(La Prairie, Wisconsin, September 16, 1894 – Venice, California, October 6, 1969).1

Oxford and Grantham ✯ Elmswell & No. 75 H.D. ✯ Amesbury ✯ Turnberry, Chattis Hill ✯ France & No. 55 Squadron I.A.F.

George Clark Sherman’s maternal grandfather, David Clark, was born on a farm in Aberdeenshire and emigrated with his parents and siblings to the U.S. in about 1859; the family settled in Wisconsin, where they resumed farming. David Clark’s wife was also of Scottish descent, but born in Wisconsin. Their daughter, Isabella Ellen (Nellie) Clark, married William Tecumseh Sherman in 1890. The latter, descended from Rhode Island Shermans, farmed land in La Prairie, outside Janesville. The three children of the marriage, two sisters and their younger brother, George Clark Sherman, were born in La Prairie.2

Sherman attended schools in Janesville. He played football at Janesville High School and was president of his class of 1913.3 He apparently graduated or left early, because in the autumn of 1912 he entered St. John’s Military Academy, a private college preparatory school in Delafield, Wisconsin.4 He excelled at football as well as academically and in the military course, graduating in 1914.5 His father had died in the autumn of the previous year, and this may have influenced Sherman’s decision not to attend university but instead to remain in Janesville, where he worked as a clerk in a boot shop.6 In 1916 he joined the newly formed Janesville Wisconsin National Guard unit and was appointed quartermaster sergeant.7 He was apparently not among those Wisconsin National Guard members who went to Texas in connection with the Mexican Punitive Expedition.8

In the spring of 1917 Sherman began the R.O.T.C. course at Fort Sheridan in Illinois. In mid-July, after three months of training, he was offered the choice of a commission in the infantry or a transfer to aviation.9 He chose the latter and was soon enrolled in ground school at the School of Military Aeronautics at the University of Illinois at Champaign

Sherman’s class of about thirty men graduated September 1, 1917.10 Most of them, including Sherman, chose or were chosen to go to Italy for flying training and were thus among the 150 men of the “Italian detachment” who sailed from New York for Europe on September 18, 1917, on the Carmania. While on board, Sherman wrote an account of the voyage in a letter to his mother that was posted in England. It arrived with holes where the censor had cut out place names and other sensitive information and was published in the Janesville Daily Gazette of October 20, 1917.

I am out at sea having a wonderful time and grand experience. . . . [T]he food accommodations and everything is fine. Our routine for the day is about as follows: Breakfast, 9:00 a.m.; Italian class, 10 to 11 a.m.; physical exercises, 11:30 to 12 m.; lunch, 1:30; Italian class again from 3 to 4 p.m.; life boat drill, 4:15; and dinner at 7:15. All the rest of the time we can do what we like—play cards, shuffleboard, read, or anything. . . . In the evening after dinner we generally gather in the salon and have entertainments of some nature, singing, etc. There are some fine singers and good musicians with us. Albert Spalding, the famous violinist is with us, and it sure is a treat to hear him play—he is a wizard. Yesterday (Friday [September 28, 1917]) a submarine watch was started and we fellows have to take turns night and day watching with glasses for submarines. While going through the “danger zone” we have to wear our life belts all the time. Today (Saturday) our convoy met us [censored] and so now we are traveling along reasonably safe. I should judge we are about five hundred miles from land.11

In addition to Spalding, Fiorello La Guardia was on board, and it was he who was teaching the cadets Italian.

Oxford and Grantham

The Carmania docked at Liverpool on October 2, 1917. Almost immediately the men learned that plans had changed and that they would not go on to Italy, but would remain in England to attend ground school (again) at the Royal Flying Corps’s No. 2 School of Military Aeronautics at Oxford University. The “Italian detachment” thus became the “second Oxford detachment” (another detachment of American cadets having arrived a month previously).

The men took a train to Oxford and were assigned to various colleges for their first night. The next day, according to Jesse Frank Campbell, who had been with Sherman at Fort Sheridan, they were reassigned. Campbell “was transported to Queens College today. 60 were sent to Queens and 90 to Christs. Ed Moore, George Sherman, and myself have a large room on the fourth floor.”12

Having arrived mid-week, the men were not expected to begin classes until the following Monday, which left them free to settle in and explore. “Sherm” and Jesse Campbell “walked about the town” and had their “first experience of English rain and mist today and it certainly kept up to its reputation.”13 When they did start classes on Monday, October 8, 1917, many of the men were put out at the prospect of repeating what they had already covered in the States, but they soon came to appreciate being taught by officers who had had actual flying experience at the front.

Jesse Campbell noted in his diary on October 21, 1917, that he, Ed Moore, and Sherman “went out to Cox’s for dinner and had a fine time.” The next day they “were moved from Queens to Exeter College today. We drew a room on the third floor again. . . . We have a little better room but no fire. All the American Cadets are together again.” The change of lodgings had been precipitated by bibulous celebrations on the 20th by some members of both detachments, which greatly annoyed the British authorities, who thought it best to confine all the Americans to a single college.14

There was relief when the detachment members learned that what had initially been described as a six-week course would actually be four. Nevertheless, disappointment followed for most of them. Twenty men were sent at the beginning of November to Stamford to begin flying, but the remainder, including Sherman, were sent from Oxford to Harrowby Camp, a machine gunnery school near Grantham in Lincolnshire. As Parr Hooper, also ordered to Grantham, remarked, “It looks like we got sent here because there was no other place to send us to—playing for time.”15

The first two weeks at Harrowby Camp were devoted to learning about and practicing on the Vickers machine gun. On days off, the men explored the surrounding countryside and towns. Writing home on November 11, 1917, Ed Moore reported that “Sherman and I went to Nottingham yesterday. . . . Quite a treat to be in a real town for awhile. We met several Canadian and other British officers.”16

In mid-November fifty of the men at Grantham were posted to R.F.C. training squadrons, including Jesse Campbell, who wrote that “I hate to leave Sherman and Ed Moore but I suppose it must come sooner or later anyways.”17 Moore and Sherman remained at Grantham through Thanksgiving and finished the second two-week course, this time on the Lewis machine gun. Finally, on December 3, 1917, they and all the remaining members of the second Oxford detachment were posted to squadrons.

Elmswell and No. 75 H.D. Squadron

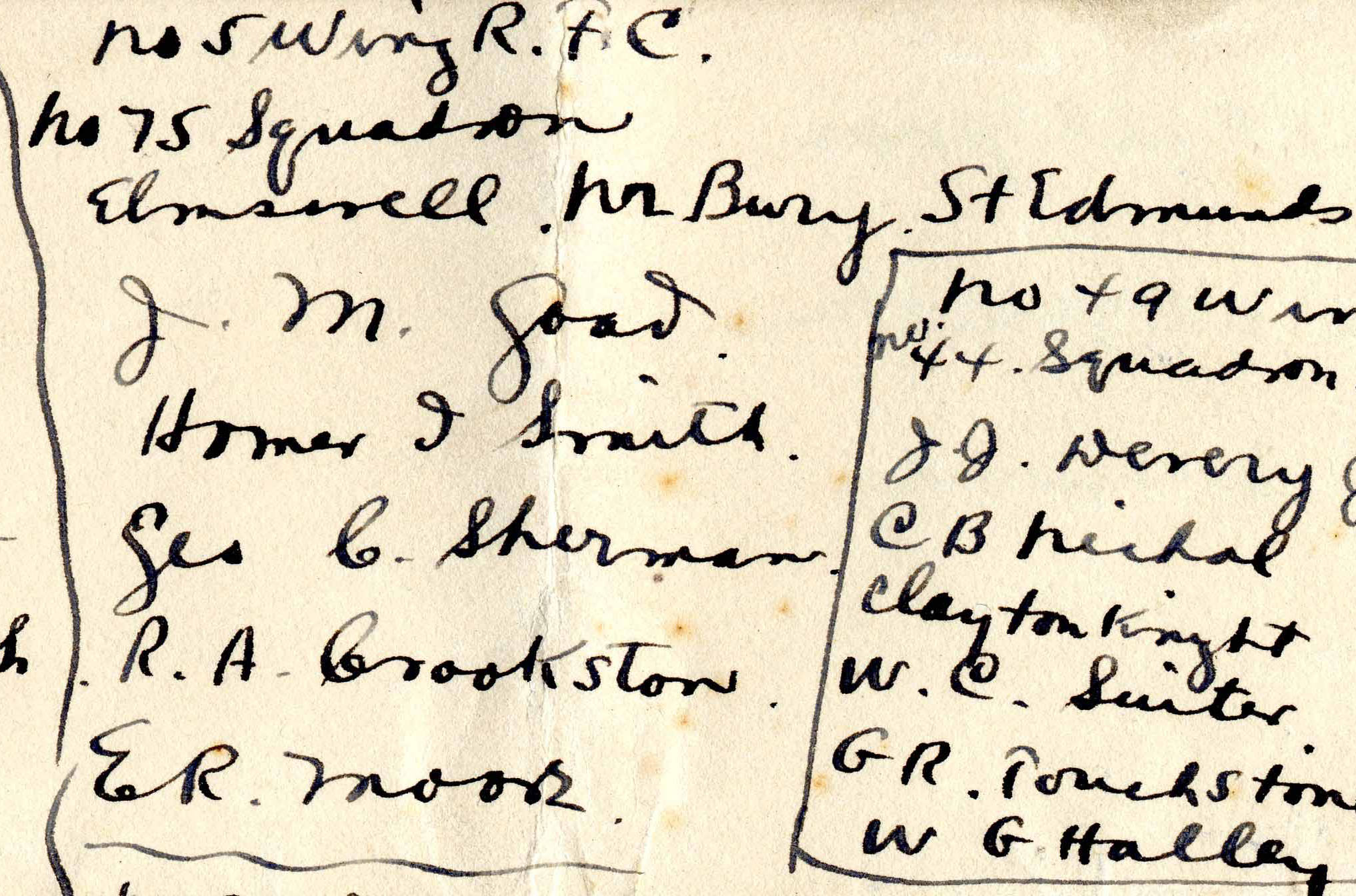

Sherman was one of five sent to No. 75 Home Defense Squadron, which was located near Elmswell in Suffolk. The other four, all from the same Illinois S.M.A. ground school class, were Ralf Andrews Crookston, John Marion Goad, Ed Moore, and Homer Ireland Smith.18 The men were billeted in nearby Stowmarket, at the Fox Hotel. Sherman wrote home that “A car calls for us every morning at 8:30 and brings us back every evening. The people at the hotel are mighty nice and do everything they can to make us comfortable.”19

It appears that winter weather limited flying during much of December and early January. Jesse Campbell, stationed for a time at nearby Thetford, recorded a number of days of high wind and rain in his diary.

Sherman spent a quiet Christmas at Elmswell. On New Year’s eve, “The five of us Americans bought an eight-pound turkey for $5.00 and had the people at the hotel prepare it for us. We had a real feed—there was nothing left but the bones when we were through.”20

During the second week of January 1918, as Sherman wrote his mother, it had “been snowing and no chance to fly for three or four days so Smith . . . and I decided to spend a couple of days [in London] and see part of the city. We stayed at the Savoy Hotel and had a room that looked like it might have belonged to King George. We saw four shows—‘Chu Chin Chow,’ ‘Cheep,’ ‘Around the Map’ and ‘Here and There.’ They were very clever plays and much enjoyed by both of us. We met quite a number of our bunch that came over with us up to [sic] London.”21 Among those they saw was Jesse Campbell, who reported that “I was very glad to see [Sherman and Smith] again and exchange flying experiences. They are at a good place at Elmswell at a H.D. squadron (B.E.’s) but don’t get much flying.”22

Things appear to have picked up after the London visit. On January 12, 1918, Sherman was reporting that “I’m getting along flying very good. The instructor said today that I was a fiend for it. Can’t keep me on the ground when there is a machine around. Oh, it is wonderful sport. I’m wild about it.”23 Ed Moore was similarly enthusiastic: “George and I would live in the air if we could get a machine whenever we wanted it,” and notes that “We are flying ‘Querks’ [sic] and ‘Soup kitchens.’ Fortunately George and I are on the former, which received its name on the strength of its resemblance to the Australian bird, the quirk, which can only fly a short distance. They land at 60 miles an hour and are fairly stable, moderately light on the controls.”24 Moore’s “Querks” were presumably 75 Squadron’s B.E.2e’s, which could be fitted with dual controls.25 Sherman closes his letter of January 12, 1918, with the remark that “Tomorrow a couple of us are going up for ceiling test in a B.E. machine—that is, we are going up just as high as it will go, which will be about 18,000 feet.”26 Sherman was almost certainly anticipating going up as a passenger with one of the squadron’s experienced pilots, not piloting himself to this altitude at this point in his training.

Amesbury

There is no direct documentation of Sherman’s next posting, but a number of second Oxford detachment men, including Ed Moore, were sent to new training sites on about January 26, 1918. It is likely that Sherman was among them and that, like Moore, he was posted to No. 6 Training Depot Station at Boscombe Down near Amesbury in Wiltshire. Moore mentions Sherman’s presence at 6 T.D.S. in a letter from March 31, 1918, and Sherman was at Amesbury when he was placed on active duty.27 It would have been evident at this point in Moore’s training, and presumably also Sherman’s, that he had been selected to fly two-seater planes and would be training as an observation or a bomber pilot.

In a letter home dated January 27, 1918, Ed Moore writes that “I have just been transferred to this place but will continue on the same type of machine I used at the other place, except to do some formation flying and bombing in some clumsy old box kites the name of which I may as well omit.” Charles Louis Heater, also at Amesbury, wrote that “Our first sight of the elementary D.H. 6 prompted a look to see who was holding the string, for they looked like box kites in a strong wind.”28 Moore continues: “Then, too, there will be more classes in photography and bombing—not to mention more gunnery and wireless. . . . I am looking forward to a number of cross country flights, only short ones, under a hundred miles, but very interesting.”29

For a time, Sherman and Ed Moore were probably in lodgings in Amesbury, but by the end of March, as Moore writes, “We are under canvas again. The permanent quarters are not completed. Sherman and I have a small tent together. We bought an oil stove and a few additional cooking utensils, so it is not so bad after all.”30

Sherman’s training evidently moved along at a smart pace. By early March 1918, he had completed enough hours to be recommended for his commission. Pershing’s cable forwarding the recommendation to Washington is dated March 13, 1918; the confirming cable is dated March 30, 1918, and on April 8, 1918, Sherman was placed on active duty.31

In a letter dated April 7, 1918, Ed Moore gives an account of a cross-country flight he undertook with three others: “Four of my bunch, including myself, planned a 350-mile across country last Tuesday [April 2, 1918]. [Phillips Merrill] Payson and I made the course, Sherman got lost in the clouds about half an hour from home on the start and [Robert Jenkins] Griffith got lost over Ipswich. The most distant point was Elmswell. It took us five hours and a half.”32 Unfortunately, perhaps out of censorship concerns, Ed Moore does not indicate what type of plane they were flying, although he does mention having recently been flying service machines; it is possible that they were already at this time flying DH.4s.

Also around this time Sherman and Ed Moore completed the various tests required for graduation from this stage of R.F.C. / R.A.F. training and were awarded some leave.33 Apropos of this, Moore wrote that “George is going to Dublin, but I think there is a quiet spot and a few friends in northern England for me.”34

A Janesville newspaper article about Sherman’s commission also paraphrases “a recent letter” in which Sherman wrote “of dropping bombs, real ones, and making six out of eight attempts. He also wrote of an experience while flying when he was lost in the clouds and had to steer by compass being in the air in more ways than one for four hours.”35 This suggests that Sherman may have been taking instruction at the No. 1 School of Navigation and Bomb Dropping at Stonehenge, to the west of Amesbury, although I have not found official documentation of his presence there.

Turnberry, Chattis Hill

After finishing up at Amesbury, Sherman was posted to the No. 1 School of Aerial Fighting and Gunnery (which became the No. 1 Fighting School on May 29, 1918) at Turnberry on the west coast of Scotland to do his final advanced training.36 Ed Moore, Heater, and Kenneth MacLean Cunningham were posted there at or around the same time. On June 2, 1918, Moore wrote from Turnberry that “This has been a delightful change, both from the standpoint of military training and personal enjoyment. From tents to what in peace times is a flourishing pleasure resort, an immense hotel which faces the sea, situated on a fairly high hill, terraces dotted with flower beds and shrubbery, tennis-courts, croquet grounds, on down to a very famous golf course. . . .”37 Sherman, writing the same day, remarked that “I did quite a bit of flying this past week. The weather is ideal here all the time. The Colonel [Lionel Wilmot Brabazon Rees] let us Americans off Thursday afternoon (Decoration Day [May 30]) and we went into Ayre [sic] and played ball against some American mechanics. Our weekly holiday is from Friday noon until Saturday noon, so Cunningham, Heater and I got permission to be absent Friday morning also and went from Ayre to Glasgow Thursday evening.”38 From there the three men made an outing to Loch Lomond: “It was a beautiful trip. I wouldn’t have missed it for anything.”

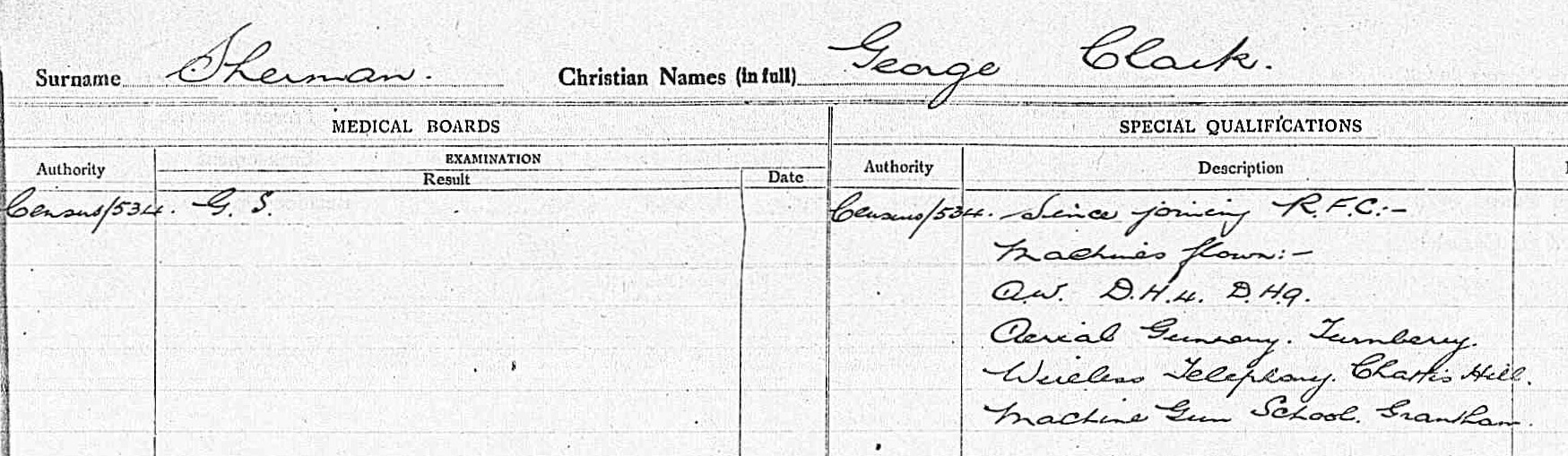

Sherman’s sketchy R.A.F. service record notes that, in addition to his posting at Turnberry, he, like Ed Moore and Heater, was for a time at Chattis Hill (about ten miles east of Boscombe Down), presumably at the Wireless Telephony School.39 He may then, again like Heater and Moore, have put in a stint as a ferry pilot, flying planes from place to place in England and perhaps also to France.

France and No. 55 Squadron I.A.F.

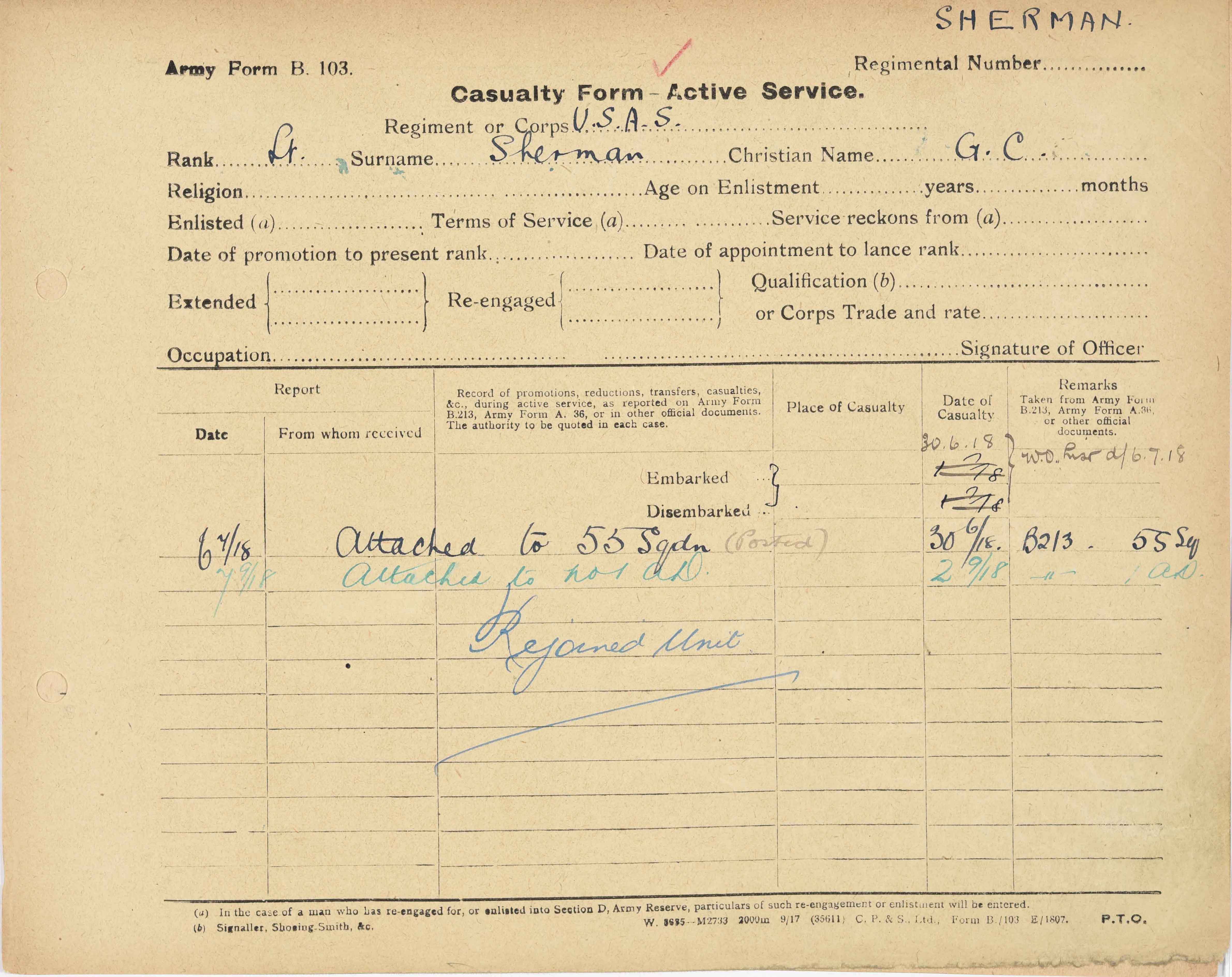

Towards the end of June 1918 Sherman received orders to proceed to France. His casualty form does not provide the date of his crossing, but it was almost certainly on June 29, 1918, in the company of Cunningham, Heater, and Payson.40 Apparently shortly before embarking, the four men, according to Heater, “chanced to meet an RAF pilot who had recently returned. On learning that we were D.H. pilots, he suggested that we request assignment to a D.H.4 squadron that was fitted with Rolls Royce engines. We did so, and were assigned to 55 squadron.”41 The men’s casualty forms indicate that they were all posted to No. 55 Squadron on June 30, 1918.42

No. 55 had been formed as a training squadron in 1916, but in January 1917 was designated a bombing squadron and became the first squadron to be equipped with DH.4s. By early March it was stationed in France, flying bombing and reconnaissance missions.43 When Hugh Trenchard’s Independent Air Force came into being on June 6, 1918, No. 55 was assigned to it. The purpose of the I.A.F.—which initially consisted of Nos. 55, 99, and 104 Squadrons (day bombing), and Nos. 100 and 216 Squadrons (night bombing)—was to carry out long-range bombing of strategic targets within Germany and to operate, as Heater put it, “without the Army having any prior claim to their service except in serious situations.”44 To make it possible for the DH.4s, which as built had an endurance of three and three quarters hours, to achieve the range required by the I.A.F., those of No. 55 Squadron were fitted with an extra gas tank, which made flights of as long as five and a half hours possible.45

Once posted, the four men from the second Oxford detachment destined for 55, along with Philip Dietz, Linn Daicy Merrill, and Horace Palmer Wells, assigned to No. 104 Squadron, set out for Azelot, a few miles south of Nancy, where the I.A.F. day-bombing squadrons were based. Of this journey Heater wrote that “Nine months of training in England should have given the party of American pilots who left for the Independent Air Force on the last of June an idea of the sort of thing they were running into when they got to France, but most of them were unpleasantly surprised when they were bombed the first night in Boulogne, the second in Paris, the third while on their way to their squadrons in tenders, and several succeeding nights after reaching their stations.”46 Writing from Azelot on July 14, 1918, Sherman recounted how “Fritz has been over several times to visit us and has dropped a few ‘pills,’ but he has not done any damage at all. I am getting so that I sleep right through his visits. The anti-aircraft guns do not even disturb me any more.”47

With this letter Sherman enclosed a newspaper clipping about “one of our raids over Coblenz.” According to the newspaper’s accompanying commentary, “There is but little doubt but that Lieutenant Sherman was in this raid which makes it doubly interesting to the people of Janesville.” However, the raid by No. 55 Squadron referred to took place in the early morning of Friday, July 5, 1918, probably just before Sherman and the others arrived at Azelot.48 In any case, new pilots were expected to spend their initial time at the front getting to know the equipment, the squadron, and the area and not to go over the lines until well oriented.49

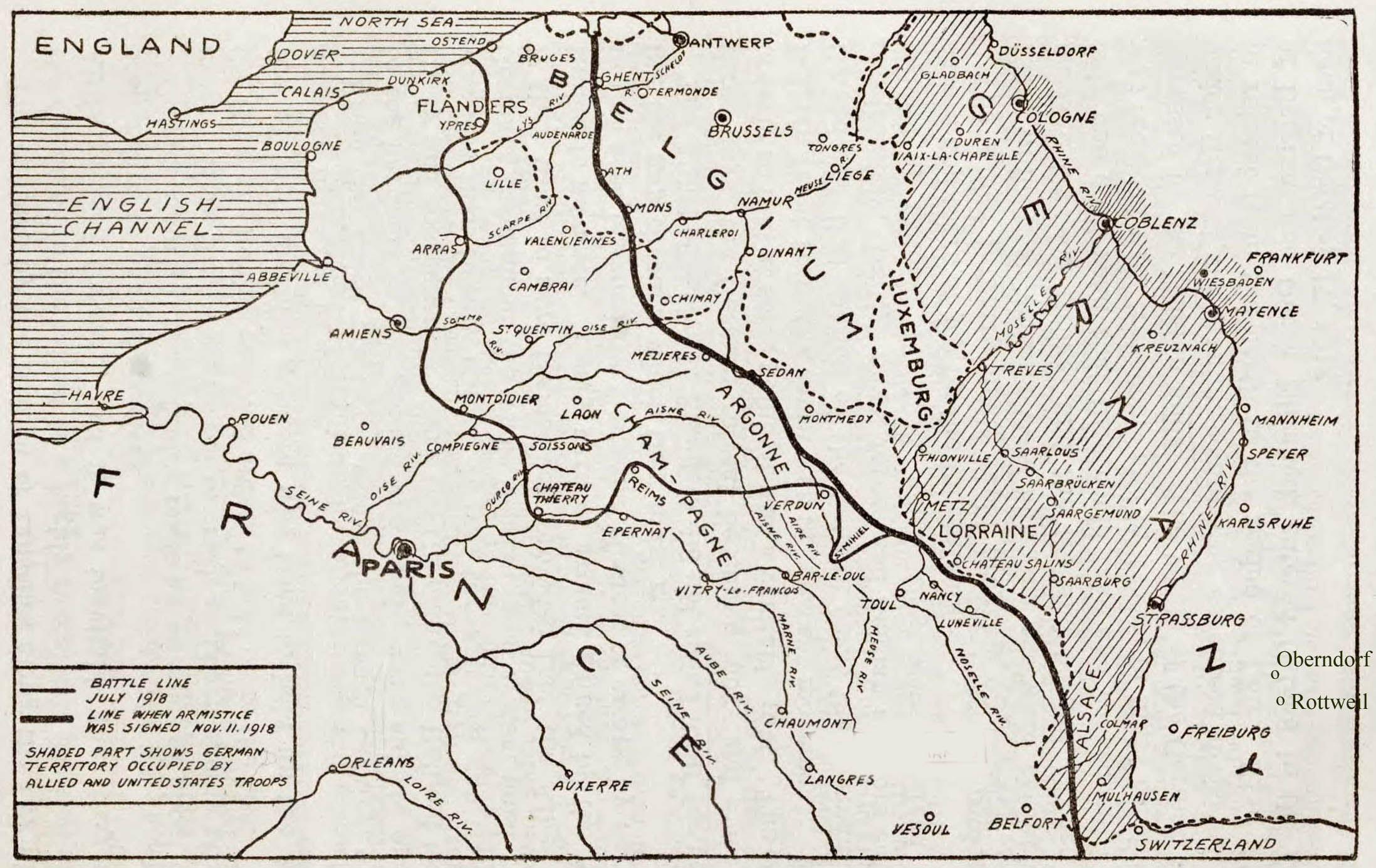

It was just under two weeks after his arrival at 55 Squadron, on July 17, 1918, that Sherman took part in his first raid. The objective was Thionville, an important railway station for the Germans, one which had been the repeated target of the I.A.F. since its inception (and of 55 Squadron prior to that). About fifty miles due north of Azelot, it was, unlike Koblenz, well within the range of the DH.9s of No. 99 Squadron, and the mission was a joint one for 55 and 99 Squadrons.

The planes of 55 took off at 9:50, fifteen minutes after those of 99.50 As usual, the “twelve machines flew in two formations of six machines each, the two formations acting as protection for each other and keeping the Hun more or less at a loss as to the best method of attack. A flight commander would lead the raid, taking the first formation of six machines, and an old experienced pilot leading the second formation of six machines.”51 Heater noted that “The position of a new pilot in a formation . . . was always certain to be one of the rear positions, not that this position was any safer to fly than any other but it was less dangerous to the rest of the formation if the position was not flown correctly”52 Sherman, with observer William Edward Baker, apparently occupied this rear position that day in the first formation, which was led by Benjamin James Silly, while Heater, on this, his second mission, was apparently in the same position in the other formation.53

Rennles describes the two formations heading initially northwest while gaining altitude and then, flying at 12,500 feet, crossing the lines at Fresnes (presumably Fresnes-au-Mont near St. Mihiel). Turning east, they flew over Conflans-en-Jarnisy and on to Thionville where, from 13,500 feet, they dropped their bombs. The return involved heading southeast and flying over Boulay-en-Moselle and then back southwest to cross the lines at Nomeny. There was “moderate but accurate fire” near Fresnes on the outward journey, and there was a running fight with five enemy aircraft on the first leg of the return. The planes arrived safely back at Azelot at 12:45.

At some unspecified point, Sherman was, according to Heater, “struck in the back by a piece of shrapnel from an anti-aircraft shell, his wound did not appear serious so he did not go to a hospital and continued work with the squadron.”54 Presumably because the injury did not seem serious, no casualty card was generated, and the incident does not appear in Rennles’s account of the raid. Nevertheless, word of the injury reached Janesville and merited a brief mention in the local newspaper.55

Sherman did not take part in No. 55 Squadron’s next mission on July 19, 1918, but did fly the missions that No. 55 Squadron undertook in conjunction with No. 99 Squadron on the 20th and 22nd. On both missions Sherman was again apparently at the back of the formation and in the same formation as Heater, and on both missions Sherman’s observer was Gerald Capito Smith, an American from Baltimore who had attended St. John’s in Annapolis before going into journalism and then the aviation service.56

On both the 20th and the 22nd the intended target was the Mercedes aero engine works at Untertürkheim near Stuttgart. On the 20th Frederick Williams, leading the first formation—Sherman and Heater were in the second—headed southeast to cross the lines at Saint-Dié-des-Vosges at 14,000 feet. Once turned east-northeast to cross the Rhine and fly towards Stuttgart, a strong headwind prompted Williams to seek a closer objective, a munitions factory near Oberndorf. After dropping their bombs and turning for home, the planes of the first formation came under fierce attack.57 Eight planes arrived back at Azelot at 9:12 a.m.—one plane from the second formation having returned early due to engine trouble; three planes from the first did not return.

On July 22, 1918, Sherman, along with Heater, was in the first formation, led by Silly; the mission commenced at 7:30 a.m., and once again headed southeast, this time crossing the lines at Markirch (Sainte-Marie-aux-Mines). As on the 20th, high winds prompted the leader to change the objective, this time choosing instead to fly due east to Rottweil with its powder works. On the return journey enemy planes were spotted, and “a long-range running fight ensued, the enemy scouts keeping their distance as the formations turned west over Villingen towards Freiburg.”58 But for the planes that had had to return early because of engine trouble, all landed at Azelot safely at 11:35.

Heater, writing presumably after, but not long after, the war, provided an account of Sherman’s experience, on one of these missions, that does not figure in other sources: “On [Sherman’s] second [sic] raid his motor went bad over the objective, which was Rottweil, an important powder factory just south of Stuttgart, and he lagged behind all the way home. He had a new observer too, an American, who was very badly scared and forgot all about trying to find the way home or anything else except to shoot wildly, but fortunately the leader of the second formation saw Sherman’s plight and kept over him until we came in sight of our lines. Incidentally, after this trip, the observer found that his heart was weak and he quit flying to return to Tours as an instructor.”59

There are several obvious problems with this account, which appears to conflate details from the missions of the 20th and the 22nd, but, given that Heater was on both occasions in the same formation with Sherman and Smith, it seems likely that the substance is accurate. Smith, in any case, does not figure among observers listed by Rennles in any of the subsequent missions flown by 55. His casualty form shows him returning to American Aviation HQ on August 28, 1918, and he is listed among the officers at the Second Aviation Instruction Center at Tours at the end of the war.60

A period of bad weather ensued, and No. 55 Squadron did not fly any further missions until July 30, 1918. Sherman took part in his next (fourth) mission on the following day, when the objective was to be the almost impossibly distant Cologne. Sherman and Heater were assigned to the first formation led by Silly; they were now both towards the front of the formation. Sherman’s new observer was Norman Wallace, apparently on his first mission. Encountering high winds and clouds over Trèves (Trier), Silly diverted the flights to Koblenz where they dropped their bombs. It is notable that on the return journey the formations flew for a time at 17,000 feet. They arrived safely back at the aerodrome at 10:20 a.m., a full five hours after take off.

Sherman did not fly the next day, when No. 55 Squadron once again unsuccessfully attempted to reach Cologne, but did take part in the next mission, after a period of bad weather, on August 8, 1918. On this occasion, all four of the American pilots assigned to No. 55 Squadron were part of the mission: Sherman (with Wallace), Heater, and Cunningham were in the first formation, led by Silly, and Payson was in the second. They took off at 10:03 a.m.; the target was Rombach (Rombas), about eight miles south-southwest of Thionville. As on Sherman’s first mission, the planes flew initially towards Fresnes and then headed east to Conflans; from there they could, when clouds permitted, follow the railway line to Rombas, which they reached and bombed at 12:20 p.m. On the return journey they were pursued by German scouts, but were able to cross the lines at Pont-à-Mousson and return safely to Azelot at 1:30 p.m.

This was Sherman’s fifth and final flight. There is no account of difficulties in either Rennles’s Independent Force or The Official History of No. 55 Bombing Squadron 1916–1924. Heater, however, indicates that Sherman’s performance was being affected by health issues. In his “Americans on Day Bombing,” Heater implies that Sherman’s earlier shrapnel wound was the issue,61 but provides a different and lengthy explanation in his informal account. In the latter he implies that already on the missions when Smith was his observer, Sherman was having problems with his sight:

Sherman was [like Smith with his weak heart] also working under a big handicap, for his eyes were badly out of order somehow, but he kept on until his sixth [sic] show, while raiding Rombach, . . . he turned his machine slightly and came skidding across the formation. He was flying number three position, on the right of the leader and slightly above, I was number two, just across from him; he barely missed the tail of the leader and would have collided with my machine, had I not pulled up and let him go past. He fell out and finally got back into his place in the formation, then the performance was repeated. When we reached home he declared that his slips had not been noticed by him until he had gotten clear across the formation and that even then had had a hard time trying to figure how he had reached there.62

Examined by the squadron medical officer, Sherman was not permitted to continue flying. It appears that he remained with No. 55 in some capacity until August 18, 1918, at which point he was admitted to hospital.63 According to Heater: “Later, after travelling thru most of the base hospitals in the B.E.F., and the A.E.F., as well [Sherman] was finally sent to Clermont as a bombing instructor.”64 Sherman’s name appears on a list of commissioned personnel at the Seventh Aviation Instruction Center at Clermont-Ferrand at the time of the armistice, and there is a brief biography of him in the December 11, 1918, edition of the 7th A.I.C.’s newspaper.65 It appears he also had another assignment, perhaps prior to going to No. 7 A.I.C.: a brief article from early November in the Janesville Daily Gazette states that “. . . Sherman who is now in Paris, France, who has been suffering from an injury to his eyes, is much improved. . . . He has now taken a new position in the wireless telephony, with headquarters in Paris.”66

Sherman was able to set out for the U.S. fairly soon after the war: he sailed from Marseilles on the America on February 10, 1918; among his ship mates was his fellow second Oxford detachment member Andrew Joseph Shannon.67

Sherman returned to Wisconsin and went into business while also being active in the National Guard until his retirement from the Guard in 1959.68

Notes

(For complete bibliographic entries, please consult the list of works and web pages cited.)

1 Sherman’s place and date of birth are taken from Ancestry.com, Wisconsin, U.S., Births and Christenings Index, 1801-1928, record for George Clark Sherman. I should note that Sherman’s draft registration gives Janesville as his place of birth; see Ancestry.com, U.S., World War I Draft Registration Cards, 1917–1918, record for George Clark Sherman. Sherman’s place and date of death are taken from “Southern Wisconsin Obituaries.” The photo is taken from Phoenix, p. 38.

2 Information on Sherman’s family is taken from documents available at Ancestry.com.

3 See Phoenix, pp. 38 and 78.

4 See “Personal Mention” (September 24, 1912).

5 “Military Academy Gives High Honors to George Sherman.”

6 “William T. Sherman of La Prairie Dies”; entry for Sherman in Wright’s Directory of Janesville for 1917.

7 “Second Separate Company W.N.G. is Present Title.”

8 “Local Militiamen Enroute for State Camp This Morning.”

9 “Sherman Turns Down Infantry First Lieut. for Aviation Corps.”

10 “Ground School Graduations [for September 1, 1917].”

11 “Writes of Trip to School in England.”

12 Jesse Campbell, diary entry for October 3, 1917.

13 Jesse Campbell, diary entry for October 4, 1917.

14 The celebrations of the first Oxford detachment and the aftermath are recounted in several diaries, as well as in the October 22, 1917, entry in War Birds.

15 Hooper, Somewhere in France, letter of November 4, 1917.

16 “Letters from Soldiers” (December 13, 1917).

17 Jesse Campbell, diary entry for November 15, 1917.

18 Foss, Papers, “Cadets of Italian Detachment Posted Dec 3rd.”

19 “George Sherman is Taking Rapid Steps in the Flying Game”; the Stowmarket hotel is identified in “Lieutenant Sherman is Anxious to Sail.”

20 “George Sherman is Taking Rapid Steps in the Flying Game.”

21 “George Sherman is Taking Rapid Steps in the Flying Game.”

22 Jesse Campbell, diary entry for January 9, 1918.

23 “George Sherman is Taking Rapid Steps in the Flying Game.”

24 “Letters from Soldiers” (March 14, 1918).

25 Lee, No Parachute, pp. 4–5, writes “Six of us were detailed to ferry B.E.2es to No 2 A.D. I hadn’t flown a Quirk for months, . . .” This is the only primary source reference to a B.E.2e as a “quirk” I have found; there are secondary sources that gloss “quirk” as any training plane (Holmann, “Cabbage crates coming over the briny?”), as a B.E.2 generally, or as a B.E.2c (Hart, Bloody April, Ch. 6). I find no reference besides Moore’s to any World War I plane as a “soup kitchen.” The other planes at 75 H.D. were, according to Jefford, R.A.F. Squadrons, B.E12s and F.E.2b’s; the latter, a two-seater, may have been used for training there and were, perhaps, what Moore was referring to.

26 “George Sherman is Taking Rapid Steps in the Flying Game.”

27 See Ed Moore’s letter in “Letters from Soldiers” (May 23, 1918); Biddle, “Special Orders No. 35.”

28 Heater, quoted in Skinner, “Commanding the 11th,” p. 260.

29 “Letters from Soldiers” (March 14, 1918).

30 “Letters from Soldiers” (May 23, 1918).

31 Cablegrams 726-S and 1008-R; Biddle, “Special Orders No. 35.”

32 “Letters from Soldiers” (May 23, 1918).

33 The Royal Flying Corps became the Royal Air Force on April 1, 1918.

34 “Letters from Soldiers” (May 23, 1918).

35 “George Sherman is Made 1st Lieutenant.”

36 On the names given the training stations at Turnberry and Ayr, see Jeffords, Observers and Navigators, p. 51, and “No 1 Fighting School Turnberry.”

37 “From Trench and Camp” (July 15, 1918).

38 “Lieutenant Sherman is Anxious to Sail.” The ball games with the American mechanics seem to have been a regular feature of life at Ayr; see Hooper, Somewhere in France, letter of April 30, 1918.

39 On the instruction at Chattis Hill, see Jeffords, Observers and Navigators, p. 369.

40 See their casualty forms: “Cunningham, K.M. (Kenneth M.),” “Lieut. C L Heater A S S R C,” “Lieut. P M Payson AS SRC,” and “Lieut. G C Sherman USAS.”

41 Heater, quoted in Skinner, “Commanding the 11th,” p. 261.

42 See casualty forms cited in earlier note.

43 On 55, see Barrass, “No 51 – 55 Squadron Histories.”

44 On the composition of the I.A.F., see Rennles, Independent Force, pp. 6-7; Heater, quoted in Skinner, “Commanding the 11th,” p. 261.

45 See Miller, The Chronicles of 55 Squadron, R.F.C. and R.A.F., p. 65, and Trenchard, [Report on the work of the Independent Air Force], p. 134.

46 Heater, [Informal account], p. 124. Miller, Chronicles of 55 Squadron, p. 74, records that “on the night of Sunday, the 7th [of July 1918], [the enemy] dropped his first bomb on the aerodrome. . . .” Cf. The Official History of No. 55 Bombing Squadron 1916–1924, p. 38 [40].

47 “George Sherman Writes Letter.”

48 See see Skinner, “Commanding the 11th,” p. 262, regarding Heater’s, and thus presumably also Sherman’s, arrival at Azelot on July 5, 1918. See Rennles, Independent Force, pp. 48–49, on the early morning raid on Koblenz on July 5, 1918.

49 Heater, “Americans on Day Bombing with the Independent Air Force – Royal Air Force,” p. 117, claimed that the orientation period was two weeks for Americans, but he himself took part in a raid just eleven days after his arrival.

50 Unless otherwise noted, information about these missions is taken from Rennles, Independent Force. Rennles provides a “Select Bibliography” (p. 211) and an overview of how he went about his research (pp. 10-11), but neither is adequate to allow one to verify sources for particular statements or to determine whether Rennles’s sources might provide additional information.

51 Heater, [Informal account], p. 126.

52 Heater, “Americans on Day Bombing,” p. 118.

53 See the listing of pilots on p. 61 of Rennles, Independent Force, which presumably reflects the pilots’ positions in the formations.

54 Heater, “Americans on Day Bombing,” p. 119. Cf. Heater, [Informal account,] p. 127: “On Sherman’s first raid a piece of shrapnel tore through his monkey suit and gave him a painful cut all across his back, between his shoulders.”

55 “George Sherman Injured.” A later document, “Known Casualties of American Fliers with British Independent Air Forces,” mistakenly gives the date as July 16, 1918.

56 See St. John’s College, Catalogue of St. John’s College Annapolis Maryland for the Academic Year, 1905–1906, p. 10; and Ancestry.com, U.S., World War I Draft Registration Cards, 1917–1918, record for Gerald Capito Smith. The draft card lists his employment at the Evening World.

57 See The Official History of No. 55 Bombing Squadron 1916–1924, p. 39 [41].

58 Rennles, Independent Force, p. 66.

59 Heater, “[Informal account],” p. 127.

60 “Lieut. Gerald Capito-Smith SR CAS.”; “Second Aviation Instruction Center, Tours, France,” p. 70. See “Two Evening World Fighters” for Smith’s account of the raid on Rottweil, and “Decorated by France” regarding his receiving the Croix de Guerre. These and other news stories by Smith make one suspect that his first allegiance was to journalism and a good story rather than to accurate history.

61 Pp. 119–20.

62 P. 127.

63 “American Fliers with the I.A.F.,” p. 133.

64 Heater, [Informal account,] p. 128.

65 “Seventh Aviation Instruction Center, Clermont-Ferrand (Puy-de-Dome), France,” p. 242; “George C. Sherman.”

66 “Personal Mention” (November 7, 1918).

67 Ancestry.com, U.S., Army Transport Service, Passenger Lists, 1910-1939, record for George C Sherman.

68 On Sherman’s post-war occupation, see relevant census records at Ancestry.com; “Gen. Sherman of Guard Retires.”