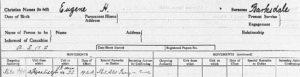

(Goshen Springs, Mississippi, November 5, 1897 [?] – Dayton, Ohio August 11,1926). 1

Barksdale was descended from a family whose roots in Virginia go back to the seventeenth century. An ancestor, Peter Barksdale, fought in the Revolutionary War. Eugene’s grandfather, James Peter Barksdale, left Halifax, Virginia, where his father owned a substantial plantation, to go to Mississippi; he served in the Army of the Confederacy and after the war settled in Goshen Springs.2

Barksdale began studying at Mississippi Agricultural and Mechanical College (as Mississippi State University was then called) in 1914, but left when he was a junior in the spring of 1917 to volunteer for military service. He was initially assigned to infantry training camp at Fort Logan H. Roots (Little Rock, Arkansas), but in July was transferred to aviation.3 He attended ground school at the University of Texas, graduating August 25, 1917.4

There were about thirty-six men in Barksdale’s ground school class. Ten, including Barksdale and his friend Alexander Miguel Roberts, were selected for training in Italy, and these ten were among the 150 men of the “Italian” or “second Oxford detachment” who sailed to England on the Carmania. They left New York September 18, 1917, bound initially for Halifax, where they joined a convoy to make the crossing. Barksdale kept a diary, and the first entry (at least in the transcription available to me) reads in part: “10/2/17 Arrived Liverpool 6 A.M. Landed 9:30 A.M. and found orders changed and we were to go to Oxford Eng. instead of Italy. Some peeved & disappointed bunch we were.”5

Once arrived at Oxford Barksdale roomed with Roberts at Queen’s College, where about 60 of the men from the detachment were housed, with their fellow cadet William Ludwig Deetjen in charge. Ground school, which they were to repeat at Oxford’s School of Military Aeronautics, was to begin on Monday, October 8, 1917, and in the meantime, they were “given the rest of the week to find out the town, etc. & that we did.”6 In Barksdale’s case this included going to a dance on Friday evening; he was evidently a very good and keen dancer, as well as an attractive fellow. References to dances and girls met are scattered throughout his diary entries during his time in England. His social life at Oxford also included tea with Sir William and Lady Osler, with the Morrisons (an otherwise unidentified American family), and at the home of Mrs. Robert Anderson, a widow from Cincinnati living in Oxford.7 Evidence of Barksdale’s more studious side is provided by two publicity photos taken at Oxford, one of cadets at a lecture, one of cadets studying a map; Barksdale appears in both.

On November 3, 1917, Barksdale departed with most of the rest of the detachment for Harrowby Camp, near Grantham in Lincolnshire, to attend machine gun school. He again roomed with Roberts, albeit this time in a hut that housed fifteen men.8 Days were presumably occupied with learning about the Vickers machine gun; in the evenings a play or the cinema and, always, dances. After just over two weeks of this, fifty of the men were selected to go from Grantham to various training squadrons.9 Barksdale and Roberts arrived at Thetford in the afternoon of November 18, 1917, and were allotted a room with fellow second Oxford detachment members Austin Finley Morrison and Glenn Dickenson Wicks; Barksdale was assigned to No. 25 Training Squadron.10

At Thetford, on November 30, 1917, in a “rumpty” (Maurice Farman S.11), Barksdale had his first experience of flying: “Oh but it was a lovely ride tho the air was rather bumpy & we would sometimes drop about 40 feet in a pocket. And in fact it was so bumpy that Capt. Creed (my instructor) would not let me use the joy stick any.” A week later, he watched as the plane, piloted by Gordon Shergold Creed, with his friend Roberts as passenger, crashed and caught fire; Roberts’s injuries were minor, but Creed was hospitalized, and the “machine was a ‘write off’.”11 This was one of many crashes Barksdale witnessed and recorded. On December 19, 1917, Barksdale was ready to fly solo and wrote: “On my first circuit of aerodrome the engine almost conked out . . . I then got in another rumpty & started again. . . . 45 minutes solo & 7 landings with one crash on first day of solo.”

On December 27, 1917, Barksdale left Thetford to go to No. 74 Training Squadron at London Colney, where Roberts had been posted three days previously and where Barksdale soon began flying Avros.12 He witnessed more crashes, including a fatal one on January 11, 1918, when John Harding Greathead “came down with an SE5 in flames & crashed into a tree.” Two weeks later, Barksdale helped ensure a better outcome to an aero accident: “. . . Millar [sic] dived an SE5 into the ground from about 40 or 50 feet. . . . I being the 1st person there found that Millar had been thrown clear from the machine which burst into flames when it hit the ground. His legs, etc. were, however, on fire & I put them out. He was . . . lucky to be alive for any one seeing that crash could not see how it is possible for him to be alive.”13

Days with “lots of flying” alternated with ones of “heavy fog” and no flying. Barksdale apparently witnessed the crash on February 8, 1918, that killed Douglas Quirk Ellis and fatally injured second Oxford detachment member Frederich Joseph Stillman, Jr., as well as the one that killed Lindley Haines DeGarmo of the first Oxford detachment on February 16, 1918. On February 21, 1918, Barksdale found it worth noting that there was “some flying but no serious accidents.” On March 7, 1918, “[w]e were posted to 56 T.S. this morning which merely means going to the other side of the aerodrome.” (No. 74 T.S. was about to become operational and depart for France; its trainees had to be reassigned.) Towards the end of March, Barksdale’s friend Roberts moved on to Scotland, but Barksdale remained at London Colney where, towards the end of April, he progressed from Avros to Sopwith Pups.14

On May 4, 1918, Barksdale crashed a Pup; he describes the incident in his diary:

. . . about 11:30 I got a Pup and I went up for a flip & did not set my aneroid at 0. Was stunting over Shenley [about 2.5 miles south of London Colney]. I spun down to 1300 feet (suming [sic] by aneroid) & then went to roll & after coming out of roll found I was about level with tops of trees, but before [I] could get out over them had lost more height & so caught under carriage in top of trees and came tumbling & crashed down thru trees. The machine turned clear up side down before hitting ground and my belt only saved me. . . . I thinking of fire began a scramble to free myself from belt. . . . People were rushing up from all around and some seemed to be rather disappointed & much surprised that I was not smashed to pieces & even one old fellow had the cheek to tell me I had mashed up his hedge along road way. . . . the machine a complete write off. . . . Went on back to aerodrome in a Tender, told the C.O. about it, signed up some paper and asked for another Pup to take up. Went up and did 45 minutes.

Barksdale’s account of his crash is immediately followed in his diary by his description of the fatal crash of Clarence Horne Fry of the second Oxford detachment the same day.15 Two days later, Barksdale went up in a Spad for the first time: “Did all stunts on Spad on 1st solo & was told it was best exhibition ever shown by 1st soloist on Spad.” On May 9, 1918, he flew in formation with fellow second Oxford detachment member Gilbert Allan Woods and others to Harling Road airfield (in Norfolk), where he “saw a number of our fellows, including Touchstone.” On his return to London Colney, “was told that my tentmate William Winslow Wait of N.Y. had dived a Spad into Elstree Reservoir while firing & was killed.”

On May 17, 1918, Barksdale received orders to go to “No. 2 school of Aerial F and G. Marske by the Sea, Yorkshire”16; he arrived there the next evening and was put in a room with Frank Simpson “Red” Whiting of the first Oxford detachment, and Jarvis Jenness Offutt, “two good room mates.” Two days after his arrival, on May 20, 1918, he wrote: “Two fellows killed on Camels today.”17 Much of his work in the latter part of May involved gunnery practice, although he notes that he did “get two flips on 28/5/18.” Around this time he received his commission—he was in the last large group of men to be appointed first lieutenants—in his case, over a month after Pershing had cabled the recommendation to Washington.18 On June 6, 1918, he was “ordered to France. Order canceled.” This was doubly disappointing, as Roberts cabled him the next day to announce that he (Roberts) had been ordered overseas.19 A few days later, however, things started looking up because he was able to do some flying. He was initially back with Avros, but soon was flying Sopwith Pups. On June 16, 1918, he did practice fighting against a Camel, but ran out of fuel and made a forced landing. Frederick Charles Turner, a second lieutenant from Australia, refueled and took the plane up next, but stalled, crashed, and was killed.20

On June 18, 1918, Barksdale learned that he was to leave Marske the next morning. His R.A.F. service record notes his transfer on June 19, 1918, from Marske to “S.E. Area 40 TS”; an annotation reads: “SE5 Pilot training on Camels.” Barksdale was at 40 Training Squadron at Croydon for a little over two weeks, distinctly unhappy about the R.A.F.’s plan for him. In a diary entry for June 22, 1918, he wrote “they [the adjutant & the C.O. at 40 T.S.] are playing a dirty trick on us by putting us on Camels instead of SE5 like we were supposed to go. A letter from Roberts in France saying he has been posted to our old 74th Squadron. I have just wired him to ‘For gods sake see Capt. Young etc. & help me get over with them.’” Wind and influenza meant that he only flew one day at 40. Discharged from hospital and on sick leave in London, he “went around to see Lt. Dwyer & got transferred back on SE5’s from Camels. Too large for Camels”; the next day (July 10, 1918) he arrived at No. 28 Training Squadron at Hounslow with prospects good for flying S.E.5s. After a week of weather too bad for flying, he finally “had my first flip on SE5 today & think they are lovely.”21 By July 19, 1918, he had “finished my time on SE5’s”; on July 24, 1918, he received orders to depart for France the next morning. He spent a week at the Rang-du-Fliers pilots pool. On July 30, 1918, “a Corporal from 74thSquadron . . . told me that Alex M. Roberts went down in flames over Hunland last Thursday 25/7/18. It was certainly a blow to me. . . .” The next day Barksdale was posted to No. 41 Squadron R.A.F.—the only Oxford detachment man to be posted to that squadron.22

No. 41, which flew S.E.5a’s, was stationed at Conteville-en-Ternois, not far from St. Pol.23 Barksdale had about ten days to learn his way around, and to make a couple of evenings of it with squadron mates at Dieppe, seventy miles to the southwest on the coast.24 He observed the start of the Amiens Offensive on August 8, 1918, in which No. 41 participated. His own participation began with an offensive patrol the afternoon of August 11, 1918, and he flew patrols almost daily from then on.25

On August 13, 1918, he made a forced landing. His diary entry reads: “On early O.P. before we move to Dunkirk. Was shot in my radiator, causing it to lose all water and my engine soon seized up tho I made it back on our side of the lines. Landed O.K. in a wheat field and finally made it to 84th Sqdn. where I phoned to my Sqdn.” He had apparently landed near St. Vaast-en-Chausée, about four miles due west of Bertangles, where No. 84 Squadron was located.26

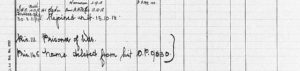

The next day, August 14, 1918, the squadron moved north, not to Dunkirk, but St. Omer, having left behind a plane for Barksdale to use to follow them when he got back from No.84 Squadron.27 Once back with 41, he went over to nearby Clairmarais where No. 74 Squadron was stationed and was buoyed up by the news that “Roberts has lots of chances of merely being a prisoner & not hurt at all.”28 Four days later (August 18, 1918), he received “word today that Alex. Roberts is a prisoner in Germany and unhurt.” Two days after that, Barksdale himself received “word that I have been reported as a prisoner of war & had all my letters stamped as such.”

There is no indication how or why this error occurred, but his R.A.F. service record does, indeed, state that he was a prisoner of war, and American authorities made efforts to investigate, ultimately determining “Eugene H Barksdale, never a prisoner. . . .”29

Patrols continued, and Barksdale’s plane was at least twice hit by “archie” (anti-aircraft fire).30 On August 30, 1918, he led “formation of 5 machines on O[ffensive] P[atrol] & attacked about 12 Fokker biplanes at 14000 feet. I shot one down & crashed and shot another pretty badly but don’t know what happened to it. . . . I found 5 Fokker triplanes & dived on one which went orssy tossy down out of control.”31 Barksdale received official credit for the first biplane.32

Four days later (September 3, 1918), Barksdale wrote in his diary that “our squadron sent down on Avros [sic; sc. Arras?] front. . . . We did two shows & at beginning of last one I got wounded in my right shoulder by archie. It was a bit sore but I finished the patrol by flying with my left hand most of the time. Lt. Turner was last seen spinning towards the ground just after an attack by Hun machines (Fokkers).” The casualty cards for Barksdale and Charles Edgar Turner date the incidents September 2 and September 3, 1918, respectively; Barksdale’s account strongly suggests they were both wounded the same day in the same action, so one of the casualty card dates may be in error.33 After a stay in hospital, Barksdale returned to his squadron, flying again on September 17, 1918.34

On September 24, 1918, according to his diary, Barksdale found himself flying alone over the line and facing enemy aircraft with his engine “working badly & so I realized the only thing to do was go practically straight thru them fighting for life or death. However about time I got started thru them my engine stopped dead & so there was but one thing to do, that is go vertically almost to the ground either by spinning or diving & this I did & thus eluded being hit myself. However, I of course had to land close by and that was in the enemy territory. However on landing in the large shell holes & turning my machine on its back as a result I found a lot of Scotch fellows rushing out to help me out which was a real relief. Then after putting a guard over my machine and taking the watch out I went up to wait at their huts till someone came after me.”

It appears that Barksdale had to land in enemy territory on one other occasion. The transcript of his diary includes a fragmentary entry whose date is unclear: “Was shot down behind Hun lines today during a push but managed to burn machine & return after several hours to our side.”35 This appears to be the incident memorialized in the last dated entry (August 27, 1918) in War Birds: “Barksdale got shot down in an S.E. and landed in German territory but set fire to his plane and got in a shell-hole and covered himself up with dirt. The next morning the British attacked and took that sector. Barksdale said the Scotsman who pulled him out couldn’t speak English any better than the Germans and he thought he was a prisoner at first.”36

Barksdale’s R.A.F. service record indicates he was transferred from No. 41 Squadron on October 13, 1918. His penultimate diary entry, on this date, reads: “(Sunday) withdrawn from R.A.F. & left 41st Sqdn. for Paris.” And the last entry, the next day: “Arrived in Paris.”37

Barksdale’s experiences after leaving the R.A.F. were probably similar to those of Raymond Watts, also of the second Oxford detachment. “About the latter part of October, those of us still with the British were ordered to Issoudun. Here we were to be taught to fly.”38 Once the dust had settled over that misapprehension, plans were made for the 25th Aero Squadron, led by Reed Landis, to obtain S.E.5s in England and to fly them to Toul. There were delays in obtaining the planes, and, although a few pilots and S.E.5s were in Toul on November 10, 1918, “Barksdale and myself were still in Coventry awaiting planes.”39 They celebrated the armistice in London and joined the 25th in Toul soon thereafter.40

Barksdale appears in a group photo of the officers of the 25th Aero taken at there in early December. Returning to the U.S. in February 1919, he shared a stateroom on the Olympic with John Chadbourn Rorison, who had also been with the 25th, and who took photos of Barksdale on board the ship and preserved them in his album.41

After the war, Barksdale returned to the U.S. and obtained a commission in the Army. He served as a test pilot; he died in an air accident.42 Barksdale Air Force Base in Louisiana was named for him.

mrsmcq April 20, 2017

Notes

(For complete bibliographic entries, please consult the list of works and web pages cited.)

1 Barksdale’s draft registration gives his age as 21 and his date of birth as November 5, 1895 (see Ancestry.com, U.S., World War I Draft Registration Cards, 1917-1918, record for Eugene Hoy Barksdale). His 1920 passport application as well as his pilot’s license give November 5, 1896, as his date of birth (see Ancestry.com, U.S. Passport Applications, 1795-1925, record for Eugene H Barksdale; his pilot’s license is reproduced on p. 19 of Bohannon, Prime, and Rigg, Barksdale Air Force Base). Secondary sources usually give November 5, 1897. Cubbison, “‘His Hand on the Stick, His Wings on His Chest’,” p. 345, indicates that Barksdale was born in 1897, but gave an earlier birth year in order to present himself as 21. I believe the original of the portrait photo reproduced here is at the Barksdale Global Power Museum; the image was posted at a now abandoned blog.

2 See Barksdale, Barksdale Family History and Genealogy, passim.

3 See Mississippi Agricultural and Mechanical College, Catalogue 1914–1915. Announcements 1915–1916, p. 232, which lists him as a freshman; and Barksdale, Barksdale Family History and Genealogy, p. 247.

4 “Ground School Graduations [for August 25, 1917].”

5 The typed transcription of Barksdale’s diary covers the period from October 2, 1917, through October 14, 1918. Further citations from the diary will be footnoted only where the entry date would otherwise be unclear.

6 Barksdale, diary entry for October 3, 1917, note apparently added later.

7 Barksdale, diary entries for October 27 and 28, and November 1, 1918; see also Deetjen, diary entries for October 23 and November 1, 1917. Barksdale indicates he and Deetjen had dinner with the Morrisons on November 1; Deetjen notes he and Barksdale were to dine at Anderson’s that evening. Such a busy social calendar was bound to lead to confusion. On Mrs. Anderson, see Springs, Letters from a War Bird, p. 328 (note 20).

8 Barksdale, diary entry for November 3, 1917.

9 Hooper, Somewhere in France, letter of November 14, 1917; Foss, Diary, entry for November 15, 1917.

10 Barksdale, diary entry for November 18, 1917; here and elsewhere, the date supplied by Barksdale’s diary differs slightly from the one supplied by his R.A.F. service record; see The National Archives (United Kingdom), Royal Air Force officers’ service records 1918-1919, record for Eugene H. Barksdale.

11 See Barksdale, diary entry for December 8, 1917, and the relevant casualty cards: “Roberts, A.M.” and “Greed [sic], G.S.” (On the latter’s name, see Ancestry.com, British Army WWI Medal Rolls Index Cards, 1914-1920, record for G. S. Creed.)

12 Barksdale, diary entries for December 24, 27, and 29, 1917.

13 Barksdale, diary entry for January 26, 1918; this date may be in error. There is a casualty card for a crash involving “Miller, E. K. W.” in an S.E.5a at No. 74 T.S. on January 25, 1918, that probably matches this incident.

14 Barksdale, diary entry for April 26, 1918. I should note that Barksdale’s fellow second Oxford detachment member Raymond Watts recollected that Barksdale served for a time in the spring of 1918 as a ferry pilot; I find nothing to corroborate this in Barksdale’s diary or other records (Rogers, “Another of the War Birds,” p. 270).

15 A slightly racy account of Barksdale’s crash is attributed to Fry in the May 10, 1918, diary entry in War Birds, and Fry’s death is mentioned in the entry for May 11, 1918. Springs used Barksdale’s diary in writing War Birds (see Springs’s letter to Preston Boyden, cited on p. 110 of Davis, War Bird); this attribution of anecdote and revision of chronology sheds an interesting, albeit not particularly clear light on Springs’s use of sources.

16 Up until about this time, the school at Marske was the No. 4 Auxiliary School of Aerial Gunnery; its remit, number and name changed in May 1918 to Barksdale’s “No. 2 School of Aerial F[ighting] and G[unnery].” By the end of the month this was shortened to No. 2 Fighting School; see Jefford, Observers and Navigators, p. 51.

17 The men were presumably South African Wilhelm Jacobus K Knoll, killed when his Camel C1662 spun into the ground at Marske, and New Zealander John Alexander MacDonald Allan, whose Camel B5693 did the same at nearby Redcar. See “Knoll, W.J.K. (Wilhems [sic] Jacobus K.)” and “Allen [sic], J.A.M. (John Alexander Macdonald).”

18 Pershing’s cablegram 874-S recommending Barksdale (“non flying”) is dated April 8, 1918; cablegram 1303-R from McCain to Pershing confirming the appointment is dated May 13, 1918.

19 Barksdale, diary entry for June 7, 1918.

20 Barksdale, diary entry for June 16, 1918, and “Turner, F.C. (Frederick Charles).”

21 Barksdale, diary entry for July 15, 1918.

22 Barksdale, diary entry for July 31, 1918.

23 Townsend, “Aeroplane Squadron Locations during World War 1,” and Philpott, The Birth of the Royal Air Force, p. 404, give the location simply as Conteville. The location on Townsend’s map indicates it must be Conteville-en-Ternois.

24 Barksdale, diary entries for August 2 and 7, 1918.

25 Barksdale, diary entry for August 11, 1918. Interpolated into this entry in the transcript is an entry for August 10, 1918, which renders the dating slightly unclear. However, it seems fairly certain that Barksdale’s first O.P. occurred on the day (August 11, 1918) of Fraser’s fatal accident, which Barksdale mentions. See “Fraser, A.H.”

26 See the entry in for this date in Henshaw, The Sky Their Battlefield II; Henshaw locates the forced landing near “St. Vaast.”

27 Townsend, “Aeroplane Squadron Locations during World War 1”; see also Philpott, The Birth of the Royal Air Force, p. 404.

28 Barksdale, diary entry for August 14, 1918.

29 Cablegram 2456-S from Pershing to Adjutant General of the Army dated April 24, 1919, p. 3.

30 Barksdale, diary entries for August 22 and 25, 1918.

31 Barksdale, diary entry for August 30, 1918.

32 The combat record for this encounter is p. 115 of Individual Combat Records of Pilots with R.A.F. See also Cubbison, “‘His Hand on the Stick, His Wings on His Chest’,” p. 351, for another version of this combat record, and p. 350 on Barksdale’s victory credits generally. Cubbison mentions a newspaper article according to which the R.A.F. credited Barksdale with several victories (individual and shared), but the official American count, as recorded, for example, by Munsell, Air Service History, p. 225 (33), was one.

33 See “Barksdale, E. H.,” “Barksdale, E.H. (Eugene H.),” and “Turner, C.E.” Turner’s R.A.F. service record provides his full name and date of birth (October 6, 1897), but only the hospital admission date, not the date of the injury. See The National Archives (United Kingdom), Royal Air Force officers’ service records 1918-1919, record for Charles Edgar Turner.

34 Cubbison, “‘His Hand on the Stick, His Wings on His Chest’,” p. 351.

35 Barkdale, diary transcript, p. 29.

36 I have not found an R.A.F. incident card for this crash, nor for the crash on September 24, 1918. It is possible that they were a single incident, although Barksdale’s description of what he did with the plane (set guard over it vs. burn it) suggests two different crashes. Springs presumably had access to Barksdale’s original diary (see above), but, given his penchant for turning a good story into a better one, the War Birds account may be embellished or may conflate the best (the Scots rescuers and the burned plane) from two different incidents.

37 These are the final entries in the typescript of the diary; I have not been able to consult the original to see whether it continues.

38 Rogers, “Another of the War Birds,” p. 278.

39 Ibid.

40 Rogers, “Another of the War Birds,” pp. 278–79. Sloan, Wings of Honor, pp. 377 and 379, gives an account of the 25th, but does not include Barksdale in the rosters on pp. 388 and 428–29. “History of 25th Aero Squadron, (Pursuit),” pp. 5–6 lists the men assigned to the 25th, including Barksdale.

41 Doyle, “War Birds Pictorial,” p. 53.

42 See Cubbison, “‘His Hand on the Stick, His Wings on His Chest’,” pp. 352-53 for an account of his post-war career and his death.