The memorandum is on p. 20 of “11th Squadron”; see Rath, “First Day Bombardment Group, Account of Operations,” pp. 106–09, for a record of the mission. NB: these pages have been compiled out of order.

64 Rath, “First Day Bombardment Group, Account of Operations,” p. 107; “11th Squadron,” p. 67.

65 History of the 11th Aero Squadron U.S.A., pp. 159, 161.

66 History of the 11th Aero Squadron U.S.A., p. 161. See also the standby memorandum on p. 22 of “11th Squadron,” and the list of teams on p. 110 of Rath, “First Day Bombardment Group, Account of Operations.”

67 Rath, First to Bomb, p. 110.

68 “11th Squadron,” pp. 55 and 69.

69 Rath, “First Day Bombardment Group, Account of Operations,” 111–12.

70 Rath, First to Bomb, p. 111.

71 Rath, “First Day Bombardment Group, Account of Operations,” pp. 113–14.

72 Rath, “First Day Bombardment Group, Account of Operations,” p. 115; History of the 11th Aero Squadron U.S.A., p. 163

73 Oatis, (transcription of) letter of October 7, 1918. It is probable, but not certain, that it is Stahl and Archer whom Oatis describes earlier in the paragraph as jokingly accusing one another of cowardice but never wanting to fly with anyone else.

74 History of the 11th Aero Squadron U.S.A., p. 165. Stahl’s landing place was presumably Courcelles-en-Barrois, about fourteen miles northeast of Maulan.

75 “War and Flapjacks.”

76 Rath, “First Day Bombardment Group, Account of Operations,” , pp. 125–28.

77 Rath, “First Day Bombardment Group, Account of Operations,” 129–30; “11th Squadron,” pp. 56 and 80.

78 First Day Bombardment Group, p. 5.

79 Rath, “First Day Bombardment Group, Account of Operations,” p. 131; “11th Squadron,” p. 81 (raid report); “History of the 20th Aero Squadron, 1st Army,” p. 232 (raid report).

80 Norris, [History of operations of the 11th Squadron during St. Mihiel Offensive], p. 56.

81 History of the 11th Aero Squadron U.S.A., p. 169.

82 History of the 11th Aero Squadron U.S.A., p. 169.

83 Rath, “First Day Bombardment Group, Account of Operations,” p. 132.

84 “Confirmed Victories 11th Aero Squadron,” p. 6.

85 “When Hell Broke Loose,” p.10.

86 Rath, “First Day Bombardment Group, Account of Operations,” p. 136, where for “(96th)”, read “(166th).”

87 Rath, “First Day Bombardment Group, Account of Operations,” p. 137; “11th Squadron,” p. 56.

88 Rath, “First Day Bombardment Group, Account of Operations,” pp. 138–39.

89 Ibid., p. 141.

90 “11th Squadron,” p. 57.

91 First Day Bombardment Group, p. 6.

92 “When Hell Broke Loose,” p. 10. Stahl describes this as having occurred “About the first of November,” and it fits as an account of the November 4, 1918, mission. That said, there are discrepancies (see below), and I may be mistaken in assuming the account refers to the mission of that date.

93 Rath, “First Day Bombardment Group, Account of Operations,” passim.

94 “11th Squadron,” pp. 57 and 89; see also History of the 11th Aero Squadron U.S.A., p. 175.

95 See “Coates. Dana E.”; “Thrall Loren R.”; “Gatton Cyrus J.” and “Bures, George E.” (burial cards).

96 Rath, “First Day Bombardment Group, Account of Operations,” p. 151.

97 “When Hell Broke Loose,” p. 10.

98 Oatis, letter of November 24, 1918.

99 “When Hell Broke Loose,” p. 10.

100 War Department. Office of the Quartermaster General. Army Transport Service, Lists of Incoming Passengers, 1917 – 1938, Passenger list . . . Princess Matoika.

101 See documents available at Ancestry.com.