(Cambridge, Massachusetts, December 25, 1895 – Waltham, Massachusetts, April 17, 1992).1

Oxford & Grantham ✯ Training to Fly, C.D.P. ✯ 155th Aero and afterwards

Joseph Andrew Shannon’s father, Patrick J. Shannon, emigrated in 1883 from County Clare in Ireland to Boston.2 There he met Honora Canavan, also Irish born, and they married in 1891, settling initially in Cambridge, where Andrew Joseph Shannon was born, the third of six children. Patrick J. Shannon worked initially as a laborer, but by 1910 had become a salesman for a wholesale oil and gas company; he bought a house in Waltham, where Joseph Andrew Shannon attended South Grammar School and presumably high school; he did not attend college.3 When he registered for the draft on June 5, 1917, Shannon indicated he was working as a clerk in Boston for Hornblower & Weeks, an investment banking and brokerage firm, and that he had had no military experience.4

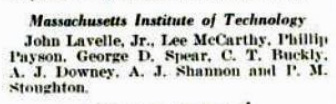

Shannon evidently applied to and was accepted by the Aviation Section of the Signal Corps. He attended ground school at the School of Military Aeronautics at M.I.T.; his name appears on graduation lists for both August 18, 1917, and September 1, 1917—there seems to have been some confusion regarding the class lists at the M.I.T. S.M.A.5 The September 1, 1917, class was a small one, and out of eight men, six, including Shannon, chose or were chosen to do their advanced training in Italy.

These six were thus among the 150 men of the “Italian” or “second Oxford detachment” who sailed to Europe on the Carmania. They left New York on September 18, 1917, heading initially for Halifax, where the Carmania joined a convoy for the Atlantic crossing. The men travelled first class and had few obligations other than attending Italian lessons, conducted by Fiorello La Guardia, and, once the convoy entered dangerous waters, taking turns at submarine watch. The Carmania arrived at Liverpool October 2, 1917; the expectation was that the men would cross the Channel and proceed to Italy.

Oxford and Grantham

On disembarking the men were informed that they were to remain in England and would attend ground school (again). They boarded a train for Oxford, where they were enrolled in the Royal Flying Corps’s No. 2 School of Military Aeronautics at Oxford University (where another, smaller, group of American cadets, the “first Oxford detachment,” was already ensconced). Initially disappointed by the change of plans, the men soon became reconciled to it. Their British instructors, unlike the ones in the U.S., had had war flying experience, and this added considerable interest to the course work. Since the men had already covered much of the material, they did not have to study especially hard, and they enjoyed Oxford hospitality and explored the town and surrounding countryside.

The men were eager to start flying training, but more disappointment was in store for most of them. Four weeks after their arrival at Oxford, twenty men from the detachment were posted to No. 1 Training Depot Station at Stamford to begin flying training, but the others, including Shannon, set out on November 3, 1917, for Harrowby Camp near Grantham in Lincolnshire to attend machine gunnery school. As Parr Hooper, also sent to Grantham, remarked: “It looks like we got sent here because there was no other place to send us to—playing for time.”6 Fifty men were sent to squadrons in mid-November, but, again, Shannon was not among them.

Training to fly, C.D.P.

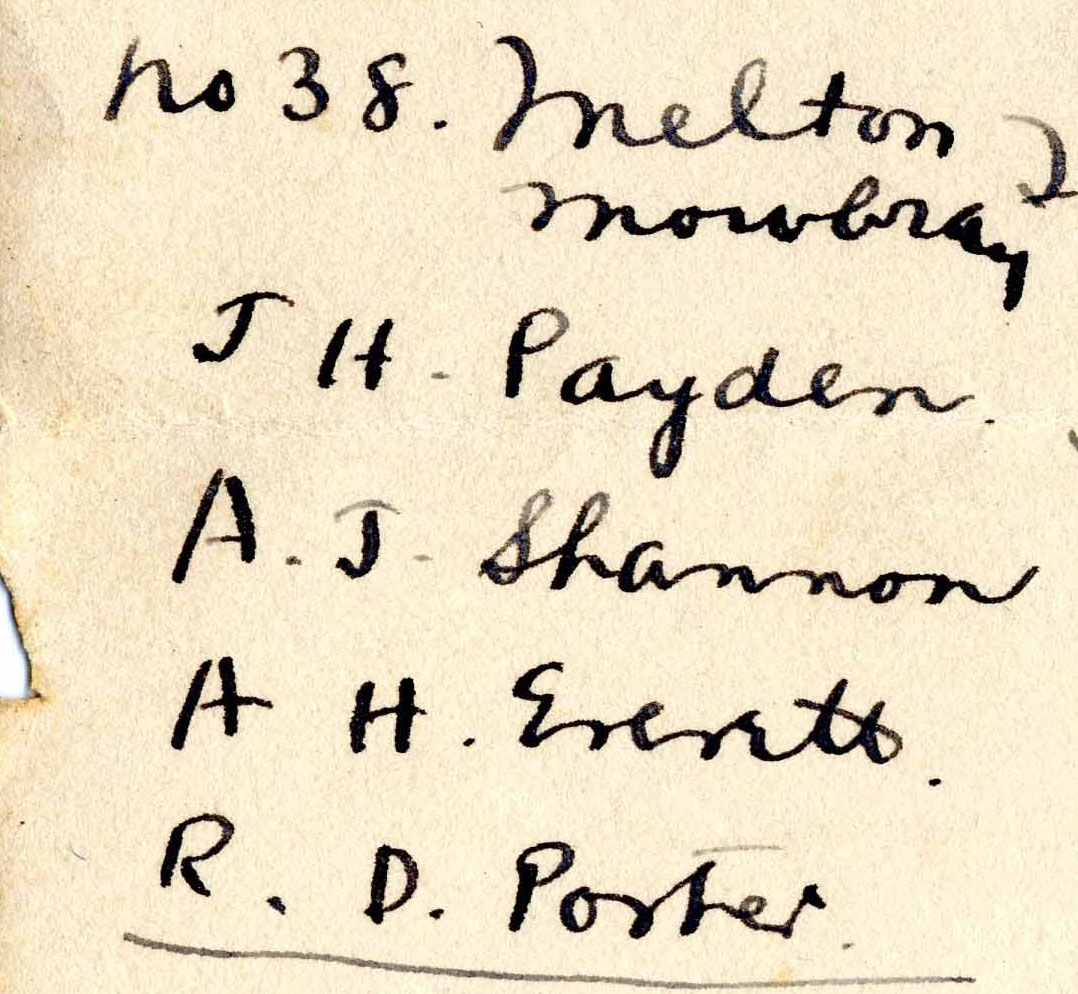

Finally, on December 3, 1917, the remaining men were posted to flying squadrons, and Shannon, along with Albert Frank Everett, Joseph Raymond Payden, and Robert Brewster Porter, was assigned to No. 38 Squadron. 7 No. 38, which had its headquarters at Melton Mowbray in Leicestershire, was tasked with pilot training by day and air defense against Zeppelins by night.8 At the end of 1917, the squadron was flying F.E.2b’s and F.E.2d’s, two-seat fighter and bomber biplanes—not suitable for primary flight training, but the cadets could certainly have gone up as passengers. The squadron’s three flights operated out of Leadenham, Buckminster, and Stamford; the second Oxford detachment men probably spent most of their time at one of these sites.9

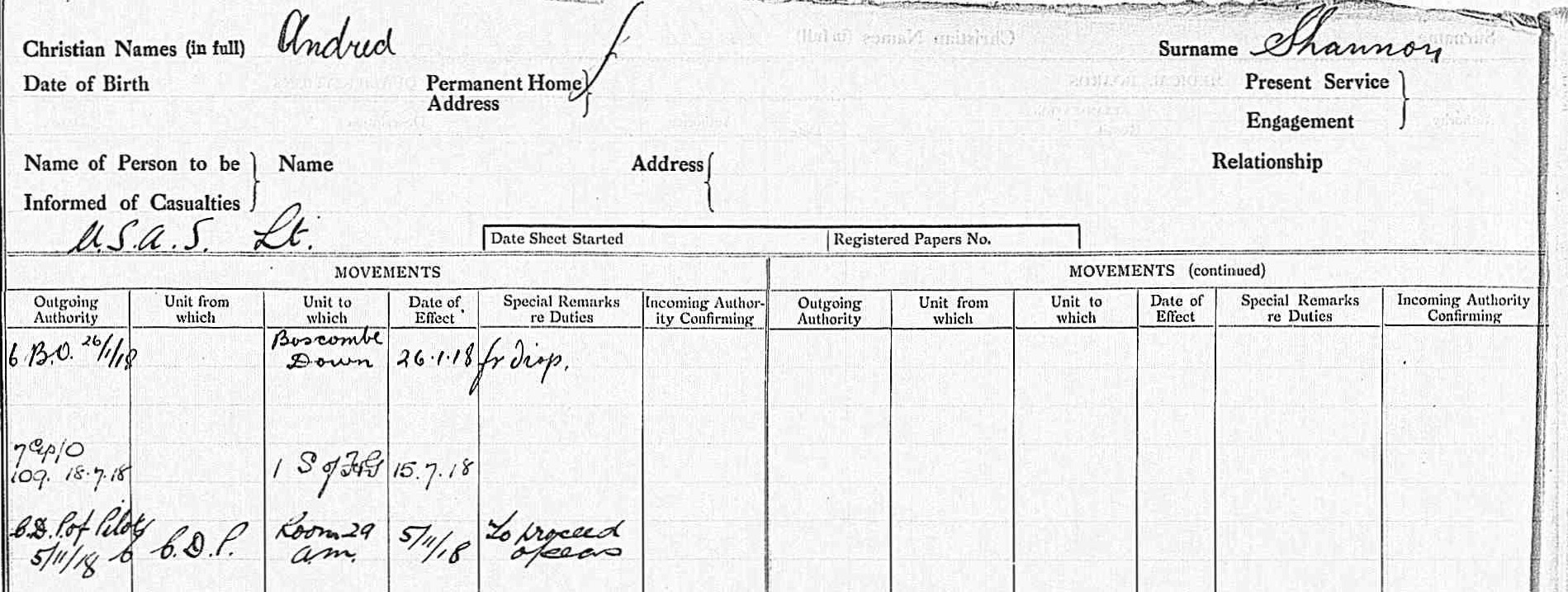

According to Shannon’s R.A.F. service record, he was posted on January 26, 1918, to Boscombe Down.10 This presumably meant that he was assigned to No. 6 Training Depot Station. The planes available at 6 T.D.S. included Avros, B.E.2c’s, B.E.2e’s, and DH6s—all two seaters designed or now used for training—and DH.4s, DH9s, and FK8s, two-seater operational aircraft used for reconnaissance and bombing.11

In early April Shannon and many of his fellow second Oxford detachment members were recommended by Pershing for commissions—but as “First Lieutenants Aviation Reserve non flying.”12 Earlier in the year it had been brought to Pershing’s attention that many cadets had been held up in their progress towards commissions by the limited training facilities. On March 13, 1918, he had cabled to Washington requesting permission “to immediately issue to all cadets now in Europe temporary or Reserve commissions in Aviation Section Signal Corps. . . .”13 Washington approved the plan in a cable dated March 21, 1918, but stipulated that the commissioned men be “put on non-flying status. Upon satisfactory completion of flying training they can be transferred as flying officers.”14 Hence the “non-flying” status attached to the commission recommendation for Shannon and others in the April 8, 1918, cablegram. It took over a month and some prodding, but finally, on May 13, 1918, Washington cabled back approval.15 Shannon was placed on active service May 30, 1918.16

It may be that Shannon remained at Boscombe Down until July 15, 1918, when his R.A.F. service record notes his assignment to “1 S of F&G,” although it is also possible that the sketchy service record fails to note interim postings. In any case, Shannon would have proceeded to Turnberry and Ayr on the west coast of Scotland, where the No. 1 School of Fighting was located, to finish up his training with instruction in aerial fighting and gunnery.

After completing his training, Shannon, like many other second Oxford detachment members, was apparently posted to the Central Despatch Pool in London and began serving as a ferry pilot, presumably flying planes from one location to another within England and probably also from England to France. It was not until November 5, 1918, that he was posted overseas.17 According to Shannon’s niece, who knew him well, he was at some point shot down behind enemy lines and hidden and cared for by a French farmer for some months until the area was liberated. I find no documentation of this, but this may simply reflect inadequate or destroyed records of the Central Despatch Pool; it seems not unreasonable to assume that Shannon strayed across the lines while ferrying a plane, with unfortunate results, including, according to the niece, the loss of sight in one eye.

The 155th Aero and afterwards

James J. Sloan, in his Wings of Honor, indicates that Shannon was at least briefly at the American No. 3 Aviation Instruction Center at Issoudun in the Loire region of central France and that from there, on November 18, 1918—i.e., shortly after the armistice—he joined the 155th Aero Squadron.18 The 155th was a night bombardment squadron flying DH-4s. There had been ambitious plans for a large number of American night bombardment squadrons flying Handley Pages; the hope was that they would begin deploying by mid-1918.19 Production of Handley Pages was slower than expected, and in the end, the only night bombardment squadron to reach the front before November 11, 1918, was the 155th with its DH-4s. According to Sloan, a “lack of night-flying equipment and facilities” meant that the armistice “came before any real mission effort could be made.”20 A squadron history indicates that the 155th, based at Colombey-les-Belles, “did reconnaissance flying looking for crashed planes.”21

Shannon was able to set out for the U.S. fairly soon after the war: he sailed from Marseilles on the America on February 10, 1918; among his ship mates was his fellow second Oxford detachment member George Clark Sherman.22 He returned to Waltham, Massachusetts, and resumed work in the financial industry.23

Notes

(For complete bibliographic entries, please consult the list of works and web pages cited.)

1 Shannon’s place and date of birth are taken from Ancestry.com, U.S., World War I Draft Registration Cards, 1917–1918, record for Andrew Joseph Shannon. His place and date of death are taken from Ancestry.com, Massachusetts, U.S., Death Index, 1970-2003, record for Andrew J Shannon. I have not been able to find a photo of him.

2 See Ancestry.com, Massachusetts, U.S., State and Federal Naturalization Records, 1798-1950, record for Patrick Shannon. The address given on this naturalization petition helps establish that this is the correct Patrick Shannon. I should note that the dates of emigration given on census forms are consistently later, but still in the 1880s. Other information on the family is taken from documents available at Ancestry.com.

3 See [Waltham, Massachusetts], Inaugural Address, p. 66, regarding school attendance. I find no record of college attendance, and his niece, Dorothy Shannon Swithenbank, has confirmed that he did not go to college.

4 See draft registration, cited above.

5 “Ground School Graduations [for August 18, 1917]”; “Ground School Graduations [for September 1, 1917].” William Ludwig Deetjen similarly appeared on more than one M.I.T. S.M.A. graduation list.

6 Hooper, Somewhere in France, letter of [November] 4, 1917.

7 Foss, “Cadets of Italian Detachment Posted Dec 3rd” (in Foss, Papers).”

8 Wikipedia, “No. 38 Squadron RAF.”

9 On No. 38’s planes and locations, see p. 403 of Philpott, The Birth of the Royal Air Force

10 The National Archives (United Kingdom), Royal Air Force officers’ service records 1918–1919, record for Andred F. Shannon [sic].

11 On the aircraft at Boscombe Down, see Sturtivant, Hamlin, and Halley, Royal Air Force Flying Training and Support Units, p. 294.

12 Cablegram 874-S, dated April 8, 1918.

13 Cablegram 726-S.

14 Cablegram 955-R.

15 Cablegram 1303-R.

16 McAndrew, “Special Orders No. 205.”

17 See Shannon’s R.A.F. service record, cited above.

18 Sloan, Wings of Honor, p. 430. And see Dillenback, “155th Aero Squadron (Night Bombardment),” p. 41, where Shannon’s name appears on the list of commissioned officers.

19 See Night Bombardment Section, Air Service, A.E.F., England, passim.

20 Sloan, Wings of Honor, p. 381.

21 Dillenback, “155th Aero Squadron (Night Bombardment),” p. 40. There is some confusion in this history regarding dates and the squadron’s movements.

22 Ancestry.com, U.S., Army Transport Service, Passenger Lists, 1910-1939, record for Andrew Joseph Shannon.

23 Ancestry.com, 1920 United States Federal Census, record for Andrew Shannon.