(Towson, Maryland, September 5, 1895 — Longmeadow, Massachusetts, December 21, 1963).1

Oxford, Grantham ✯ No. 31 T.S. Wyton ✯ No. 56 T.S. London Colney ✯ Turnberry & Ayr ✯ Ferry pilot, pilots pool ✯ No. 60 Squadron R.A.F. ✯ July 2, 1918, and afterwards

Read, of all the men of the second Oxford detachment, probably has the most thoroughly documented ancestry.2 His forebears lived for many generations in South Carolina, some of them having been immigrant Huguenots fleeing the revocation (1685) of the Edict of Nantes, some having arrived in Carolina even earlier after brief sojourns in Barbados. A number of Read’s ancestors distinguished themselves during the Revolutionary War, including Arthur Middleton, a signer of the Declaration of Independence. Unsurprisingly, both of Read’s grandfathers, Benjamin Huger Read, Sr., and John Julius Pringle Smith, supported the Confederacy. Read’s father, Benjamin Huger Read, Jr., moved from Charleston to Baltimore in 1882; two years later he married Anne Cleland Smith of Charleston. They, like so many prominent Charlestonians were related, both descended from Henry Middleton (father of Arthur). In Baltimore Benjamin H. Read worked initially as a cotton broker and then went into partnership with James Savage Lynah, also originally from Charleston, to form Lynah & Read, a coal company.3

Francis Kinloch Read was the Reads’ youngest child and only surviving son.4 He was born in Towson (due north of Baltimore City); the family apparently moved to Sudbrook Park, a few miles west, sometime early in the new century. Read attended the Jefferson School for Boys in Baltimore before entering Johns Hopkins with the class of 1916; he appears not to have been enrolled at Hopkins after 1914.5 According to a story handed down in his family, he did not graduate because he “buzzed the Hopkins football field in a plane during the game.”6 In the absence of evidence of flying training prior to 1918, the jury is still out on the accuracy of the story.

In the summer of 1915 Read was at the Plattsburg Training Camp in New York; in the camp roster he is listed as working for the Amsterdam Casualty Company in Baltimore.7 He joined the Maryland National Guard (Battery A, Light Field Artillery) in 1916 and was stationed that summer at Tobyhanna, Pennsylvania.8

Along with fellow Baltimorean Parr Hooper, Read (“a tall good looking chap”) enlisted on June 24, 1917.9 Both men applied and were accepted for the Aviation Section of the Signal Corps. While Hooper was sent to Ohio State University for ground school, Read went to the School of Military Aeronautics at Hooper’s alma mater, Cornell.

Once at Cornell, Read, eager like most of his fellow students to get to France, became acquainted with the haphazardness of the U.S. military machine: “Another crowd leaves here to-day, about half of them to go to France and the rest to schools in the U.S. There seems to be no system of dividing them up, more or less of an alphabetical arrangement, and pull seems to play its part also. I wish that I could work some through Dr. Ames to get over there, . . . if it is just a matter of luck and pull I don’t see why I should not go, as well as somebody else.”10

Read was underwhelmed by much of the instruction at Cornell, but had the good fortune to be there when Lionel Wilmot Brabazon Rees of the Royal Flying Corps—who was in the U.S. to assist in setting up aviation instruction—gave some lectures in the latter part of July 1917: “He was very interesting and gave us a lot of dope. Very English, and was rather hard to understand.”11 It was good practice: Read would encounter Rees again in the spring of 1918, when the Victoria Cross recipient was in command of the School of Aerial Fighting at Ayr in Scotland.

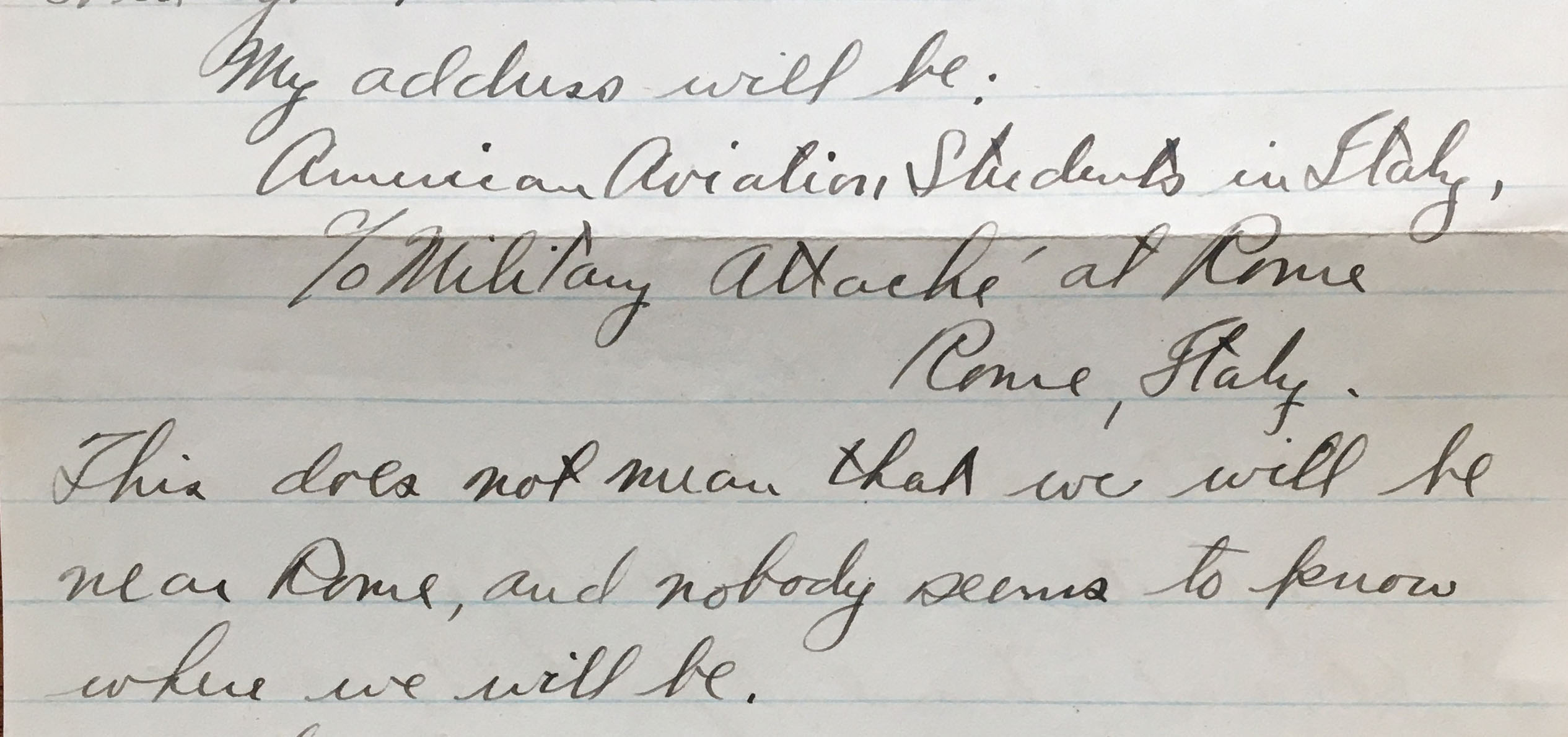

Sometime in August 1917, the possibility of aviation training in Italy was raised, and men were asked to volunteer to go there rather than to France. Read evidently signed up, and when his Cornell ground school class graduated on August 25, 1917, he and fellow-Baltimorean Galloway Grinnell Cheston, along with ten others from their class of sixteen, were selected to go to Italy.

The men proceeded to Mineola on Long Island and, a little over three weeks after completing ground school, set sail from New York on the Carmania as part of a 150-man strong detachment bound for Europe. After a brief stop at Halifax, the Carmania joined a convoy and began the Atlantic crossing on September 21, 1917. The men of the detachment, travelling first class, had plenty of leisure, apart from daily Italian lessons conducted by Fiorello La Guardia, who was travelling with them, and submarine watch duty towards the end of the voyage.

When the Carmania docked at Liverpool on October 2, 1917, another lesson about military (dis)organization awaited the men. They learned that they would not go to Italy but remain in England and repeat ground school at the Royal Flying Corps’s No. 2 School of Military Aeronautics at Oxford University.12 The quondam “Italian detachment” became the “second Oxford detachment” (the first, consisting of fifty American cadets, had arrived at Oxford a month previously). “Of all the bitter disappointments this is the worst, but I suppose that it will turn out all right in the end. We were shipped down here [Oxford] without any notice at all, and will continue our studies for anywhere from three to six weeks, and then to some British squadron, probably.”13

Oxford, Grantham

The cadets spent their first night at Oxford in various colleges, but the next day were divided into two groups. Sixty men were housed in The Queen’s College and ninety in Christ Church College. Read shared a room at Christ Church with men he knew from ground school at Cornell: Robert Alexander Anderson, Guy Maynard Baldwin, and Lloyd Ludwig.14 Once classes started, Read was favorably impressed with the instruction. He also appreciated the time set aside each day for exercise: “Four of us took a short [bicycle] ride into the country a few days ago in the time allotted for sports, which is from after lunch, at one o’clock, to four fifteen. We usually row, but took an afternoon off.”15

Not long after arriving at Oxford, Read realized that William Osler—who had helped found the medical school at Hopkins and taught there from 1889 until 1905—was living in Oxford. Read’s uncle by marriage, William Sydney Thayer, had worked closely with Osler in Baltimore, and the families evidently knew one another. Read at first opportunity went to visit the Regius Professor of Medicine and, like so many young people, was warmly welcomed at 13 Norham Gardens, despite the Oslers being “very broken up by Revere’s death”16—their son had died at the end of August 1917 of wounds sustained near Ypres.

About three weeks into their time at Oxford, all the American cadets were relocated to Exeter College, but before the move, a panoramic photo of the cadets, both American and British, at Christ Church was taken. Read mailed a copy home, noting in a letter written October 29, 1917, that “I am on the right fairly low down.”17 In that same letter he wrote that “We expected to be assigned and go out to squadrons to-day, but no news as yet. I suppose because we are so anxious to go. Two ground schools are a little too much for anybody.”

Ground school was, indeed, nearly over, but there was more disappointment in store. Read next wrote from Harrowby Camp near Grantham in Lincolnshire, to which all but twenty of the men of the detachment had been sent on November 3, 1917. “We have moved again and are now at machine gun school, where we will probably be here [sic] for three or four weeks, about the first of December, I suppose.” On the plus side, “I surely was glad to get away from Oxford, for although the place was very pretty, the old colleges were cold as the deuce and accomodations [sic] exceedingly poor. Here we are fixed very well. We rank as officers, have our own mess and quarters, and associate with the British officers, also have ‘batmen’ to look after us and shine our shoes, make our beds, etc. which makes it very nice, and Army life takes on an entirely new aspect.” Read had learned not to count chickens: “We expect to go to squadrons from here, but as we were supposed to go from Oxford, it is rather doubtful.”18

As at Oxford, monotony was relieved by opportunities to explore the area. It appears that on one Saturday Read was able to go “out with the beagles,” and then to tea at Boothby Hall, and that, out again the next day, he visited Christopher Hatton Turnor at Stoke Rochford Hall. Both of these grand residences were situated just south of Grantham.19

In mid-November, places opened up at squadrons for fifty men, but Read was among those who remained at Grantham for the second of the two-week machine gun courses (the first had been on the Vickers, the second on the Lewis gun). Finally, after “a big celebration on Thanksgiving, a football game, and a huge dinner, also half a day or more off,”20 the remaining men were sent to squadrons.

![Bottom portion of a page; handwritten in ink is the heading "49 Wing R.F.C. No. 31 Tr. Squadron Wyton." under the heading are the names: A. J. [sic] Bird, J. H. Fulford, T. F. Hardin, F. K. Read, W. W. Wait, A. A. Gaipa, G. C. Cheston, A. H. Chapin.](https://parr-hooper.cmsmcq.com/2OD/wp-content/uploads/Bird-et-al-assigned-to-Wyton-Dec-3-from-Foss.jpg)

No. 31 T.S. Wyton

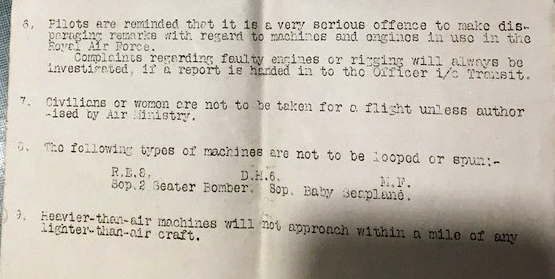

Read had the good fortune to begin flight training immediately. His log book records two flights as a passenger in a DH.6 (a plane designed for training) on December 4, 1917.21 He was able to go up again on the 8th, 10th, and 11th, and again on the 17th; there was much attention to landings. On December 18, 1917, Read’s (B) flight O.C., Lt. Evans (probably Dudley Lloyd-Evans) took him up in DH.6 [A]9723, and over the course of forty-five minutes, they made thirteen landings.22 Another instructor, Lt. Jones, took him up briefly for a test, and then sent him off for an initial ten minute solo flight, followed quickly by a seventy-five minutes solo flight, during which the engine of DH.6 A9723—which up until then had been fine—“seized up,” and Read, on this, his first real solo flight, made a forced landing. He wrote home the next day (in a letter that was, to his chagrin, published in the Baltimore Sun):

I started flying about two weeks ago and did my first solo yesterday; a little short of four hours (in two weeks) dual. It is fine and I am awfully glad I came in for it. I went up to about 3,000 feet and went nearly over to —, which is about 15 miles away, following a railroad. . . . After I had been up for about an hour, one of the connecting rods broke and the old motor stopped dead. I think I gained several gray hairs in the next five seconds, but I was up about 1,500 feet, so had a pretty good gliding distance, picked out a field that looked pretty soft and headed for it and landed without mishap. It really was very simple but rather disconcerting at first.23

Nothing daunted, Read the next day made two long flights punctuated by many practice landings. His letter of December 19, 1917, continues: “I finished my four hours’ solo today and now go to an advanced squadron.”

The advanced squadron was No. 56 Training Squadron at London Colney. Before going there, however, Read had Christmas leave, at least part of which he spent with “some wonderful people named Buckley. They have a large estate near London, where Mr. Buckley runs a ‘clean’ milk’ farm. Very scientific and all the appliances they have in good dairies at home.”24 Wilfred Buckley had lived for a time in New York, where he married an American, Bertha Leslie Terrell. On returning to England, he designed and had built Moundsmere Manor, where Read visited the couple.25 It appears that the Reads had known of or been acquainted with the Buckleys (or the Terrells) in the U.S.26

Read reported to No. 56 T.S. on December 27, 1917. A number of second Oxford detachment men, including Anderson, Baldwin, Thomas John Herbert, Hooper, and probably Wait, were already at No. 56 T.S.; others were at No. 74 T.S, which was also at London Colney.

It was just over a week before Read made his first flight at 56 T.S. On January 4, 1918, instructor John William Rayner took him up as a passenger in an Avro 504J; this was a plane specifically designed for training. Read went up again on the 6th with instructor Bernard McEntegart and the next day with “Lt. Pigot.”27 Read was enthusiastic about the planes and flying at 56; on the 7th he wrote his father:

The machines here are fine, you really feel as if you were in the air. At Wyten [sic], they were so big and heavy that you felt as if you were being dragged through the air, but these see[m] to float along. They have rotary engines, which gives you more to do, for on the stationary ones all you have to do is open the throttle and let them go, but these have to be handled more gently, and you have to use a spark. I go from these on to scout machines which are here too, but you can do any stunts on these machines, and that is about all you get here. The scouts are a good deal faster, and that is about all. The instructors here are stunt pilots, so we get lots of it! You seldom fly under four or five thousand feet here, while at Wyten the instruction was at about five hundred. It is great sport. I wish you could go up.

Read’s log book shows him flying again on January 12, 1918, but after that not until January 25, 1918. On January 14, 1918, He wrote his oldest sister, Elizabeth Middleton Read, that “The flying is going much slower here than at the last squadron. There are twelve of us here and some Englishmen and very few machines, and someone is always breaking them up, so we sit around and freeze most of the time.”

Read took advantage of some of his non-flying time to get in touch with relatives living in England; he had written his mother in November that “The Wilkies wrote me a very nice letter asking me to come and stay for a week or more. I’m going to try to go up some week end if I can get leave. . . . Sissie also mentioned the Jeudwines in London, so I think that they are an excellent excuse to get off another weekend.”28 Mrs. Wilkie was the former Allene Huger, related to Read’s father through both the Hugers and the Middletons; she had married Scots born Robert Henshaw Wilkie, and the couple and their daughter Harriet (Hattie) Huger Wilkie now resided in Liverpool. Read was able to stay with them towards the end of January, and also took Hattie to a show when she was visiting in London the same month.29 The Wilkies became a family away from home for Read and provided a convenient poste restante as he continued to move from place to place. Mrs. Jeudwine was the former Harriette Louise Lesesne of Charleston. Her first marriage had been to Robert Pringle Smith, Read’s maternal uncle; after the latter died she married English barrister and historian John Wynne Jeudwine, who had come to the Carolinas for his health in the 1880s; the couple settled back in England sometime early in the new century, eventually residing in London, where Read was able to visit his “Aunt Leila.”30 Read was also pleased to encounter fellow Baltimoreans, Anna Melissa Graves—who had arrived at Liverpool at almost the same time as he had and was in England to do social work31—and Robert Wilkinson Johnson and his wife, the former Rose Stanley Gordon Haxall; Johnson had studied medicine at Hopkins and since June 1917 had been serving with the U.S. Army Medical Corps in England.

Despite limitations on flying time, Read was making good progress. After two flights on January 25, 1918, first with Alexander Augustus Norman Dudley Pentland and then with William Jameson Cairnes, and another very brief flight with Pentland on January 27, 1918, Read was able to make two solo flights in Avro [C]4481 on the 27th and another one of nearly an hour the 28th.

It was perhaps on the 28th that an incident occurred that Eugene Hoy Barksdale, stationed at No. 74 T.S., recorded in his diary the next day: “While Jack Fulford & Reed [sic; sc. Read] were changing places in an Avro the engine was accidently switched full on & started off at full speed with Jack F. hanging on by one hand. As it was about to take itself off he dropped & we thot broke leg but not so. Is doing nicely. Machine crashed.”32

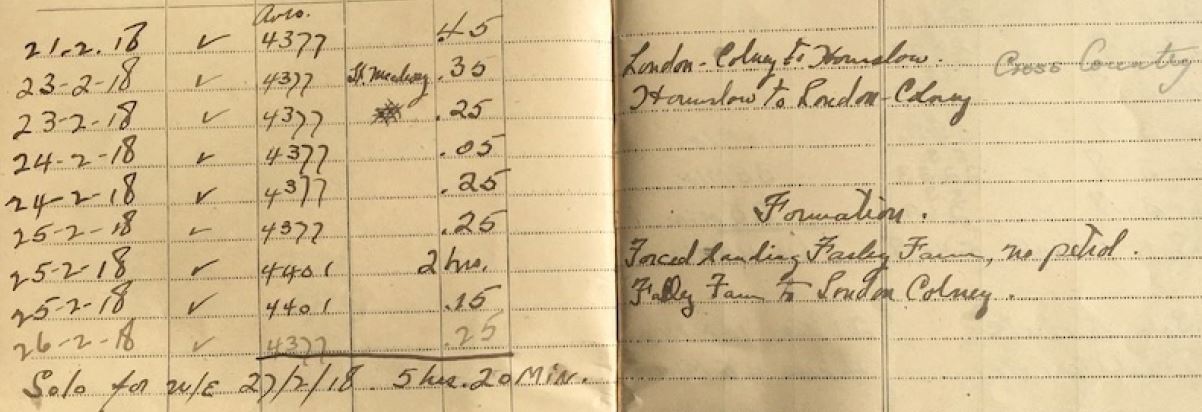

In February 1918, Read was able to put in a good many more hours in the air than in January, many of them solo. On February 23, 1918, he made a cross country flight to Hounslow and back, thus fulfilling one of the requirements for graduation from this stage of R.F.C. training. Two days later he experienced his second forced landing, again with no ill consequences:

Three of us set out a few days ago to see England in two hours, and we saw a good deal and had a great time, only we stayed up little too long for two of us gave out of gasoline. (Same old trick.) I landed in a field, a beautiful field it was, and telephoned to the aerodrome for more gas, being about ten miles away, and got back before dark, the other fellow gave out too far away to get home that night, and the third one, who had a larger tank than we, got lost and finally hove up at an aerodrome by London, found out where he was and then came back. The Major was ripping, but we had some good sport, and he greeted me with a very cheerful smile the next day, so I guess he got over it.33

The other two pilots are not identified; the Major was presumably the O.C. of 56 T.S., Gordon Roy Elliott. It appears that Read landed at Folly Farm on the south edge of Monken Hadley Common and about ten miles south-southeast of London Colney. 34

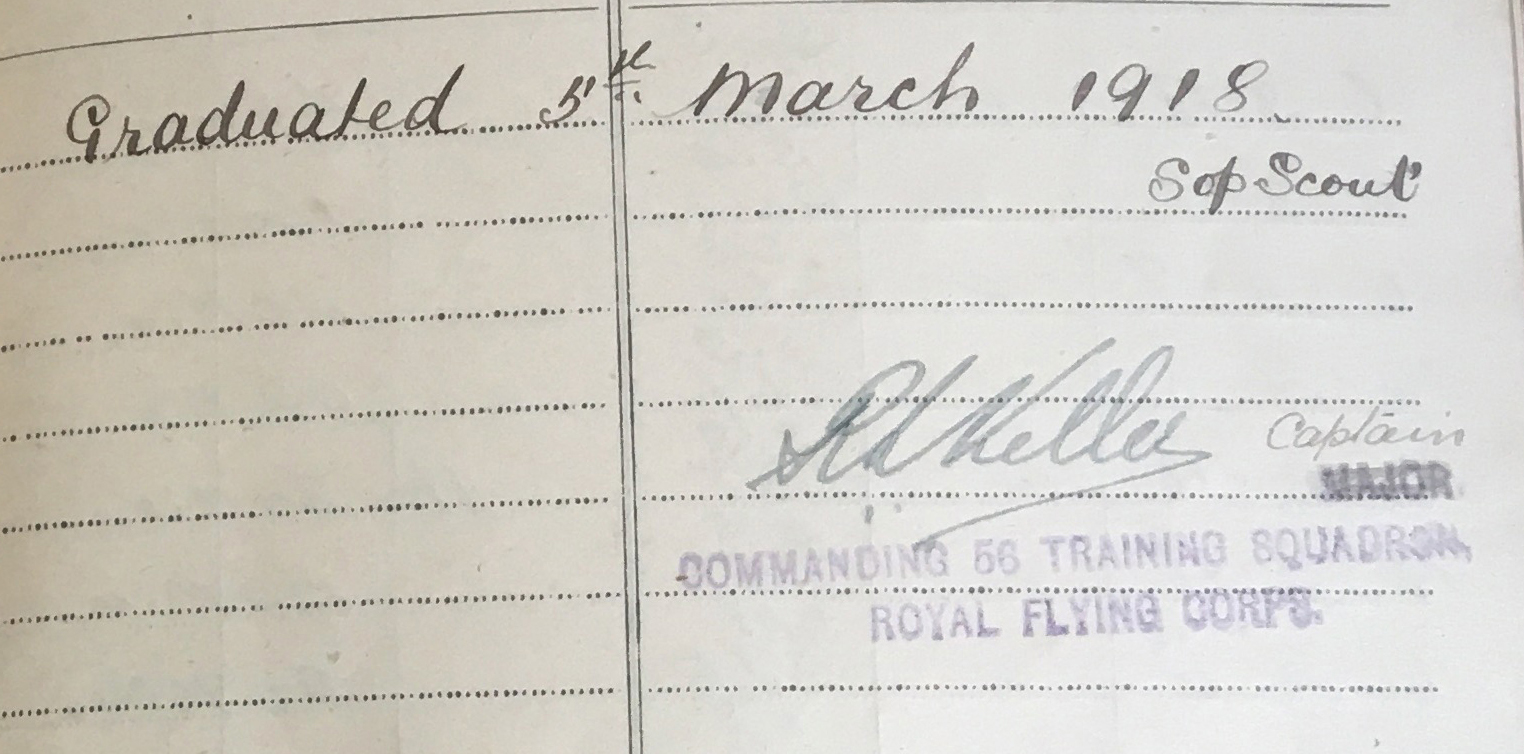

On February 28, 1918, Read flew a single seater and service machine for the first time, a Sopwith Scout (Pup), and the same he day passed his height test in the same plane ([B]2233), i.e., he flew at 8,000 feet for fifteen minutes or more, thus fulfilling two more graduation requirements. By the end of the day on March 4, 1918, he had accumulated just over twenty-five hours flying (dual and solo), the last graduation requirement.35 The next two-page spread in Read’s log book bears the single entry: “Graduated 5th March 1918 Sop Scout” and is signed by Captain R[oderick] L[eopold] Keller.

Read had also qualified for his commission as a first lieutenant. The information was forwarded to Pershing, whose March 7, 1918, cable to Washington included Read’s name among those recommended for commissions; the confirmation came back ten days later.36

R.F.C. graduation was rewarded with four days leave. Read took the opportunity to go to Plymouth and Torquay, where he was grateful for sunny skies on the southwest coast after the weeks of poor weather in the vicinity of London.

Back at No. 56 T.S., on March 14, 1918, Read flew a Spad 7 ([A]9136), another single-seater, for the first time. Herbert and Hooper had also progressed to flying Spads, and the next day, as Hooper recounts it, the three of them flew Spads to Wyton: “Tommy Herbert led Frank Read and myself about 40 miles to his elementary training squadron. . . . It was great sport because we all are very chummy and went on sort of a lark. Frank and l had almost no idea where we were. We could watch each other all the time. We followed old Herb like a dog’s tail and trusted he knew where he was going.” Hooper continues:

Then Frank and I planned to fly to Oxford. We studied the map one night. The next morning [March 16, 1918] was dud but we decided to go about 11 o’clock. I led and stayed down low 1000 feet so as to be sure to see all branches of the railroad I was to follow. It was some fun. If I got into mist so that I could not see the ground I would slide slip down and Frank stuck right along. We went by towns so fast we hardly got two looks at them. Then we got to where we should see the Thames, sure enough there it came along and there was Oxford. . . . We went up river, found the aerodrome and landed. As soon as we had been filled up again we started home. We went 10 miles down the Thames to Abington, back again to within two miles of Oxford and then the sixty miles home via Northolt in 45 minutes. Some traveling I should say. We planned some other trips but got posted to Turnberry before we could carry them out.37

On March 20, 1918, Hooper wrote from Turnberry that “They shipped us out of London Colney Monday [March 17, 1918] afternoon. Tommy Herbert, Frank Read, and myself were all posted here together. We were allowed Monday afternoon and evening in London, and took the train at 8.50 Tuesday morning for here. We arrived at 9.30 p.m.”

During their week and a half at the School of Aerial Gunnery at Turnberry (on the west coast of Scotland, about forty miles southwest of Glasgow), the men stayed in what in peacetime was the Turnberry golf course hotel. Their “window looks right out over the Firth of Clyde and Irish Sea,” and the accommodations in general were unexpectedly luxurious.38 Read, Hooper, and Herbert roomed together, which, according to Hooper, led to his writing home less frequently than he would have liked: “my roommates Tommy Herbert and Frank Read are getting so blooming congenial that when we get together here in the room to write we spend most of our time laughing and talking.”39 This may explain why there appear to be no letters from Read from Turnberry.

At the end of March, the three men went up the coast to Ayr, to the School of Aerial Fighting. They roomed now at Carleton House, a few hundred feet from the shore and the Firth of Clyde, and “though we don’t live in a hotel, we have a pretty good house, and there are about twenty in it. Fourteen Americans and the rest English.”40 Too few planes and too many student pilots meant that there was no flying initially, but instead opportunities to explore Ayr and the surrounding countryside. On one day Read and Hooper made an extensive and much enjoyed bike tour from Ayr, via Kirkmichael and Straiton, to Loch Doon, and back, documenting some of their stops with photos.41 The next day Read wrote: “We covered about fifty miles and are more or less of wrecks to-day.”42

On April 7, 1918, Read wrote to his mother that “After not flying for about two weeks I started again day before yesterday, and it felt fine to be in a machine once more. The instruction here is wonderful, I have never seen such flying as is done by the instructors. I hope I can catch on to some of it.” He practiced stunting initially in an Avro, and then on April 11, 1918, made three flights in Spads. The first was in A9140, and it may have been this flight that was photographed by Read’s fellow second Oxford detachment member John L. C. Rorison.42a The third flight that day, in [A]9139, lasted forty minutes and did not end well: “Engine dud over Kirkconnel” (about twenty-five miles inland from Ayr), “Laid it on its back on a hillside of Bonnie Scotland.”43 Read was evidently unhurt, but the plane was apparently a write off.44

Intrepid as always, Read flew again the next day, going up in an Avro with instructor Robert Wallace Farquhar for some “dual stunting.” Three days later he took “Baldwin”—presumably Guy Maynard—up as a passenger in an Avro for a flight lasting nearly two hours, returning to take off yet again, this time back in a Spad. On April 17, 1918, he and Hooper both made brief flights in the German Albatros DI (391/16) that had been captured in 1916 and was used for training at Ayr.45 They made these flights just in time. Rorison, before he left Ayr a few days later, took photos that show the Albatros, wings crumpled, after a crash.45a

Also on April 17, 1918, Read and Hooper went for a joy ride in Avro D27. In a letter home Hooper gave a full description of this enjoyable flight with the unflappable Read. Their only regret was, as Hooper remarked, that “we did not have a girl to go see.”46 This state of affairs did not last. Not long afterwards Read wrote his mother that “My social activities are picking up. I have been to a whole dance and went to tea with a very beautiful young lady in a whole big castle. Hot stuff! . . . One Parr Hooper and I flew out to tea in an avro, if you know what that is, landed in a field, and a special constable came along so we switched him to guard the machine and had a wonderful time. The girls in Scotland have it all over the English ones, and some of them can dance like real human Americans.”47

The background to this visit is that Hooper had been invited to Sorn Castle, home of Thomas Walker McIntyre, for a dance and dinner the evening of his joy ride with Read (Read had apparently been invited to a different dance). Evidently smitten with the daughter of the house, Hooper was delighted to be invited back to tea with the McIntyre family at Sorn Castle on April 21, 1918, and took Read with him. Hooper got their flight commander’s permission, and, although “Two o’clock seemed very early to leave for tea, . . . there was a storm brewing, a little rain (almost sleet) was falling, so we decided we had better get off before we were made to stay home. Frank sat in front and I piloted from the rear.”48 The weather cleared; they landed briefly at Failford before going on to Sorn Castle. “We had a fine tea. Afterwards Mrs. [McIntyre] played the organ. Then we got out the victrola and had a dance. It surely was a wonderful place and wonderful people. Frank and I had the time of our lives.”49

On April 23, 1918, Read was able to fly an S.E.5a ([C]5323), a fast single-seater fighter plane, the type he would fly in France, for the first time. Hooper completed his training slightly ahead of Read and by April 26, 1918, was ready for a week’s leave; he regretted that “Frank Read has not finished his time yet so I will have to go alone”50 —which Hooper did after he and Read had taken part in an officers vs. mechanics baseball game at Ayr on April 27, 1918. Read finished up at Ayr on May 1, 1918, by which time he had gotten in over six hours flying time on S.E.5a’s.

On May 2, 1918, Read wrote his mother that he “was going to report to London tonight for overseas, but have to stay here a day or so for this court-martial. We are going to have about four men to try and expect to have a big time.” Both Read and first Oxford detachment member Paul Stuart Winslow kept a photo of themselves and the other officers of the court martial, but no record of who was being tried or for what offense. Read continues: “Five of us here are trying to arrange to go to the same squadron in France and I think that we will be able to work it. I hope so anyway.” He, Herbert, Watts, and Winslow were presumably four of the five men; George Augustus Vaughn or Hooper may have been the fifth. “By the time you get this I will have started somewhere, so will wire you when I go to France. I may be a ferry-pilot for a week or two, across the channel or in England.”

The court martial appears to have detained Read in Ayr for nearly a week, for he did not leave Ayr until May 8, 1918, when he, and probably Herbert and Winslow, caught a night train down to London.51 On May 10, 1918, Hooper, in London awaiting orders, encountered Read, Herbert, and Winslow, “starting to ferry pilot,” and they, along with Roland Hammond Ritter and Duerson Knight went to the American Officers’ Club and “had a fine meal there, fried chicken on a meatless day, and lots of fun.”52

The day before his first ferrying job, Read wrote his mother and noted that “Two of my very good friends here have been killed training, and several others who came over in our detachment.”53 He was not unusual in seldom mentioning air fatalities to his family, but on this occasion, he had probably just heard about Wait—who had been with Read at Cornell and trained with him at Wyton and London Colney—and dropped his guard. Wait, still at No. 56 T.S., had died on May 9, 1918; Ludwig, who had also been with Read at Cornell and roomed with him at Oxford, had been killed at Castle Bromwich in February.

Read was attached to the Central Despatch Pool in London for ferrying duty for about three and a half weeks. He flew newly manufactured planes from Aircraft Acceptance Parks in Coventry, Bristol, Hendon, and Brooklands to the coast (Tangmere, New Romney, Dover, and Lympne), or in one instance, to the Central Flying School at Upavon in Wiltshire. In all he made twelve flights, including four from Lympne on England’s southeast coast to the airplane reception park at Marquise, France, returning by boat: “It only took about twenty minutes to cross the channel going over, and about two hours coming back. I prefer the former.”54 In addition to ferrying S.E.5a’s, Read flew an A.W. FK.8 ([D]5002), a Bristol Fighter (D8009), DH.9s ([D]5661 & [C]2185), and a Sopwith 5F1 Dolphin ([D]3717)—none of which he had flown previously. By the time he finished ferrying, Read had added almost seventeen hours to his solo flying time, nearly eleven of them in S.E.5a’s. As he remarked in a letter to his mother, “I have flown ten types of machines so far and much prefer the one I go to France on, which is very lucky for me.”55

Read made his last flight as a ferry pilot on June 5, 1918. Three days later, June 8, 1918, he wrote from Folkstone: “Here I am on my way to France at last. . . . We had to catch an eight o’clock train and got down here to find that the boat is not leaving until two o’clock, so we won’t get over until about four-thirty. There are about seven of us going over together and four of us are going to try and get in the same squadron. We go to British squadrons. Herbert, Winslow, Watts, and myself.”

The four men went initially to the pilots pool at Rang du Fliers. There is a photo taken some time between June 8 and June 14, 1918, of men at Rang du Fliers that includes Read, Herbert, Winslow, and perhaps Watts, in John Chadbourn Rorison’s photo album; the men are constructing trench works.56 Read remarked that “[I] have been getting plenty of exercise in the form of manual labor, which I was much in need of.”57

Herbert, Watts, and Winslow were stuck at Rang du Fliers for some time longer, but Read was posted on June 14, 1918, to No. 60 Squadron R.A.F. 58

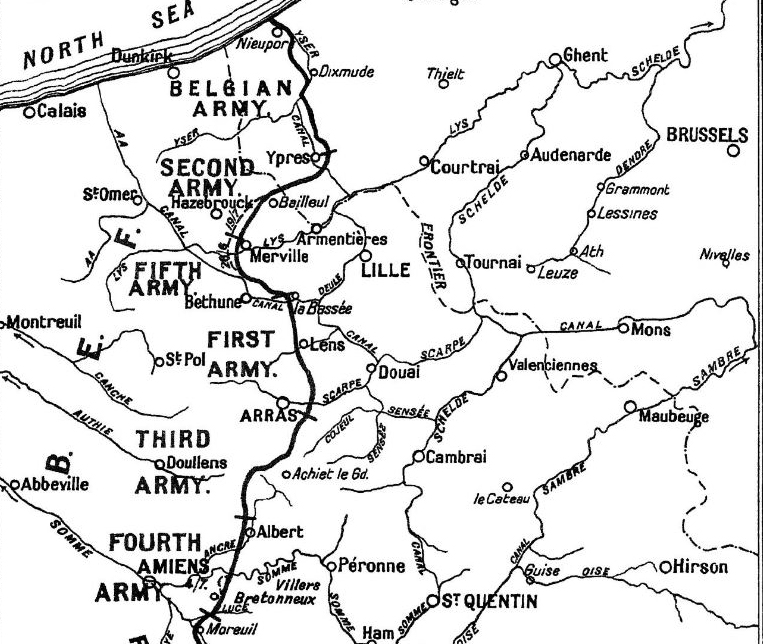

No. 60 Squadron was originally (1916) attached to the 13th Wing of III Brigade R.A.F., supporting the Third Army. It was reassigned to the Second Army during the Battle of Passchendaele in the latter half of 1917, by which time it was flying S.E.5a’s. At the opening of the German Spring Offensive in March 1918 the squadron moved back south, returning to the 13th Wing, III Brigade, Third Army. The Third Army front ran approximately from Arras south to Albert. The squadron initially flew out of an aerodrome at La Bellevue; it soon moved to Fienvillers, and then in early April 1918 to its longer-term aerodrome at Boffles, some twenty-five miles due west of Arras. 59

Read was the only man from the second Oxford detachment assigned to No. 60 Squadron. Very briefly, on June 29, 1918, it looked as though Herbert and Winslow would join him. Winslow wrote in his diary that day that “At last, after three weeks here [Rang du Fliers] Tommy [Herbert] and I were posted to 60 Squadron. At 11 o’clock 60’s tender came and picked us up. Bag and baggage. We stopped at Abbeville and then carried on to 60, arriving at 2:30, and were told that we did not belong there but at 56, and we were shipped off without any lunch. Poor Frank Read nearly cried when we left. . . .”60

Read’s letters home indicate he was otherwise pleased with his assignment: “I am at a squadron at last, but will probably not start flying over the lines for a week or ten days. This is a great place, no red tape or anything annoying. Just so long as you are on the job at the right time you can do what you want, which makes it pretty good. Living in tents and the food is fairly good, so it is very comfortable. No other Americans came with me, but there are one or two here in the British service.”61 (The other Americans at 60 at this time were John Sharpe Griffith of Seattle, Washington, and James Grantley Hall from Massachusetts.62)

The Third Army front was comparatively quiet during this period; the German Spring Offensive had stalled, and the Allies would not launch their Hundred Days Offensive until early August. No. 60 Squadron was mainly tasked with flying offensive patrols—flights into enemy territory to look for and destroy enemy planes and balloons; from time to time the S.E.5a’s also escorted planes from other squadrons on bombing missions. The squadron made from one to four patrols almost every day during the period that Read was there. They flew in small formations of one flight, with from as few as two, up to as many as eight planes. Based on references to enemy aircraft sightings noted in the squadron record book, their patrols took the planes of 60 Squadron north of Arras almost to Lens, south of Albert and the Somme to the vicinity of Villers-Bretonneux, and east as far as Peronne, forty miles from Boffles and potentially nearly twenty miles inside German-held territory, depending on their flight path. 63

Four days after arriving at 60, Read made his first practice flight in S.E.5a D6183. Two days later (June 20, 1918) he was pleased to report that:

I had my first trip to the lines this morning. An acting flight commander took me up to show me the general lay of the land, and the good land-marks. It was a good trip but the clouds were low and we could not get above 2,000 feet. I saw several batteries in action, and the Huns got after us with anti-aircraft guns; the man I was with started twisting his machine around, and you can bet your boots I was close behind him in mine. You could hear the old things go off–wooff, but none of them came very close to us, and no one ever seems to get hit. 64

The acting B flight commander was Alfred William Saunders. Yet another unfulfilled expectation (leaving aside “no one ever seems to get hit” for the moment): Read had been given to understand that “Capt. Maxwell . . . is coming to this squadron in a few days, and I expect he will be my flight commander, I hope so for he is very good, and I knew him at Ayr.”65 Gerald Joseph Constable Maxwell had been with No. 56 Squadron before being posted to Ayr as an instructor; in early June 1918 he was back at No. 56 for a “refresher course.”66 Meanwhile 56 flight commander Cyril Parry was due to return to England but chose to remain at the front, and it was he, rather than Maxwell (who stayed with 56), who in early July 1918 took over as 60 Squadron’s B flight commander.67

Poor weather meant little flying for two days, but from June 23 through June 26, 1918, Read got in more practice flights and visited the lines again; he began consistently flying S.E.5a B151. On the morning of June 27, 1918, Read took part in his first offensive patrol—which the squadron record book also describes, in Read’s case, as “visiting lines,” perhaps a way of fudging the fact that, according to R.A.F. regulations, new pilots were not supposed to cross the lines until they had been at a squadron at least two weeks and had accumulated 100 hours flying time. 68 In this five-man O.P. led by Saunders, the planes were in the air for two hours and evidently flew to the northeast, for the record book indicates that Saunders reported: “3 Albatross Scouts seen chasing RE8 near Lens @ 9.55.” Read reported: “chased E[nemy]A[ircraft] away & they retired East.” Because of the prevailing westerly winds and the fact that German planes usually remained on their side of the lines, this scenario—planes sighted but not engaged because they escaped east—was an oft-repeated one.

The next day (June 28, 1918) the planes of 60 Squadron flew three missions, and Read took part in both of the offensive patrols flown by the eight planes of B flight; one set out at 8:30 in the morning, while the other took advantage of the long summer evening hours, taking off at 7:30 p.m., returning at 9:25. On both missions a number of enemy aircraft were sighted in the vicinity of Arras, Bapaume, and Albert, but none engaged. No missions were flown the next day, but four were flown on June 30, 1918; Read took part in two of them. At noon and again at 5:00 p.m., Saunders led Read, Harold Buckley, Harry Andrew Gordon, and John Everard Churchill MacVicker over the lines. Read reported on the earlier patrol “2 two seaters seen over Combles @ 7000 Feet @ 12.45 ”; Combles was about thirty-five miles southeast of Boffles. Another plane was sighted nearby at 2000 feet, but “all retired east” (Saunders). Read returned early from the afternoon patrol, “cowling torn away.”

The engine cowling was evidently replaced overnight, for Read flew B151 again on two two-hour offensive patrols on the first day of July. In the morning the five planes that took off at 8:40 apparently flew southeast (Saunders reported “1 two seater seen at 18,000 feet near Doullens at 8:55—retired east before patrol could climb to him”) and continued on that course to the Somme. Read reported “11 Pfalz Scouts seen at 15,000 feet near Peronne at 9-15—seen again at 10-20 East of Bray going north, having been joined by 3 more. One Flight at 18,000 & 1 Flt at 15,000 — not attacked owing to EA being 4000′ above patrol.” No enemy aircraft were seen during the afternoon patrol.

The next morning, July 2, 1918, Saunders led a six-plane offensive patrol that included Read in B151; they set off at 9:15. According to Saunders’s combat report:

At 10.45 a.m. at about 11000 feet with my patrol of 5 machines . . . made our last trip into Hun land before returning home. Saw a formation of 6 silver Phalz [sic] scouts at about 4000 feet over Bayonvillers flying towards Villers Brettoneux. E.A. evidently did not see us so with patrol turned further into hun land and attacked third E.A. at tail end of left hand side of E.A. Formation . . . who went vertically downwards. Passed over him in my dive and saw the second E.A. on left of leader suddenly turn to the right and crash into the E.A. leader, both machines collapsing and crashing in a small finger shaped wood (Bois de Pierret).69

Saunders attempted to collect the members of his patrol while further engaging with other enemy planes. An annotation to Saunders’s report, apparently by squadron C.O. Barry Fitzgerald Moore, states that “early in the fight Lt. Read was wounded and was escorted back by Lt. Gordon”—the second half of the statement has been crossed out. According to the squadron record book, Read made a forced landing at 10:50 at the aerodrome of No. 3 Australian Flying Corps, “machine OK.” He had thus managed to fly northwest into Allied territory; 3 A.F.C. was at Villers Bocage, about halfway between Villers Brettoneux and Boffles. Read was taken to No. 20 Casualty Clearing Station at nearby Vignacourt. Plane S.E.5a B151 was fetched and returned to Boffles by Hall the same day.

Perhaps the same day or the next, Saunders wrote to Read: “Dear old Read, All the boys wish you the very best. The Major and Colonel are very bucked with your effort, and I personally am proud of the way you came down to help us. You will be pleased to hear that we bagged three of the hun patrol. . . .”70

Two days after being wounded Read was well enough to write an exasperated letter to his mother:

Here I am in a blasted old hospital, if it isn’t rotten luck I don’t know. We came down from about 13,000 ft. on to some Huns at about 1,000. As we were behind the Hun lines, they opened up with machine guns from the ground and of course one of the blasted things had to hit me. It went through the left side of my chest, but didn’t do much damage, and if I didn’t have to lie on my back, would be fairly comfortable. I will not be able to fly again for several months, unfortunately, but am healthy enough, so don’t worry.71

Cables began flying back and forth. One sent by Read reached his father on July 8, 1918—well ahead of the letter to his mother—and reported that he was “slightly wounded.”72 This was worrisome, but much less alarming than the cable sent by the War Department on July 22, 1918, which reported Read “severely wounded.” However, the same day a cable from Read’s uncle Thayer (who had arrived in Europe in February 1918 to serve as Director of General Medicine for the American Expeditionary Force) reported that Read was improving, although likely to be incapacitated for about three months.73 A cable from the Buckleys reporting encouraging news from one of Read’s nurses was “an immense relief.”74

Read remained at No. 20 C.C.S. through July 18, 1918, when he was well enough to be transferred to a British military hospital, No. 8 General Hospital at Rouen. “I left the C.C.S. yesterday [July 18, 1918] at ten o’clock A.M. and arrived here this morning at six, covering in all about one hundred and fifty miles, traveled in a baggage car with three tiers of stretchers, I was on top I’m glad to say. It was not a half bad trip. I was sorry to leave the C.C.S. for everybody there was fine, and we were in a tent and it somehow did not seem like a hospital, and hospitals are most objectionable in my opinion.”75

About a week after arriving at Rouen, Read was very pleased to be visited by Thayer, who, in turn, was glad to be able to forward a first-hand report of his nephew’s recovery to Baltimore.76 On August 12, 1918, Read wrote home that “My friend Tommy Herbert arrived here yesterday, with a fractured leg, how bad I don’t know yet, perhaps we can fly up to get somewhere together, I hope so.” The next day: “Tommy Herbert had a very bad leg, a piece gone out of the bone, so they sent him right away to England.”

Read, however, remained at Rouen until mid-September, and then, finally, was transferred to a hospital near London, apparently U.S. Army. Base Hospital No. 29, located at St. Ann’s Hospital in Tottenham.77 In mid September he wrote from the American Officers’ Club at 9 Chesterfield Gardens, just north of the hospital: “Here I am again, but only for dinner. I am in a hospital at present just about on the edge of London, which is not very nice, but I expect to get out of it in a day or so, and come to a more central place, however I hope to get in the country somewhere, for I am not very fond of this town. The colonel in Rouen sent me for a Royal Air Force hospital, but of course I did not get to one. I should a great deal rather be doing something. However it can’t be helped. I am seeing Mrs. Buckley to-morrow.”

From Base Hospital No. 29 Read was glad to be transferred to the American Red Cross Convalescent Hospital No. 101, located at Ford Manor, the country home of Herbert Henry Spender-Clay and his wife, the former Pauline Astor, near Lingfield in Surrey. On October 7, 1918, he wrote: “This is a wonderful place. Perfectly [?] and the people are fine. . . . I am becoming most vigorous again, played hockey a day or so ago, [no] goal however for I am rather short-winded still. . . . I surely am glad to get away from that place at Tottenham.”78

On October 27, 1918, Read wrote that “I left Lingfield to-day, discharged from hospital, and I feel like a lost soul. There, everything was arranged for you, and I was so much in the habit, that it seems most peculiar to be on my own again. Lingfield was very fine. . . . I am starting to-day on two weeks leave. Am going to spend some of it in Liverpool and a few days with the Buckleys. Also expect to go to Newmarket to the races.” On the last day of his leave, the day before the armistice, Read was in Liverpool at the Wilkies, and about to depart for London: “What sort of duty I will get I don’t know, but it seems as if the war is practically over. . . . I hope to get back to France for I do not want to spend the winter in Eng., the climate is hard on an old man.”

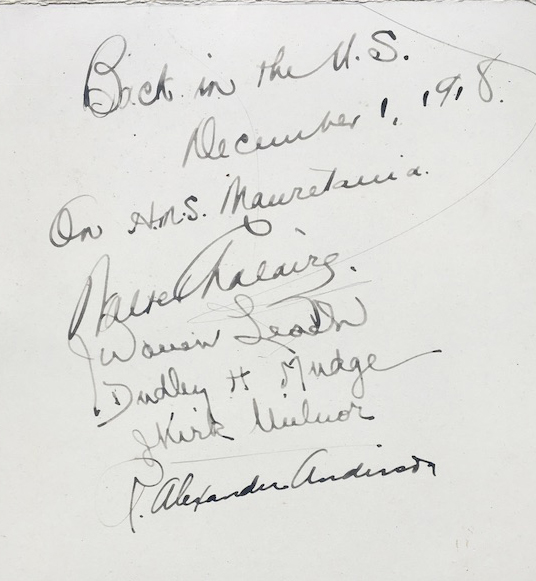

But the war was over, and Read returned to the U.S. Like a number of other second Oxford detachment men who were in England when the war ended, Read was able to leave from Liverpool on November 25, 1918, on the Mauretania.79 He kept a ship’s menu on the back of which he wrote “Back in the U.S. December 1, 1918. On H.M.S. Mauretania,” below which are the signatures of fellow passengers and second Oxford detachment members Walter Chalaire, John Warren Leach, Dudley Hersey Mudge, Joseph Kirkbride Milnor, and Anderson.

There was much fanfare when the Mauretania arrived at Hoboken, as she carried the first American troops and aviators to come back from Europe after the war.

Read returned to Sudbrook Park, Maryland, and worked in the lumber and fencing industries. He is remembered with great affection by his children and grandchildren.

mrsmcq October 24, 2022

Notes

(For complete bibliographic entries, please consult the list of works and web pages cited.)

1 For Read’s place and date of birth, see the entry for him in Maryland War Records Commission, Maryland in the World War, 1917–1919; I have not found a 1917 draft registration for him. For his place and date of death, see “Francis Kinloch Read.” The photo is a detail from Read’s ground school class photo.

2 See, for example, Heyward, The Genealogy of the Pendarvis-Bedon Families of South Carolina, 1670-1900; Chisholm, Chisholm Genealogy; Manigault and Prioleau, Register of Huguenots.

3 On Read’s father see Hull and Hale, Coal Men of America, p. 149; other information on Read’s family is taken from documents available at Ancestry.com.

4 Chisholm, Chisholm Genealogy, p. 75, has entries for two sons who died in infancy.

5 Johns Hopkins University, Preliminary Register of The Johns Hopkins University 1912–13, p. 60; Brown, Johns Hopkins Half-Century Directory, p. 292.

6 Communication from Anne C. R. Leslie (a granddaughter of Read).

7 Roster of the First Training Regiment (Plattsburg), p. 55.

8 “Alumni in Maryland Militia.”

9 Hooper, Somewhere in France, letter of January 8, 1918; and see the entry for Read in Maryland War Records Commission, Maryland in the World War, 1917–1919.

10 Read, letter of [August 4], 1917, to his mother. All of Read’s letters cited are from Read, Letters, papers and photos, and all, unless otherwise noted, are to his mother, Anne Cleland Smith Read. Although this letter is simply headed “Saturday,” Read’s account of the weather and his remark that “I only have three weeks more” make it possible to provide a date. Joseph Sweetman Ames was a professor of physics at Hopkins and involved in air warfare planning.

11 Read, letter of July 29, 1917.

12 Various explanations have been offered for the change of plans; see, for example, those supplied by Hamilton Hadley on p. 4 (286) of “Foreign Aviation Detachments,” by Geoffrey Dwyer on p. 2 of “Report on Air Service Flying Training Department in England,” and by Claude E. Duncan as recorded in Sloan and Hocutt, “The Real Italian Detachment,” p. 44.

13 Read, letter of October 7, 1917.

14 Ibid.

15 Read, letter of October 14, 1917.

16 Read, letter of October 29, 1917.

17 Read is fourth from the right in the fourth row from the bottom.

18 Read, letter of November 4, 1917.

19 Read, letters of November 10 and 17, 1917. Rex, World War I Diary, entry for November 8, 1917, notes that “Saturday some of us are going to run with the Harrowby beagles”; this would apparently involve following the dogs on foot, rather than on horseback.

20 Read, letter of November 23, 1917 (in anticipation of Thanksgiving, which fell on November 29, 1917).

21 Read, pilot’s flying log book. Unless otherwise noted, information about Read’s flight training is based on this log book.

22 Read is not unusual in leaving off the prefix letters on planes’ serial numbers; the letters can be supplied by consulting Robertson, British Military Aircraft Serials 1878–1987.

23 Letter of December 19, 1917, excerpted and published in “Tells of Bird Man’s Life.” The name of the place “about 15 miles away” (Cambridge?) was presumably removed by the censor. See Read’s letter of January 12, 1918, to his sister Mary Middleton Read for his reaction to the publication of his “private correspondence.”

24 Letter of December 29, 1917, excerpted and published in “Tells of Bird Man’s Life.”

25 See “Moundsmere Manor (Historic England),” and documents available at Ancestry.com related to the Buckleys.

26 In his letter of November 4, 1917, to his mother, Read gives her Mr. Buckley’s address, apparently in response to her inquiry, which suggests prior acquaintance.

27 His third instructor may have been John Robert Piggott, later of 74 Squadron, although Piggott’s R.A.F. service record indicates that he was at No. 54 T.S. at this time. See The National Archives (United Kingdom), Royal Air Force officers’ service records 1918–1919, record for John Robert Piggott. Comparisons of photos of “Pigot” and of John Robert Piggott help establish that they were the same person.

28 Read, letter of November 10, 1917. Sissie is perhaps an aunt.

29 Read, letter of January 27, 1918; letter of March 3, 1918 to his uncle Cleland Kinloch Smith.

30 See Mrs. J. W. Jeudwine’s letter of February 28, 1918, to Read’s mother in Read, Letters, papers, and photos; and Read’s letters, passim,

31 “Miss Emily B.[sic] Graves Writes of London in War Time”; this is mainly a transcription of letters written by Anna M. Graves to her sister Emily E. Graves.

32 Barksdale, “The Diary of Lt. Eugene Hoy Barksdale 1917–1918,” entry for January 29, 1918. Grider, also at London Colney, also mentions the incident, although he does not name Read; see Grider and Jacobs, Marse John Goes to War, p. 76. The plane may have been Avro C4481, in which Read flew with Captain Pentland; it was struck off charge on January 31, 1918 (see the record for this plane at Pentland, Royal Flying Corps).

33 Read, letter of March 1, 1918, to his father.

34 In Read’s log book the landing site appears first as “Fasby Farm,” then as “Folly Farm.”

35 I should note that Read records both solo / dual “to date” and “total time in the air”; the distinction is unclear to me, although the latter may reflect non-instructional flying. I assume that the former number is the one relevant for graduation.

36 Cablegrams 694-S (March 7, 1918) and 936-R (March 17, 1918). See also Read’s letter of March 1, 1918, to his Uncle Cleland, where he remarks that he has done enough for his commission.

37 Hooper, Somewhere in France, letter of March 31, 1918.

38 Ibid., letter of March 20, 1918.

39 Ibid., letter of March 22, 1918.

40 Read, letter of March 31, 1918; although clearly with Hooper at Carleton House, Read used Wellington House stationery.

41 Hooper, Somewhere in France, letter of April 3, 1918.

42 Read, letter of April 4, 1918, to his uncle Cleland

42a There are two photos of Read in this plane on p. 40 of Doyle, “War Birds Pictorial.”

43 From the remarks column of Read’s log book.

44 This plane does not appear subsequently in either Read’s or Hooper’s log book, which suggests it was no longer in service. The entry for this serial number at Pentland, Royal Flying Corps, provides no information. When Read finished training and ferrying, he made a list in his log book of the planes he flew; relative to Spads, he noted “1 Written off. Forced landing.”

45 See the relevant entries in their log books. On the plane, see, for example, Leaman, “Captured German Aircraft,” p. 83.

45a Doyle, “War Birds Pictorial,” p. 39.

46 Hooper, Somewhere in France, letter of April 19, 1918.

47 Read, letter of April 28, 1918, to his sister Anne Cleland Read Murray.

48 Hooper, Somewhere in France, letter of April 21, 1918.

49 Ibid.

50 Ibid., letter of April 26, 1918.

51 Read, letter of May 10, 1918.

52 Hooper, Somewhere in France, letter of May 9, 1918, continued on May 11, 1918.

53 Read, letter of May 13, 1918.

54 Read, letter of May 18, 1918.

55 Read, letter of June 4 (?), 1918. (An initial transcription gives a date of June 14, 1918, which must be incorrect.)

56 Reproduced on p. 43 of Doyle, “War Birds Pictorial.” The caption identifies one man as (Leonard Joseph) Desson, but Desson was already at No. 209 Squadron; I suspect this man is actually Watts.

57 Read, letter of June 13, 1918.

58 “Lieut. F K Read USAS.”

59 On No. 60 Squadron, see Warne, “60 Squadron”; Scott, Sixty Squadron, R.A.F., and the relevant entry in Philpott, The Birth of the Royal Air Force.

60 This passage from Winslow’s diary is transcribed on p. 319 of Revell, High in the Empty Blue.

61 Read, letter of June 16, 1918.

62 See the listing of 60 Squadron officers and aircrew members compiled by Warne on pp. 128–31 of part 3 of his “60 Squadron: A Detailed History.” Warne appears to have been misinformed regarding the nationality of Henry Eardley Wilmot Bryning, who was British, not American.

63 60 Squadron R.F.C. Record book. Most of the information on 60 Squadron’s patrols is taken from the record book, unless otherwise noted.

64 Read, letter of June 20, 1918.

65 Ibid.

66 Revell, High in the Empty Blue, pp. 309–10.

67 On Parry, see Revell, High in the Empty Blue, p. 320; the 60 Squadron record book shows Parry making a practice flight on July 3, 1918.

68 See Warne, “60 Squadron,” p. 123; see Heater, “Americans on Day Bombing with the Independent Air Force – Royal Air Force,” p. 117, on the rule and the two-week rule for Americans; also, Read and Roland, Camel Drivers, p. 35. I should mention that on this patrol Harold Buckley, assigned to 60 Squadron on June 3, 1918, is also described as “visiting lines.”

69 Saunders’s combat report in Combat Reports: 60 Squadron.

70 This is among the documents in Read, Letters, papers, and photos. The note is signed “Pat,” which was Saunders’s nickname (probably inspired by his Irish background; see the chapter on Saunders in Gleeson, Irish Aces). The Major was probably the C.O. of 60 Squadron, Barry Fitzgerald Moore; the Colonel was probably Patrick Henry Lyon Playfair, C.O. of the 13th Wing.

71 Read, letter of July 4, 1918. I have not been able to account for the discrepancy between Saunders’s description of the dive (7,000 feet) and Read’s (12,000 feet).

72 “Lieut. Read Wounded”; “Lieutenant Read Improved.”

73 “Lieutenant Read Improved.”

74 The Buckley cable, dated July 16, 1918, and Read’s father’s letter to him (“immense relief”), dated July 17, 1918, are in Read, Letters, papers, and photos

75 Read, letter of July 19, 1918.

76 Read, letter of July 26, 1918; letter dated July 27, 1918, from Thayer to Read’s mother in Read, Letters, papers, and photos.

77 Read mentions that the hospital was in Tottenham in his letter of August [sic; sc. October] 7, 1918; Grace R. Osler, in a letter to Read dated October 8, 1918, (in Read, Letters, papers, and photos) remarks that Thayer “wired about your being at Base 29.”

78 Read dated this letter “Monday Aug. 7th, 1918,” but content and context make clear that it was written on October 7, 1918.

79 War Department, Office of the Quartermaster General, Army Transport Service, Lists of Incoming Passengers, 1917 – 1938, Passenger list for casual officers, Air Service, on Mauretania.