(Fremont, Ohio, January 9, 1892 – Columbus, Ohio, April 3, 1977)1

Training in England ✯ France and No. 20 Squadron R.A.F. ✯ With the A.E.F. and after

Oberst’s paternal grandfather and grandmother came to Ohio in about 1845 from Baden and Switzerland respectively. His mother, née Sarah Lucinda Lobdell, was descended from a Simon Lobdell who emigrated from England to Connecticut in about 1645. Both of Oberst’s grandfathers were farmers in Ohio, as was his father, Michael Oberst. Oberst was the second youngest of eight children, all born in or near Fremont in northern Ohio.2 The year 1912 finds Oberst employed as a “bridge worker” in nearby Toledo.3 The following year, perhaps inspired by the example of his paternal grandfather, who served in both the Mexican–American War and the Civil War, Oberst applied to West Point; he did well on the entrance exams but missed out on being appointed.4 In 1914 he enrolled at Ohio State University, where he served in the military cadet corps.5 He was also working. His draft registration card indicates that in June 1917 he was a civil engineer employed by the Modern Construction Company of Fremont, and his R.A.F. service record indicates that this employment began in 1914.6 Oberst evidently interrupted his studies as well as his work when he successfully applied to the Aviation Section of the Signal Corps. He attended ground school at O.S.U. with the class that graduated September 1, 1917.7

Along with most of his O.S.U. classmates, Oberst chose or was chosen to train in Italy, and he joined the 150 men of the “Italian” or “second Oxford detachment” who sailed to England on the Carmania. They departed New York for Halifax on September 18, 1917, and departed Halifax as part of a convoy for the Atlantic crossing on September 21, 1917. The men of the detachment travelled first class and enjoyed shipboard leisure, including concerts featuring the violinist Albert Spalding, who was on his way to Italy. They also had Italian lessons, taught by Fiorello La Guardia. Once the convoy entered dangerous waters, the men took turns at submarine watch. When the Carmania docked at Liverpool on October 2, 1917, the detachment learned to their initial dismay that they were not to go to Italy, but to remain in England.

The men travelled by rail from Liverpool to Oxford and dined the evening of October 2, 1917, in the Great Hall of Christ Church College at Oxford University, where the Royal Flying Corps’s No. 2 School of Military Aeronautics at Oxford University was located. They scattered to rooms in various colleges for the night. The next afternoon they were reassigned to either Queen’s College or Christ Church College. Oberst apparently shared a room at Queen’s with Guy Samuel King Wheeler, who had been in the class ahead of his at ground school.8 Instruction, which began October 8, 1917, covered much of the same material that the cadets had studied in the U.S., and they thus did not have to work particularly hard. There was time and opportunity to explore Oxford and the surrounding countryside. Oberst’s fellow detachment member Fremont Cutler Foss recorded in his diary on October 9, 1917, that “After lunch I met Oberst and [Albert Elston] Weaver who asked me to join them and do a little boating on the Thames. So after visiting the canteen we hired a canoe and paddled about 1½ miles up the Thames which is more than beautiful. Oberst took a couple of pictures of cattle and sheep drinking from the stream.” (Weaver had been in the same ground school class as Foss and Oberst at O.S.U.) A few days later, the three men rode bicycles out to the aerodrome at Port Meadow to the northwest of Oxford and had tea at the Trout Inn.9

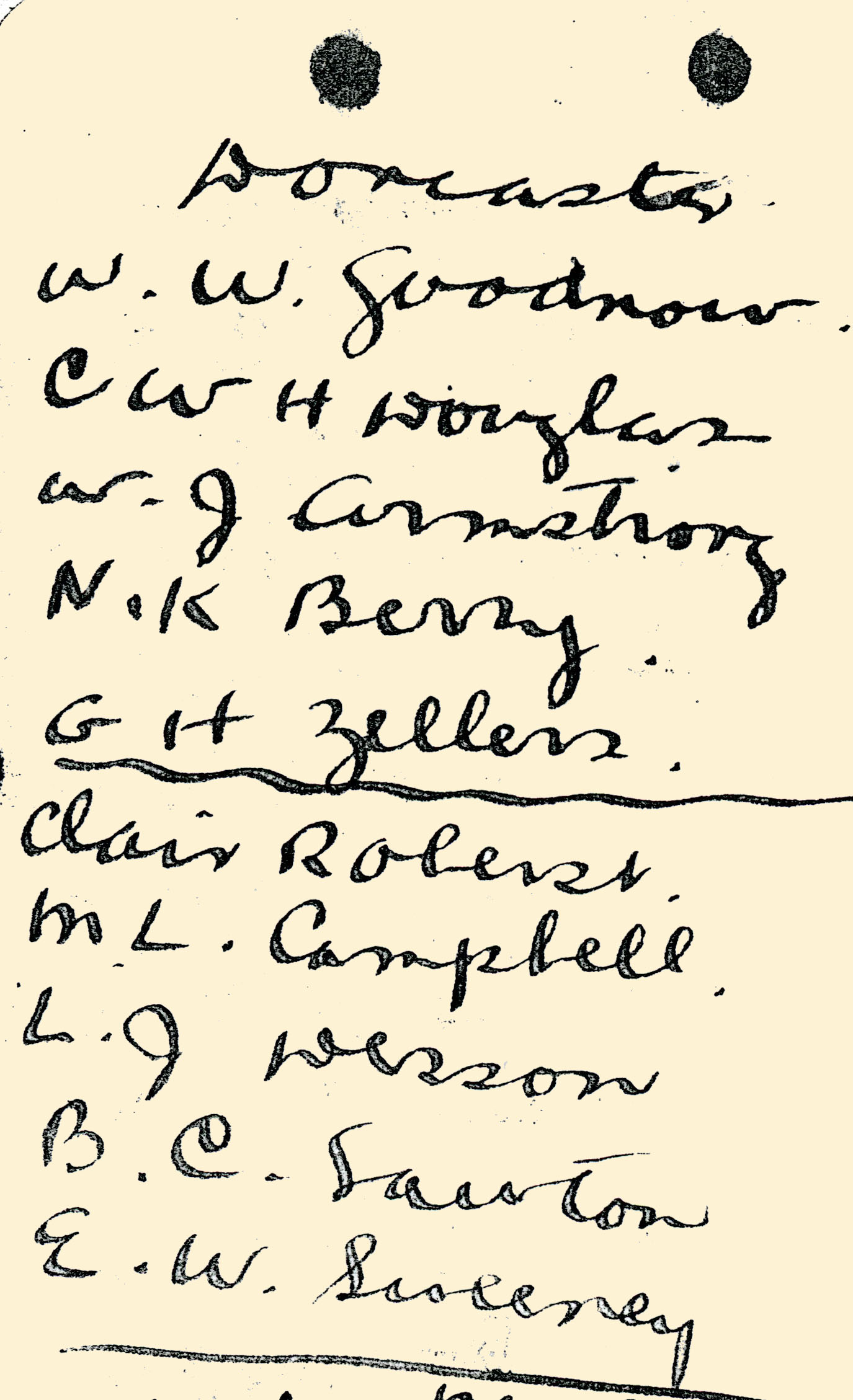

On November 3, 1917, Oberst and most of the rest of the detachment left Oxford to go to machine gun school at Harrowby Camp, near Grantham in Lincolnshire. The course was to be two weeks on the Vickers gun, and then two on the Lewis. However, after the first two weeks it was determined that fifty of the cadets could go to training squadrons, and on November 19, 1917, Oberst and nine others set off for Doncaster in south Yorkshire where Nos. 41 and 49 Training Squadrons were located. Oberst, along with Murton Llewellyn Campbell, Leonard Joseph Desson, Bradley Cleaver Lawton, and Earl William Sweeney, was assigned to No. 49 T.S.10 They received instruction there on Maurice Farman S.11s, “pusher” airplanes (i.e. with the propeller behind the cockpit and engine) much used in R.F.C. elementary training. Bad weather meant the men initially got fewer hours in the air than they would have liked, but, according to Murton Campbell, weather in early December improved. He, however, was bedridden with a cold, and “had to send Oberst . . . to fill my date. Rather a risky business—send a good looking man to meet a girl you never met yourself.”11

I have not found a record of Oberst’s subsequent training, although a brief mention of him in Murton Campbell’s diary for January 26, 1918, suggests Oberst may have been at Spittlegate near Grantham at that time. In any case, Oberst progressed reasonably rapidly, as the recommendation for his commission was forwarded to Washington at the end of February.12 He was placed on active duty on March 30, 1918, at Marske.13 His very sketchy R.A.F. service record includes an apparent reference to “4 A S of A G,” the No. 4 Auxiliary School of Aerial Gunnery at Marske-by-the-Sea in North Yorkshire. It also notes that “Since joining RAF has flown 160 HP AW DH4 Rolls.”14 The note is not dated, but reference to the R.A.F., which came into being on April 1, 1918, suggests that in April and perhaps May 1918, Oberst was training on Armstrong Whitworth FK.8s and on DH.4s, both of which were two-seater aircraft used for bombing and reconnaissance.

France and No. 20 Squadron R.A.F.

Towards the end of May 1918 Oberst was one of a number of second Oxford detachment members who were posted to “2 A.S.D.,” that is to No. 2 Aeroplane Supply Depot south of Boulogne at Rang-du-Fliers, location also of the pilots pool where men awaited R.A.F. squadron assignments.15 In a photo from the second week of June 1918 in the album of second Oxford detachment member John Chadbourn Rorison, Oberst appears in a group of men “on trench detail” at Rang-du-Fliers.16

While most of the men in the photo were soon assigned to R.A.F. squadrons, Oberst went on June 17, 1918, to No. 51 General Hospital at nearby Etaples.17 A casualty card indicates that he had contracted a venereal disease, hardly a rare or surprising occurrence given that the moralistic attitude of both the British and American authorities limited access to prophylatics.18 In that pre-antibiotic era there was no cure, but intensive symptomatic treatment evidently allowed resumption of military service,19 and at the end of July 1918 Oberst was posted to No. 1 A.S.D. at Marquise.20 From there he was assigned on August 10, 1918, to No. 20 Squadron R.A.F.21 At No. 20 he rejoined Sweeney, who had been with him at O.S.U., Doncaster, and No. 2 A.S.D. (George Herbert Zellers, also at O.S.U., Doncaster, and No. 2 A.S.D. with Oberst and Sweeney, had been assigned to No. 20 with Sweeney on June 7, 1918; he had been killed in combat on July 30, 1918.)

No. 20 Squadron was stationed at Boisdinghem, about twenty miles from the Channel, and was equipped with Bristol F2b Fighters. From shortly after its deployment to France in early 1916, No. 20 had been part of 11th (Army) Wing, II Brigade, and thus under the British 2nd Army, whose front stretched north and south of the Ypres Salient. From December 1915, when No. 20 was initially allocated F.E.2b’s, Lewis machine gun equipped two-seaters, the squadron’s remit was dual: reconnaissance and pursuit, and before long it was also tasked with bombing. The squadron’s flexibility continued after the changeover to Bristol Fighters in late summer 1917.22 These two-seater biplanes were initially designed for reconnaissance, but, because of their powerful engines, they were also suited to aerial fighting, and the squadron scored a remarkably high number of combat victories.

The first weeks of August 1918 were comparatively quiet on the 2nd Army Front. The German Spring Offensive had petered out, and around the time Oberst joined No. 20 Squadron, the Allies had opened the Battle of Amiens, shifting war activities to the south. No. 20 Squadron’s record book for 1918 is, unfortunately, no longer extant, and I can thus not trace Oberst’s activities with the squadron in any detail. However, Robert A. Sellwood, in his Winged Sabres, has been able to reconstruct a good deal of the squadron’s activity from a variety of official and private documents.

In August 1918, up until the 14th, No. 20 Squadron conducted largely unopposed offensive patrols and reconnaissance missions along the 2nd Army front, as well as bombing raids on Menin, on railroads around Courtrai, and on Comines. There were encounters with enemy planes on August 14 and 15, 1918, during offensive patrols in the vicinity of Dadizeele and Gheluvelt.23

A week later, on August 21, 1918, following an evening bombing raid on a railway junction at Comines, No. 20 Squadron planes “engaged a formation of 25 enemy scouts of various types” and were then attacked by a formation of seven Fokker biplanes.24 Oberst participated in this mission and briefly recalled the encounter: “In a big mix-up on August 21st, 1918, East of Ypres, my observer got in a good burst at a Fokker biplane, but he was claimed by another machine, which was also firing at him.”25 Over the course of this “mix-up” at least six German planes were shot down, including apparently two Fokker biplanes, one of which may have been the one targeted by Oberst’s unnamed observer.26

Just a few days after this, on August 26, 1918, No. 20 Squadron moved fifty miles due south, to Vignacourt, about ten miles north-northwest of Amiens, essentially switching places with No. 48 Squadron R.A.F., which had suffered from a German bombing raid on its base at Bertangles the night of August 24–25, 1918. No. 20 was now part of V Brigade and attached to the 4th Army, which was advancing eastward towards Peronne.27

Oberst recalled: “Moved down on the Somme Front August 26th, where we found the Huns more plentiful and the Archies getting lots of practice and they picked off my observer on my first trip over the lines.”28 Oberst’s observer was presumably Lawrence Edgar Bradshaw, who was wounded in the neck by anti-aircraft fire during an evening patrol on September 2, 1918.29 After hospitalization in France, Bradshaw was transferred to England in mid-September.30

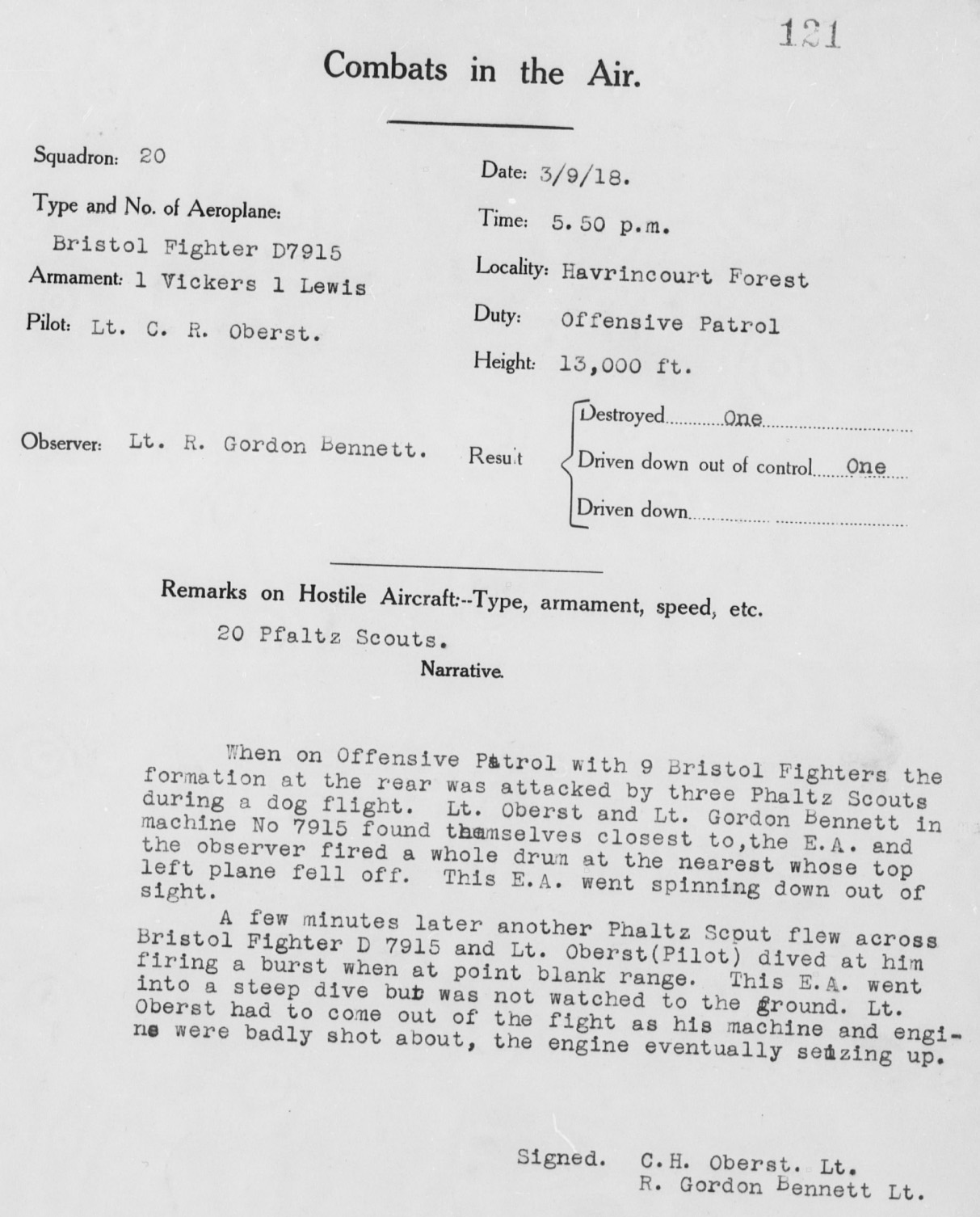

On September 3, 1918, the day after Bradshaw was injured, Oberst flew Bristol Fighter D7915 with observer Richard Gordon Bennett as part of a three plane flight at the rear of a formation of nine planes on an offensive patrol. Near the Bois d’Havrincourt, about forty miles east of Vignacourt and approximately ten miles north of Peronne, the formation was attacked by “a mixed formation of twenty Pfalz and Fokker DVII scouts from Jastas 5 and 36.”31 The rear flight was attacked by three of the Pfalz scouts. Oberst and Bennett “found themselves closest to the E.A. and [Bennett] fired a whole drum at the nearest whose top left plane fell off. This E.A. went spinning down out of sight. A few minutes later another Phaltz [sic] Scout flew across Bristol Fighter D 7915 and Lt. Oberst dived at him firing a burst when at point blank range. This E.A. went into a steep dive but was not watched to the ground.”32 By this time Oberst’s plane was badly damaged, and he was only just able to get it back into Allied territory to land.

Oberst recalled that “On Sept. 5th we had a dog-fight S.E. of Cambrai”33; this was apparently in the afternoon during a “six-strong formation led by Captain [Horace Percy] Lale and Lieutenant [Harold Leslie] Edwards . . . that was attacked from out the clouds by eleven Fokker DVIIs.”34 Oberst goes on to remark that “Patrol got three Huns, but did not claim any of them.”35 This September 5, 1918, patrol is the last mission flown by Oberst of which I have found any record, although he may well have taken part in patrols over the next five days.

On September 10, 1918, first Oxford detachment member Paul Stuart Winslow recorded in his diary that “…orders came through for thirteen of us,” including Oberst, “to report to No. 3 Instructional Center at Issoudun.”36 This they did, and confusion ensued: “When we reported to Major Lamphier, we were told that we were ordered here by mistake, and they did not know what to do with us. . . .”37 Two days later: “[Reed Gresham] Landis, [Duerson] Knight, and Oberst are to be fighting instructors at Field 8.”38

Plans apparently changed yet again; according to a history of the U.S. 25th Aero Squadron, Oberst, along with Rorison, reported to the 25th Aero at Colombey-les-Belles on September 23, 1918.39 The 25th was to be an S.E.5 squadron but did not receive its full complement of planes until well into November; it became nominally operational, thanks to a flight over the lines on November 10, 1918.40 Oberst appears in a photo of officers of the 25th Aero taken on December 7, 1918.

Oberst was able to return to the United States shortly after the war was over. Along with fellow second Oxford detachment members Desson and Conrad Henry Matthiessen, he sailed from St. Nazaire on the U.S.S. Finland on January 31, 1919, arriving at Hoboken on February 14, 1919.41 Oberst returned to his studies at Ohio State University, graduating with a degree in engineering in 1921.42 He went on to specialize in industrial ceramics and founded Industrial Ceramic Products, Inc., an Ohio company that is still in the family.43

mrsmcq May 12, 2021

Notes

(For complete bibliographic entries, please consult the list of works and web pages cited.)

1 For Oberst’s place and date of birth, see Ancestry.com, U.S., World War I Draft Registration Cards, 1917–1918, record for Clair Oberst. On his place and date of death, see “Clair Oberst.” The photo is a detail taken from a group photo of the O.S.U. ground school class of September 1, 1917.

2 On Oberst’s family, see documents available at Ancestry.com. On the Lobdell family, see Lobdell, Simon Lobdell, 1646 of Milford, Conn. and His Descendants.

3 See entry for Oberst in Polk’s Toledo Directory for the Year Commencing July 1912.

4 See “Tiffin Boy High for West Point.”

5 See, for example, The Makio 1914, p. 443.

6 The National Archives (United Kingdom), Royal Air Force officers’ service records 1918–1919, record for Clair Rutherford Oberst.

7 “Ground School Graduations [for September 1, 1917].”

8 Foss, diary entry for October 3, 1917. “Apparently” because the name “Wheeler” is difficult to read.

9 Foss, diary entry for October 13, 1917.

10 Murton Campbell, diary entry for November 19, 1917.

11 Murton Campbell, diary entry for December 4, 1917.

12 Cablegram 657-S.

13 McAndrew, “Special Orders No. 205”; Biddle, “Special Orders No. 35.”

14 The National Archives (United Kingdom), Royal Air Force officers’ service records 1918–1919, record for Clair Rutherford Oberst.

15 “Lieut. Clair Rutherford Oberst USAS + RAF.”

16 Doyle, “War Birds Pictorial,” p. 43, photo 40.

17 See Oberst’s R.A.F. service record cited above. Sellwood, Winged Sabres, Chapter 21, gives June 7, 1918, as Oberst’s date of assignment to No. 20; possibly Oberst was briefly at No. 20 before going to hospital.

18 “Oberst, C.R. (Clair R.).” Holmes, “Venereal Disease,” and Marshall, “The British Army’s fight against Venereal Disease.

19 Marshall, “The British Army’s fight against Venereal Disease.”

20 “Lieut. Clair Rutherford Oberst USAS + RAF.”

21 Ibid.

22 On No. 20 Squadron generally during World War 1, see Chapter One of Roberson’s The History of No. 20 Squadron Royal Flying Corps – Royal Air Force.

23 Sellwood, Winged Sabres, Chapter 23.

24 Great Britain, Royal Air Force, Royal Air Force Communiqués 1918, p. 168; cf. Sellwood, Winged Sabres, Chapter 23.

25 Munsell, “Air Service History,” p. 257 (64).

26 Great Britain, Royal Air Force, Royal Air Force Communiqués 1918, p. 168; cf. Sellwood, Winged Sabres, Chapter 23.

27 Sellwood, Winged Sabres, Chapter 23.

28 Munsell, “Air Service History,” p. 257 (64).

29 Sellwood, Winged Sabres, Chapter 24.

30 The National Archives (United Kingdom), Airmen’s Records, record for Lawrence Edgar Bradshaw.

31 Sellwood, Winged Sabres, Chapter 24.

32 See the combat report on p. 21 of Individual Combat Records of Pilots with R.A.F.

33 Munsell, “Air Service History,” p. 257 (64).

34 Sellwood, Winged Sabres, Chapter 24.

35 Munsell, “Air Service History,” p. 257 (64).

36 “Attached to No. 56: Excerpts from the Diary of Paul S. Winslow,” pp. 319–20.

37 “Attached to No. 56: Excerpts from the Diary of Paul S. Winslow,” p. 320.

38 Ibid.

39 “History of 25th Aero Squadron, (Pursuit),” p. 5.

40 Ibid.

41 War Department, Office of the Quartermaster General, Army Transport Service, Lists of Incoming Passengers, 1917 – 1938, Passenger list for Casual Officers Detachment, on Finland.

42 The Makio 1921, p. 120.

43 “Clair Oberst.”