(Weston, West Virginia, February 11, 1896 – Weston, West Virginia, January 2, 1974).1

Everett’s family was complicated. He apparently went by his mother’s maiden name. She married three times, and each of her husbands married at least twice; Everett had numerous siblings, half-siblings and step-siblings.2 His was probably a hard-scrabble upbringing; his mother worked as a laundress and his stepfather did odd jobs as a day laborer.3 Everett attended West Virginia University for a time and was at West Point from June 1916 until January of 1917.4 When he registered for the draft on June 5, 1917, he was working for B. F. Goodrich in Akron, Ohio. He attended ground school at Ohio State University, graduating with the class of September 1, 1917.5

Along with most of his O.S.U. classmates, Everett was selected for training in Italy, and he joined the 150 men of the “Italian” or “second Oxford detachment” who sailed to England on the Carmania. They departed New York for Halifax on September 18, 1917, and departed Halifax as part of a convoy for the Atlantic crossing on September 21, 1917. When the Carmania docked at Liverpool on October 2, 1917, the detachment learned to their initial consternation that they would not go to Italy but instead remain in England and repeat ground school at Oxford’s School of Military Aeronautics. While at Oxford, Everett palled around with his O.S.U. ground school classmates Fremont Cutler Foss and Robert Brewster Porter, enjoying Sunday dinner with them at Buol’s the week of their arrival and a bike ride to Dorchester-on-Thames two weeks later.6 On November 3, 1917, he travelled with most of the detachment to Harrowby Camp near Grantham in Lincolnshire to attend machine gun school.

In mid-November fifty of the men were selected to go to flying schools, but Everett was among those who remained at Grantham through Thanksgiving and the end of November.7 Finally, on December 3, 1917, the remaining men were posted to flying squadrons, and Everett, along with Joseph Raymond Payden, Porter, and Andrew Joseph Shannon, was assigned to No. 38 Squadron, which had its headquarters at Melton Mowbray in Leicestershire and was tasked with pilot training by day and air defense against Zeppelins by night.8 There is a photo of Everett at No. 38 with fellow cadets in training Payden and Porter and English officers in J.R.: Joseph R. Payden, 1915-1925, the compilation of photos and documents compiled by Payden’s children.

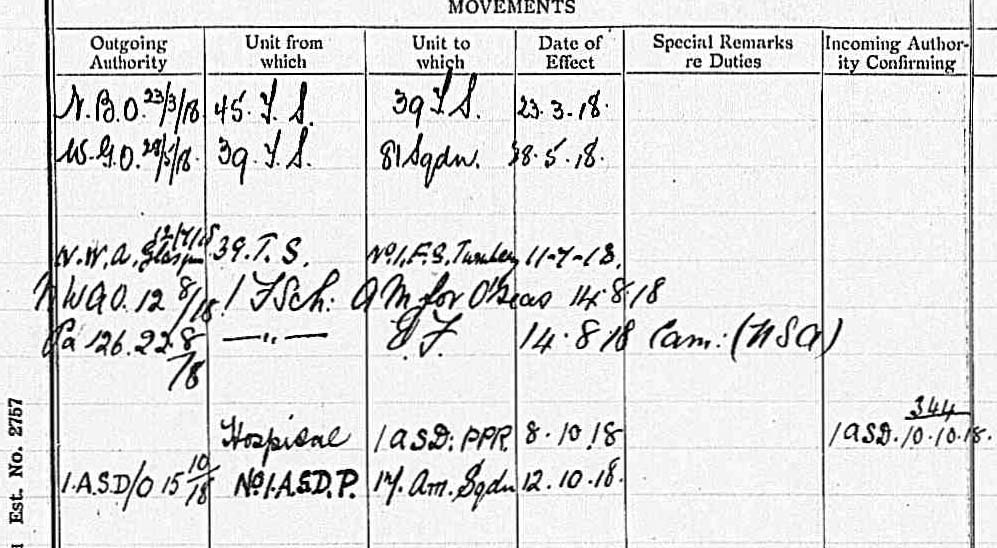

At some point Everett was posted to No. 45 Training Squadron at South Carlton, about twenty-five miles north of Grantham.9 From there, on March 23, 1918, he was assigned to No. 39 T.S., also at South Carlton.

Everett was among those men whom Pershing recommended be commissioned “First Lieutenants Aviation Reserve non-flying” in a cable dated April 8, 1918.10 It had been brought to Pershing’s attention that many aviation cadets had come to Europe expecting to begin flight training immediately but had instead kicked up their heels for months. As Pershing wrote in a cablegram dated March 13, 1918, “All of those cadets would have been commissioned prior to this date if training facilities could have been provided. These conditions have produced profound discouragement among cadets.” To remedy this injustice, and to put the European cadets on an equal footing with their counterparts in the U.S., Pershing asked permission “to immediately issue to all cadets now in Europe temporary or Reserve commissions in Aviation Section Signal Corps. . . .” Washington approved the plan in a cablegram dated March 21, 1918, but stipulated that the commissioned men be “put on non-flying status. Upon satisfactory completion of flying training they can be transferred as flying officers.” It took over a month for Washington to respond to Pershing’s April 8, 1918, cable and to confirm the recommended commissions.10a Everett may well in the meantime have completed enough flying and training to make the “non-flying status” irrelevant; he was, in any case, put on active duty status on May 30, 1918.10b

Around the same time, Everett was posted to No. 81 Squadron (a training squadron at Scampton, just north of South Carlton, apparently equipped with Camels).11 From there he went to No. 1 Flying School at Turnberry on July 11, 1918. He was ready to go overseas on August 14, 1918, and was assigned to the U.S. 17th Aero Squadron the next day.12

The 17th Aero Squadron, to which a number of second Oxford detachment members had already been assigned, flew Camels. Like the 148th, it was American in personnel, but stationed on the British Front and under the tactical command of the R.A.F. until very late in the war. When Everett was assigned, the 17th Aero was still stationed at Petite Synthe near Dunkirk, but soon moved south to Auxi-le-Château northwest of Doullens, where their job was to escort R.A.F. bombers, and also to do their own bombing and strafing.13

Everett was assigned to C flight, commanded by Lloyd Andrews Hamilton. However, Everett was not well when he arrived, and he apparently did not participate in bombing missions in the latter part of August 1918.14 On September 2, 1918, he was admitted to hospital, and only returned to the squadron on October 13, 1918.15 As a commentary on the considerable turnover of pilots in the 17th, many of whom were wounded, killed, or taken prisoner, it has been noted that Everett, “by virtue of coming into the field twice, [was] one of the few members of the unit who knew the first players as well as the last.”16 Everett’s name does not appear among those participating in the bombing reports for October 14 and 24, 1918, but there were other patrols in October in which he may have participated.17

As the effort by the British armies to take Cambrai progressed, the lines moved eastwards until they were almost beyond the flying distance of the 17th’s Camels. Preparations were made for the squadron to relocate closer to the lines.18 However, this move was preempted towards the end of October when word was received that the 17th was to leave the B.E.F. and the R.A.F. and move to the American sector. On November 1, 1918, the men began the train journey south, arriving, finally, near Toul on November 4, 1918, (where photos were taken), and there they joined in the armistice celebrations on the 11th.19 Then came the long wait for transport home; Everett filled in some of his time at Toul ferrying Spads to Issoudun.20 He sailed back to the U.S. on the Cedric, departing Brest January 26, 1919, and arriving at New York on February 4, 1919.21

After the war, Everett returned for a time to Akron, Ohio, and the 1930 census lists him there as an aviator.22 Not long thereafter he moved back to his hometown of Weston in West Virginia.23

mrsmcq June 30, 2017

Notes

(For complete bibliographic entries, please consult the list of works and web pages cited.)

1 For his place and date of birth, see Ancestry.com, U.S., World War I Draft Registration Cards, 1917-1918, record for Albert Frank Everett. For his place of burial and date of death, see Sharon, “Albert F. Everett.” It is probable that he died in Weston, but I have not found a confirming obituary. The photo is a detail from a group photo of Squadron 8 at the Ohio State University School of Military Aeronautics.

2 Information is based on documents available at Ancestry.com.

3 See Ancestry.com, 1910 United States Federal Census, records for Albert Everett, Alice Aylor, and George Aylor.

4 See Everett’s draft registration (cited above) and the Official Register of the Officers and Cadets United States Military Academy for 1917, pp. 41, 51, and 60.

5 “Ground School Graduations [for September 1, 1917].”

6 Foss, diary entries for October 7 and 21, 1917.

7 See Foss, diary entry for November 15, 1917.

8 Foss, “Cadets of Italian Detachment Posted Dec 3rd” (in Foss, Papers); Wikipedia, “No. 38 Squadron RAF.”

9 Information on Everett’s training and posting is taken from The National Archives (United Kingdom), Royal Air Force officers’ service records 1918-1919, record for Albert F. Everett.

10 See cablegram 874-S.

10a See cablegrams 726-S (March 13, 1918), 955-R (March 21, 1918), and 1303-R (May 13, 1918).

10b See McAndrew, “Special Orders No. 205.”

11 On No. 81 Squadron, see Philpott, The Birth of the Royal Air Force, p. 418, and Brown, “A Short History of No. 81 Squadron.”

12 Clapp, A History of the 17th Aero Squadron, p. 157.

13 The date of the move to Auxi is reported differently by Clapp A History of the 17th Aero Squadron, p. 37, and by Reed and Roland, Camel Drivers, p. 64. Murton Campbell’s diary is probably reliable in recording the move as having occurred on August 17, 1918.

14 See Reed and Roland, Camel Drivers, p. 86, and Clapp, A History of the 17th Aero Squadron, pp. 98–106.

15 Clapp, A History of the 17th Aero Squadron, pp. 158 and 159.

16 See Clapp, A History of the 17th Aero Squadron, pp. 158, 159, for the dates of his hospital admission and return to the squadron. The quotation is from Reed and Roland, Camel Drivers, p. 114.

17 Clapp, A History of the 17th Aero Squadron, pp. 142–46; Reed and Roland, Camel Drivers, p. 114-16.

18 Reed and Roland, Camel Drivers, p. 115. (See this page also for a photo of Everett supplied by Lorenz Kneedler Ayers.)

19 Dates of departure and arrival are taken from Clements’s diary entries for those dates.

20 Reed and Roland, Camel Drivers, p. 124.

21 See War Department, Office of the Quartermaster General, Army Transport Service, Lists of Incoming Passengers, 1917 – 1938, Passenger list for officers, on S. S. Cedric.

22 Ancestry.com, 1930 United States Federal Census, record for Albert F Everett.

23 Ancestry.com, 1940 United States Federal Census, record for Albert Everett.