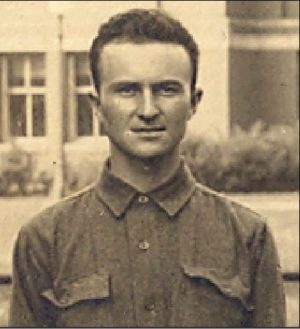

(Gloucester Courthouse, Virginia, February 20, 1896 – West Point, Virginia, October 12, 1952).1

Oxford and Grantham ✯ Scampton & Waddington ✯ From Marske to France and the U.S. 148th Aero ✯ With the U.S. 17th Aero Squadron ✯ Leaving the R.A.F., heading home

Clements’s family had lived in the Tidewater Virginia county of Gloucester for at least five generations when William Thomas was born at the county seat, Gloucester Courthouse.2 His grandfather had served as a musician in the 26th Virginia Infantry during the Civil War before going into business as a coachmaker.3 Clements’s father went into the related business of blacksmithing. The family relocated from Gloucester Courthouse to West Point not long after Clements was born.4 After high school, Clements worked for about a year at the State Bank of West Point. He then attended Richmond College before enrolling in the Wharton School at the University of Pennsylvania. While studying finance he also worked at the Kensington National Bank of Philadelphia.5

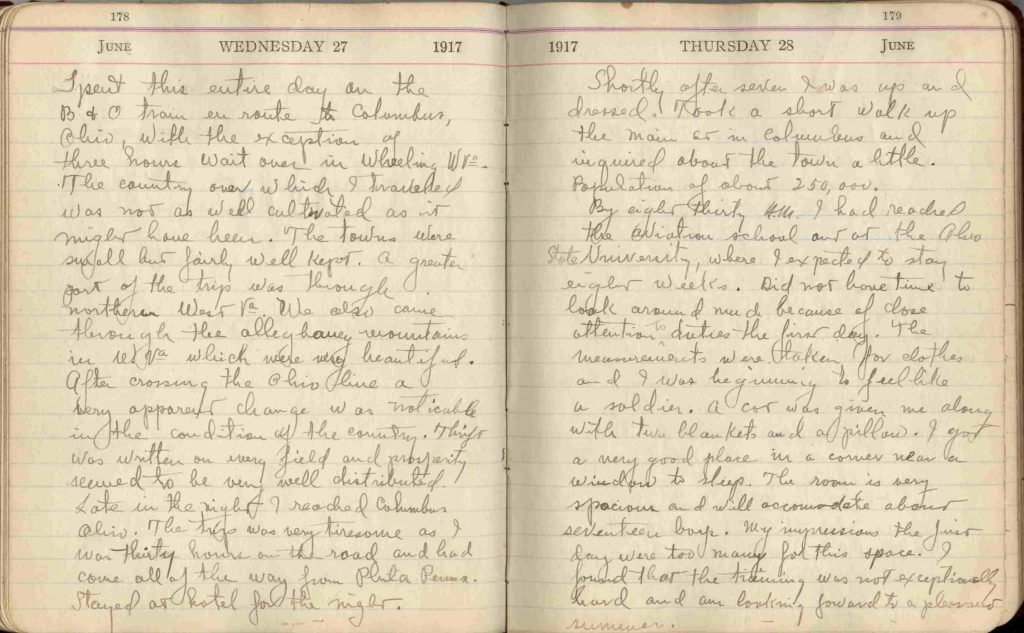

Clements enlisted on May 28, 1917; a month later he arrived at Columbus, Ohio, where he was enrolled in ground school at Ohio State University’s School of Military Aeronautics.6

Towards the end of his course there, on August 17, 1917, as Clements wrote in his diary: “The captain announced . . . that men would not be sent to France any more, but to Italy. He asked for volunteers, and I was crazy enough to volunteer.” Clements’s class graduated August 25, 1917, and three days later he and many of his classmates were on their way to Mineola, New York.7 Three weeks later, as one of the 150 men of the “Italian” or “Second Oxford Detachment,” Clements sailed to England on the Carmania, departing New York for Halifax on September 18, 1917, and departing Halifax on September 21, 1917.

Oxford and Grantham

The Carmania docked at Liverpool on October 2, 1917. “There was a big disappointment today. We came straight to Oxford instead of going to Italy and understand that we have to do our ground school work over again. The boys are making an awful yell about it, and I am discouraged myself.”8 Clements was assigned to a room in Christ Church as part of Elliott White Springs’s group of cadets (as they were now called): “Our rooms are fair, but there is very little coal and I can’t see how we are going to get through six weeks here without wood or coal to keep our room warm.”9 Like most of the cadets, Clements was invited to tea at the home of Sir William and Lady Osler (“Lady Osler seems to be extremely courteous to the Americans”).

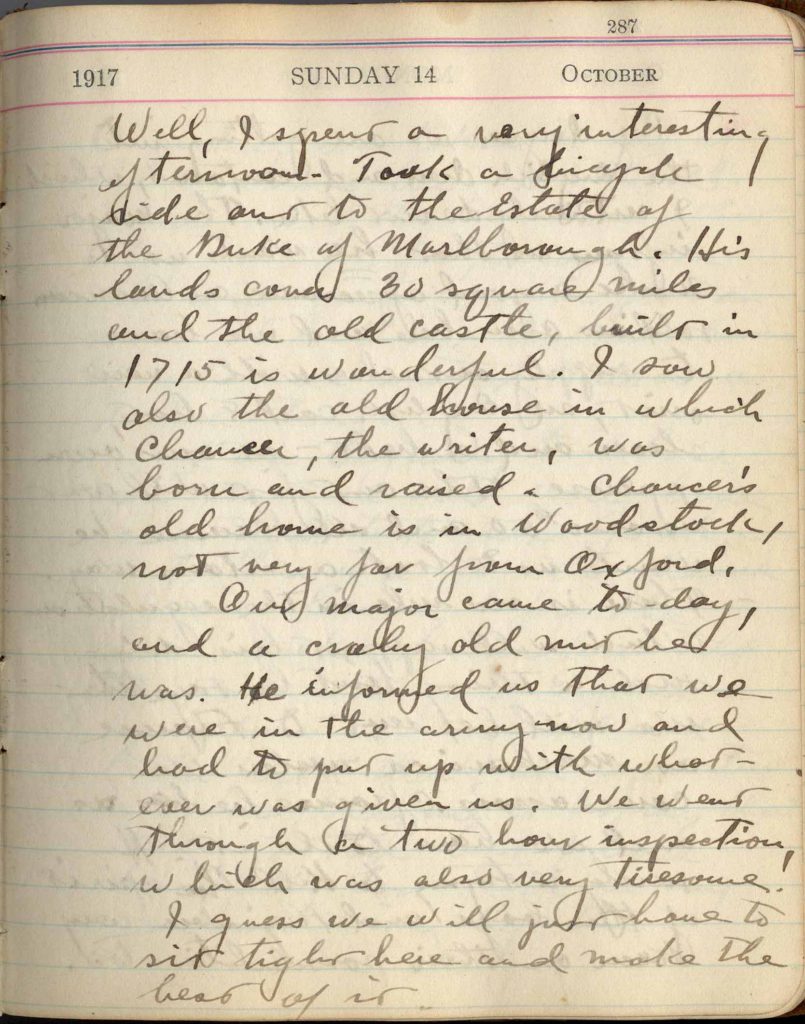

With Hugh Douglas Stier, Arthur Paul Supplee, and George Herbert Zellers, with whom he had been at ground school, he explored the country around Oxford by bicycle, despite rain.10 Like other cadets, he was not happy when American Major Gordon Robinson (“a craby [sic] old nut”) who inspected them on October 14, 1917, insisted they purchase new uniforms at their own expense: “There is no rule in the regulations which will support his doing such a thing but he says that we will be sent to France as mechanics unless we come across.”11

At the beginning of November it “was announced definitely that 130 of us would leave Saturday. To our sorrow though we hear that it is to take up a machine gun course instead of starting our flying.”12 On November 3, 1917, Clements and most of the men departed Oxford for Harrowby Camp near Grantham in Lincolnshire. “Our arrival was rather spectacular as we had a band down to meet us and escort us up to the camp. Our real life as an officer has at last begun. We were transferred with the standing of 1st lieutenants and are surely being treated as such”; among the perquisites now were batmen, one for every eight men.13 The men began training on Vickers guns. On November 13, 1917, word came that fifty of the men at Grantham would shortly be assigned to flying schools, but once again Clements’s luck was out, and he remained at Grantham. The program of study and practice now moved on to Lewis machine guns. Clements and Supplee enjoyed a break from this when they made a weekend outing to Notthingham.14 Finally, the day after Thanksgiving, a “letter came from London this noon saying that all of us would be posted to different R.F.C schools Monday morning. We hate to be split up, but we certainly are glad that at last we will get some flying.”15 The next day: “We were actually paid today. Capt. Swan [sic] came down from London with a suitcase full of money and gave us all a little over £20 a piece.” (John Warren Swann had been supply officer on the Carmania during the voyage to England and became the disbursement officer at the American Air Service headquarters in London.)

Flight training at Scampton, Waddington, and, again, Scampton

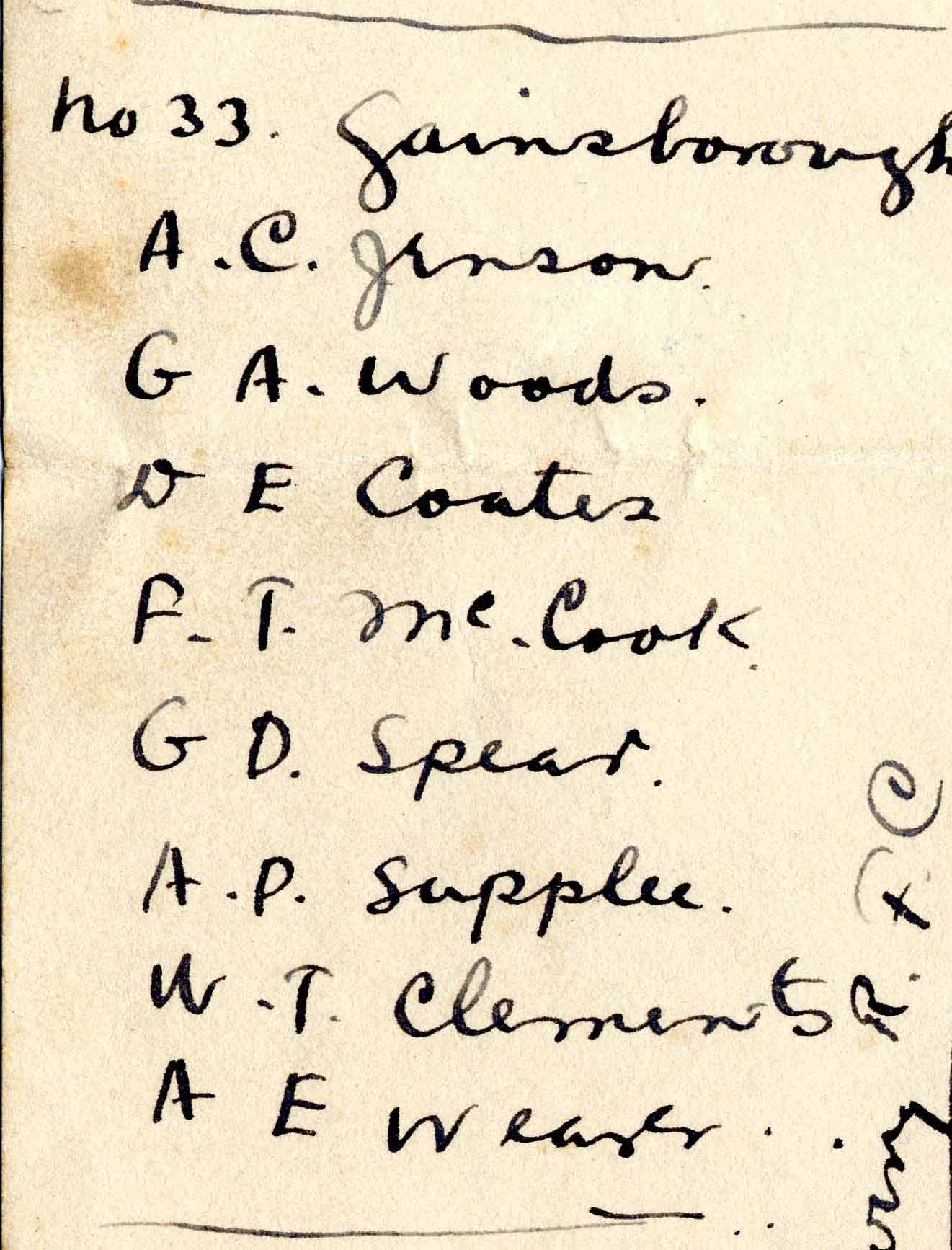

On December 3, 1917, Clements left for Gainsborough, about thirty-five miles north of Grantham, to train with No. 33 Home Defense Squadron.16 That day he wrote in his diary: “Well, they didn’t know what to do with us after we got up here. . . . We were sent out here to Scampton.” A flight from No. 33 was located at Scampton, about ten miles southeast of Gainsborough, flying F.E.2b’s and F.E.2d’s.16a Clements roomed with Supplee. The day after arriving at Scampton, Clements wrote: “AT LAST!! I have been in the air. Went up about 2,300 feet today with one of the men here in a pusher.”

At the end of January 1918 Clements, along with Supplee and two other men, was transferred to Waddington, home to several training squadrons, and was assigned after a few days to No. 47, a “Rumpety” squadron (the Maurice Farman Shorthorn, commonly known as a “Rumpty,” or in Clements’s case, a “Rumpety,” was a pusher biplane much used in training at this time). Despite bad weather, Clements had completed five hours of solo flying on February 14, 1918, noting “they have the idea that I am pretty keen on flying so I hope they send me to a scout squad.” But he remained at No. 47 and started training on a DH.6, “and I must content myself with D.H.4 as a goal.”17 However, on February 22, 1918, he learned that he was to return to Scampton to train on scouts and departed the next day. He had soon looped an Avro, flown solo, and experienced his first (minor) crash.

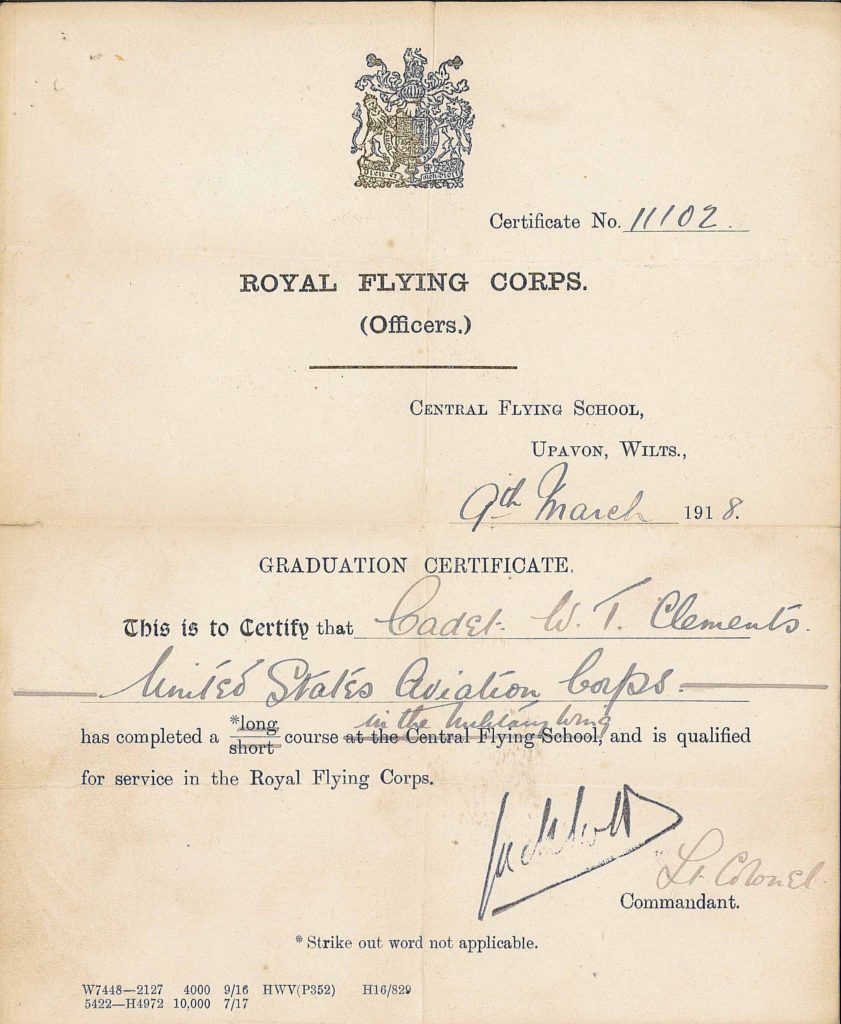

On March 9, 1918, he moved on to flying a Sopwith Pup; by the end of the day his total solo hours on Avros and Pups was fourteen hours and twenty-five minutes. He had “graduated by both R.F.C. qualifications and ours,” and was recommended for a commission.18

The next day Clements enjoyed local hospitality extended to flyers, taking tea at nearby Hackthorn Hall before embarking on a week’s leave, presumably graduation leave, in London. On March 17, 1918, he was back in harness, flying Avros and Sopwith Pups; of the latter he wrote: “I am trying to get in as much time as possible on this machine as my day is coming on Camels and they are known to be tricky.”19 And, indeed, a few days later, on March 23, 1918, he took up a Camel for the first time: “I can see France now just as plain as daylight.” Nonetheless, he still had reservations about flying Camels: “This ‘Camel’ machine is the only one yet that I am not particularly anxious to fly. The little devils are fast as lightning and tricky as a cat. . . . Flew about an hour in them today, and am glad I got off without breaking my neck. They have me scared properly.”20

Clements’s instructor, the otherwise unidentified Major Pollard, asked him to do some ferrying (within England as it turned out, although Clements initially thought it meant going to France), which gave him more extensive experience flying Camels; shortly after his second ferrying job, he learned that his commission as a first lieutenant had come through.21

Clements had clearly impressed his R.F.C. superiors. Soon after he completed his ferrying duties, he was asked whether he would be interested in serving as an instructor; the idea was initially quashed as against American regulations.22 However, the idea persisted, and after Clements had completed another tricky assignment, Major Pollard “told me that he would like for me to instruct, and start at once in the 11th sq. This is against American orders, but instruct I will”—this enthusiasm, despite recent fatal Camel crashes.23 Clements witnessed the accident that killed Stanley Huguenin, Nathan Krantinann, and B. J. Siefert on April 3, 1918: “About the worst crash that I have ever seen happened here today. One of our American pilots [Huguenin] was thrown out of a camel about 200 ft. up and the machine fell on a Dolphin which was being tested at the time, killing two American mechanics.” (There are photos of the crash in Clements’s album.) A little way into his time as an instructor, Clements remarked: “This seems to be an unlucky station for Camel pilots.”24 But he expressed regret towards the end of the month when he learned that the “station is washing out Camels, much to my sorrow, and are going to use Dolphins only. So many men have been killed here on Camels that the entire crowd had the ‘wind up’ properly about the machine. I was darn glad to get through my time here without accidents, but the machine is a little wonder to fly.”25 (Later diary entries indicate that, in fact, instruction on Camels continued.) On the last day of April Clements was promoted to “Commanding Officer of D Flight 11th [Training] Squadron,” and he continued serving as an instructor through the end of May.

From Marske to France and the U.S. 148th Aero

In early June Clements was ordered to No. 2 Fighting School at Marske, where he arrived on June 15, 1918, having spent some leave time in Brighton and Edinburgh. He was not happy with the accommodations or the course at Marske, so it was welcome news when on June 20, 1918, “orders came through for five American pilots (Camels).” Clements, along with his flying student and friend William H. Shearman, Jr., was among those selected and left London for France on June 23, 1918. “This is rather phenomenal, starting this diary one year ago tomorrow and reaching France exactly one year from the day I entered the army. Everything is unusual now so we must expect anything.” He was disappointed on arrival at the Rang-du-Fliers camp to find that it was not a squadron but a pilots pool. On June 29, 1918, Clements wrote in his diary that “Sherman [sic] was posted today to No. 17 American sq. I hated to see him go as we had become quite good friends. We were trying to get to the same sq. but it was no use.” Three days later: “[Oscar] Mandel, Galbreth [sic; sc. Thomas M. Galbreath], some other Americans and myself were posted today to No. 148th American squadron. . . . We were all pleased to hear it and hope to get away as soon as possible.”

On July 3, 1918, Clements finally arrived at the 148th Aero Squadron, to be followed the next day by fellow second Oxford detachment members Marvin Kent Curtis, Lynn Humphrey Forster, John Hurtman Fulford, and Walter Burnside Knox. Springs, who had been transferred from No. 85 Squadron R.A.F., and Field Eugene Kindley, who had been with No. 65 R.A.F., had arrived at the 148th a few days previously.26 The 148th, stationed at Cappelle Airdrome near Dunkirk, was, along with the 17th, American in personnel, but stationed on the British Front and under the tactical command of the R.A.F. until very late in the war when they moved south to the American Front.

Clements had his first unofficial “look at the lines” on July 7, 1918. The morning of July 10, 1918, he went on his first regular patrol, flying with B flight, temporarily commanded by Harry Jenkinson, Jr. (Springs, the nominal leader, was recovering from a crash), and the next day Clements had his first encounter with anti-aircraft fire once the patrol reached Bruges. Flights over the lines continued, weather permitting, sometimes for the purpose of escorting bombers from No. 211 Squadron R.A.F. By August 1, 1918, Springs was able to take command of his flight again, and Clements ceased being deputy flight leader.27

On August 11, 1918, the 148th moved from the relatively quiet Nieuport-Ypres Front south to Allonville, near Amiens, and was attached to the British Fourth Army, operating on the front from Albert to Roye. On this much more active front the danger was less the anti-aircraft fire than the many enemy planes, and Clements experienced his first air combat.

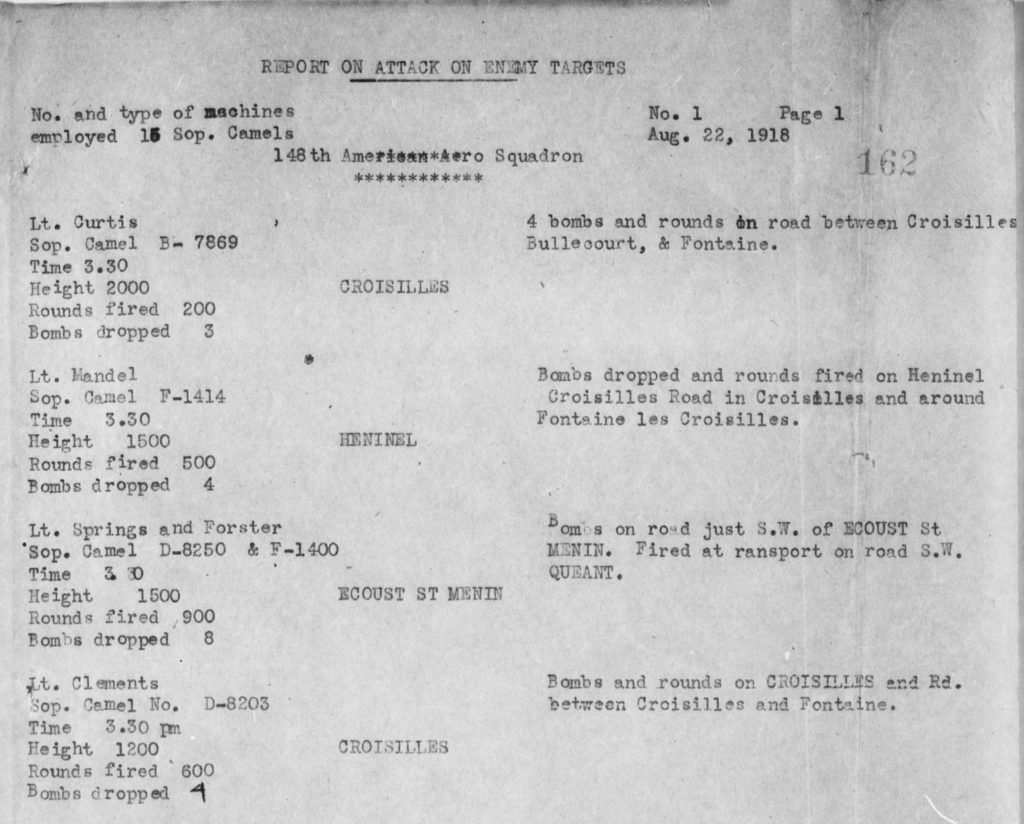

A week later, the squadron moved once again, north to Resmaisnil, in the vicinity of Doullens, and was attached to the British Third Army, commanded by General Sir Julian Byng, which was preparing for its drive towards Cambrai. The threat of having to do dangerous low-ground strafing and bombing hung over the squadron, but initially Clements did regular patrols with Springs and B flight. However, on August 23, 1918, “our [bad] dreams came true. We had two patrols of low straffing,” and low strafing continued over the next days.

On August 26, 1918, despite bad weather and strong east winds, and apparently unaware that the Germans had moved in air squadrons to support their troop withdrawal, “the colonel of the wing took it upon himself to send us out on another ground straffing expedition.”28 The 17th Aero flew out to support the 148th and were attacked by a large number of enemy aircraft; six men from the 17th did not return. Clements’s account of the disastrous encounter reads in part:

One of our boys, Seibold, has not returned, and as I saw eight Fokkers get on a camel, I am afraid Seibold went down. 17th went after the 8 Fokkers and were jumped on by 15 more, making a total of 23 Fokkers and 11 camels. There was a strong wind blowing over Hunland and the fight worked east, of course. Several machines went down. Six of 17th have not returned and the worst is feared for them. The Flight commander made a bad mistake by following the first bunch of Huns over, and the other Huns shot them up.

Clements himself had to turn back after getting very close to an enemy plane when “both guns stopped. I was going straight down on him and had to pull out to keep from having a mid-air crash. Of course, my guns put me out of the scrap. What I told the gunnery men should not be said in the best regulated families.”29

With the U.S. 17th Aero Squadron

Seibold had been in line for leave; now Clements’s leave was moved up, and in the course of the day (August 27, 1918) he was told he could depart the next day.

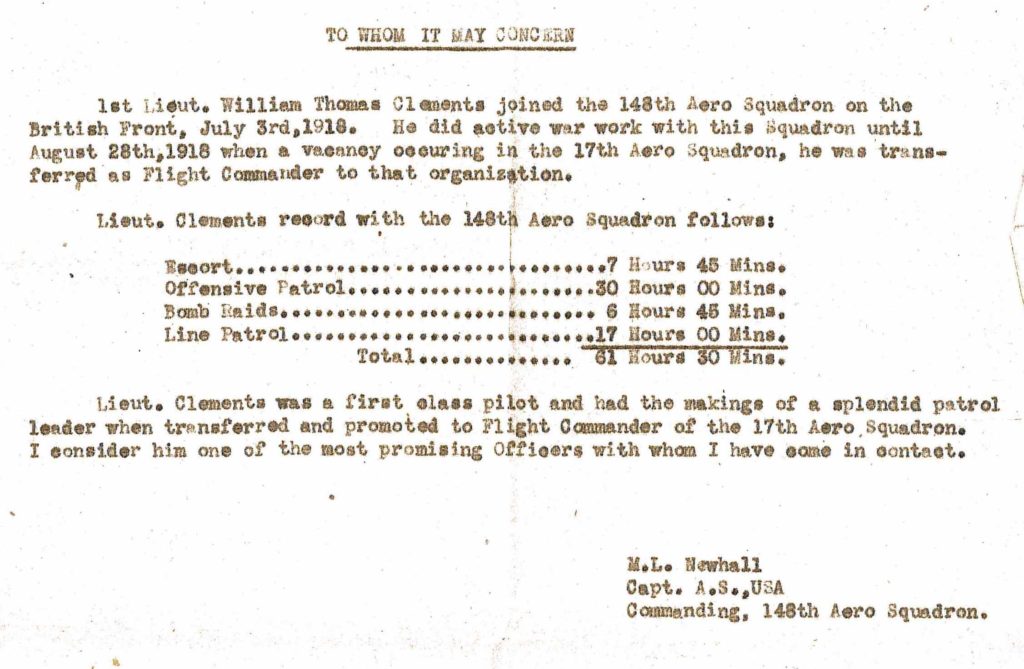

That evening, however, he was told that instead of going on leave, he was to be transferred to the 17th Aero Squadron: “They have lost quite a lot of men lately and sent out a call.” Moreover, he was to take over C flight, whose leader, his fellow second Oxford detachment member Lloyd Andrews Hamilton, had been killed August 24, 1918. “I did not know whether to be sorry or glad. The idea of leaving 148th was distasteful but was offset by the promotion.”30 Clements arrived at his new squadron, stationed at Auxi-le-Château, also in the vicinity of Doullens and also attached to General Byng’s Third Army, on August 28, 1918, and soon found that “I am falling into this F.C.’s job more or less naturally because I officiated in that capacity at Scampton.”31

On September 2, 1918, Clements wrote that “I was cursing my luck for having to leave 148th sq. and come to 17th. That change, coming when it did, saved my life. I came over only about four days ago, and yesterday the old flight I was in, with the exception of one man, was completely wiped out. Springs, the Flight Commander, was the only one to return out of a flight of four. Mandel, Forster, [Johnson D.] Kenyon, were shot down, and I probably would have been also had I remained with 148th three days longer.”

On September 5, 1918: “We started balloon line patrols. . . . On our patrol this morning we saw plenty activity. Huns were chasing our fellows back about as fast as they would go over the line. The Huns are on the offensive around here now and we can’t exactly make them out. It must be a circus of some kind because they have all kinds of machines mixed up among them. Nearly every squadron on the front now has lost a bunch of men on account of these new Huns coming up here. Our line is steadily advancing beyond Bapaume and towards Cambrai. Here’s hoping they soon take Cambrai.”

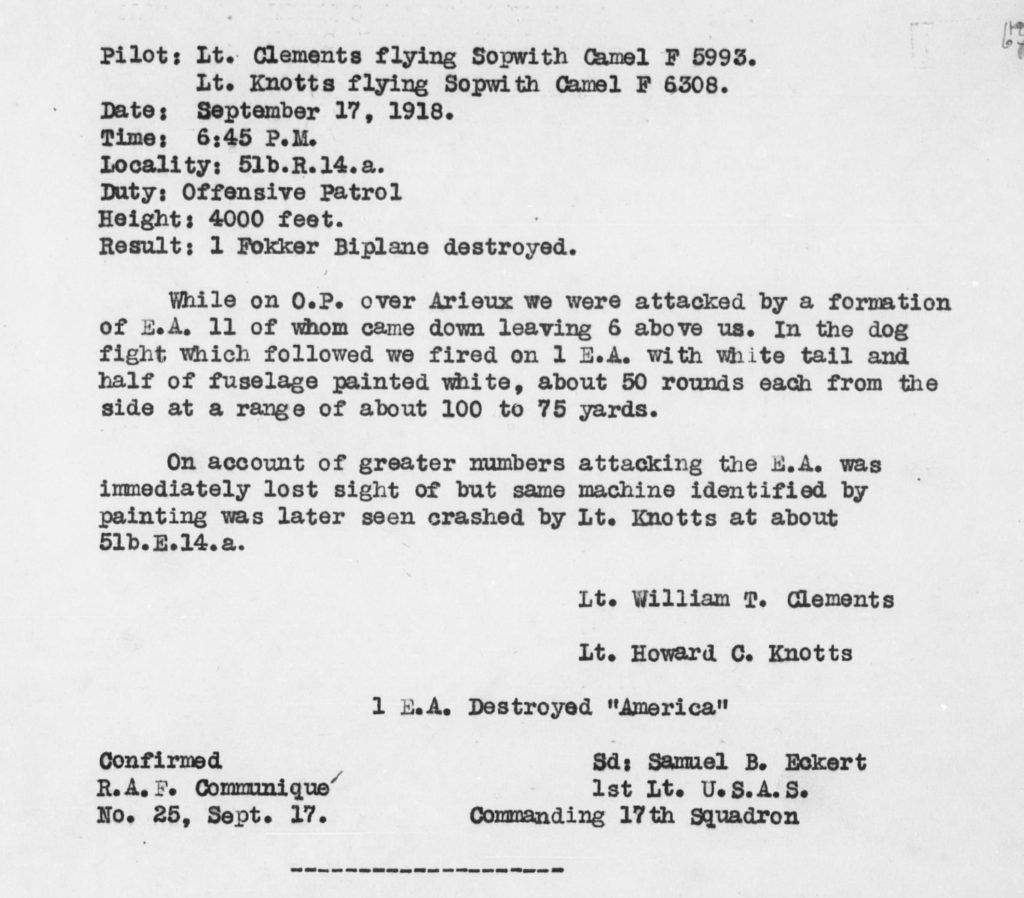

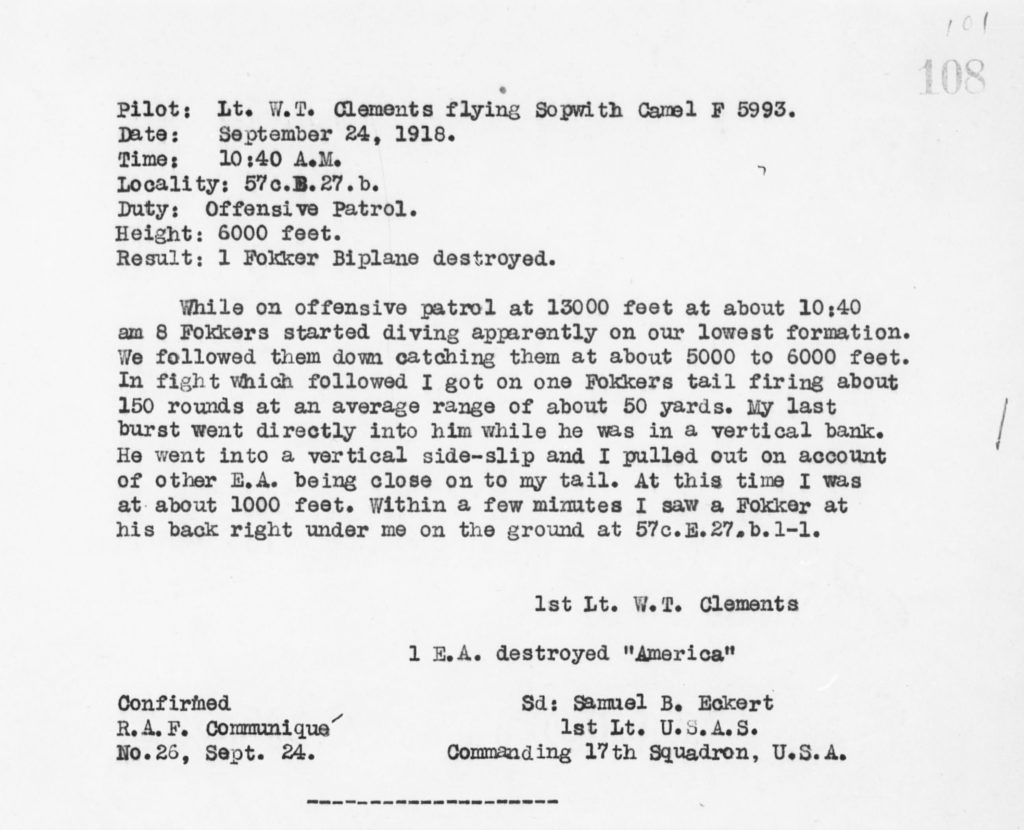

On September 9, 1918, he wrote that “instead of regular offensive patrols we do wireless interception. That means that one flight at the time goes up to an advanced landing ground outside of Bapaume and awaits wireless calls for attack on two-seaters coming down the lines.” But bad weather prevented their carrying out this kind of work until September 13, 1918, when “I had the pleasure of leading my new flight on Huns. We caught two about on the lines. [Howard] Knotts put in for one and if the other got back he was lucky.” Four days later, on September 17, 1918, returning from patrol, Clements’s flight was involved in a scrap with eleven enemy planes, and he “helped a Fokker down to his aerial grave”; this was the first of his two confirmed victories.

The 17th Aero moved to Soncamp aerodrome, about fifteen miles east of Auxi-le-Château and still in the vicinity of Doullens, on September 20, 1918.32 “I have packing down to a science and can move at a minute’s notice.”33 During this period, according to squadron member and historian, Frederick Mortimer Clapp, “over and over again, as the battle for Cambrai progressed, our patrols met and made sallies at a large formation of blue-tailed Fokkers.”33a On September 22, 1917, the 17th engaged with them and shot down four of the over thirty enemy airplanes; Clements remarks “I got in some good shots at some of the Fokkers.” Two days later, there was a similar scrap:

Each day we think we have seen the worst fight. The climax was reached this morning when the worst yet happened. Some people think that Huns can’t scrap. Well, I thought they couldn’t either until I ran into the best scrapper this morning I have ever seen, including allied and Hun. Our regular patrol was around 10 o’clock and I was on top as the protecting flight when we met a bunch of Huns. They went down and I went down after them. It was a darn good crowd and you had to fight. I fought one bird from 6,000 feet to the ground. I used every possible maneuver I have ever learned but he could do them all as well and better than I could. Around and around we went, until I was absolutely on the carpet. I had just gotten a good burst into him when another Hun got on my tail. I don’t think my burst went wild that time because when I had a chance to look again there was a Fokker on his back right beneath me. I claimed him, of course. All of our boys returned and four of the Huns did not. . . . My machine was all shot to pieces. Explosives had hit all round me. I was darn lucky to get out alive. Knotts shot one Hun off my tail and probably saved my life.34

Clements’s effort on September 22, 1918, was designated “indecisive,” but his claim for the Fokker on the 24th was confirmed.35

On September 25, 1918, Clements noted that the “circus seems to have parted these parts. We don’t see anything of them now. I suppose they are taking a rest.” On the 27th: “The big bunch of Fokkers seem to have disappeared all of a sudden, and we have not seen anything of them for days now.” Clements put in four days of “low work,” dropping bombs in the vicinity of Cambrai on September 27, 28, and 29 and October 1, 1918.36 Then he had leave, which he spent in London, staying there until about the 20th and palling around with Supplee. On rejoining his squadron he found that Knotts from his flight had been taken prisoner, and that the “squadron has dwindled to 12 pilots and there doesn’t seem to be much of a chance of getting any more. Both 148 and 17 are going to pieces now and will take a lot of rebuilding.”37

Leaving the R.A.F., heading home

On October 28, 1918, the “news has come through officially that we are to move south” to the American sector. On November 1, 1918, they began the journey, by slow train, arriving, finally, near Toul on November 4, 1918. Clements was pleased with the quarters he was to share with fellow second Oxford detachment member Weston Whitney Goodnow, and with the news that they were to fly Spads. On November 7, 1918, he writes with awareness that the end of the war is imminent, and with jubilation on the 11th. Commemorative photos were taken of squadrons at Toul.

Clements wrote in his diary on November 26, 1918, that “Capt. Eckert has recommended me for the D.S.C. . . . and a captaincy. . . . I was offered command of a squadron last night but refused. I thought the thing over pretty thoroughly and decided that so long as I was getting out of the service anyway it would be best for me to get home just as soon as possible.”38 Clements’s exceptional ability was also noted higher up the chain of command. In a memo dated December 12, 1918, Frank Purdy Lahm, Chief of the U.S. Second Army Air Service, of which the 17th was now part, singled him out, along with Jesse Campbell, as among “the best types of pilots.”38a

Clements was able to sail home on March 7, 1919, leaving from St. Nazaire on the U.S.S. Dakotan; his shipmates included the C.O. of the 17th Aero Squadron, Samuel B. Eckert and Jesse Frank Campbell.39 In November Clements married his sweetheart, Edulia Price, who had given him his diary when he started ground school and had waited for him through the war.40

At the end of the typescript of Clements’s diary he has included a page that describes the staffing of the 17th and 148th squadrons, followed by some statistics. He remarks that “both squadrons had over 100% replacements. There were only about 3 pilots in 148th and 3 in 17th who lasted from the beginning through to the Armistice. I was told that 96 of our original detachment of 200 were either killed in training or on the front. A good many others were permanently injured. . . . Considerable loss of life could have been prevented by the use of parachutes and no one seemed to know why we were never equipped with them.”41

Clements returned to banking, initially in Virginia, then with the Federal Reserve Bank in Charlotte, North Carolina, where he was managing director prior to his retirement in 1946.42

mrsmcq June 2, 2017

Notes

(For complete bibliographic entries, please consult the list of works and web pages cited.)

1 For his place and date of birth, see “William Thomas Clements.” For his place and date of death, see Ancestry.com, Virginia, Death Records, 1912-2014, record for William Thomas Clements. The photo is a detail from a group photo of Squadron 7 taken by Frank Hager Haskett at Ohio State University on August 15, 1917

2 See the postings by Clements’s daughter, Marjorie Kidd, at “William Clements (Clemmons).”

3 See “Gloucester Woman’s Club” on Eli T. Clements (William Thomas’s grandfather).

4 On William Thomas Clements’s father, see Ancestry.com, 1900 United States Federal Census, record for Ed I Clements.

5 See “William Thomas Clements.”

6 Clements, diary, August 7 and June 27, 1917.

7 “Ground School Graduations [for August 25, 1917]”; Clements, diary, August 28, 1917.

8 Clements, diary, October 2, 1917.

9 Clements, diary, October 3, 1917.

10 Clements, diary, October 7, 9, and 11, 1917.

11 Clements, diary, October 14 and 15, 1917; Foss, diary, October 13, 1917, identifies the major.

12 Clements, diary, November 1, 1917.

13 Clements, diary, November 3 and 4, 1917.

14 Clements, diary, November 17 and 18, 1917.

15 Clements, diary, November 30, 1917.

16 Foss, Papers, “Cadets of Italian Detachment Posted Dec 3rd.”

16a See Philpott, The Birth of the Royal Air Force, p. 401, on the planes flown by No. 33 Squadron.

17 Clements, diary, February 18, 1918.

18 Clements, diary, March 9, 1918; Pershing forwarded the recommendation on March 18, 1918; see cablegram 745-S.

19 Clements, diary, March 19, 1918.

20 Clements, diary, March 24, 1918.

21 Clements, diary, March 26–30, 1918, on ferrying; April 2, 1918 on his commission. Cablegram 985-R, dated, March 26, 1918, indicated the appointment was made; as usual, some days elapsed before the man commissioned was informed.

22 Clements, diary, April 4, 1918.

23 Clements, diary, April 13, 1918.

24 Clements, diary, April 20, 1918.

25 Clements, diary, April 29, 1918.

26 See the roster of officers of the 148th on pp. 61-63 of Taylor, A History of the 148th Aero Squadron. Details of Clements’s activities with operational squadrons are taken from his diary. Information about the 148th Aero is taken from Taylor, A History of the 148th Aero Squadron.

27 Clements, diary, August 1, 1918.

28 Clements, diary entry for August 26, 1918. It was apparently Lt. Col. Patrick Henry Lyon Playfair who gave this order; see Skelton and Williams, Lt. Henry R. Clay, p. 108. See Reed and Roland, Camel Drivers, p. 80, on the German squadrons moved towards this part of the front, and Chapter 7 for an extended description of the fatal encounter on August 26, 1918.

29 This quotation and the preceding are from Clements’s diary, August 26, 1918.

30 This quotation and the preceding are from Clements’s diary, August 27, 1918

31 Clements, diary, August 30, 1918.

32 Clapp, A History of the 17th Aero Squadron, p. 45.

33 Clements, diary, September 19, 1918.

33a Clapp, A History of the 17th Aero Squadron, p. 49. The blue-tail Fokkers were probably planes of Jagdstaffel 36, which was stationed at Aniche at this time. See “Blue-tail Fokkers, Sept. 24, 1918.”

34 Clements, diary, September 24, 1918.

35 Clapp, A History of the 17th Aero Squadron (1918), pp. 77 and 108.

36 See bombing reports in Clapp, A History of the 17th Aero Squadron, pp. 106-22.

37 Clements, diary, summary entry for October 2–19, 1918.

38 I have not found a record of his being awarded the D.S.C.

38a “List of Officers Who Have Demonstrated Exceptional Ability,” p. 312.

39 See Ancestry.com, U.S., Army Transport Service, Passenger Lists, 1910-1939, record for William T Clements.

40 Clements, diary, July 5, 1917. Ancestry.com, New York, New York, Marriage Index 1866-1937, record for Wm T Clements.

41 Clements, “World War Diary of W. T. Clements 1917-1918,” p. 104. The number of men from the two detachments killed was actually about forty-four.

42 “William Thomas Clements”; “William T. Clements.”