(Benson, Illinois, December 5, 1890 – Glenview, Illinois, October 1, 1934).1

James Ernest Roth’s grandparents were all born in Germany but emigrated to the U.S. around 1850 and settled in Illinois; both of Roth’s parents were born in that state. His father, Jacob, was for a time a farmer, but at some point after his marriage to Mary Anna Felt in 1877, went into the retail grocery business. The couple had seven children; James Ernest and his twin sister were the youngest.2 James Ernest was baptized “Jacob Ernst”; he was later known as James or Jim, and sometimes as Jacob or Ernest.

Roth appears to have attended Illinois Wesleyan University in Bloomington, not far from where he grew up; I have not found a record of his graduation.3 In 1911 he trained to fly in Chicago and received his pilot’s license in November of that year.4 There are references to Roth in 1914 and 1915 at the Cicero Flying Field just west of Chicago, working with Anthony Stadlman (later one of the founders of Lockheed Aircraft Company) on the construction of planes.5

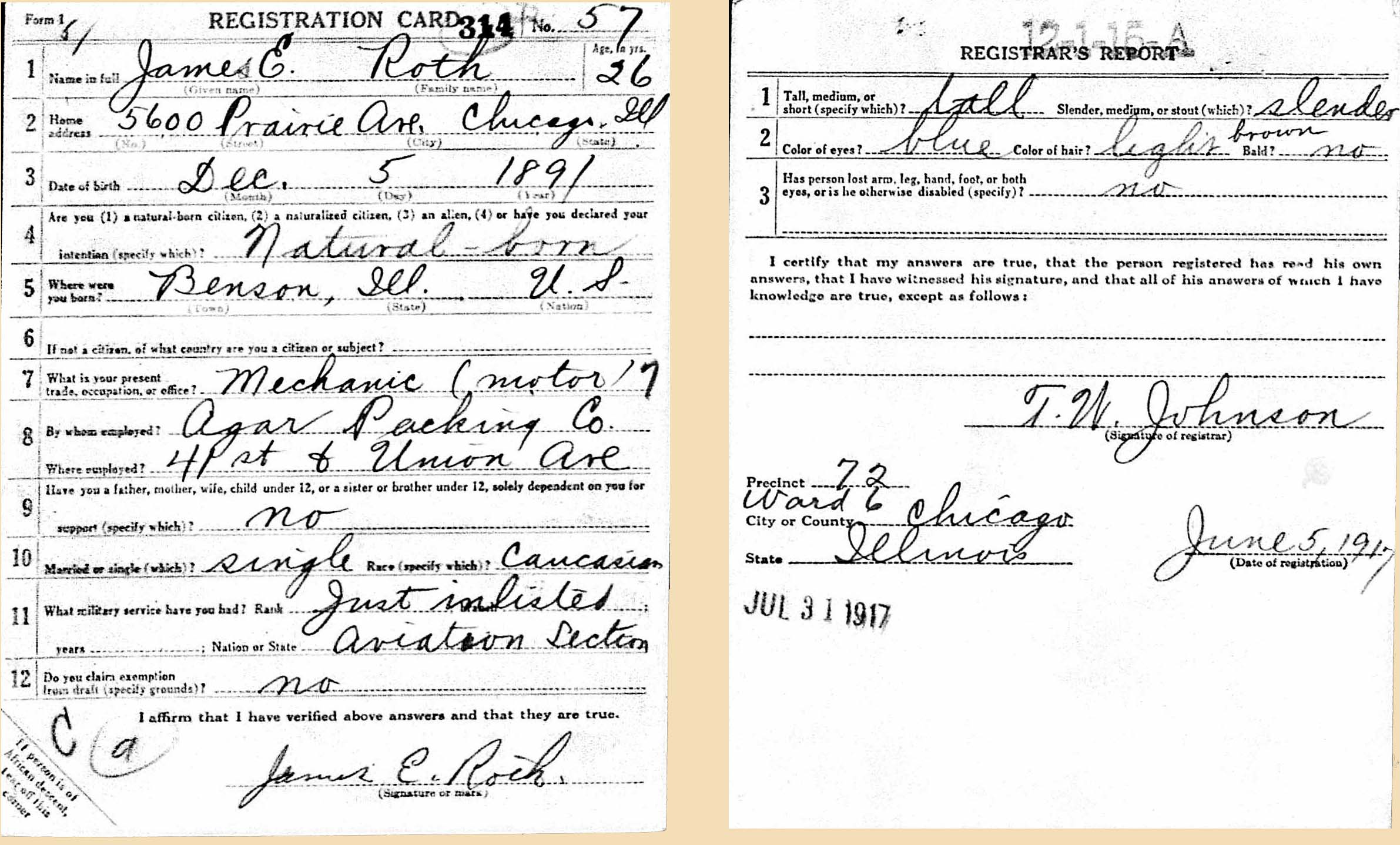

When Roth registered for the draft, he was working as a motor mechanic for Agar Packing Company in Chicago. He noted that he had “just enlisted” in the “Aviation Section.”6

A brief article in the Chicago Tribune notes that Roth, along with George C[hadsey] Dorsey and Ernest [sic; sc. Emmet] M[alone] Manier “were passed for training as reserve officers in the aviation section of the signal corps” on May 31, 1917.7 All three went to the University of Illinois’s School of Military Aeronautics for ground school. Dorsey graduated July 28, 1917, and departed for England on August 18, 1917, on the Aurania as a member of what came to be called the first Oxford detachment.8 Manier and Roth graduated together on August 4, 1917, and Manier left, also on August 18, 1917, for France on the Baltic.9 Roth, however, remained stateside, and, unexpectedly, his name appears again on Illinois’s S.M.A. ground school graduation list for September 1, 1917.10 In the meantime, on August 19, 1917, his father, a recent widower, died; the death was apparently unexpected; concern about his father’s health thus does not seem to explain Roth’s delayed departure.11

In any case, men in the ground school classes of August 25 and September 1, 1917, were offered the opportunity of signing up to do their flying training in Italy (most had previously thought they would go to France), and Roth was evidently among those who chose this option. He proceeded to New York and on September 18, 1917, along with 149 other men who had signed up for Italy, boarded the Carmania at its pier in the Hudson River. Their first port of call was Halifax where the Carmania joined a convoy that set out on September 21, 1917, to cross the Atlantic. The men of the “Italian detachment” travelled first class and had plenty of leisure, apart from daily Italian lessons conducted by Fiorello La Guardia, who was travelling with them, and submarine watch duty towards the end of the voyage.

When the Carmania docked at Liverpool on October 2, 1917, the men learned to their initial consternation that they were not to go to Italy, but to remain in England and repeat ground school at the Royal Flying Corps’s No. 2 School of Military Aeronautics at Oxford University. They boarded a train that morning and arrived six hours later at the university, where they were assigned to rooms in various colleges. The next morning, Paul Stuart Winslow of the first Oxford detachment, which had arrived in England a month previously, noted in his diary that “The first person I saw this morning was the old man Jim Roth from Champaign – the solid old flyer – uneducated – but a wonderful flyer and a real man – never says anything except what he means, and it is always worth listening to.”12

It was initially thought that the men of what had just become the second Oxford detachment would remain at Oxford for six weeks, but it turned out to be four. On November 3, 1917, most of the men—but not Roth—were sent to a machine gunnery school, Harrowby Camp, near Grantham in Lincolnshire; this was a stopgap measure because there were too few openings at flying training squadrons. The next day Roth and fellow second Oxford detachment member William Ludwig Deetjen, still at Oxford, “walked out three miles to Wytham, an old, old village on the estate of Lord Abington. . . . We went in to the White Hart Inn for lunch. The land lord gave us the best meal we had since leaving ship board, and all for 4 shillings a piece. Real pie that came closer to an American apple than anything in England so far. Then we walked to the Port Meadow airdrome, where a fleet of eight planes had landed from the southern part of the country” and where they were able to see an Avro, and some Sopwith Pups and a Camel. “Jim and I walked over 8 miles & had supper at the Mitre Hotel.”13

The next day Roth, Deetjen, and eighteen other fortunate cadets set out for the R.F.C.’s No. 1 Training Depot Station at Stamford to begin flying.14 This group had been chosen by Elliott White Springs, the cadet in charge of the detachment. Springs selected mainly men who, like Roth, had already had flying experience—Roth probably more than any of the others.

Flying opportunities were at least initially less plentiful than the men had hoped due to inclement weather and a paucity of planes. Deetjen describes going out to the air field for the first time the day after their arrival at Stamford where they “managed to fool the whole morning away,” and learned that “our training planes, Curtiss JN4As had not arrived, and we could expect one or two most any day.”15 The afternoon was spent in yet more ground classes. On November 9, 1917, Deetjen got his first “joy ride” in a Curtiss Jenny16; Roth’s experience was perhaps similar. Meanwhile, in addition to the frustration of limited flying, living accommodations were a source of complaint. All the men were initially in a house with little heat and only cold water, and it was a relief when they were relocated to the Stamford workhouse—“over ½ mile out in the country in a gymnasium of the Work House. Fourteen of us in a large room and eight in smaller rooms.”17 Roth for a time shared a room with Raymond Watts and Deetjen; the latter describes now having “clean quarters & a fire is provided. The wash room is clean.”18

The amount of time the men spent flying and their progress at 1 T.D.S. varied. Neither Deetjen, who had not flown prior to Stamford, nor Arthur Richmond Taber, who had, were able to fly solo until sometime in December.19 Springs, on the other hand, went up solo a week after arriving at Stamford and had nearly twenty hours of solo flying by Thanksgiving.20 Given that Roth finished up his elementary training at Stamford early in the new year, his experience there was probably similar to Springs’s.

The only specific information on Roth’s flying there comes again from Deetjen’s diary. On January 3, 1918, Deetjen wrote that “Roth cracked [B]1949 so there are no more wheel busses left in our flight. Only two stick busses, namely [B]1942 & [B]1932.” (The “joy stick” control was by then in much wider use, but some of the JN4s at Stamford still used a wheel.)

Roth was evidently not injured in the mishap on January 3, 1918. Two days later, according to Springs he was “posted,” i.e. sent to a new training squadron.21 It is likely that this was No. 65 T.S. at Dover, where he is documented to have been at the end of March.22 No. 65 trained pilots to fly Camels, starting them on Avros and Pups; Roth’s R.A.F. service record notes his experience with these two planes.23 Roth apparently made good progress, as he was recommended for his commission sometime in February: Pershing’s cable with the recommendation is dated February 29, 1918, and the confirming cable from Washington March 9, 1918; Roth was placed on active service at Dover on March 31, 1918.24 (A month’s delay between the recommendation and active service as the paperwork moved from one desk to the next was fairly standard.)

Roth’s R.A.F. service record shows him still at No. 65 T.S. on April 3, 1918. A month later, on May 7, 1918, his medical board exam has him “Unfit G[eneral] S[ervice] 13 wks. Fit H[ome] S[ervice] Flying Duties”—i.e., he could fly, but not overseas. A medical card for him indicates that the reason for this was “defective vision.”24a It stipulates that he was “Not to fly until glasses have been obtained & never to fly without special goggles.”

Roth’s service record next records him at the R.A.F. Armaments School at Uxbridge on the western outskirts of London. He had “missed out” on the machine gun training that most other second Oxford detachment members had received at Grantham; however, the other cadets who went to Stamford instead of Grantham do not seem to have gone back for formal gunnery training, and it is likely that Roth’s assignment to Uxbridge involved preparing him for his final assignment, which was to Ford Junction on September 18, 1918.25

Ford Junction, on the south coast of England about halfway between Plymouth and Eastbourne, was a night bombardment training station. Early in 1918, the U.S. and Great Britain had agreed that the U.S. would manufacture the parts for over 300 Handley Page bombers and Liberty engines to be used by a planned thirty American night bombardment squadrons. The airplane parts were to be shipped to the U.K. for assembly by British workers and then used initially to train pilots and observers at several air fields allocated by Great Britain to the US Air Service in the so-called Chichester Area, including Ford Junction, which opened around the time Roth was assigned there. To say that the Handley Page program fell behind schedule is an understatement: at the time of the armistice, one Handley Page had arrived at Ford Junction in parts and was being assembled. Using instead a few American DH-4s, twelve British B.E.2e’s, and some pusher-type Farmans, the instructors and students at Ford Junction managed to get in just under a thousand hours of flying over the course of three months.26

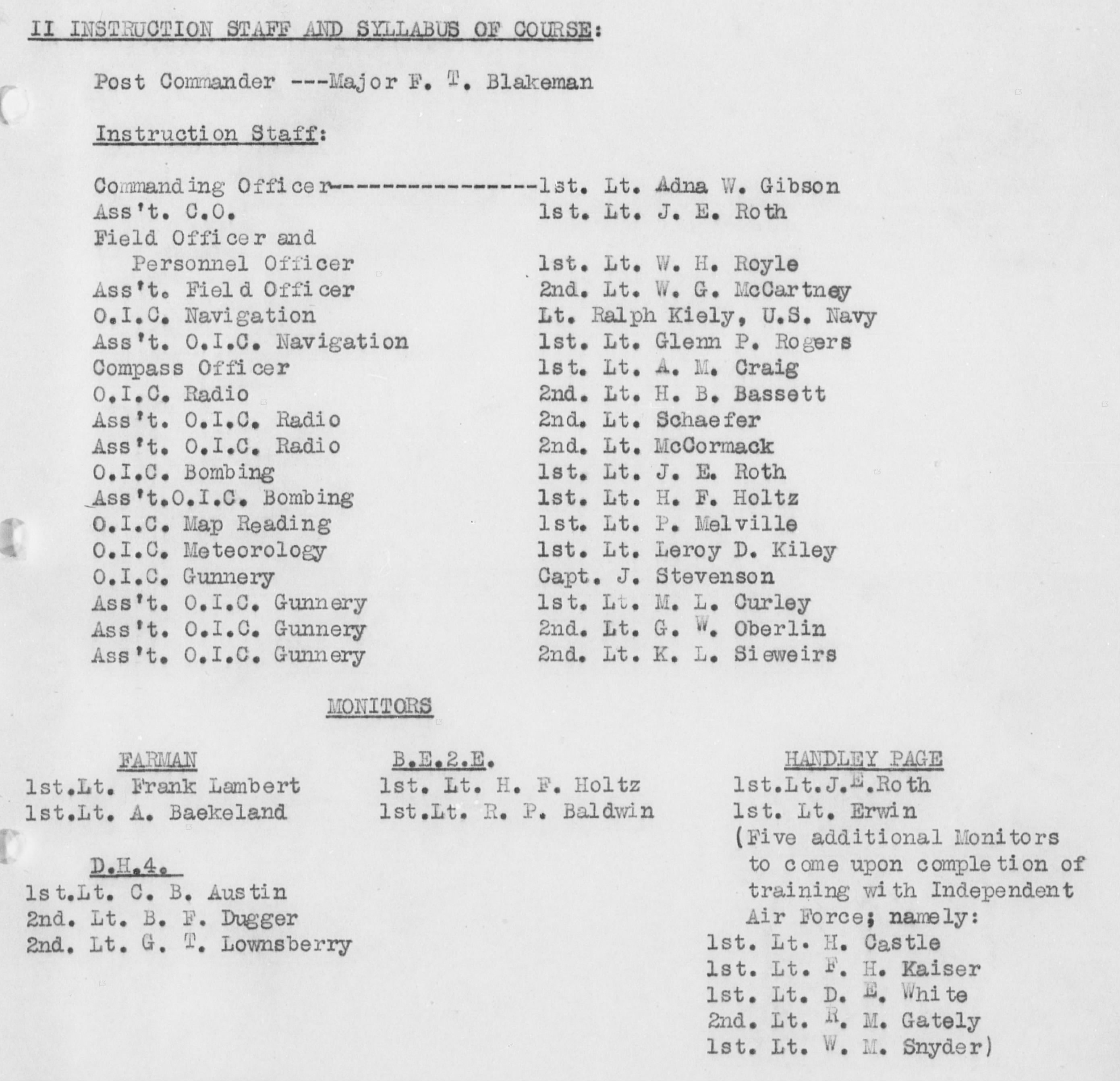

The commanding officer of the instruction staff at Ford Junction was Adna Wallace Gibson, and Roth was the assistant C.O.; he was also the officer in charge of bombing as well as being a monitor for Handley Page instruction—one of the few officers assigned multiple roles.27

On November 18, 1918, Roth and a number of his fellow officers were relieved of duty at Ford Junction and ordered to report to an American rest camp near Liverpool to await transport to the U.S.28 Other second Oxford detachment members returned home on transport provided by the military, but Roth apparently sailed as a private citizen. He had met and married an English girl, May Lousia Baines, and the couple sailed from Liverpool to the U.S. on the Megantic in December 1918.29

The couple settled in Pontiac, Illinois, not far from Benson, and Roth initially followed his father in going into the grocery business.3 At some point Roth returned to aviation, eventually becoming a private pilot for Chicago taxi company owner Walden W. Shaw.31

mrsmcq August 11, 2023; updated August 9, 2024, to reflect medical card

Notes

(For complete bibliographic entries, please consult the list of works and web pages cited.)

1 Roth’s place of birth is taken from Ancestry.com, U.S., World War I Draft Registration Cards, 1917–1918, record for James E Roth; the date is taken from Ancestry.com, U.S., Evangelical Lutheran Church in America Church Records, 1781-1969, record for Jacob Ernst Roth, which appears to be reliable. NB: Roth’s draft registration gives 1891 as his year of birth, as does a birth certificate document notarized in 1919 (document appended his wife’s passport application; see Ancestry.com, U.S. Passport Applications, 1795–1925, record for May L Roth). Birth year discrepancies are not uncommon among the men of the second Oxford detachment; these may have been related to military age limits, actual or rumored. Roth’ place and date of death are taken from “James E. Roth, War Flyer, Once I.W.U. Man, Found Dead.” NB: Ancestry.com, Illinois, U.S., Deaths and Stillbirths Index, 1916-1947, record for James E. Roth, gives his place of death as Northfield, Illinois. The photo, taken in 1925, was handed down in Roth’s family; I am grateful to his grandchildren and to Nancy Stafford for sharing it.

2 On Roth’s family, see documents available at Ancestry.com.

3 On his attendance at Illinois Wesleyan, see “James E. Roth, War Flyer, Once I.W.U. Man, Found Dead.” The name Roth appears in the context of sports in the Illinois Wesleyan yearbook and in the student newspaper during the relevant period, but I have not found an instance that includes his first name.

4 “Current Local Items.”

5 Gray, “Cicero Flying Field.”

6 See Roth’s draft registration, cited above.

7 “Three More Chicagoans to Train for Aviation Corps.”

8 “Ground School Graduations: Class of July 28.” There was confusion regarding the first Oxford detachment’s departure from New York, with their names included erroneously in the Philadelphia’s August 25, 1917, ship’s manifest. The outgoing manifest for the Aurania for August 18, 1917, is incomplete, but the detachment members’ names appear on the relevant arrival list. See Ancestry.com, U.S., Army Transport Service Arriving and Departing Passenger Lists, 1910-1939, [Outgoing], record for the Philadelphia; War Department, Office of the Quartermaster General, Army Transport Service, Lists of Outgoing Passengers, 1917 – 1938, record for the Aurania, sailing August 18, 1918; and Ancestry.com, UK, Incoming Passenger Lists, 1878–1960, record for Aurania arriving Liverpool, September 2, 1917.

9 Ancestry.com, U.S., Army Transport Service Arriving and Departing Passenger Lists, 1910-1939, [Outgoing], record for Emet [sic] M. Manier.

10 “Ground School Graduations [for September 1, 1917].”

11 “Jacob Roth Past [sic] Away Sunday Morning.”

12 Winslow, RFC/RAF No. 56 Squadron Diary of Paul Winslow.

13 Deetjen, diary entry for November 4, 1917.

14 Marvin Skelton provides a list of the men supposedly chosen by Springs for Stamford in his edition of Vaughn’s letters that does not include Roth (War Flying in France, p. 28), but the list is only partly accurate.

15 Deetjen, diary entry for November 7, 1917.

16 Deetjen, diary entry for November 9, 1917.

17 Deetjen, diary entry for November 13, 1917. This was probably the workhouse on Bourne Road; see Higginbotham, “Stamford, Lincolnshire.”

18 Deetjen, diary entry for November 19, 1917.

19 See Deetjen, diary entry for December 19, 1917, and Taber, Arthur Richmond Taber, p. 93.

20 See the transcriptions of his flying log on pp. 54–55 of Springs, Letters from a War Bird.

21 Springs’s diary entry for January 5, 1918, transcribed on p. 71 of Springs, Letters from a War Bird.

22 Biddle, “Special Orders No. 35.”

23 The National Archives (United Kingdom), Royal Air Force officers’ service records 1918–1919, record for James Ernest Roth.

24 Cablegrams 660-S, 900-R; Biddle, “Special Orders No. 35.”

24a I am grateful to the RAF Museum, London, for a scan of the card.

25 See his R.A.F. service record, cited above.

26 “Report on the Activities of the Mobilization and Training Department of the Night Bombardment Section, Air Service, American Expeditionary Force,” pp. 8–9 (22-23) and 20 (34).

27 “Report on the Activities of the Mobilization and Training Department of the Night Bombardment Section, Air Service, American Expeditionary Force,” p. 10 (24).

28 Biddle, Telegram.

29 Ancestry.com, New York, Passenger Lists, 1820–1957, records for James E Roth and for Mary [sic] Louisa Roth.

30 Ancestry.com, U.S. Passport Applications, 1795–1925, record for May L Roth (1923).

31 “James E. Roth, War Flyer, Once I.W.U. Man, Found Dead.”