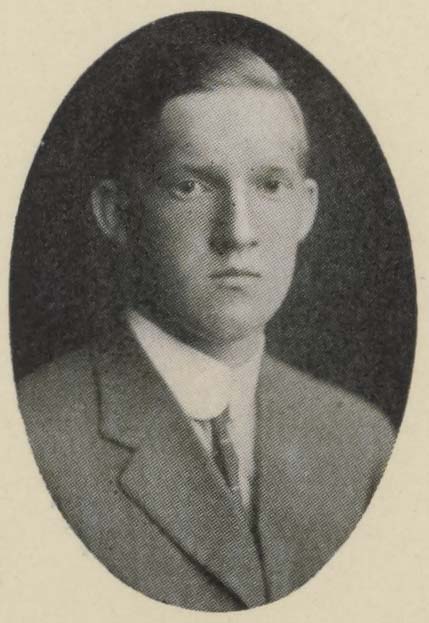

(Columbia, South Carolina, March 7, 1889 – Norwich, Connecticut, November 3, 1932).1

Despite his birthplace, Goodnow was not a South Carolinian, but of New England stock; his ancestor, Thomas Goodenow, sailed from England in 1638 on the Confidence to settle in the Massachusetts Bay Colony.2 Goodnow’s mother was from Baltimore, and her father was from Massachusetts. Goodnow’s father, whose parents had moved from Massachusetts to New York, was born in Brooklyn and studied at Amherst for his undergraduate degree. He pursued advanced work in math and physics in Berlin and at Johns Hopkins before settling in New York.3 Goodnow’s uncle, Frank Johnson Goodnow, also an Amherst graduate, studied law at Columbia and was, from 1914 to 1929, president of Johns Hopkins University.4

Goodnow, like his father and his uncle, studied at Amherst, where he was secretary of the Aero Club and published a paper for the club on “the best methods of generating hydrogen for balloons.”5 After graduating in 1910, he started working at the Fort Orange Paper Company at Castleton-on-Hudson, rising to vice president and general manager.6 In June 1914 he joined the New York National Guard and served in the 1st New York Cavalry, Troop B; as part of the Mexican Punitive Expedition, he served under Pershing and “spent the winter [1916–17] at McAllen, Texas.”7 In June 1917, he enlisted in the Aviation Section of the Signal Corps.8 He attended ground school at Cornell, graduating September 1, 1917. 9

Thirteen of the eighteen men listed as graduates of this ground school class, including Goodnow, chose or were chosen to go to Italy for further training, and were thus among the 150 men of the “Italian” or “second Oxford detachment” who sailed to England on the Carmania. They departed New York on September 18, 1917, and, after a stopover at Halifax to meet up with a convoy, set out across the Atlantic on September 21, 1917, docking at Liverpool on October 2, 1917. Here they learned that they were not to go on to Italy, but would remain in England and attend ground school (again) at the Royal Flying Corps’s No. 2 School of Military Aeronautics at Oxford University.

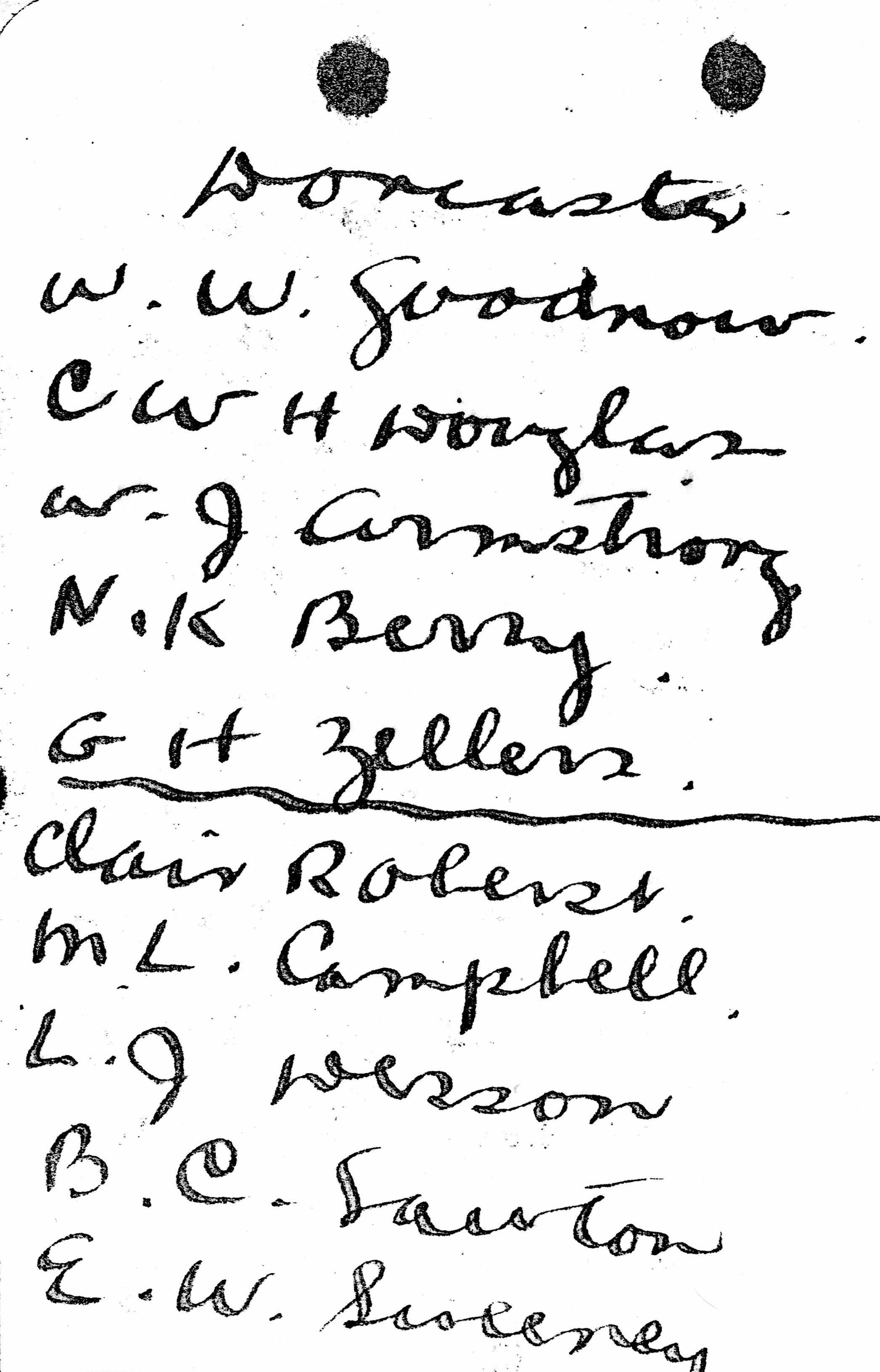

A month later, on November 3, 1917, Goodnow, along with most of the men, departed for Grantham in Lincolnshire to attend machine gun school at Harrowby Camp. In mid-November, fifty of the Grantham men, including Goodnow, were selected to go on to flying schools.10 On November 19, 1917, he and nine others and departed for Doncaster, where Goodnow was posted to No. 41 Training Squadron.11 Towards the end of December, Murton Llewellyn Campbell reported seeing Goodnow at South Carlton; he was among a group “posted to the 45 Pool Squadron.”12 Mentions of him in Joseph Kirkbride Milnor’s diary indicate that Goodnow was still (or again) at South Carlton throughout February and into March 1918. Pershing forwarded the recommendation for Goodnow’s commission as a first lieutenant on March 9, 1918, and the cable confirming the commission came back dated March 22, 1918.13 On the latter day, Milnor, now working for American Aviation HQ in London, wrote in his diary that “Goody came in about 11:00 to say hello. Was very much surprised to see him. He is flying machines from Lincoln to France. Comes back on the boat and then takes another one over.”

On April 3, 1918, Goodnow was posted to the R.A.F., apparently the day prior to his being placed on active service duty.13a On April 14, 1918, he was assigned to No. 203 Squadron R.A.F., a Camel squadron; Goodnow was the only Oxford detachment man to be assigned to 203.14 The squadron was stationed at Liettres, about thirty miles south of Dunkirk, and was engaged in ground support work (low bombing and strafing) in response to the German Lys Offensive, which had begun April 9, 1918, and which was the second and northernmost of the four attacks of the German spring offensive. The R.A.F. typically gave new pilots two to three weeks to orient themselves before sending them over the lines. By early May, when Goodnow would have been ready, the Lys Offensive, having failed in its objectives, had been called off. This meant that 203 returned to offensive patrols and escort missions, and it was presumably mainly this type of work that Goodnow engaged in.15 Leonard Rochford, who wrote about his experiences as a pilot with the squadron in I Chose the Sky, noted that Goodnow took part in an aerial fight on May 15, 1918, near La Bassée.16

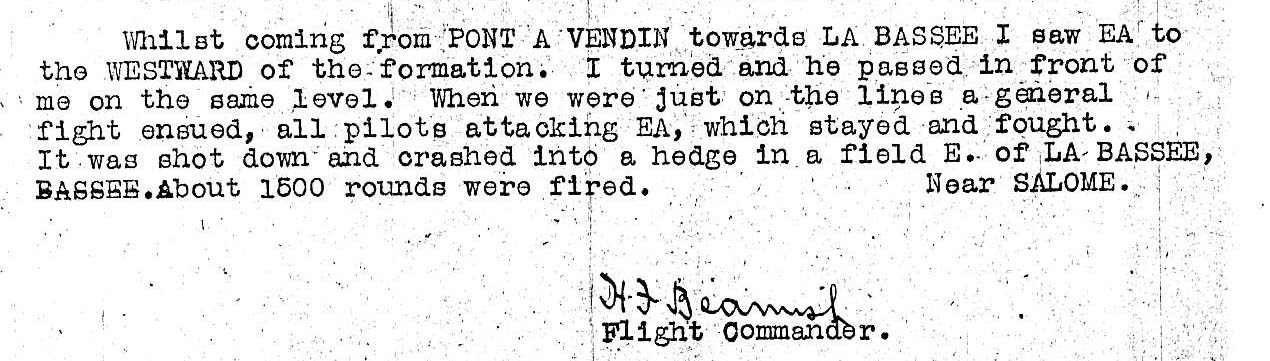

Rochford spent the last three weeks of June in London. “I returned from leave on the last day of June and found that our American pilot Weston Goodnow had left us on posting to the 17th American Aero Squadron. During the short time he was with us he had shot down two E[nemy] A[ircraft] both of which crashed. We were very sorry to lose him.”17 Rochford was probably referring to planes shot down by pilots of No. 203 Squadron on May 15 and May 17, 1918, for which credit was shared in each case among several pilots, including Goodnow. On the 15th, Goodnow was flying Camel B7198 as part of a formation that shot down an LVG C (a two-seater reconnaissance plane) at Salome, east of La Bassée; on the 17th he flew Camel B6212 in a formation that destroyed an Albatros DV (a single-seater scout) south of Merville.17a Goodnow is not credited with these (or any) victories in American tallies.

The U.S. 17th Aero Squadron, whose enlisted man and officers had been dispersed for training shortly after arriving in Europe in January 1918, reassembled at Petite Synthe near Dunkirk on June 20, 1918. Pilots, including Goodnow, as well as Lloyd Andrews Hamilton, Murton Campbell, and Henry Bradley Frost began arriving the next day. Many others from the second Oxford detachment arrived soon thereafter.18 The 17th flew Camels and, along with the 148th, was American in personnel, but stationed on the British Front and under the tactical command of the R.A.F. until late in the war when they were moved south to the American Front. Goodnow, on his arrival, was made flight commander of B flight. On July 1, 1918, when A flight leader Morton Newhall was posted to 148, Goodnow took over as leader of A, with Murton Campbell as his deputy; Leonard Joseph Desson was also assigned to his flight.19

After about three weeks of getting to know their equipment and their territory while working on formation flying (and crossing the lines, despite R.A.F. regulations), the 17th flew their first offensive patrol on July 15, 1918; they began escorting DH.9 bombers into German occupied territory on July 20, 1918.20 Goodnow led his A flight on numerous such missions through July and the beginning of August. All the while, plans were being made for a major raid on a German aerodrome at Varsenare, just west of Bruges, and this, after postponements caused by bad weather, and despite the loss of several pilots, took place on August 13, 1918. Working together with R.A.F. squadrons, the 17thcaused extensive damage. Goodnow “dropped four bombs from about 200 feet on machine shops which were afterwards seen to be burning; shot into a row of machines on the ground, two were already burning; smoke came from third afterwards.”21

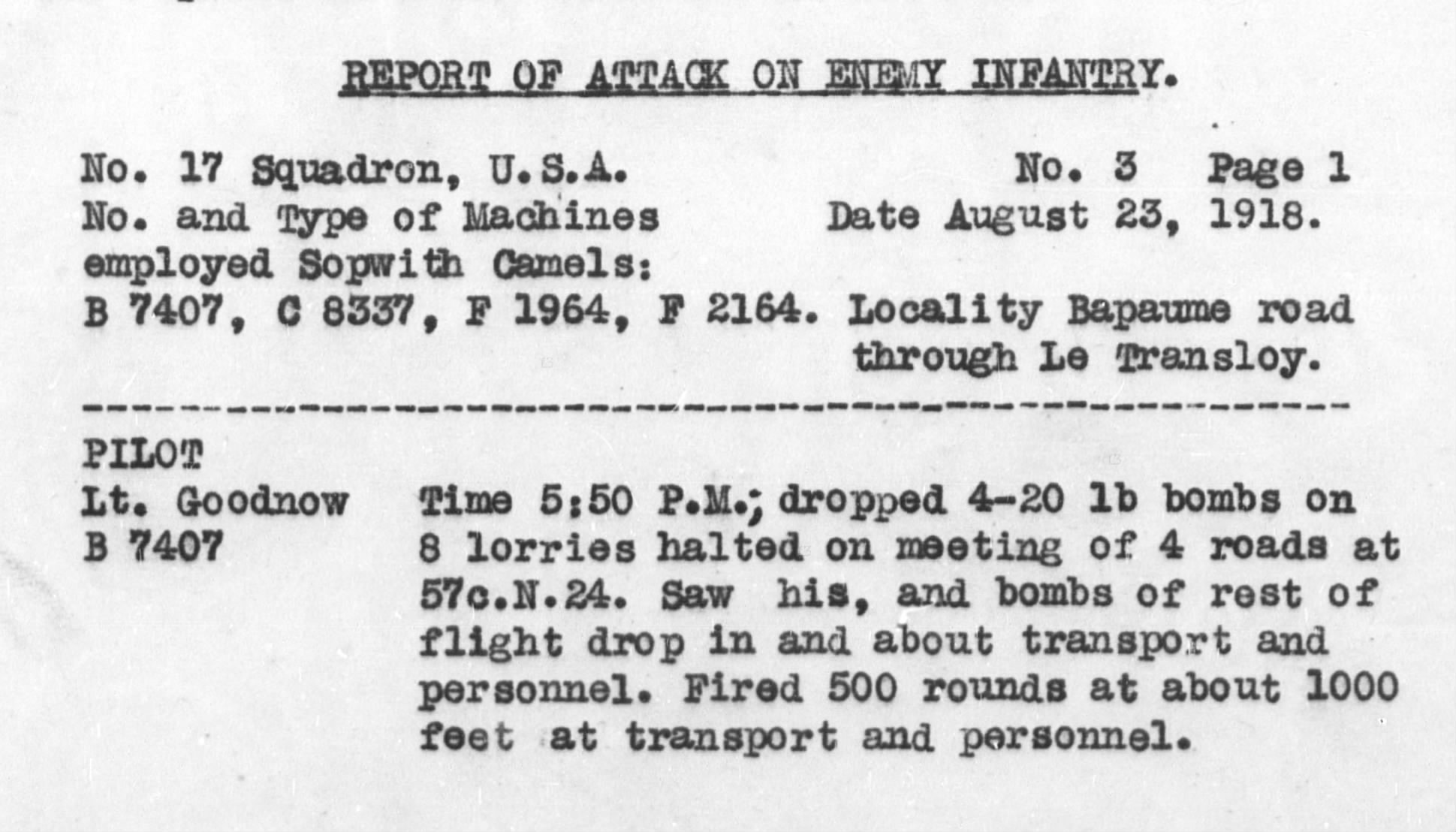

On August 17, 1918, the 17th moved south from Petite Synthe to the (British) Third Army area, specifically, to Auxi-le-Château northwest of Doullens, in preparation for what became known as the Second Battle of Bapaume.22 They were again to escort R.A.F. bombers, but also to do bombing and strafing. They made their first patrol over the lines on August 21, 1918; low bombing and strafing commenced on August 23, 1918.23

Squadron member and historian Frederick Mortimer Clapp explains the rationale for the latter: “It was the nature of the fighting on the ground, while the Hun was going back, that worked so complete a change in our operations. The Air Force of the enemy was largely concentrated in the vicinity of Cambrai, but the congestion on the roads behind his lines gave us an opportunity of doing greater damage to his morale and material by attacks on moving infantry and transport, than we could ever have accomplished by devoting all our attention to his scouts.”24 Goodnow led his flight on a bombing raid on the Bapaume road in the late afternoon of August 23, 1918, and, working with Floyd M. Showalter the next afternoon, dropped bombs and fired rounds on the road from Bapaume to Cambrai.25

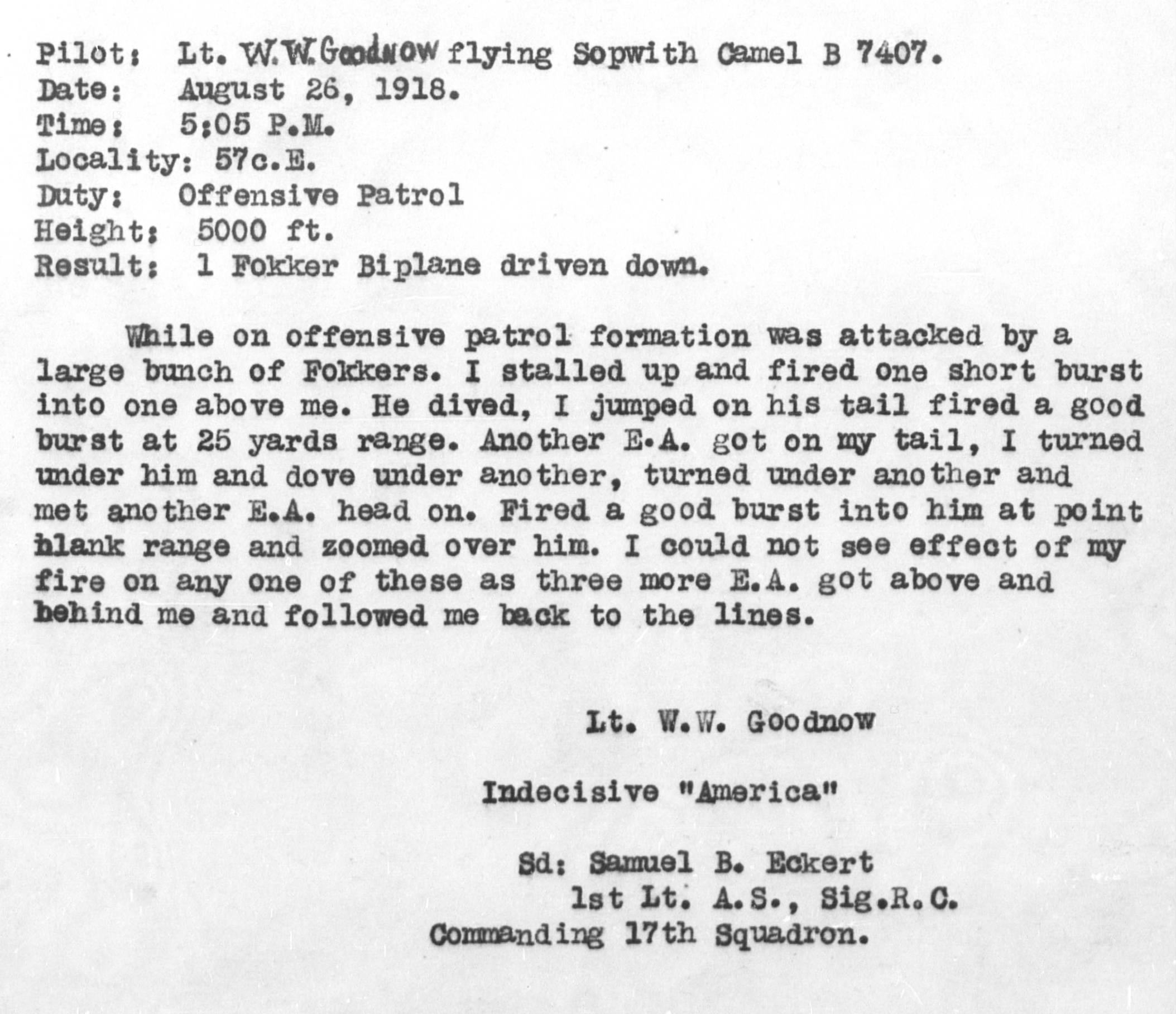

The Germans recognized that their retreating troops needed better air cover and moved experienced squadrons in. On August 26, 1918, when a patrol from the 17th flew to assist pilots of the 148th (who had been ordered out despite severely unfavorable weather), they encountered a swarm of Fokkers over the Bapaume-Cambrai road. Of the nine Camel pilots from the 17th on this mission, three were killed in action; one died that night, and two were captured. Goodnow and Ralph W. Snoke returned, followed, a distant third and last, by Frank Aloysius Dixon. Despite being severely outnumbered, the 17th downed several enemy aircraft; in the melee Goodnow fired on at least two Fokkers, but the results could not be confirmed.26

After losses in the period leading up to and on August 26, 1918, the crippled squadron was given a breather as they tried to figure out how to reorganize at half strength. Goodnow’s A flight had fared somewhat better than B and C, but even this had its downside: there was some grumbling that his “tactic of holding his formation tightly together in fights had paid off in lives preserved, but some thought this cautious approach led to fewer victories.”27 The squadron commander was gradually able to build up strength again: George Augustus Vaughn was brought in from No. 84 Squadron R.A.F., and William Thomas Clements from the 148th. Other new pilots came from the pilots pool.28 During this period Goodnow was able to take his allotted two weeks leave, leaving Snoke to lead A flight.29

A third of the way through September, the 17th Aero was ordered to move once again, this time to Soncamp Aerodrome, about fifteen miles east of Auxi-le-Château. Offensive patrols began September 20, 1918, and it was around this time that Goodnow returned from leave and resumed leadership of his flight.30 Missions were a mix of offensive patrols, reconnaissance, and ground troop support. Clapp describes the squadron’s work: “Dud weather now set in with a vengeance. But the offensive went on. The line changed from day to day. Those were the days of the great battles, on the Third Army Front, for the Canal du Nord, the Hindenburg Line, the Canal de Ll’Escaut, and Cambrai. As the Boche retreated, even through cloud and rain, we bombed his transport and troop concentrations. . . .” “Over and over again, as the battle for Cambrai progressed, our patrols met and made sallies at a large formation of blue-tailed Fokkers”; these disappeared on September 24, 1918, as suddenly and mysteriously as they had appeared.31 Goodnow participated in numerous bombing raids, sometimes twice a day, in late September and early October, the targets moving farther to the east as General Sir Julian Byng’s drive to take Cambrai progressed and succeeded.32 Goodnow participated in the squadron’s final mission, an offensive patrol on October 28, 1918.33

In fact, the targets were moving almost beyond flying range from Soncamp, and the squadron began to prepare to relocate farther east. But then word was received that the 17th was instead to move south to the American sector, and on November 1, 1918, they began the long, slow train journey, arriving, finally, near Toul on November 4, 1918.34 After the mud and tents of Soncamp, the accommodations at Toul were a welcome change.

Clements wrote in his diary on November 5, 1918: “of all the barracks I have had the pleasure of being in since the war began these are the best. The buildings are all stone with steam heat and also coal stoves. . . . Why the Huns haven’t blown the whole thing up long ago I can’t imagine. The line is about 14 miles away—even in shelling distance. A double room with Goodnow and we have things fixed up pretty nice.” Six days later, plans for the men of the 17th to fly with the A.E.F. disappeared in the jubilation of the armistice.

About November 25, 1918, Goodnow, Vaughn and Desson, “three fellows who had been at the front the longest,” were ordered to report to Issoudun; “the orders did not say so, but we understood that we were to be sent home as soon as possible.”35 They were able to enjoy a brief stay in Paris en route, but once arrived at Issoudun, it was “hurry up and wait” until February 1919. Goodnow, along with Dixon, was in a group of officers who sailed from Brest on the Ortega on February 7, 1919, arriving at New York on February 19, 1919.36 He was honorably discharged on February 24, 1919.37

Goodnow resumed his work at the Fort Orange Paper Company and soon acquired another similar factory; he later helped manage the American Thermos Bottle Company in West Virginia.38

mrsmcq July 26, 2017; updated August 21, 2020, to reflect Milnor’s diary

Notes

(For complete bibliographic entries, please consult the list of works and web pages cited.)

1 For his place and date of birth, see Ancestry.com, New York, Abstracts of World War I Military Service, 1917-1919, record for Weston Whitney Goodnow. For his place and date of death, see the entry for Goodnow on p. 502 of Newlin, Young, and Fletcher, eds., Biographical Record of the Graduates and Non-graduates: Centennial Edition 1821-1921. Revised Edition. The photo is taken from Rochford’s I Chose the Sky, with kind permission of Grub Street.

2 See entry for Goodenow on p. 215 of Whittemore, Genealogical Guide to the Early Settlers of America; Crane, Historic Homes and Institutions and Genealogical and Personal Memoirs of Worcester County, Massachusetts, v. 1, pp. 58 and 60; and documents available on Ancestry.com.

3 See the entry for Henry Root Goodnow on pp. 115-16 of Montague, Biographical Record of the Alumni and Non-graduates of Amherst College (Classes ’72-’96). On Goodnow’s paternal grandparents, see p. 8 of the “Proceedings at the Sixth Annual Meeting,” in New England Society in the City of Brooklyn, Proceedings . . .; on his maternal grandfather, see “Ableben des Hrn. Milton Whitney.”

4 Wikipedia, “Franklin Johnson Goodnow.”

5 Todd, “Amherst Aero Club.”

6 See entry for Goodnow on p. 502 of Newlin et al., Biographical Record, cited above.

7 “The Classes,” p. 215.

8 Ancestry.com, New York, New York Guard Service Cards, 1906-1918, 1940-1948, entry for Weston Whitney Goodnow.

9 “Ground School Graduations [for September 1, 1917].”

10 Hooper, Somewhere in France, letter of November 14, 1917.

11 See Foss, Diary, entry for November 15, 1917, and Murton Campbell, Diary, November 19, 1917.

12 Murton Campbell, diary entry for December 28, 1917.

13 Cablegrams 702-S and 967-R.

13a Munsell, “Air Service History,” p. 188 (3); see also Goodnow’s casualty form (“Lieut. Weston Wesley Goodnow U.S.A.S.”). McAndrew, “Special Orders No. 205” give the date for his active service duty.

14 “Lieut. Weston Wesley Goodnow U.S.A.S.” Munsell, “Air Service History,” p. 188 (3), gives the date of his posting to the squadron as April 16, 1918. Reed and Roland, Camel Drivers, p. 31, put him with 209, but this is probably a careless reading of text on p. 16 of Clapp, A History of the 17th Aero Squadron.

15 On 203’s activities during this period, see Rochford, I Chose the Sky, Ch. 10.

16 Rochford, I Chose the Sky, Ch. 10.

17 Rochford, I Chose the Sky, Ch. 10, penultimate paragraph.

17a See the entry for Harold Beamish on p. 67 of Shores, Franks, and Guest, Above the Trenches.

18 Clapp, A History of the 17th Aero Squadron, pp. 8–13 and 155.

19 Skelton, “Frank A. Dixon and the 17th Aero Sqdn.,” pp. 157-58.

20 See Clapp, A History of the 17th Aero Squadron, p. 24; Reed and Roland, Camel Drivers, pp. 35 and 40.

21 Clapp, A History of the 17th Aero Squadron, pp. 97-98; see also Reed and Roland, Camel Drivers, p. 59, and Ch. 5 passim on the raid generally.

22 See Murton Campbell, diary entry for August 17, 1918, for the date of the move, which is unclear from other sources (Clapp, A History of the 17th Aero Squadron, p. 37; Reed and Roland, Camel Drivers, pp. 64-65; Jones, The War in the Air, p. 469).

23 Clapp, A History of the 17th Aero Squadron, p. 37.

24 Clapp, A History of the 17th Aero Squadron, p. 38.

25 Clapp, A History of the 17th Aero Squadron, pp. 100-1 and 103-4.

26 Reed and Roland, Camel Drivers, pp. 80-83, offer a vivid reconstruction of the events of this encounter. See also, Clapp, A History of the 17th Aero Squadron, pp. 74-77, where the combat reports are reproduced, and 40-41 for a narrative account.

27 Reed and Roland, Camel Drivers, p. 86.

28 Reed and Roland, Camel Drivers, p. 87.

29 Reed and Roland, Camel Drivers, p. 89.

30 Reed and Roland, Camel Drivers, p. 98.

31 Clapp, A History of the 17th Aero Squadron, pp. 48, 49, and 50.

32 Clapp, A History of the 17th Aero Squadron, pp. 106-45.

33 Reed and Roland, Camel Drivers, pp. 115-16.

34 Read and Roland, Camel Drivers, p. 115 on the planned move east; p. 119 on the journey to Toul; Clements, “World War Diary of W. T. Clements 1917-1918,” entry for November 4, 1918, for their arrival.

35 Clements, “World War Diary of W. T. Clements 1917-1918,” combined entry for Nov. 13-25; Vaughn, War Flying in France, letter of November 28, 1918.

36 War Department, Office of the Quartermaster General, Army Transport Service, Lists of Incoming Passengers, 1917 – 1938, Passenger list for officers on the S.S. Ortega.

37 Ancestry.com, New York, Abstracts of World War I Military Service, 1917-1919, record for Weston Whitney Goodnow.

38 See entry for Goodnow on p. 502 of Newlin et al., Biographical Record, cited above.