(Rapid City, South Dakota, March 15, 1895 – Chicago, February 3, 1932).1

Halley’s grandfather, James Halley, came to the U.S. from Scotland in about 1856 and was working on the C&O Canal when he sent for his family to join him. They settled in Washington, D.C. One of his sons, James Halley II, became a telegraph operator in Wyoming and later a banker in Rapid City, South Dakota, where Walter was born, the eighth of nine children.2

Halley attended the Harvard Military Academy in Los Angeles and entered Cornell University with the class of 1917. He completed three years and then enlisted in the army in April 1917.3 He transferred to the Aviation Section of the Signal Corps and attended ground school at the University of Illinois, graduating August 25, 1917.4

About one third of the men in this class, including Halley, chose or were chosen to go to Italy for flight training and were thus among the 150 men of the “Italian” or “second Oxford detachment” who sailed to England on the Carmania. They departed New York on September 18, 1917, and, after a stopover at Halifax to meet up with a convoy for the Atlantic crossing, docked at Liverpool on October 2, 1917. There they learned that they would not proceed to Italy, but would remain in England and attend ground school, again, this time at the Royal Flying Corps’s No. 2 School of Military Aeronautics at Oxford University. Once arrived at Oxford, Halley was able to room with men he knew from Illinois’s School of Military Aeronautics: John Warren Leach, George Orrin Middleditch, and Chester Albert Pudrith.4a After some initial disgruntlement, the detachment made their peace with the change of plans and in retrospect recognized the benefit of R.F.C. training. They enjoyed the beauties of an Oxford autumn and took advantage of their proximity to London to sightsee, shop, dine, and attend the theater. It was perhaps during such an excursion that Halley “was an interested spectator of the air raid of October 29th,” when a German Gotha bomber made a nighttime raid on Essex: “he was not near the scene, but he was near enough to know that he did not want to be any nearer.”5

On November 3, 1917, Halley travelled with most of the detachment to Harrowby Camp near Grantham in Lincolnshire to attend machine gun school. He initially trained with a group that included Joseph Kirkbride Milnor, who kept a photo of them. While fifty of the men at Grantham were sent on to flying schools on November 19, 1917, the rest, including Halley, continued their course at Harrowby Camp through the end of November.

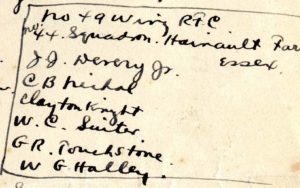

Finally, on December 3, 1917, the remaining men at Grantham were posted to flying squadrons, and Halley, along with John Joseph Devery, Clayton Knight, Clark Brockway Nichol, Wilbur Carleton Suiter, and Grady Russell Touchstone, was assigned to No. 44 Squadron at Hainault Farm northeast of London.6 No. 44 was a home defense squadron; it pioneered the use of Camels at night as part of the London Air Defense Area. Shortly after his arrival, Halley “had the privilege of seeing an air raid at fairly close quarters. . . . It would have been quite thrilling if it hadn’t been at such an ungodly hour of the morning.”7 Indeed, this raid on December 6, 1917, much larger and more lethal than the one in October, began targeting Kent, Essex, and London around 2:00 a.m. Halley learned from the next day’s newspapers that “a couple of the Hun machines were brought down before they could get away”—there is a record of two Gothas having been brought down by antiaircraft fire.8

Winter weather meant German raids became less frequent, but it also restricted flight time for Halley and his fellow cadets: “The bad days are overwhelmingly in the majority . . . so most of our work is inside. Have had a little joy-riding during what nice weather we have had.”9 Needless to say, Halley and his fellow trainees did not receive instruction on Camels (single-seaters, notoriously difficult for inexperienced fliers), but rather on a B.E.2c that was available at the airfield.10 The B.E.2c was a two-seater, originally designed for reconnaissance and bombing, but by this time obsolete. Halley wrote of his first flight: “My first ride was a corker. We didn’t do it by degrees a bit, but jumped in and got wet all over first time up but didn’t mind it a bit, in fact was pretty tickled to get all the sensations gettable right off the bat. We looped the loop, side-slipped, did spiral nosedives and all sorts of peculiar antics. Am looking forward now to the time when I will be able to do them as pilot instead of simply as a passenger.”11

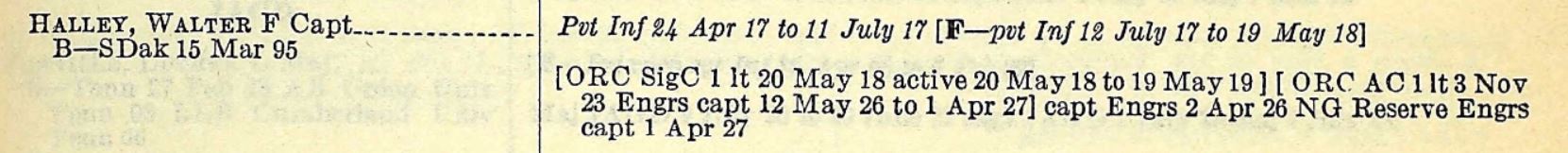

At some point in January 1918 the six Americans at No. 44 Squadron were “posted away to a regular flying training unit at Stamford.”12 Halley progressed fairly quickly through the initial stages of his training and by the latter part of March was recommended for his commission—his was among the many recommended in ten cables from Pershing between March 30 and May 4, 1918, that were finally confirmed en masse on May 13, 1918.13 Halley’s commission became official on May 20, 1918.14

Meanwhile, he “had a week’s graduation leave in London about the end of March and spent most of the time just loafing an[d] taking things easy. Went to a few shows—the only one that amounted to anything was ‘The Maid of the Mountains,’ and it had some mighty good music.”15 While Clayton Knight continued his training at Stamford,16 Halley was reassigned: “A few days after I got back from leave was transferred to another airdrome to go on more advanced machines.”17 Although he does not name his new station in his letter home, Halley notes in passing “a little panel in the wall of a house in the town where we are stationed to the effect that William Cowper lived there from 1765 to 1767,” i.e., in Huntingdon in Cambridgeshire.18 “Our billets are a little way from the town but close enough so that we can walk in occasionally and have dinner and a good smoke and chat in the inn ‘lounge’ afterward.”19 The billets were perhaps in nearby Wyton, and Halley was probably assigned to No. 5 or No. 31 Training Squadron there. It was presumably around this time that his future as a pilot of bomber and reconnaissance planes was determined. At Huntingdon he ran into a fellow Cornellian, Guy Brown Wiser, who later recalled that “The DH-4 . . . was used as a graduation test at Wyton Base, Huntingdon, England. . . .”20 In a later letter, Halley writes that “I only wish I were driving a fighting scout instead of one of the big bombers as the bombing machines do not have much chance to do fighting and I certainly would like to bag a few Hun machines.”21

There is no indication whether this last letter was written from Huntingdon or whether by this time Halley had again been reassigned. At some point he was sent to Marske-by-the-Sea in North Yorkshire. There is no indication of the length of his stay there or what the training consisted of. In early July 1918 he and fellow second Oxford detachment member Allen Tracy Bird, along with Harold Ernest Goettler and Claude Stokes Garrett, both of whom had trained with the R.F.C. in Canada, were ordered to travel from Marske to London, preparatory to going overseas.22 By July 4, 1918, Halley was in London with Goettler, “bumming around town visiting the Regent Palace and the Savoy Hotel.”23 Halley was one of a large group of pilots directed to report to the American 3rd Aviation Instruction Center at Issoudun in the Loire region of central France, where they arrived on July 10, 1918.24

Halley’s next documented posting was to the American 7th Aviation Instruction Center at Clermont-Ferrand in France, where he served “as flying instructor in gunnery-combat, acrobatics, etc.”25 The 7th A.I.C. served as a bombardment training school, and Halley presumably flew DH-4s. On November 4, 1918, he was assigned to the U.S. 11th Aero, stationed at Maulan and flying DH-4s as part of the 1st Day Bombardment Group.26 He is not among those who flew missions on November 4 and 5, 1918, and the 11th flew no further missions before the armistice.27

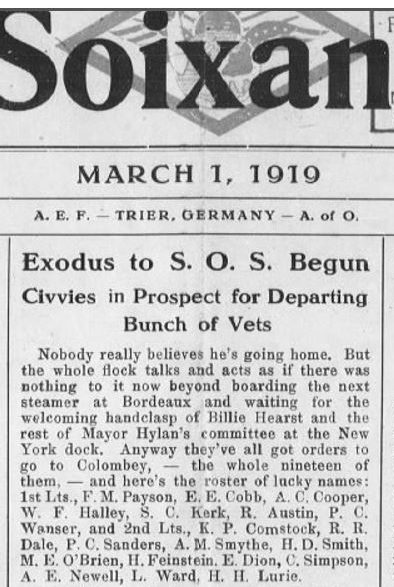

At some point after the armistice Halley was reassigned to the 166th Aero, which became part of the Army of Occupation and was stationed at Trier and Coblenz.28 At the end of February 1919 he was among those in the 166th who received orders to proceed to Colombey-les-Belles in anticipation of returning to the U.S.29 Along with Tracy Bird, he sailed from Brest on the S. S. Suriname on April 4, 1919, arriving at Hoboken on April 29, 1919.30

Having returned to South Dakota, Halley initially worked at his father’s bank.31 In the late twenties he went into business with his brother Samuel Russell Halley (who had served with a French squadron in 1918) to create airline service in South Dakota and neighboring states. They also for a time ran the Black Hills College of Aviation in conjunction with their Rapid Air Lines Corporation.32

mrsmcq October 5, 2017; revised February 2020 to reflect Goettler diary and articles in Rapid City Daily Journal

Notes

(For complete bibliographic entries, please consult the list of works and web pages cited.)

1 Halley’s birth and death dates are taken from his obituary in the Cornell Alumni News (see “Obituaries”). His place of birth and place of death are taken from “Walter Halley Dies in Chicago.” The photo is a detail from a photo of the five Halley brothers that was posted to Find A Grave memorial #31041050 for Samuel Russell Halley.

2 Information on Halley’s family is taken from Wells, “Scotland to the Black Hills of Dakota,” and from other documents available at Ancestry.com.

3 “Walter F. Halley: His Company Helped Build His State.”

4 “Ground School Graduations [for August 25, 1917].”

4a “Chester Pudrith, with American Detachment Royal Flying Corps, Writes from England.” In the newspaper’s publication of the letter, one man’s name is given as “Warren Teoch,” almost certainly a mistranscription of “Warren Leach.”

5 “Local Boy Close to London Air Raid”; Castle, Zeppelin Raids, Gothas and ‘Giants’, page for 29th October 1917.

6 Foss, “Cadets of Italian Detachment Posted Dec 3rd” (in Foss, Papers).

7 From a letter home quoted in “Walter Halley Tells of Experiences in England.”

8 Ibid.; Castle, Zeppelin Raids, Gothas and ‘Giants’, page for 6th December 1917.

9 “Walter Halley Tells of Experiences in England.”

10 Kilduff, “Clayton Knight—Artist & Airman,” p. 199.

11 “Walter Halley tells of Experiences in England.”

12 Knight, quoted in Kilduff, “Clayton Knight—Artist & Airman,” p. 203.

13 Cablegram 823-S, dated March 30, 1918, recommends Halley; 1303-R confirms the appointment.

14 See the entry for Halley on p. 923 of Militia Office, Official National Guard Register for 1927.

15 From a letter home quoted in “With the Boys in Service” (May 16, 1918).

16 Kilduff, “Clayton Knight—Artist & Airman,” p. 206.

17 “With the Boys in Service” (May 16, 1918).

18 Ibid.

19 Ibid.

20 Wiser, Recollections of the DH-4, pp. 125–26.

21 From a letter home reproduced in “With the Boys in Service” (July 19, 1918).

22 Biddle, “Special Orders No. 109.”

23 Goettler, diary entry for July 4, 1918.

24 Goettler, diary entry for July 10, 1918.

25 See “Walter F. Halley: His Company Helped Build His State.”

26 Sloan, Wings of Honor, p. 248.

27 First Day Bombardment Group, pp. 148, 150, 151.

28 “Walter Halley Dies in Chicago”; Wikipedia, “166th Aero Squadron.”

29 “Exodus to S.O.S. Begun.”

30 War Department, Office of the Quartermaster General, Army Transport Service, Lists of Incoming Passengers, 1917 – 1938, Passenger list for the S.S. Suriname.

31 See Ancestry.com, 1920 United States Federal Census, record for Walter F Halley.

32 See “Walter F. Halley: His Company Helped Build His State” and “Black Hills College of Aviation Brochure.”