(Pittsburgh, November 6, 1894 – San Francisco, April 15, 1936).1

Knox’s father, William Hugh Knox, was a Presbyterian Church pastor. Born in Ireland, the senior Knox came to Pittsburgh in 1861, where he attended Western University of Pennsylvania and the nearby Allegheny Theological Seminary.2 He married Fannie Kirkpatrick, also of Irish descent, and they had three children, of whom Walter was the youngest.

Knox attended Pittsburgh High School and then entered Princeton. A member of the class of 1917, he excelled in tennis.3 He was a student at the Princeton Aviation School, which had been established in the spring of 1917 to train Princeton students. He then became a member of the first class at the government run Princeton School of Military Aeronautics, which superseded the Aviation School in June 1917. He graduated from ground school there on August 25, 1917.4

Having, along with a number of other members of his ground school class, signed up to go to Italy for advanced training, Knox set sail from New York on the Carmania on September 18, 1917, as one of the 150 men of the “Italian” or “Second Oxford Detachment.” After a stopover at Halifax to join a convoy for the Atlantic crossing, the Carmania had an uneventful voyage and docked at Liverpool on October 2, 1917. There the men the learned that they would not proceed to Italy but would instead remain in England. They attended ground school (again) at the Royal Flying Corps’s No. 2 School of Military Aeronautics at Oxford. After some initial disgruntlement, the detachment made their peace with the change of plans and in retrospect recognized the benefit of R.F.C. training.

After a first night in Exeter College, the detachment was divided between Queen’s College and Christ Church. Knox roomed with his fellow Princetonians William Hamlin Neely and George Augustus Vaughn in Peckwater Quadrangle at the latter college until all the Americans were moved back to Exeter on October 22; there Neely and Knox shared a room with John Howard Raftery.5 As much of their class work repeated material already covered at ground schools in the U.S., the cadets (as they were now called) did not have to study hard; they enjoyed exploring Oxford and the surrounding countryside. Knox, along with Neely, Edmond Thomas Keenan, and Frank Aloysius Dixon (also Princeton students) toured the university and, towards the end of October, enjoyed a bicycle ride to Abingdon, a few miles south of Oxford, at the conclusion of which Dixon and Knox (despite Knox’s being, according to the Nassau Herald, a “prohibitionist”6) “imbibed quite heavily & consequently felt very hilarious.”7

A few days later the cadets learned that most of them would be sent from Oxford to Grantham in Lincolnshire to attend machine gun school at Harrowby Camp. Twenty cadets were to go to Stamford twenty miles to the south to begin actual flight training. The lucky few had been selected by Elliott White Springs, in part on the basis of their having already had, like him, some flying experience at Princeton. Although Springs chose Dixon, Neely, and Vaughn, Knox was among the 129 who left on November 3, 1917, for Grantham.8

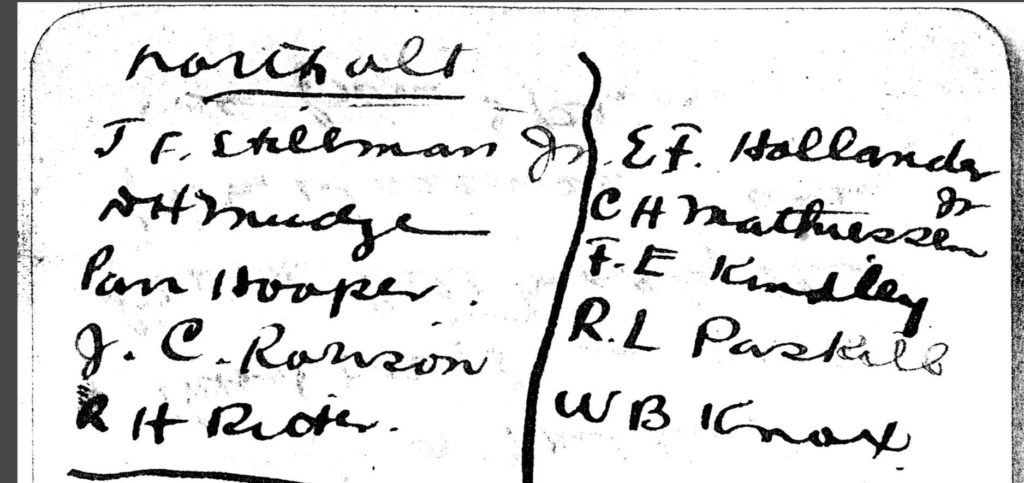

His time there was relatively short, for on November 19, 1917, another selection was made, this time of fifty men to be sent on to various training squadrons around England. Knox was one of the ten cadets sent to Northolt, on the northwest outskirts of London, where five men trained at No. 2 Training Squadron and five, including Knox, at No. 4 T.S.9 The instructional plane used at Northolt was the ubiquitous Maurice Farman S.11, and this would have been the plane Knox initially trained on.

Knox’s R.A.F. service record shows him assigned to No. 65 Training Squadron at Dover on December 28, 1917; three days later, on the last day of the year, he was reassigned to No. 40 T.S. at Croydon on London’s southern outskirts. Both No. 65 and No. 40 trained pilots to fly Sopwith Camels. Knox had a long way to go before flying an operational plane, but the assignments suggest he had already been earmarked for Camels. After flying Maurice Farmans, Knox moved on to the next training plane, the Avro, and then flew Sopwith Pups, and finally Camels.10

By the end of March Knox had advanced sufficiently in his training at Croydon to be recommended for a commission. Pershing’s cablegram forwarding Knox’s and other recommendations to Washington is dated March 29, 1918.11 When, by the end of April, approval of the recommendations had not been received, a follow-up was sent (“Request action taken on paragraph 3 A my cablegram 811″).12 Finally, on May 17, 1918, Washington cabled back that the relevant appointments had been made.13 From Croydon, Knox was sent to Turnberry for training in aerial gunnery.14 On June 1, 1918, he was put on active duty, and during that month he served as a ferry pilot, flying planes to France at least twice.15

In early July 1918 Knox was assigned to an operational squadron. He reported to the U.S. 148th Aero Squadron on July 4, 1918, along with his fellow second Oxford detachment members Marvin Kent Curtis, Linn Humphrey Forster, and John Hurtman Fulford.16 The 148th was stationed at the Capelle airdrome near Dunkirk, not far from the U. S. 17th Aero Squadron at Petite Synthe. Both 17 and 148 flew Camels, and, although American in personnel, they were stationed on the British Front and under the tactical command of the R.A.F. until late in the war. Knox was apparently assigned to A flight, led by first Oxford detachment member Bennett Oliver. Oliver would be replaced as flight leader by second Oxford detachment member Field Eugene Kindley around August 1, 1918.

During July, the pilots of the 148th initially got to know their machines and their territory. William P. Taylor, the squadron historian, describes their activities:

. . . line patrols were soon started and after careful study of the map showing this sector, from the coast at Nieuport down to Ypres, most of it flat, marshy country where the line had been permanent for four years, the patrol leaders took their charges up to the edge of that awesome place, “Hunland,” and let them look it over. As aerial activity was comparatively quiet on this front, few Huns were sighted and day after day the line patrols were practiced without an attempt yet at offensive work. . . . After a week or more of line patrols the first offensive patrol over lines was made on July 20th, that of escorting the British “De Haviland-9″ bombing planes far over the lines to bomb the Belgian coast cities of Zerbrugge, and Ostend and also Bruges, inland some distance and over twenty-five miles into “Hunland.” The first escorting trip across the lines was made to Bruges and to many of the pilots it was the baptism of fire as the “Archie” bursts were continuous during the entire trip.17

These line and escort patrols were largely uneventful until early August. On August 3, 1918, the escort, which consisted of A and B flights, encountered, as William Thomas Clements of B flight described it,

a little excitement today. We accompanied the bombers over to Bruges. . . . After a rather disagreeable trip there, dodging Archie, and the bombers had dropped their bombs, we turned for home. Four Fokkers biplanes appeared out of a blue sky and immediately sat upon our tail. There were nine camels so they did not care to get down on our level, and we could not get up to theirs. They followed us for about 5 miles waiting for someone to straggle. Someone did and one of the Fokkers went down on him. Our entire bunch of camels turned and went down on the Fokker.18

Assuming that Knox, as a member of A flight, participated in this mission, this would have been his first experience of aerial combat. His flight leader, Kindley, successfully claimed a Fokker destroyed, as did Springs of B flight.

Squadron historian Taylor recounts how “After three weeks of war-flying on the Nieuport-Ypres Front, . . . Major Fowler, who was now in charge of the American Air Forces with the British, asked that [the squadron] be transferred to a more active front. . . . Major Fowler’s request was acceded to, and on August 11th the Squadron was ordered to Allonville Airdrome or Horse Shoe Woods, as it was called, near Amiens,” some seventy-five miles south of Dunkirk.19 The squadron was now attached to the 22nd Wing, V Brigade, R.A.F., supporting the British Fourth Army, commanded by General Henry Rawlinson.20 The Fourth Army, operating on the front from Albert to Roye, had since August 8, 1918, been in the forefront of the Battle of Amiens, the opening push of the Allies’ Hundred Days Offensive. The 148th arrived too late to participate in the major combat of the Amiens offensive, but it was nonetheless now on a far more active front than the one they had just left.

The 148th remained at Allonville for a week. The pilots flew patrols from Albert south to Roye and Montdidier daily, sometimes twice daily, and engaged in at least five combats.21 On August 18, 1918, the 148th was ordered to Remaisnil, about seventeen miles to the north, where they were attached to the British Third Army, commanded by General Sir Julian Byng.22 As the Third Army began its push eastwards, the 148th, starting on August 22, 1918, undertook, in addition to their escort duties and offensive patrols, the particularly dangerous work of low bombing and ground strafing.

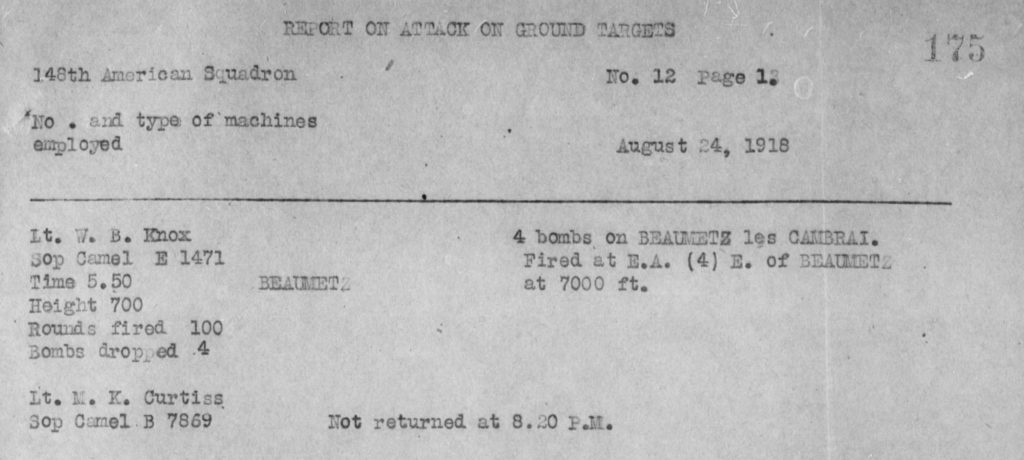

Knox took part in his first bombing mission, the squadron’s fourth, on August 24, 1918, in the early afternoon. It was a two-man raid; the other pilot was A flight pilot George Vaughn Seibold. Knox was flying Camel E1471, which had a bad compass, and, having gotten lost, he had to return without dropping any bombs.23 He set out again just before 6:00 p.m. and was able to drop four bombs on Beaumetz-lès-Cambrai, about eleven miles west-southwest of Cambrai, and “Fired at E.A. (4) E. of Beaumetz at 7000 ft.”24 Any satisfaction at a mission successfully accomplished must have been tempered by the fact that his partner on this mission, Curtis, had “Not returned at 8.20 PM.”25 For a time the worst was feared: that Curtis had gone down in flames, but he had, in fact, crash landed in German-held territory and been taken prisoner.

Knox flew bombing and strafing missions on August 25, 26, and 31, and on September 1 (two missions), flying four different planes on the five raids, which targeted towns and troops between Bapaume and Cambrai.26 By September, significant advances had been made on the Third Amy’s section of the front, and Bapaume had been retaken. On September 2, 1918, the Allied focus shifted north, as a successful push was made to break the German defensive line between Drocourt and Quéant (the “Drocourt–Quéant switch line,” part of the Hindenburg line), running north to south across the major road between Arras and Cambrai. The 148th Aero was one of a number of squadrons assisting the effort. A and B flights set out at 11:00 a.m. on an offensive patrol and bombing raid in the vicinity of Rumaucourt.27 On their return journey, about forty-five minutes later, A flight, led by Kindley, was ahead, when Springs’s B flight, still in the vicinity of the Canal du Nord, realized that British planes were being attacked by Fokkers and went to their aid.28 Kindley then led A flight back to assist as well. It appears that as many as five German planes were shot down in the ensuing encounter, but at a great cost.29 Three pilots from B flight, Forster, Oscar Mandel, and Johnson Darby Kenyon, failed to return from the mission, and two pilots from A flight, Joseph Edwin Frobisher, Jr., and Jesse Orin Creech, were forced to land; Forster and Frobisher died. The three remaining A flight pilots, Charles Ingoldsby McLean, Kindley, and Knox were each credited with a victory.30 Knox, who was flying the plane he had flown the preceding day, F5946, recorded being so close when he fired at the enemy aircraft that he saw the pilot “fall forward in the cockpit.”31

Knox flew bombing and strafing missions on August 25, 26, and 31, and on September 1 (two missions), flying four different planes on the five raids, which targeted towns and troops between Bapaume and Cambrai.26 By September, significant advances had been made on the Third Amy’s section of the front, and Bapaume had been retaken. On September 2, 1918, the Allied focus shifted north, as a successful push was made to break the German defensive line between Drocourt and Quéant (the “Drocourt–Quéant switch line,” part of the Hindenburg line), running north to south across the major road between Arras and Cambrai. The 148th Aero was one of a number of squadrons assisting the effort. A and B flights set out at 11:00 a.m. on an offensive patrol and bombing raid in the vicinity of Rumaucourt.27 On their return journey, about forty-five minutes later, A flight, led by Kindley, was ahead, when Springs’s B flight, still in the vicinity of the Canal du Nord, realized that British planes were being attacked by Fokkers and went to their aid.28 Kindley then led A flight back to assist as well. It appears that as many as five German planes were shot down in the ensuing encounter, but at a great cost.29 Three pilots from B flight, Forster, Oscar Mandel, and Johnson Darby Kenyon, failed to return from the mission, and two pilots from A flight, Joseph Edwin Frobisher, Jr., and Jesse Orin Creech, were forced to land; Forster and Frobisher died. The three remaining A flight pilots, Charles Ingoldsby McLean, Kindley, and Knox were each credited with a victory.30 Knox, who was flying the plane he had flown the preceding day, F5946, recorded being so close when he fired at the enemy aircraft that he saw the pilot “fall forward in the cockpit.”31

For the next three weeks the 148th apparently focused on offensive patrols when the weather permitted, rather than strafing and bombing raids.32 As squadron historian Taylor does not provide details of these patrols in his history, information on Knox’s participation is indirect. Kindley filed a combat report on September 5, 1918, as did Jesse Creech (also of A flight) on September 6, 1918, indicating that A flight flew missions those days. Weather kept the 148th grounded from the 8th through the 12th, but flights resumed the next day, and on September 15 and 17, 1918, there are combat reports from A flight’s Kindley or Creech or both.33

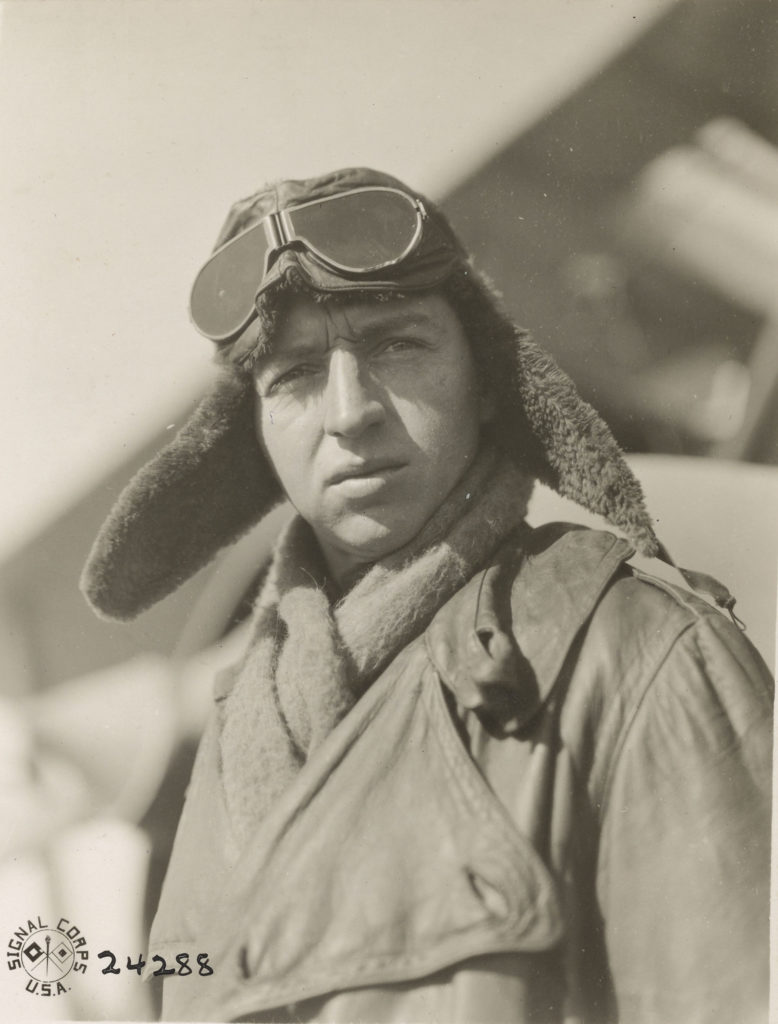

In the meantime Signal Corps photographer Edward Otto Harrs was at Remaisnil and took many photos of the pilots of the 148th, including several of Knox, and a well-known one of A flight as it was constituted on September 14, 1918: Lawrence Theodore Wyly, Louis William Rabe, Kindley (with his dog, Fokker), Knox, and Creech.34

As the German armies fell back to the east, the flying distance from Resmaisnil to the front lines increased, and on September 20, 1918, the 148th Aero moved east to an airdrome at Baizieux, near Albert. Here they shared patrols with No. 60 Squadron R.A.F., whose S.E.5a’s provided the “‘upper guard,’ while 148 flew low, bombing troops and attacking low-flying Fokkers.”35 Knox took part in the first of the 148th’s attacks on ground targets out of Baizieux in the early morning of September 22, 1918, flying Camel D6249; the target was Marcoing, about five miles southwest of Cambrai. There were seven other planes in the formation, which was made up of the five pilots of A flight and three from C.36 Whereas bombing and strafing raids out of Remaisnil had often been conducted by teams of two or four pilots, the ones out of Baizieux were typically larger, often consisting of formations of thirteen or fifteen planes.

The 148th was also still conducting higher altitude offensive patrols. On September 24, 1918, a number of the pilots of the 148th, including Knox, had the “Best fight these pilots were ever in.”37 With an R.A.F. squadron, presumably No. 60 R.A.F., flying protection above them, the three flights from the 148th set out from Remaisnil around 7:00 in the morning and flew east towards Cambrai, about forty-five miles away.38 Near Bourlon Wood, a few miles over the lines, C flight, flying beneath the other two, encountered and engaged a flight of seven “blue-tail” Fokkers. The planes of A flight, and then those of B flight, dove down to assist.39 According to his combat report, Knox, flying Camel C3310 at 11,000 feet, shot at four Fokkers at 7:40 a.m. and followed one down to 3,000 feet to see him crash. This, Knox’s second victory, was one of the seven credited to the squadron that day.40 More Fokkers joined the combat, which, according to one pilot, lasted thirty minutes; Springs afterwards reported that men on the ground had counted fifty-three German planes.41 Although many of the 148th’s planes were damaged, some badly, the squadron sustained no casualties beyond one pilot’s suffering “a slight concussion.”42 Later in the morning the 17th Aero Squadron, also now assigned to the 13th Wing, had a similar encounter with the “blue-tail” Fokkers with similar success, and congratulations from the highest levels of both British and American aviation added to the squadrons’ celebrations.43

Francis L. “Spike” Irvin, one of the enlisted men of the 148th, noted the seven victories in his diary that day and also: “Push on Cambrai expected.”44 The U.S. 148th Squadron was part of a concentration of Allied air power supporting the effort to take Cambrai. “The work now resolved itself into patrol after patrol ‘with bombs’ and with orders to shoot up targets on the ground with the machine guns. In all sorts of weather, cloudy, misty, rainy or fair, the flights went out at low altitudes to perform their work.”45 Between September 27 and October 12, 1918, Knox, flying C3310, took part in at least fourteen attacks on enemy ground targets, sometimes flying two in a day.46

September 27, 1918, marked the opening of the Battle of the Canal du Nord, the successful attack by the British First and Third Armies on a stretch of the formidable Hindenburg Line about seven miles to the west of Cambrai. The orders for the 148th during the attack specified their working with No. 60 Squadron R.A.F. and focussing, at least initially, on ground targets: “No. 148 American Squadron to work below No. 60 Squadron, and bombs will be carried by No. 148 American Squadron, whose lowest flight should work not above 3,000 feet at the commencement of the patrol. Suitable ground targets such as troops, transport or guns will be attacked. Approaches to the crossings of the Canal de L’Escault and all sunken roads should be specially looked at. Crossings themselves should not be bombed.”47

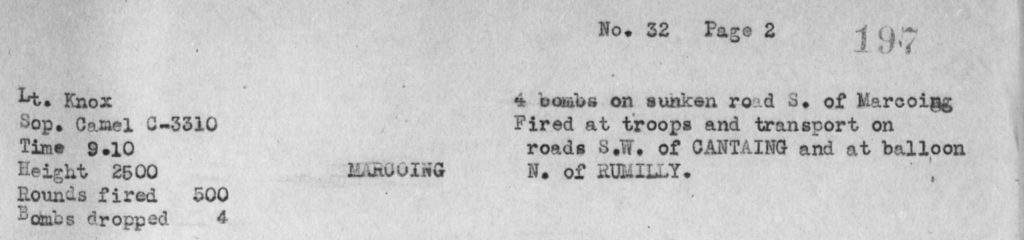

On the 27th, around 8:40 a.m., thirteen pilots from the 148th took off, escorted by planes from No. 60 Squadron R.A.F.48 At 9:10 Knox and Kindley each dropped four bombs on a sunken road south of Marcoing and then fired on troops southwest of Cantaing before attacking a balloon north of Rumilly.

The other pilots variously targeted transport, troops, railway sidings, and balloons in the vicinity of Marcoing and Rumilly; all planes from both squadrons, No. 60 and the 148th, returned safely to Baizieux.49

Early the next morning Knox was one of fifteen pilots from the 148th on a strafing raid targeting troops and transport southwest of Cambrai. The targets named in Knox’s subsequent bombing reports document the eastward movement of Byng’s army. Squadron historian Taylor describes how “Gradually the British pushed the Huns back toward Cambrai. . . . For a while the line bent around Cambrai on each side but the Huns still held the city. Then it was that the squadron was sent over to do low reconnaisance [sic] as well as the usual bombing. They scanned the roads leading into Cambrai from the East for the signs of the evacuation of the city and dropped their bombs on the troops and transport who were seen making their way toward Le Cateau [fourteen miles east-southeast of Cambrai]. . . . Then when the Hun could hold the city no longer the lines straightened out miles to the east and the advance continued.”50 By nightfall on October 9, 1918, “Cambrai was three miles inside the British area.”51 That day Knox had been one of five pilots from the 148th who dropped bombs in the vicinity of Estournel, southeast of Cambrai on the road to Le Cateau, and provided a report of explosions, fires, and enemy transport movement.52

On October 12, 1918, Knox apparently flew his last mission. Along with three other pilots he dropped bombs on Villers-en-Cauchies, five miles to the northwest of Cambrai.53 On this day, also, he experienced his first (documented) crash: “Struck tree top landing in ground mist, on nose.” He was unhurt, but his Camel needed repair.54 This may account for Knox’s not participating in the next and last raid flown by the 148th out of Baizieux on October 14, 1918. That day, with Cambrai taken and the Allies advancing eastwards, the 148th once again, along with No. 60 Squadron, relocated. Their new station was the air field at Beugnâtre, about two miles northeast of Bapaume—Bapaume now “a cluster of ruins in the middle of a desert,” in squadron historian Taylor’s words.55 The 148th appears to have flown no further bombing raids until October 21, 1918, by which time Knox had set off for England on leave. The leave was scheduled to run from October 18 until October 31, 1918. Knox did not rejoin the squadron until November 5, no doubt because he had had to chase them to their new location at Toul on the American front, where they had been ordered on November 1, 1918.56 It was about four days uncomfortable train journey for the 148th from their aerodrome on the British Front to Toul; Knox arrived a day after they did. At Toul the 148th, now attached to the American Second Army, celebrated the armistice and then settled in to wait for transport home. During their time at Toul the 148th, like other American squadrons, had photos taken.

Knox sailed for the U.S. on the S.S. Stockholm, which left Brest on February 2, 1919, and arrived at New York ten days later.57 He returned to Pittsburgh and became a partner with his brother, George Hackett Knox, in the Knox & Knox Insurance Company. 58

mrsmcq September 17, 2018

Notes

(For complete bibliographic entries, please consult the list of works and web pages cited.)

1 Knox’s place and date of birth are taken from Ancestry.com, U.S., World War I Draft Registration Cards, 1917–1918, record for Walter Burnside Knox. For his place and date of death, see “Walter Burnside Knox ’17” and “Man Found Dead of Bullet Wound.” Obituaries in Pittsburgh papers indicate, apparently erroneously, that the death occurred on April 17, 1936. The photo is a detail from one taken at Remaisnil on September 15, 1918 (NARA 111-SC-24286).

2 “The Rev. William Hugh Knox.”

3 See, for example, “Knox Wins Title” and the entry for Knox on pp. 153–54 of The Nassau Herald: Class of Nineteen Hundred and Sixteen.

4 See The Princeton Bric-a-Brac 1919, pp. 85-87, and “Ground School Graduations [for August 25, 1917].”

5 Information in this paragraph comes from entries in Neely’s diary for the month of October.

6 See The Nassau Herald: Class of Nineteen Hundred and Sixteen, p. 154.

7 Neely, diary entry for October 28, 1917.

8 See The National Archives (UK), Royal Air Force officers’ service records 1918–1919, record for Walter Burnside Knox. The list on p. 28 of Vaughn, War Flying in France, of men sent to Stamford, which includes Knox, is not accurate. According to the War Birds entry for November 6, 1917, one man, James Whitworth Stokes, remained in Oxford to be operated on for appendicitis.

9 See Foss, diary entry for November 15, 1917, which lists the men leaving Grantham, along with their assignments, and see Knox’s R.A.F. service record, cited above.

10 See Knox’s R.A.F. service record, cited above.

11 Cablegram 811-S.

12 Cablegram 1029-S.

13 Cablegram 1337-R.

14 Ancestry.com, Pennsylvania, WWI Veterans Service and Compensation Files, 1917–1919, 1934–1948, record for Walter Burnside Knox.

15 McAndrew, “Special Orders No. 205”; Sturtivant and Page, The Camel File, entries for Camels F1340 and F1356.

16 Taylor, A History of the 148th Aero Squadron, pp. 61 and 62.

17 Taylor, A History of the 148th Aero Squadron, pp. 26 & 27.

18 Clements, “World War Diary of W. T. Clements 1917-1918,” entry for August 3, 1918.

19 Taylor, A History of the 148th Aero Squadron, p. 28.

20 On the 148th, the Fourth Army, and the 22nd Wing, see Taylor, A History of the 148th Aero Squadron, pp. 29 and 79; see also Jones, The War in the Air, vol. 6, p. 469. Taylor’s history reproduced in Taylor and Irvin, Francis L. “Spike” Irvin’s War Diary and The History of the 148th Aero Squadron Aviation Section, inadvertently, p. 26, puts the 148th at Allonville with the Third British Army, and this was presumably the source of confusion for Skelton and Williams on p. 98 of their biography of Henry R. Clay.

21 See the transcription of Springs’s log book for this period on pp. 198, 200, and 202 of Springs, Letters from a War Bird. I have not found anything like a squadron record book with records of all flights made by the 148th.

22 Taylor, A History of the 148th Aero Squadron, p. 31.

23 Ibid., p. 167.

24 Ibid., p. 175.

25 Ibid.

26 Ibid., pp. 179, 183, 185, 188, and 191.

27 For the start time, see the entries for pilots of the U.S. 148th on pp. 214–15 of Henshaw, The Sky Their Battlefield II. Bomb report number 28, which may have described this mission, is lacking in both Taylor, A History of the 148thAero Squadron (in Gorrell), and in that text in Taylor and Irvin, Francis L. “Spike” Irvin’s War Diary and The History of the 148th Aero Squadron Aviation Section.

28 Jones, The War in the Air, vol. 6, p. 498, identifies the British planes as S.E.5a’s from No. 64 Squadron and Bristol Fighters from No. 22 Squadron.

29 See Henshaw, The Sky Their Battlefield II, p. 215.

30 The combat reports reproduced on pp. 118–20 of Individual Combat Records of Pilots with R.A.F. credit each fo the three pilots with a destroyed E.A. Knox’s report reproduced on p. 118 of Taylor, A History of the 148th Aero Squadron, credits him with a plane driven down out of control.

31 Combat report on p. 118 of Taylor, A History of the 148th Aero Squadron.

32 See the bombing reports in Taylor, A History of the 148th Aero Squadron, which jump from No. 27 on September 1, 1918, to No. 29 on September 16, 1918 (pp. 191–92; No. 28, presumably for September 2, 1918, is missing). Spike Irvin’s diary notes offensive patrols during this period; see Taylor and Irvin, Francis L. “Spike” Irvin’s War Diary and The History of the 148th Aero Squadron Aviation Section, pp. 16–18.

33 See the combat reports in Taylor, A History of the 148th Aero Squadron, pp. 122, 123, 124, 129, and 134. And see Irvin’s diary (cited above) for this period; his entry for September 14, 1918, refers to a victory by Kindley that is not reflected in the combat reports—perhaps he recorded it under the wrong day.

34 See Catalogue of Official A.E.F. Photographs Taken by the Signal Corps, pp. 274, for photos [111-SC-] 24284–88.

35 Scott, Sixty Squadron R.A.F., p. 117. On the 148th’s cooperation with 60 as well as with No. 201 Squadron R.A.F. at Baizieux, see also Taylor, A History of the 148th Aero Squadron, p. 36. On the initiation of and rationale for these two squadron patrols, see Jones, The War in the Air, vol. 6, pp. 506–07.

36 Taylor, A History of the 148th Aero Squadron, pp. 194–95.

37 Irvin, diary entry for September 24, 1918 (Taylor and Irvin, Francis L. “Spike” Irvin’s War Diary and The History of the 148th Aero Squadron Aviation Section, p. 17).

38 On September 25, 1918, C flight leader Clay wrote: “yesterday, I led a patrol of 14 machines from our squadron and 15 from another which worked above us” (Skelton and Williams, Lt. Henry R. Clay, p. 128).

39 On the possible identity of these enemy planes, see “Blue-tail Fokkers, Sept. 24, 1918.”

40 See combat reports on pp. 136–42 of Taylor, A History of the 148th Aero Squadron and the narrative account on pp. 39–40.

41 Skelton and Williams, Lt. Henry R. Clay, p. 128; Springs, Letters from a War Bird, p. 243.

42 See Irvin’s diary, cited above, p. 17; the injured pilot was Errol Henry Zistel.

43 Taylor, A History of the 148th Aero Squadron, p. 40. See “Blue-tail Fokkers” on the corresponding German casualties (or lack thereof).

44 See Irvin’s diary, cited above, p. 17.

45 Taylor, A History of the 148th Aero Squadron, p. 40.

46 See the reports of the attacks on enemy ground targets on pp. 196–235 in Taylor, A History of the 148th Aero Squadron. P. 220, report No. 43 (October 4, 1918), includes Knox’s name but no details, and it may be that his name is there in error.

47 Playfair, 13th Wing Special Operation Order No. 12.

48 Hudson, “Captain Field E. Kindley,” p. 22, provides the time, based on an account by Kindley titled “A Day in France” in the Kindley Records File.

49 See pp. 196–97 of Taylor, A History of the 148th Aero Squadron (report no. 32), and pp. 39–40 for a narrative account.

50 Ibid., p. 41.

51 Jones, The War in the Air, vol. 6, p. 538.

52 Taylor, A History of the 148th Aero Squadron, p. 232 (report no. 50).

53 Ibid., p. 235 (report no. 53); the map reference provided (51A U6 A61) points to Villers-en-Cauchies; see Great Britain, War Office, Geographical Section, General Staff, [Valenciennes].

54 See entry for Camel C3310 in Sturtivant and Page, The Camel File.

55 Taylor, A History of the 148th Aero Squadron, quotation taken from p. 41; date from p. 42.

56 Ibid., pp. 17–18,

57 War Department, Office of the Quartermaster General, Army Transport Service, Lists of Incoming Passengers, 1917 – 1938, Passenger list for the S.S. Stockholm.

58 See documents available at Ancestry.com.