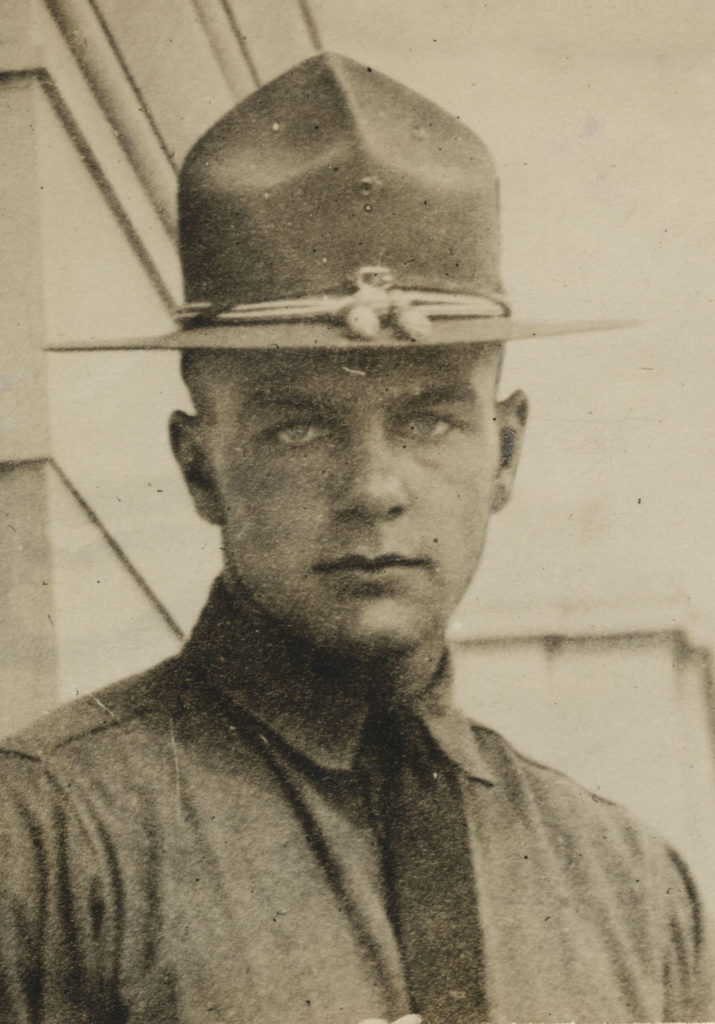

(Medical Lake, Washington, January 6, 1898 [?] – Staten Island, New York, April 4, 1967)1

Plattsburg, M.I.T., Oxford, Grantham ✯ Flight training, ferry pilot ✯ France & No. 73 Squadron R.A.F. at Beauvois ✯ No. 73 at Fouquerolles ✯ June 10, 1918, and after

Leyson’s great-grandfather, John Leyson, was a collier in Wales. He, his wife, and their oldest son emigrated to Pennsylvania in the 1830s, eventually settling in Wisconsin and taking up farming. Mining, however, was in the blood, and at least one of John Leyson’s sons, David Bassett Leyson, made a living at it, moving to Nevada and then Washington (state). His son in turn, Leyson’s namesake and father, also started out in mining in eastern Washington.2 There, in Medical Lake, not far from Spokane, in February 1897 Burr Watkins Leyson, Sr., married Catherine (Kittie) Virgin, descendant of a family with deep New England roots.3

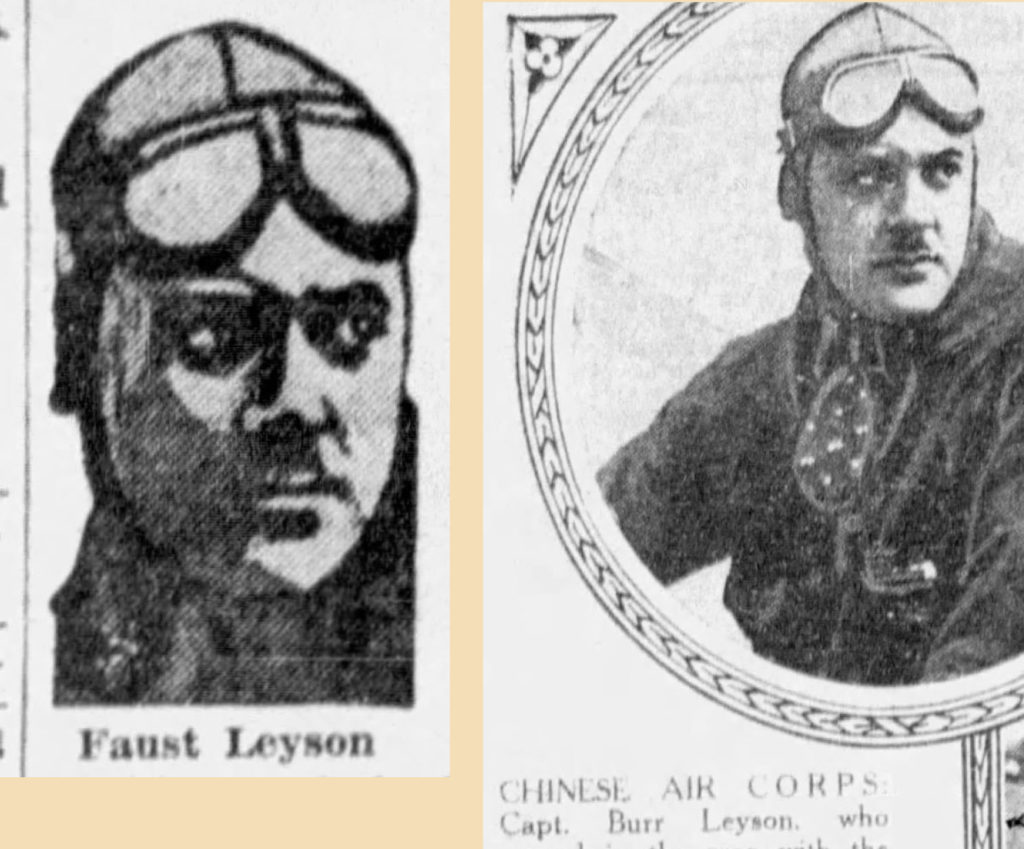

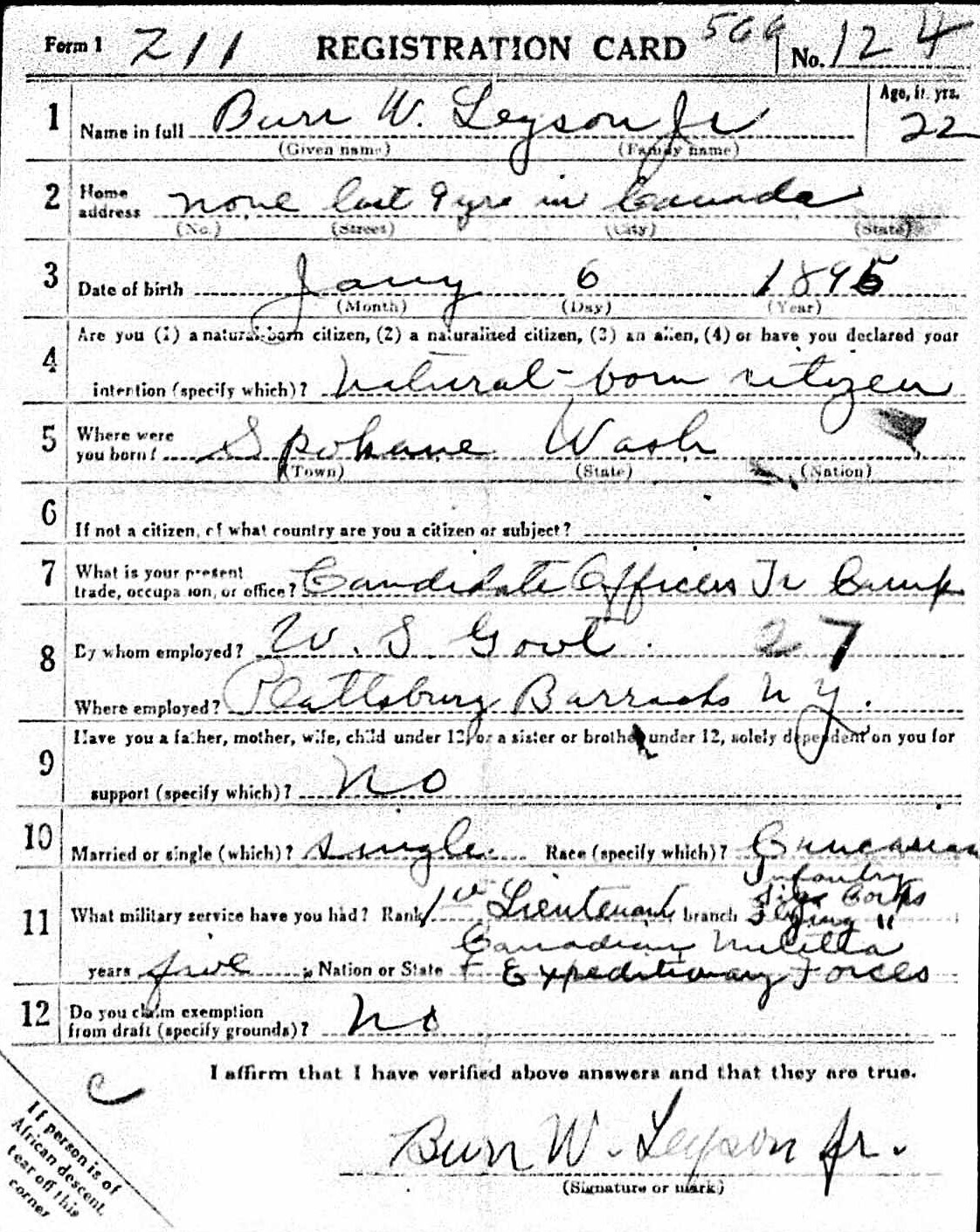

Records related to Leyson’s early years and immediate family are confusing, but I believe I have reached an accurate understanding of them. Leyson himself, on his draft registration forms, gave his date of birth as January 6, 1895.4 It is possible, of course, that his birth preceded his parents’ well documented marriage date. It is curious, however, that his name does not appear beneath those of his parents on either the 1900 U.S. census or the 1911 Canadian census. Instead, there is listed a son, Faust, born in 1898.5 Said Faust then largely disappears from the public record, except when he appears in a 1928 newspaper article announcing his plan to assist Chinese aviation, and again in 1940, when he is listed as the informant on his mother’s death certificate.6 There are also articles from 1928 with photos of Burr Watkins Leyson, Jr., announcing his plan to assist the Chinese, and in one instance his photo and that of Faust are identical.7

This and other evidence (their both being listed as residing in Flushing, New York, in the early 1940s, for example) has led me to conclude that Burr, Jr., and Faust were the same person. Perhaps, as in many families in which father and son share a name, a nickname, albeit an unusual one, was chosen to differentiate them. I suspect that Leyson’s year of birth was, in fact, 1898, as recorded for Faust. On passenger lists where Leyson’s age is given, rather than his date of birth, the age correlates to 1898 as the year of birth.8 And Leyson would hardly be the only member of the second Oxford detachment to have described himself on his draft registration form as older than he was, presumably out of concern that he might otherwise be disqualified as too young to serve.

Proceeding on the assumption that Faust and Burr were the same person, it is possible to document his move to Canada in about 1907. It appears that his father, who became superintendent of a mining company in Colbalt, about 250 miles due north of Toronto, made the move in 1906, leaving wife and son to follow. In 1911 the family was residing in Toronto.9 I find no direct documentation of Leyson’s education, but his R.A.F. service record indicates that in 1917 he was a student at the University of Toronto.10 A 1918 article in the Boston Globe states that he had worked as a “correspondent for the Toronto World.”11

Leyson’s draft registration indicates that he served five years in the “Canadian Militia,” in the infantry and the flying corps, and achieved the rank of first lieutenant (this information, if accurate, would better accord with the earlier birth date).

Plattsburg, M.I.T., Oxford, Grantham

By early summer of 1917 Leyson was back in the U.S. and a candidate at the officers training camp at Plattsburg, New York—where, according to a Boston Globe article from 1917, storekeepers were being asked to speak French to the candidates (the town was twenty miles from the border with Quebec).12 Leyson, along with Lloyd Andrews Hamilton, Edward Frank Hollander, and Joseph Ralph Sandford, had been assigned to the training camp’s New England regiment. They, as well as Walter Chalaire from the New York regiment and Edward Addison Griffiths from the Brooklyn regiment, were among twenty-five men at Plattsburg selected in July to attend ground school at M.I.T.13

The 1917 Boston Globe article lists home towns for some of the men from the New England regiment bound for M.I.T. For Leyson, the home town is evidently assumed to be Boston, and only a street address is provided: “114 State Street.” This contact address accompanied Leyson for the next two years and gave rise to some puzzlement (“He is not known at 114 State Street”14). His father’s draft card—forty-four years old in 1918, he was obliged to participate in the third registration in September of that year—clarifies the issue.15 The senior Leyson had moved to Massachusetts and was living in Winthrop while working as a mining engineer for Charlemont Pyrites Company, whose offices were at 114 State Street in Boston. In American and British records, Leyson names his father as his contact person and supplies this address, perhaps regarding it as more permanent than any home address he could provide for his peripatetic parent—who would, indeed, soon relocate to Montana.

Leyson and his five comrades from Plattsburg successfully completed their ground school training at M.I.T. on August 25, 1917.16 The graduation roster lists Leyson as “B. W. deB. Leyson,” which his R.A.F. service record expands to “Burr Watkin [sic] De Bassette Leyson.” The name “Bassett” appears as a given or middle name frequently in Leyson’s family, probably in remembrance of his father’s maternal grandmother, Catherine Morgans Bassett. In later life Leyson generally went by “Burr W. Leyson.”

A third of the men in Leyson’s M.I.T. ground school class of thirty-three chose or were chosen to continue their training in Italy, and these included Leyson, Chalaire, Griffiths, Hamilton, Hollander, and Sandford—who perhaps now wished there had been Italian shopkeepers at Plattsburg. 17 But language lessons would soon be provided. The 150 members of the “Italian detachment” sailed from New York on the Carmania on September 18, 1917, and, after a stopover at Halifax to join a convoy, began the Atlantic crossing. Among those on board was Fiorello La Guardia, who took it upon himself to offer Italian classes to the men. After an uneventful voyage, the Carmania docked at Liverpool on October 2, 1917. Almost immediately on arrival, the detachment learned that they would not be going to Italy but would instead remain in England and attend ground school (again) at the Royal Flying Corps’s No. 2 School of Military Aeronautics. La Guardia left them and continued on to Italy and Foggia, where he would oversee the training of other American aviators in the making.

After a month at Oxford, twenty members of the detachment were selected to begin flying training at Stamford in southwest Lincolnshire, while the remaining 130, including Leyson, travelled farther north to Grantham to attend machine gun school at Harrowby Camp. They were in a holding pattern because there were not yet openings at training squadrons to accommodate them. A group of fifty men were able to set off for training squadrons on November 19, 1917, but Leyson was among those who continued machine gun training through Thanksgiving and the end of November at Grantham, where he shared a hut (sleeping quarters) with George Atherson Brader, Wendell Ellison Borncamp, Ralf Andrews Crookston, Lloyd Ludwig, Clark Brockway Nicholl, Donald Swett Poler, Hilary Baker Rex, and Donald Andrew Wilson.18

Flight training, ferry pilot

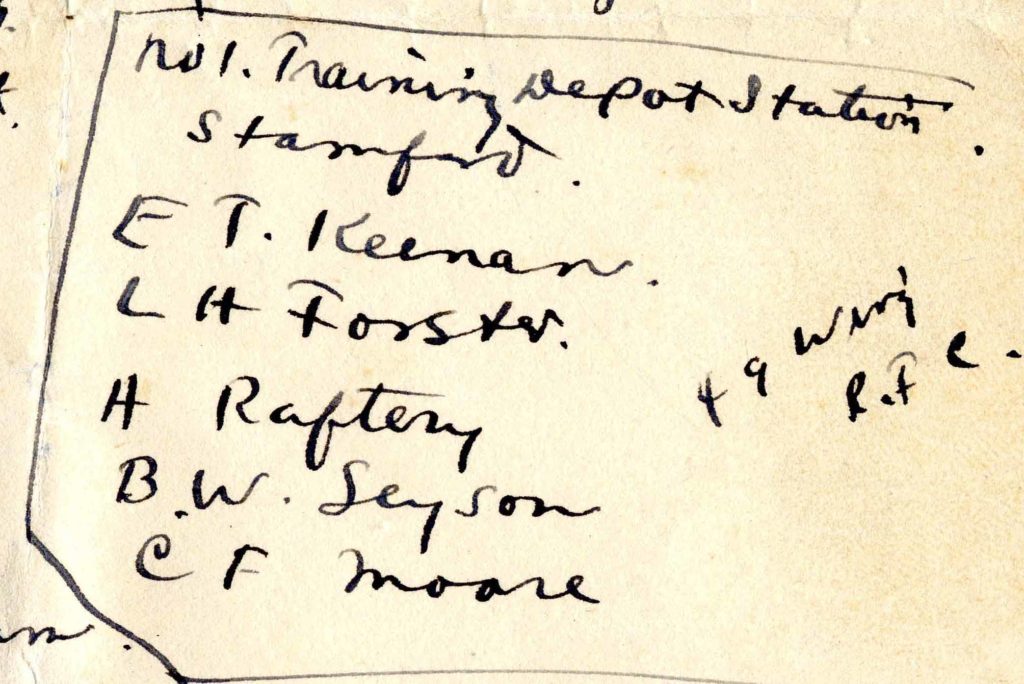

Finally, on December 3, 1917, the remaining men were posted to flying schools. According to a list drawn up by second Oxford detachment member Fremont Cutler Foss, Leyson was one of five men posted this day to No. 1 Training Depot Station at Stamford, thus joining the twenty who had gone there in early November. The others in Leyson’s group were Linn Humphrey Forster, Edmond Thomas Keenan, Charles Francis Moore, and John Howard Raftery.19 They probably would have begun their flying training at Stamford on JN-4s and Avros.

The only other information I have been able to find about Leyson’s training comes from his sketchy R.A.F. service record, which indicates that at some point he was assigned to No. 3 Training Depot Station. No. 3 T.D.S., located at Lopcombe Corner, a few miles northeast of Salisbury, served as a training school for single-seat fighters; Leyson presumably trained there on Sopwith Camels.20 By mid-March he had flown enough hours and passed enough tests to qualify for his commission as a first lieutenant. Pershing forwarded the recommendation to Washington, D.C., in a cable dated March 20, 1918.21 The confirming cable was dated April 2, 1918, the day after the Royal Flying Corps merged with the Royal Navy Air Service to form the Royal Air Force.22

When Leyson had completed his training, he served for a time as a ferry pilot. In a letter to his father that was published in the Boston Globe he described this work:

I’m working d—d hard now, on the go all day and night. I’m flying machines to France, over the channel. Ferrying, they call it. I am flying scouts over. We depart to London, take the first train out to any place they have machines ready to go over, get there, fly them as far as we can the same day (we usually start at dusk), land at some town and away at dawn to a southern port, get refilled and away to France. There we deliver the bus to a squadron and fly an old one back, or take a boat. Then to London and away on another job. Live in a haversack and in the air, sleep when and where we can. S’nice! . . . I’ve had a look at the war also. I went over the lines a day or so ago. It is not regulation, but—. And up came some archie, woof—woof! And home went little Willie! I passed the place I was supposed to land at and saw the lines away ahead, so I decided to look at the war. I did and it looks quite interesting.23

I’m working d—d hard now, on the go all day and night. I’m flying machines to France, over the channel. Ferrying, they call it. I am flying scouts over. We depart to London, take the first train out to any place they have machines ready to go over, get there, fly them as far as we can the same day (we usually start at dusk), land at some town and away at dawn to a southern port, get refilled and away to France. There we deliver the bus to a squadron and fly an old one back, or take a boat. Then to London and away on another job. Live in a haversack and in the air, sleep when and where we can. S’nice! . . . I’ve had a look at the war also. I went over the lines a day or so ago. It is not regulation, but—. And up came some archie, woof—woof! And home went little Willie! I passed the place I was supposed to land at and saw the lines away ahead, so I decided to look at the war. I did and it looks quite interesting.23

The transcriptions of the letter provided by the Boston Globe do not indicate when it was written, but Leyson remarks that “I’m ferrying for a week or so and then away to a squadron at the front. I’m going to get busy soon.” Probably wary of the censor, he does not name the plane that he anticipates flying at the front, but says of what was evidently the Sopwith Camel that “no bus [plane] can fight it successfully at all as it turns too quickly. She has over 12–horsepower in her. You can imagine her speed from that.” He notes that “her favorite stunt is spinning into the ground” and that many are wary of the plane because of that. “[B]ut I think it is all rot. I have had over 50 hours on them and all I have broken is a tail skid taxying out to take off. Yesterday I made a posh (good) landing in a 40-mile wind. Everybody thought I was sure to crash!”

France and No. 73 Squadron R.A.F. at Beauvois

On May 11, 1918, Leyson was posted to No. 2 A.S.D., i.e., sent to France, probably to a pilots pool near Berck-sur-Mer south of Boulogne, to await orders to join a squadron.24 On May 17, 1918, he was assigned to No. 73 Squadron R.A.F., along with Charles William Harold Douglass, also of the second Oxford detachment, as well as Richard Mortimer of the first Oxford detachment.25 Another American, Harold Clement Hayes, was assigned to 73 the same day, as was the Yorkshire-born Canadian Thomas Geoffrey Drew-Brook; another American, Roland Dudley Doane was assigned the next day.26 Don Minterne, in his history of the squadron, writes that around this time an “order had been promulgated that all Camel squadrons would have an increase in establishment to 27 pilots and 25 aircraft,” (up apparently from twenty-one and eighteen), and the result was this influx of pilots from across the pond.27

No. 73 was stationed at Beauvois, about thirty miles inland from the coast, due east of Berck. It had moved to Beauvois, with brief intermediate stops, after being driven from Champien during the initial phase of the German Spring Offensive in the latter part of March 1918. Rather than being part of a brigade attached to a particular British army, No. 73 Squadron was among those in the 9th (Day) Wing of IX Brigade, which served directly under R.A.F. headquarters in France. R.A.F. HQ could send these squadrons wherever they were most needed.28

On the first three days after his arrival at Beauvois, Leyson tried out different Camels and familiarized himself with the squadron and the area.29 By the evening of May 20, 1918, he had evidently settled on Camel D1963, and he participated in his first line patrol, taking off at 6:50 p.m. and returning at 8:00. Maurice Le Blanc-Smith, B-flight commander, led this mission, which consisted of the six men new to 73 (Leyson, Douglass, Mortimer, Hayes, Drew-Brook, and Doane) as well as Bengal, India-born Keith William Allardyce Symons, who had been posted to 73 on May 8, 1918.30

The next day, May 21, 1918, just four days after arriving at 73, Leyson participated in his first offensive patrol. It was no cakewalk. At 5:30 p.m. six planes took off, followed immediately at 5:35 by five more. If I interpret the record book entries correctly, William Henry Hubbard and Maurice Le Blanc-Smith—flight commanders of C and B flights respectively—each led a flight of three planes, with Geoffrey Arthur Henzell Pidcock, A flight commander, following them with a flight of five. Leyson—who later typically flew with Smith and B flight—appears to have been with Pidcock on this mission. About an hour after leaving the aerodrome the formation was south of Armentières (which had been taken by the Germans during the Lys Offensive in April); they were about thirty miles east northeast of Beauvois. Hubbard, Gavin Lynedoch Graham, and Gerald Pilditch each reported encountering and firing at a formation of three Fokker triplanes. Hubbard and Graham each reported having destroyed a Fokker at near Wavrin and Wingles, respectively, and Pilditch reported a Fokker driven down out of control at near Laventie. Le Blanc-Smith and Albert Vernon Gallie reported firing at a formation of six Fokker triplanes over the Bois-du-Biez, south of Neuve Chappelle, without decisive results. Finally, Pidcock reported engaging with two Fokker triplanes and an Albatros scout southwest of Lille without decisive results. With the exception of Alexander McConnell-Wood, who had engine trouble, Pidcock’s flight, including Leyson, returned to the aerodrome at 8:00 p.m., having been in the air nearly two and a half hours.

The pilots of No. 73 Squadron flew no patrols the next day, but the morning of May 23, 1918, sixteen of their planes set out in three flights (six, six, and four) on an offensive patrol. The record book does not indicate what the objective was, but C flight, led by Hubbard, reported firing at troops in Ichtegem northeast of Diksmuide, thus about sixty miles northeast of Beauvois and a good thirty-five miles north of where they had encountered enemy aircraft on the patrol of May 21, 1918. Both second Oxford detachment pilots, Douglass and Leyson, took part in this mission, and both encountered difficulties on their return. Douglass, in Pidcock’s A flight, got lost and landed at “Clairmaris,” presumably Clairmarais, about thirty miles north of Beauvois. Leyson, in Smith’s B flight, apparently flying D1918, put down somewhat closer to home, at Maisoncelle, a few miles northwest of Beauvois. Hubbard is reported as that evening “bringing [D1918] from forced-landing,” but there is no indication what prompted the landing.

Rain meant no flying the next day, and May 25 and 26, 1918, were occupied with practice and test flights. On May 27, 1918, the planes of No. 73 Squadron set out on an offensive patrol around midday, now at full strength in three flights of six planes each. Leyson, in Le Blanc-Smith’s B flight, was again flying Camel D1963. Their mission this time apparently took them due east; on this otherwise uneventful patrol they reported seeing three Albatros aircraft leaving the Douai aerodrome. The next day’s mission was labelled an “Offensive Patrol,” but it evidently involved ground strafing. In the remarks column in the record book after the names of several pilots, including Leyson’s, it is noted that they fired “r[oun]ds. into Merville,” a town just inside the territory captured by the Germans during the Lys Offensive in April and not far from where Leyson had flown on his first patrol on May 21, 1918.

Leyson did not participate in 73’s next offensive patrol on May 30, 1918, but flew the next four patrols: two on May 31, and one each on June 1 and 2, 1918. Although enemy aircraft were sighted on some of these patrols, there were no combats. On his eighth offensive patrol, on June 2, 1918, Leyson “forced landed” D1923 at Abbeville; there is no indication of what difficulty he had encountered, nor when he rejoined the squadron, but he was back with them in D1923 on June 4, 1918, for a line patrol.

With No. 73 at Fouquerolles

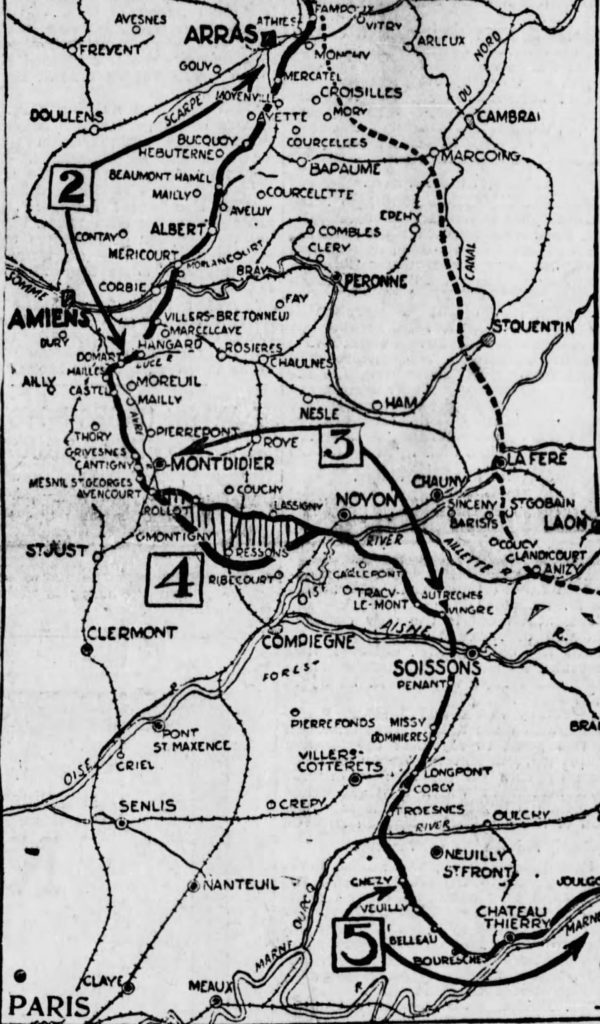

This reappearance would have been a bit more involved than at first appears, for on the preceding day (June 3, 1918) the squadron had relocated from Beauvois to Fouquerolles near Beauvais, seventy miles to the south. The French and British were aware that the next phase of the German Spring Offensive would take place in early June between Montdidier and Noyon, and IX Brigade R.A.F. sent most of its squadrons, including 73, to this front in anticipation of the German attack. The sixteen-plane strong line patrol in which Leyson participated on June 4, 1918, was thus No. 73 Squadron’s introduction to this new area.

At 7:00 the next morning (June 5, 1918), Le Blanc-Smith led B flight, including Leyson, on an offensive patrol and encountered a formation of 4 Albatros aircraft northeast of Noyon; they were “engaged and driven down.” Both A and B flights took part in an apparently uneventful offensive patrol in the afternoon; this was Leyson’s tenth offensive patrol. He did not fly with B flight and Le Blanc-Smith the next morning when the flight accounted for two enemy airplanes, but did fly Camel D6592 with Pidcock’s A flight when A and C flight made an offensive patrol in the late afternoon of that day. The twelve planes apparently crossed the lines near Montdidier and flew northeast well into enemy-held territory to Roye. East of Roye, near Champien (where No. 73 Squadron had previously been stationed), Hubbard reported encountering three formations of enemy planes flying one above the other at ten, fourteen, and seventeen thousand feet; he led C flight in an attack on the lowest formation and was able to drive one down out of control. (It is perhaps of interest that in the remarks column of the record book, Hubbard describes encountering Pfalz aircraft, but in his combat report refers to Fokker biplanes, indicating the difficulty of distinguishing types of plane under combat conditions.31) All planes from A and C flight arrived back at Fouquerolles just before 6:00 p.m., having been in the air nearly two hours.

It appears that the morning of June 7, 1918, Leyson was once again flying Camel D1963, testing it.32 He was evidently satisfied, for soon thereafter he took off in it as part of an offensive patrol made up of B and C flights. They sighted twenty-seven enemy scout planes north of Roye and “dived repeatedly at them and drove them away from the bombing machines, but were unable to close”; the planes of No. 73 Squadron were evidently serving as escort for a formation of bombers, probably for the DH-4s of No. 27 Squadron—the No. 73 Squadron record book indicates “E.A. engaged and brought down out of control” by Hubbard, “confirmed by No. 27 Squadron.”33 Despite having tested his plane, Leyson’s D1963 was one of four, possibly five, planes that experienced engine trouble on this mission. On his way back he was forced to land at Etouy, about seven miles short of Fouquerolles.

Leyson did not take part in the one offensive patrol flown by No. 73 on June 8, 1918, but was one of seventeen off the ground on an offensive patrol (Leyson’s thirteenth) at 5:15 a.m. on June 9, 1918, the opening day of the Montdidier-Noyon Offensive; all planes returned an hour and fifty-five minutes later with, rather surprisingly, “nothing to report.” That afternoon, however, the pilots of No. 73 Squadron began very dangerous work. H. A. Jones, in an account the R.A.F. during this period, describes their activity: “The IX Brigade was employed during the three days of the main battle on low-flying attacks, during which a total of sixteen tons of bombs were dropped and 120,000 rounds of machine-gun ammunition were fired. The reports of the pilots reveal that targets of troops and transport were plentiful, and it would appear certain that heavy toll was taken.”34 Thus the Camels of No. 73 Squadron, designed for high, agile, fast flying, were repurposed as bombers and low-flying machine-gunners. Shortly after noon on June 9, 1918, No. 73 Squadron began sending out formations made up of three planes each every half hour, flying towards the Matz River, west of Noyon, where German troops were pushing forward. Leyson, with Le Blanc-Smith and Gallie, took off in the second group at 12:35. The squadron record book records of him: “100 rds. fired on troops and transport N. of Ricquebourg and 800 rds. on road N. of Orvillers-Sorel”; for some unexplained reason he returned more than an hour later than Le Blanc-Smith and Gallie. Testimony to the danger of this work was Reginald Arthur Baring’s failure to return from the next to last group of three to set out, and the “direct hit from A.A. fire” sustained by Jenkinson’s D6592 (which Leyson had flown on June 6, 1918).35 Jenkinson, unhurt, but in a machine turned upside down, managed to right the plane and glide back over the lines.

June 10, 1918, and after

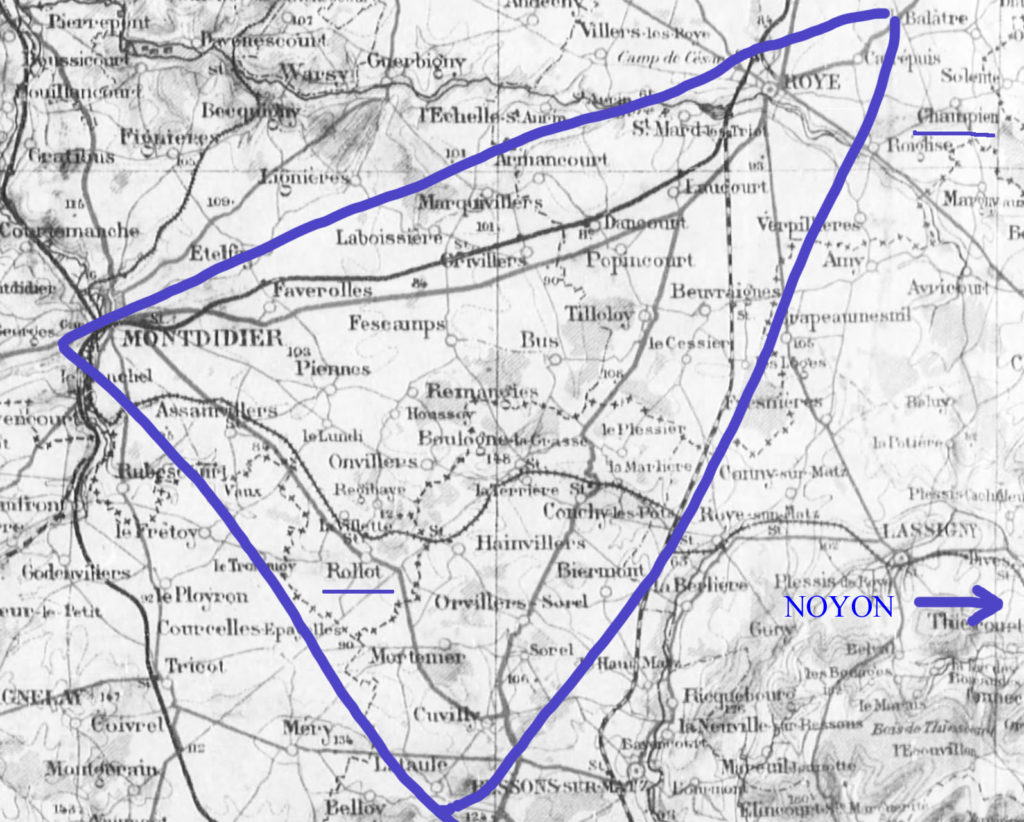

Ground strafing missions in teams of two, three, or four planes recommenced the next morning (June 10, 1918), with the first team setting out at 4:05 a.m. The targets were troops, transport, and ground artillery in the triangle roughly defined by Montdidier, Roye, and Cuvilly. Leyson and Canadian John Haworth Drewry were the fourth team from 73; they took off at 6:00 a.m. After firing at troops, Drewry reported sighting twelve Albatros scouts east of Rollot at 7 a.m. Leyson, meanwhile, in Camel D1963, was “last seen attach [sic] himself to SE formation under control”—presumably planes from either No. 32 Squadron R.A.F. or No. 2 Squadron A.F.C.36 Shortly thereafter, however, according to the relevant entry in Trevor Henshaw’s The Sky Their Battlefield II, “tanks and controls shot up, seen go down ooc [out of control] over Rollot near Montdidier around 7am.” The 73 Squadron record book entry reads: “Not yet returned,” but D1963 was “struck off charge” that same day.37

Word evidently got back to the British or the Americans relatively quickly that Leyson had survived and been taken prisoner, for the first public announcement regarding him that I have found, a story datelined Washington, D.C., July 1, 1918, lists him not as missing, but as a P.O.W.38 By this date, according to the sketchy account Leyson later provided, he was in Karlsruhe in Baden, having been taken initially from Rollot northeast about twenty miles to Ham, then to St. Quentin, and then to Fresnoy-le-Grand; his account notes “pilot shot in right foot.”39 From Fresnoy he was transferred the considerable distance to Rastatt (Baden), and thence the short distance to Karlsruhe. At Karlsruhe a local photographer took a group photo of six American officers that was later forwarded to the parents of one of the men.39a Leyson appears in it, standing at the back, with no apparent sign of discomfort from his wound. He evidently remained only a few days at Karlsruhe before being transferred, according to his account, on July 5, 1918, to Landshut in Bavaria. A number of photos were taken at Landshut of American prisoners of war, and at least one includes Leyson, as well as James Norman Hall, Zenos Ramsey Miller, and George Wright Puryear; the latter three kept copies. From Landshut Leyson was moved to Bad Aibling and then to Ingolstadt (both in Bavaria). The day after the armistice, he was in “Wultzburg”—presumably the P.O.W. camp at Würzburg. His account continues: “November 25, 1918, evaded guards at camp, came out on train as civilian to Lindav [sic; sc. Lindau?]. Passed into Switzerland, treated excellently by Swiss Officers.” Sometime after the war, Zenos Miller and Leyson ran into one another and talked over “the weary days in the German prison camp”—it must indeed have been a very tedious five plus months for Leyson.40

Leyson closes his account by noting that on November 29, 1918, he “reported to Schelles [sic; sc. Chelles], H. Q. Fourtieth Div. Replacement Depot.” Apparently from this depot east of Paris he was posted to the U.S. 41st Aero Squadron on January 15, 1919.41 The 41st Aero Squadron was assigned to the 5th Pursuit Group, which in turn was part of the recently created American Second Army—whose purpose had been erased by the end of the war; it was demobilized at the beginning of April 1919. The Fifth Pursuit Group, however, including the 41st Aero Squadron, was transferred at this time to the Third Army Air Service and was ordered to Koblenz, where it remained as part of the Army of Occupation until being demobilized in May of 1919. At some point during this period of post-war service, Leyson was promoted to captain. Captain Burr W. Leyson, Jr., of the 41st Aero travelled back to the U.S. on the S. S. Cap Finistere, arriving at Hoboken on July 13, 1919, after a ten day voyage.42

Leyson continued flying, entering competitions and working as an air mail pilot.43 As far as I can tell, his plan, touted in newspapers in 1928, “to take complete charge of the air forces of the Chinese Nationalist armies” did not materialize: I find no indication of his travelling to China.44 Possibly the story was newspaper hype connected to pictures taken by photographer Leslie Jones of Leyson with a Chinese aviator at the East Boston Airport in April 1928.45 Leyson also continued writing, publishing stories in Boys Life and in the late 1930s establishing a relationship with the publisher E. P. Dutton, for whom he wrote numerous books.

mrsmcq April 26, 2019

Notes

(For complete bibliographic entries, please consult the list of works and web pages cited.)

1 Leyson’s place of birth is taken from Ancestry.com, U.S., World War II Draft Registration Cards, 1942, record for Burr Watkin [sic] Leyson. On his date of birth, see below. Information about his death is taken from the an obituary on p. 13 of the Staten Island Advance for April 7, 1967, transcribed at Del Priore, “Capt Burr Watkins Leyson, Jr.” The photo, originally from The Boston Globe, is from a collection of World War I Soldier Photographs in the State Library of Massachusetts, now digitized at their website (https://archives.lib.state.ma.us). See below, where the photo is reproduced in “Breezy Letter from Lieut Leyson, Aviator.”

2 On Leyson’s paternal descent, see records available at Ancestry.com and at Familysearch.org.

3 See Ancestry.com, Washington, Marriage Records, 1854-2013, record for B W Leyson. On the Virgin family, see Hughes and Munsell, American Ancestry, vol. 9, p. 64, and Lapham, History of Rumford, Oxford County, Maine, p. 409; these accounts of the family differ in some details.

4 Ancestry.com, U.S., World War I Draft Registration Cards, 1917–1918, record for Burr W Leyson Jr. “1895” is clearly written on his World War II registration form (cited above); on his World War I form, the 1895 has been changed to 1896—or vice versa.

5 See Ancestry.com, 1900 United States Federal Census, record for Faust C Seyson [sic; sc. Leyson], and Ancestry.com, 1911 Census of Canada, record for Faurt [sic; sc. Faust] Leyson.

6 “Toronto Man Air Chief in Chinese Army” and Ancestry.com, Ontario, Canada, Deaths and Deaths Overseas, 1869-1947, record for Katherine Layson [sic; sc. Leyson].

7 See the photo in “Chinese Air Corps.” See also “To Aid China in Air.”

8 See, for example, Ancestry.com, Florida, Passenger Lists, 1898-1963, record for Burr Watkin [sic] Leyson.

9 See the 1911 census cited above, which includes immigration years, and Stokes, “The Cobalt Silver Field, Ontario.—II,” p. 347.

10 The National Archives (UK), Royal Air Force officers’ service records 1918–1919, record for Burr Watkin [sic] De Bassette Leyson.

11 “Breezy Letter from Lieut Leyson, Aviator.”

12 “Brush up on French at Plattsburg Camp.”

13 “Twenty-five Plattsburg Men to Become Aviators.”

14 “Four of our Officers Held in Prison Camps.”

15 Ancestry.com, U.S., World War I Draft Registration Cards, 1917–1918, record for Burr Watkin [sic] Leyson.

16 “Ground School Graduations [for August 25, 1917].”

17 There are thirty-four men listed in “Ground School Graduations [for August 25, 1917],” but William Ludwig Deetjen had, in fact, graduated earlier.

18 Ludwig, diary entry for November 19, 1917.

19 Foss, Papers, “Cadets of Italian Detachment Posted Dec 3rd.”

20 Philpott, The Birth of the Royal Air Force, p. 255.

21 Cablegram 756-S.

22 Cablegram 1028-R.

23 Leyson’s letter was published in The Boston Globe twice, once in a longer version on July 2, 1918 (“Breezy Letter”), and in a shortened version on July 3, 1918 (“Describes ‘Ferrying’ Planes over Channel”).

24 See his R.A.F. casualty form, “Lieut. Burr Watkin [sic] de Bassette Leyson USAS.”

25 Ibid., “Lieut. Charles William Harold Douglass,” and “Lieut. Richard Mortimer U. S. A. F. (USAS).”

26 See their casualty forms: “Lieut. Harold Clement Hayes RAF,” “2nd Lieut., Lieut. Thomas Geoffrey Drew Brook R. A. F General List,” and “2nd Lieut. Roland Dudley Doane RAF.”

27 Minterne, The History of 73 Squadron, p. 7.

28 On the role of IX Brigade, see Callender, War in an Open Cockpit, p. 57, note 3; on the composition of brigades and the role of IX Brigade, see McCluskey, “The Battle of Amiens and the Development of British Air-Land Battle, 1918-45,” pp. 232-33. For the composition of IX Brigade in April 1918, see “RAF IX Brigade Order of Battle April 1918.”

29 See RFC/RAF No. 73 Squadron Record Book; unless otherwise noted, the subsequent description of 73’s and Leyson’s activity is based on the record book. I should note that the copy of the record book I have been able to consult is of poor quality; I have done my best to decipher place names and plane numbers in particular, but may not always have been accurate.

30 See the casualty card, “2nd Lieut., Lieut. Keith William Allardyce Symons.”

31 See Hubbard’s combat report for June 6th, 1918, in RFC/RAF No. 73 Squadron Combat Reports.

32 The plane number is difficult to read, but is almost certainly D1963.

33 I find no combat report for this encounter, and it does not appear on victory lists for Hubbard.

34 The War in the Air, vol. 6, pp. 403–04.

35 Baring’s body was not found; his name is inscribed at the Arras Flying Services Memorial. His loss is especially poignant, as he was the fourth of the five sons of the widowed Amy Baring, née Stamper, to die in the war.

36 Quoted remark is from casualty card, “Leyson, B.W.deB.”

37 Sturtivant and Page, The Camel File.

38 “Four of our Officers Held in Prison Camps.”

39 Presenting the Experiences of Air Service Officers who were Prisoners of War in Germany, p. 179.

39a See “Boston Officer Shown in Group of Captives.”

40 Eddy, In Memory of Zenos Ramsey Miller, p. 52.

41 Sloan, Wings of Honor, p. 429.

42 Ancestry.com, U.S., Army Transport Service, Passenger Lists, 1910-1939, record for Record for Burr W Leyson Jr.

43 See Frattasio, NAS Squantum, p. 125, and description of Leyson in “Radio Program for Today.”

44 “To Aid China in Air.”

45 Leslie Jones, “Harry King, Chinese aviator . . .” and “Chinese aviator Harry Dally King. . . .”