(Chicago, Illinois, April 16, 1892 – Ramsey County, Minnesota, September 12, 1971).1

Lawton’s father, Charles Tillinghast Lawton, was a grandson of Gardner Lawton and, through him, a descendant of George Lawton, an early settler of Rhode Island. Lawton’s maternal grandparents had emigrated from England and Germany.2 Lawton had two sisters, eight and ten years older than himself; his mother, Madeleine Sophy Cleaver Lawton, died shortly after he was born.3 The family valued education: his mother had been a teacher before her marriage.4 His older sister, Emily Madeleine, followed the same profession, as did his other sister, Edith Charlotte, a graduate of the University of Chicago, prior to her marriage.5

Lawton attended the University of Illinois, where, according to his draft registration card, he served as an infantry private in the University of Illinois cadet regiment. After receiving his B.A. in liberal arts and journalism in 1915, he went to California—perhaps drawn by recollections of his maternal grandfather, who had participated in the Gold Rush before settling in Chicago—to teach at a private preparatory school, Manzanita Hall, in Palo Alto.6 The following year Lawton was accepted for the aviation service and returned to Illinois to attend ground school at Champaign in the class that graduated August 25, 1917.7

About one third of the men in this class, including Lawton, chose or were chosen to go to Italy for flight training and were thus among the 150 men of the “Italian” or “second Oxford detachment” who sailed to England on the Carmania. The ship departed New York on September 18, 1917, and, after a stopover at Halifax to meet up with a convoy for the Atlantic crossing, docked at Liverpool on October 2, 1917. Once in England the men learned that Italy was no longer their destination; instead they were to attend ground school, again, this time at the Royal Flying Corps’s No. 2 School of Military Aeronautics at Oxford University. There was initially considerable grumbling about this turn of events; everyone wanted to start flying as soon as possible. But they made their peace with the situation and enjoyed what Oxford had to offer: recreation, sightseeing, and socializing with town and gown, who welcomed the American military in this fourth year of the war. The cadets (as they were now called) were divided into two groups. Ninety of the men were housed at Christ Church College and sixty at Queen’s. Cadet William Ludwig Deetjen was in charge of the smaller contingent, which probably included Lawton; Deetejen noted in his diary in mid-October that he was “going to a dance tonight with Lawton, a Fiji”—they had both joined the Phi Gamma Delta fraternity while at college.8

A month after their arrival in England, the men learned that their time at Oxford was up. Twenty men were selected to go to Stamford to start flying; Lawton was among the remaining 129 who were ordered to attend machine gun school at Harrowby Camp near Grantham in Lincolnshire (according to the War Birds entry for November 6, 1917, one man, James Whitworth Stokes, stayed behind in Oxford to be operated on for appendicitis). On November 3, 1917, the men got up early to pack for the train journey north. It took about six hours, including an hour stop for lunch near Bletchley Park. A little further on, at Sandy, they changed cars, and Lawton completed the third class journey in a compartment with six others, including Fremont Cutler Foss, who got his compartment mates to autograph his diary page for that day. In a letter home, one of them, Parr Hooper, recounted how

We arrived at Grantham about 3:30. When we formed up outside of the station a full band fell in with us and we marched thru the town and out here with thrilling music. . . . This camp is a very large affair on a muddy hill side farm. We have a section of very nice huts, about 9 men to a hut, and our own mess hall with a comfortable ante-room. They served us a good dinner as soon as we arrived. Then we sorted out our baggage from where it had been unloaded from trucks and toted it to our huts. After putting up our cots and getting arranged generally we had supper at 7:45. . . . We will be here 4 months and then, it seems, will go to an aerial gunnery school. It looks like we got sent here because there was no other place to send us to—playing for time.9

Hooper was right about the reason the men were sent to Grantham, but wrong about the length of their stay. All of the men were assigned to training squadrons by early December, with fifty of them posted halfway through November. On November 14, 1917, after two weeks of Vickers machine gun instruction and practice, Lawton learned that he was among the fifty selected to move on to training squadrons on November 19, 1917.10 His fellow cadet Murton Llewellyn Campbell wrote in his diary that day that

5:00 is rather early for me but it had to be done because I was one of the lucky ones to be posted to a Flying field. . . . Doug[lass] and I are posted at Doncaster, together with 8 others: namely, Goodnow, Zellers, Armstrong, Berry, and Doug in the 41st Squadron and Oberst, Sweeney, Lawton, Desson, and myself in the 49th. . . . The 49th was billeted in private homes. Desson, Lawton, and I together in a very fine home. The people appear to be excellent. In fact, too good to be true. Our Flight Commander, Capt. Smith, gave us a joy ride about 3:30 this afternoon. . . . We will learn entirely on M.F S.H. [Maurice Farman Shorthorn] pushers.11

I have found little information about Lawton’s training stations after Doncaster, but photos in Joseph Kirkbride Milnor’s album suggest that he was for a time at No. 61 Training Squadron at South Carlton.12 In the latter part of February he was evidently in the Midlands, as Deetjen recounted running into him in Nottingham on February 21, 1918.13 There is a list of the planes he was instructed on during the first months of 1918. After the Maurice Farman S.H. he went on to Avros, and then Sopwith Pups and Camels.14 By mid-March he had done enough flying to be recommended for a lieutenant’s commission. The cable forwarding the recommendation is dated March 25, 1918, and the confirming response April 5, 1918.15 He was placed on active duty on April 15, 1918, at which point he was at Turnberry in Scotland, presumably on a course in aerial gunnery prior to finishing his training at the No. 1 School of Aerial Fighting up the coast at Ayr.16

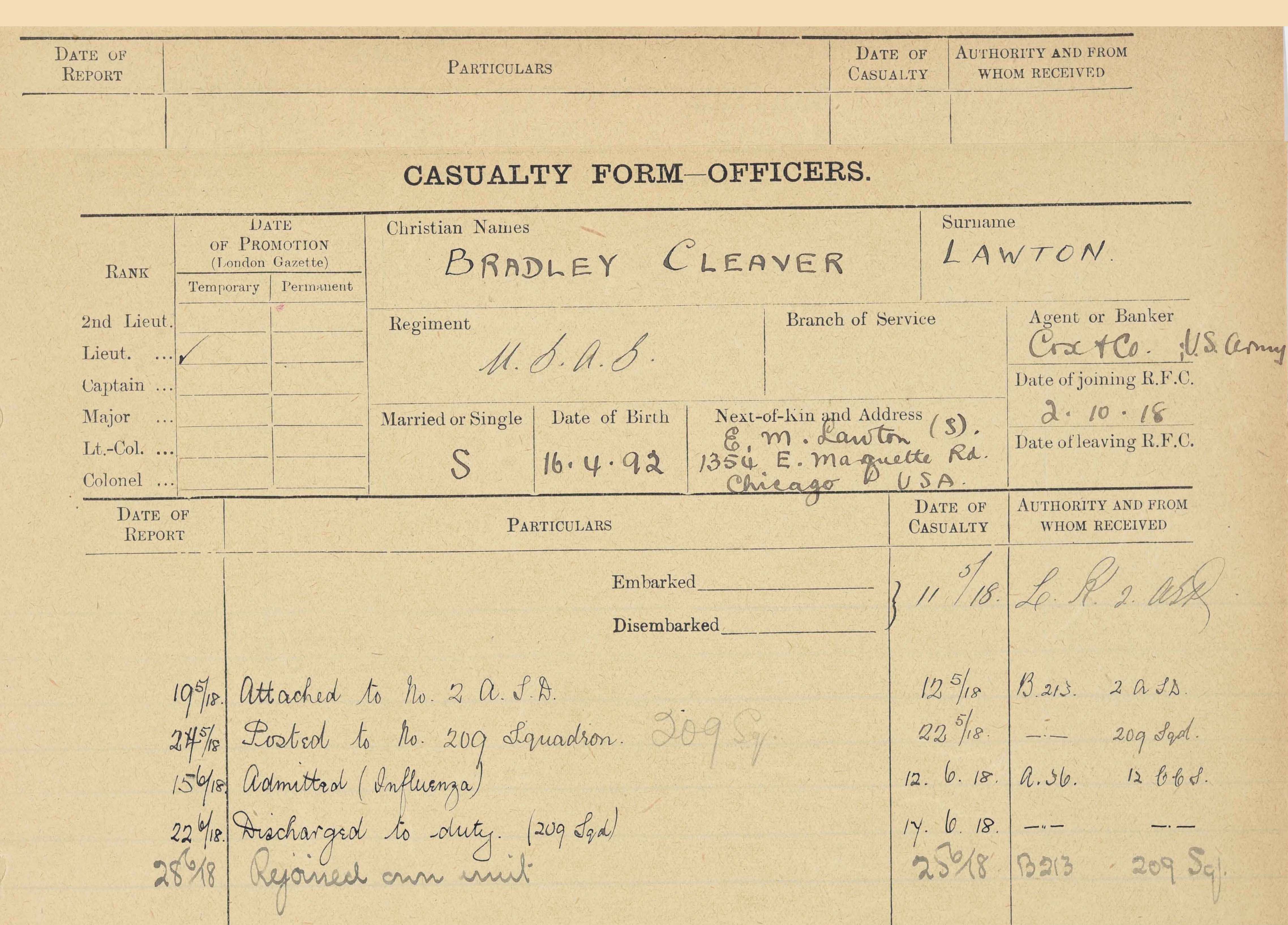

On about May 11, 1918, Lawton was assigned to the R.A.F. and ordered to 2 A.S.D., meaning he crossed the Channel to await further assignment.17 On May 22, 1918, he was posted to No. 209 Squadron R.A.F., a Camel squadron stationed at that time at Bertangles, a few miles north of Amiens—which city, as a result of the first phase of the German Spring Offensive, was now only about fifteen miles from the front.

Frank Aloysius Dixon, a fellow second Oxford detachment member assigned to 209 around the same time, recalled that “the German advance lines were then too near for comfort.”18 Two other second Oxford detachment members were also at 209: William Joseph Armstrong and Leonard Joseph Desson.19 Other detachment members were or would soon be at Nos. 48, 65, and 84 Squadrons, R.A.F., which were also flying out of Bertangles.

According to the 209 Squadron record book, Lawton’s first flight with the squadron was a fifty minute practice flight on May 25, 1918, when he flew Camel D3373, the plane he would fly during most of his time with 209.20 The next four days involved more practice flights and target practice, as well as the delivery of a new machine (D9588) from the 2nd Air Issues Section at Saint-André au Bois.21 In the afternoon of May 30, 1918, Lawton was assigned to patrol the area between the aerodrome and Amiens; the hour and a half was uneventful, and he observed no enemy aircraft. He had evidently been assigned to B flight, for the next afternoon he participated in a three-plane “Spec[ial] Miss[ion] Intercepting WEA,” led by B flight commander Oliver Colin Le Boutillier; the other pilot was Lionel Frank Lomas, also recently assigned to 209.22 209 Squadron pilot Cedric Nevill Jones described missions of this type as “dashes after Hun two-seat artillery observation machines. Three of our aircraft were always on standby for these jobs. . . a Klaxon was sounded . . . and the standby pilots raced to their machines [and were] off the ground in two minutes after calling at the office for the chit with the location of the enemy aircraft. . . . It was a very unrewarding business because the Hun invariably saw you coming at a very great distance and were away like lightning. . . .”23 On this day it appears that another squadron had also been alerted, as 209’s B flight “Observed E.A. inland which were attacked by S.E’s.”

This same day, May 31, 1918, Lawton took part in his first high offensive patrol. He thus crossed the lines a mere nine days after arriving at the squadron, in breach of the convention that new men got two to three weeks of orientation before flying over enemy territory. The “H.O.P.” this day was again a three-plane formation with Le Boutillier leading; the third pilot was Mark Adamson Harker. They took off at 6:40 p.m. and flew approximately twenty miles in a southwesterly direction. In the vicinity of Vauvillers they had an encounter with nine enemy planes. The syntax of the remarks in the record book leaves unclear who attacked whom, but B flight came away unscathed, having fired at an Albatros, which was “driven down out of control.”

Over the next nine days, Lawton participated in eleven missions. On several of the three-plane formation missions, the third pilot flying with him and Le Boutillier was second Oxford detachment member William Joseph Armstrong. Twice, on W.E.A. special missions, Lawton had to return early; the record book gives no explanation, but it seems likely that the engine of D3373 was giving trouble. Lawton took part in five high offensive patrols during this period, memorably on June 9, 1918, the opening day of the Montdidier-Noyon offensive. This was, unusually, an eleven-plane formation, and bombs were carried and dropped “in woods between Boussicourt and Davenescourt” and also just east of Montdidier. Lawton’s participation was cut short about halfway into the mission as his engine was vibrating, and he had to return to the aerodrome.

Not long after this, the squadron was hit hard by influenza. On June 12, 1918, Lawton, Lomas, and Hubert Mason (apparently also of B flight) were admitted to No. 12 Casualty Clearing Station at Longpré, about fourteen miles west of Bertangles (12 C.C.S. was one of the medical facilities serving the British Fourth Army). Harker and Le Boutillier were hospitalized on June 13 and 14, respectively.24 Under “Pilots available” on June 14, 1918, the record book entry reads: “8 over the lines, 2 this side, 1 on leave, 11 sick.”

Lawton was discharged from No. 12 C.C.S. on June 17, 1918.25 When he next flew a mission, a six-plane high offensive patrol the evening of June 20, 1918, the leader was William John MacKenzie; Armstrong and Mason were also in this formation. Once again they carried and dropped bombs, this time on Proyart (Mason failed to return and was later found to have become a prisoner of war). Lawton flew his final mission with 209 Squadron on June 23, 1918. This was an early morning three-plane W.E.A. led by MacKenzie; the third pilot was Wilfred Augustus Stead.

Soon after this flight, Lawton, along with Dixon, Armstrong, and Desson, was ordered to join the U.S. 17th Aero Squadron (also flying Camels) at Petite Synthe on the coast near Dunkirk, about seventy miles due north of Bertangles. Arriving on or about June 26, 1918, they joined a number of other members of the second Oxford detachment already assigned there.26 The 17th, along with the 148th, was American in personnel, but stationed on the British Front and under the tactical command of the R.A.F. until late in the war. Lawton, with Armstrong, was assigned to C flight, which was led by Lloyd Andrews Hamilton, with Henry Bradley Frost as deputy commander.27 After about three weeks of getting to know their equipment and their territory while working on formation flying, the 17th flew their first offensive patrol on July 15, 1918. They began escorting DH.9 bombers into German occupied territory on July 20, 1918.28

Lawton, however, had already encountered unexpected difficulties. While he was flying Camel D6589 on July 11, 1918, his engine failed; his effort to restart it by diving was unsuccessful, and he crashed at Adinkerke, near the coast halfway between Petite Synthe and the lines. He apparently hit his face against the butts of the Camel’s machine guns and came out of the crash with “smashed cheeks and a lacerated forehead.” He carried on and had another forced landing a week later, but the aftereffects of his initial crash, perhaps compounded by his earlier bout of influenza, led to his being sent to No. 13 General Hospital (Boulogne) on July 26, 1918. His name was “dropped from rolls” two days later, and his aviation career was over.29

I find no record of Lawton’s activities between his initial hospitalization and his departure for the U.S. at the end of November. When he did return home, on the Mauretania, he travelled in the company of a number of other second Oxford detachment members, some of whom had been P.O.W.’s, some of whom had been wounded.30 None of them, however, were recorded as medical cases on the ship manifest, suggesting that all had recovered. It seems a reasonable surmise that they were given desk or instructional jobs during the latter part of their time overseas.

Once back in the U.S., Lawton initially worked in advertising in Missouri and then for the State Board of Education in Minnesota.31

mrsmcq February 19, 2019

Notes

(For complete bibliographic entries, please consult the list of works and web pages cited.)

1 Lawton’s place and date of birth are taken from Ancestry.com, U.S., World War I Draft Registration Cards, 1917–1918, record for Bradley Clever [sic] Lawton. His place and date of death are taken from Ancestry.com, Minnesota, Death Index, 1908-2002, record for Bradley C. Lawton. The photo is a detail from a photo taken in August 1917 of Squadron F at the University of Illinois School of Military Aeronautics.

2 Information on Lawton’s descent is based on documents available at Ancestry.com. Family trees trace his ancestry to George Lawton; the documentation is in places thin.

3 See Ancestry.com, Cook County, Illinois, Deaths Index, 1878-1922, record for Madeleine S Lawton.

4 On Lawton’s mother’s occupation, see the entry for her in Hutchinson, comp., The Lakeside Annual Directory of the City of Chicago (1878–79).

5 On Emily Lawton, see Ancestry.com, 1920 United States Federal Census, record for Emily Lawton. On Edith Lawton, see Alumni Directory The University of Chicago 1913, p. 164.

6 See The Illio 1916, p. 89. On Lawton’s grandfather, William Cleaver, see the entry for him on p. 107 of Bateman, et al., eds., Historical Encyclopedia of Illinois (vol. 1).

7 “Ground School Graduations [for August 25, 1917].”

8 Deetjen, diary entry for October 13, 1917.

9 Hooper, Somewhere in France, letter of [November] 4, 1917.

10 Hooper, Somewhere in France, letter of November [14], 1917.

11 Campbell, Murton Llewellyn, diary entry for November 19, 1917.

12 I have not been able to locate an R.A.F. service record for Lawton, which, if it exists, might provide this information.

13 Deetjen, diary entry for February 23, 1918.

14 Munsell, “Air Service History,” p. 197 (12).

15 Cablegrams 782-S and 1046-R.

16 McAndrew, “Special Orders No. 205”; Biddle, “Special Orders No. 35” provides both the date and the location.

17 On Lawton’s assignment to 2 A.S.D. and subsequently to No. 209, see his casualty form, “Lieut. Bradley Cleaver Lawton USAS.” The entry for him on p. 197 (12) of Munsell’s “Air Service History” has him posted to the “R.A.F. & 209″ on May 11, 1918. On 2 A.S.D. (2 Aeroplane Supply Depot) and its locations, see Dye, The Bridge to Airpower, p. 179.

18 Skelton, “Frank A. Dixon and the 17th Aero Sqdn.,” p. 156.

19 Dixon kept two nearly identical group photos of 209 Squadron officers that include himself, Armstrong, and Lawton. See Reed and Roland, Camel Drivers, p. 45 and Jones, “As I Remember,” p. 38.

20 Here and in the subsequent description of Lawton’s period with No. 209, information is taken from No. 209 Squadron Record Book (RFC/RAF).

21 On 2 A.I. and its location, see mickdavis’s contribution to “Lieutenant Allen Denison.”

22 See “2nd Lieut. Lionel Frank Lomas.” W.E.A. is apparently not a widely used abbreviation; it perhaps stands for “working enemy aircraft” (i.e., observation planes) or “wireless enemy aircraft/alert.” See “RAF abbreviation ‘W.E.A.’—special mission intercepting.”

23 C. N. Jones, “As I Remember,” p. 38.

24 See the casualty forms: “Lieut. Bradley Cleaver Lawton USAS,” “2nd Lieut. Lionel Frank Lomas,” “2nd Lieut. Hubert Mason,” “Lieut. Mark Adamson Harker,” and “Captain Oliver Colin Le Boutillier.” Based on a different source, (Casualty Return for the Month of June [209 Squadron]), which I have not seen, Hudson, In Clouds of Glory, pp. 37 and 237, concludes that Le Boutillier was wounded on June 14, 1918.

25 See the entries on his casualty form, “Lieut. Bradley Cleaver Lawton USAS.”

26 Clapp, A History of the 17th Aero Squadron, p. 156, gives June 26, 1918 as the arrival date for the four men. Munsell, “Air Service History,” indicates, p. 149 (9), that Desson and Dixon arrived June 25, 1918, pp. 192 (7) and 197 (12) that Armstrong and Lawton arrived June 26, 1918.

27 Reed and Roland, Camel Drivers, p. 29.

28 See Clapp, A History of the 17th Aero Squadron, p. 24; Reed and Roland, Camel Drivers, pp. 35 and 40.

29 On the accident, see Clapp, A History of the 17th Aero Squadron, p. 156, and Reed and Roland, Camel Drivers, pp. 37–38. Sturtivant and Page, The Camel File, provides the number of Lawton’s plane; the entry their describes Lawton as uninjured—perhaps the injuries seemed slight initially; Reed and Roland indicate that Lawton did his best to ignore them for a time.

30 War Department, Office of the Quartermaster General, Army Transport Service, Lists of Incoming Passengers, 1917 – 1938, Passenger list for casual officers, Air Service, on Mauretania. Among those on board was Theose Elwyn Tillinghast, who had been in the 17th with Lawton. Given Lawton’s father’s middle name, some family connection seems likely, but I have not been able to trace one.

31 See “Alumni Who’s Who,” p. 90, and Ancestry.com, U.S., World War II Draft Registration Cards, 1942, record for Bradley Cleaver Lawton.