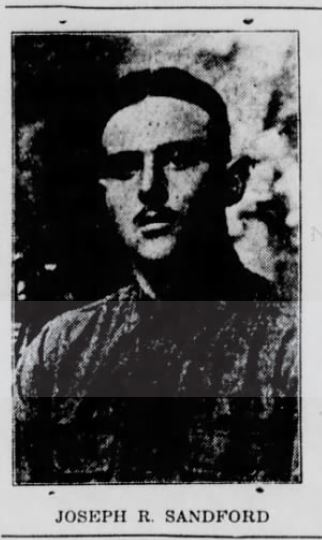

(Skowhegan, Maine, October 16, 1895 – near Wambrechies, France, April 12, 1918). 1

Oxford & Grantham ✯ Training in England ✯ France & 54 Squadron ✯ “Backs to the Wall” ✯ Afterwards

Sandford’s paternal grandfather, Joseph H. Sandford, was born in Canandaigua, New York, but grew up in Maine; I have not been able to trace his ancestry. He began farming at Skowhegan soon after his marriage to Mary S. White, a descendant of a John White from Somerset, England, who emigrated to Massachusetts around 1639. Mary S. White’s great-grandfather, John White (great-grandson of the earlier John White), moved to Canaan, Maine, just before the Revolutionary War; her parents resided in nearby Skowhegan and she was born there. Joseph Ralph Sandford’s father, Almon F., generally spelled his last name Sanford; he lived in Skowhegan where he farmed and was employed as a rural letter carrier. In 1893 he married Della Ames of Canaan; her Ames (Eames) family can be traced back to a Robert Eames who emigrated from England to Massachusetts in 1634. Joseph Ralph Sandford was the only child of Almon F. and Della Ames Sanford.2 His last name was often spelled “Sanford,” but Joseph Ralph was “Sandford” in most documents related to his military service, which accounts for his nickname, “Sandy.”

Sandford graduated from high school in Skowhegan in 1913 and enrolled initially at the University of Maine, but went on to attend Bowdoin College with the class of 1918; he was musical and played in both the orchestra and the band; a member of the biology club all three years at college, he also took part in student governance.3 In July of 1914 he joined the Maine National Guard as a member of Skowhegan’s Company E of the Second Maine Infantry Regiment.4 During the summer of 1916 the 2nd Maine was among the National Guard troops ordered to the Mexican border in connection with the Mexican Punitive Expedition. Stationed at Perron’s Ranch about forty miles up the Rio Grande from Laredo, Texas, from early July until mid-October 1916, the men were tasked with guarding fords of the Rio Grande.5 In what leisure time he had, Sandford collected rocks, plants, and insect specimens, which he brought back and donated to Bowdoin.6 The following spring, soon after the U.S. entered the European war, Sandford was among those in the Second Maine Infantry “selected to participate in the war maneuvers at the training camp at Plattsburg, N.Y.”7 He had perhaps already at this point decided to forgo or postpone his senior year at Bowdoin. From Plattsburg Sandford evidently applied for transfer to the Aviation Section of the Signal Corps. Once accepted, he attended ground school at M.I.T.’s School of Military Aeronautics; his class graduated August 25, 1917.8

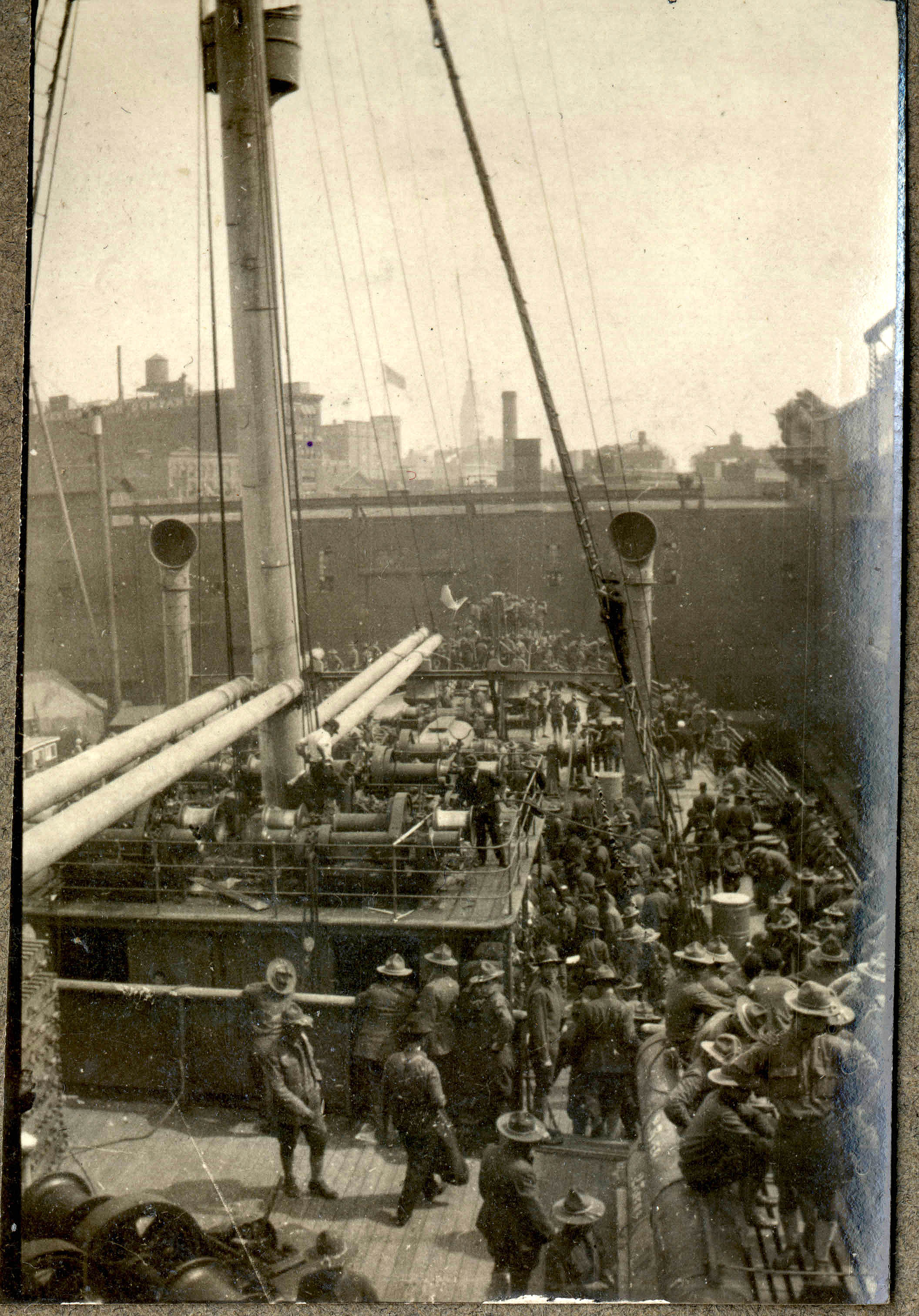

The second week of September 1917 finds Sandford at Fort Wood on Bedloe Island in New York Harbor, “one of the five honor graduates of his squadron who have been promised the best training in that line [aviation].”9 It is likely that Sandford, like Vincent Paul Oatis, also briefly at Fort Hood, was among those initially selected to train in France but then reassigned to Mineola where the detachment that was to go to Italy for its flying training was marking time.10 In any case, on September 18, 1917, Sandford and eleven others from his M.I.T. ground school class boarded the Carmania at a Cunard pier in the Hudson River as part of the 150-man strong “Italian detachment.” The ship sailed to Halifax and from there, on September 21, 1917, set out as part of a convoy to cross the Atlantic. The men of the detachment travelled first class and had plenty of leisure, apart from Italian lessons given by Fiorello La Guardia, who was travelling with them, and, once they entered dangerous coastal waters, submarine watch duty.

Oxford & Grantham

When the Carmania docked at Liverpool on October 2, 1917, the men were greeted with the news that they would not go to Italy but remain in England and, even worse, as it seemed, go through ground school all over again. They made the six-hour rail journey to Oxford and Oxford University where the Royal Flying Corps’s No. 2 School of Military Aeronautics was located, and the “Italian detachment” became the “second Oxford detachment”—a first detachment of fifty American pilots in training having arrived there a month earlier.

The men settled into rooms in Christ Church College and The Queen’s College. Classes to a large extent covered material they had already studied, but having instructors who had had flying experience at the front made it more interesting. The American cadets did not have to work especially hard and found time to enjoy Oxford hospitality and to explore the town and the surrounding countryside on foot, by bike, and by boat. Two weeks into their time at Oxford there was a considerable upheaval: the men of the first Oxford detachment staged a bibulous celebration of the end of their course, with some men of the second joining in. Sandford was not among the revellers, having dined more decorously at Buol’s with men he knew from M.I.T. ground school: William Ludwig Deetjen, Conrad Henry Matthiessen, and Phillips Merrill Payson.11 But the British authorities were annoyed at the unruly Americans and insisted that they all be reassigned to a single college, Exeter, and there they remained until early November.

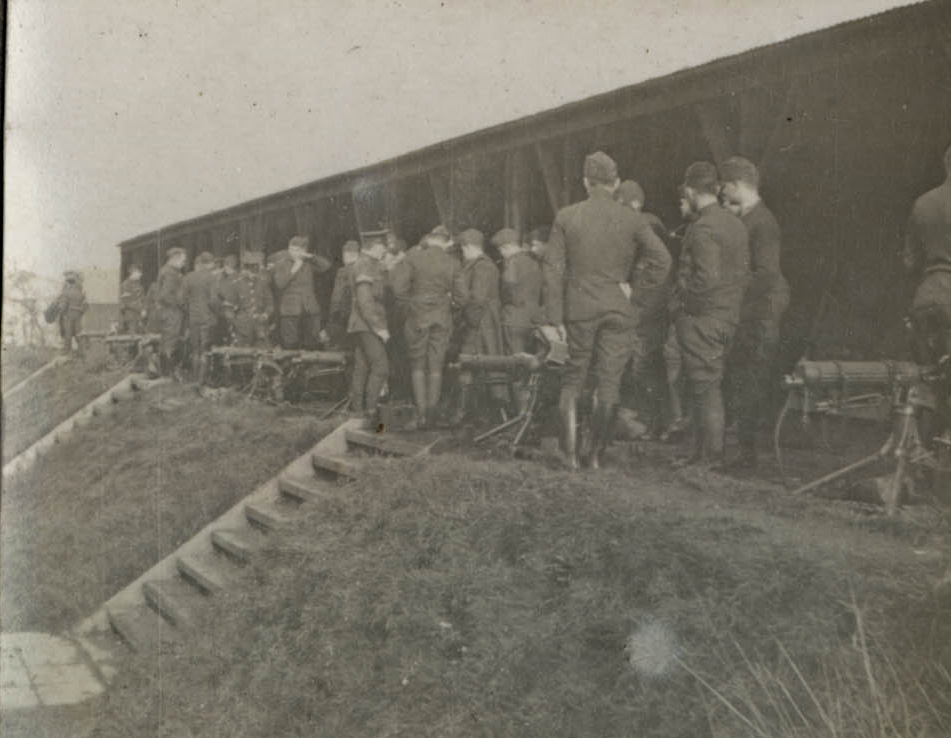

The men were eager to start flying training, but more disappointment was in store for most of them. The R.F.C. was able to accommodate twenty men from the detachment (including Deetjen) at No. 1 Training Depot Station at Stamford, but the others were sent to a machine gunnery camp near Grantham in Lincolnshire. Deetjen wrote in his diary on November 4, 1917: “Yesterday it was rather hard to see 129 of our outfit leave for Grantham Gunnery School. They left at 9 A.M. with Fred Stillman in charge. Pat Payson, Matty, & Sandy all went.”12

The course at Grantham was to involve two weeks on the Vickers gun, and then two on the Lewis. Shortly before the end of the Vickers course, as Joseph Kirkbride Milnor noted in his diary, “There was a rumor afoot that 50 of us were to be posted on Monday [November 19, 1917] to flying Squadrons. Much excitement about it.”13 The next day “The rumor of posting was confirmed. . . . Five of us are going to Tadcaster somewhere up in Yorkshire.”14 The five selected for Tadcaster, seventy miles north of Grantham, were Milnor, Sandford, Henry Bradley Frost, Lloyd Andrews Hamilton, and Hugh Douglas Stier.

Training in England

Once arrived at Tadcaster and No. 14 Training Squadron on November 19, 1917, Sandford, along with Frost and Hamilton, was assigned to A flight under Australian Harry Turner Shaw, and Milnor and Stier to C flight under George Robert Graham Smeddle.15 The planes used for instruction were Maurice Farman S.11s, known as “Rumpties.” These were two-seater “pusher” planes, i.e., ones with the propeller behind the cockpit. They had been used at the front early in the war but were now, fitted with dual controls, used for training. Another second Oxford detachment member, Parr Hooper, wrote that the M.F. S11 was “excellent to learn on because it has no inherent stability and must be flown (meaning controlled) all the time,”16 and Milnor similarly remarked that the M.F. S11s “are rather difficult to fly but are said to give great confidence when left behind and we go on regular machines.”17 Milnor also noted that “The wind here is pretty bad. We are in the worst part of England and at the worst time of the year for flying weather.” Nevertheless, Milnor was able to make his first twenty-minute flight with his instructor on November 22, 1917; Sandford had to wait until November 26, 1917. On that day,

I got up at 7.30 and had a little breakfast and then went down to the aerodrome. . . . I got down there and my instructor came up soon after and said ‘Oh you haven’t been up at all have you?’ I said ‘no’ so he jerked his head and told me to come along. . . . After the engine was warmed up he told me to hold the controls lightly so as to see what he did and said he would take his hands off a while and let me run it. . . . After a little run we left the ground and began to go up slowly. I didn’t have any sensation at all. You know I get dizzy when I look down from a building, but I didn’t feel it at all when I looked down at the ground. We went up somewhere about 1500 feet and then sailed around. When we had made about one-half a turn around the field, he held his arms out and left me with the darned thing. I just had to go thru with it so I kept her straight and let her go. Once in a while we would strike a bump and go up 20 or 30 feet and next drop about the same. Sometimes one wing would go down, then the other but you wouldn’t notice it, I mean in any way to be scared. A little move will tip her up or down or roll her on either side. Well we went around a couple times and then he motioned me to put her nose down a bit. When I had he cut the engine down and we glided. It is great sport. Of course when we came pretty near the ground he took her and we landed.18

They went up twice more, with Sandford learning to bank and the instructor demonstrating simple maneuvers. “I got in 35 minutes in all and it counted as dual. Mind you, the first time I had ever been up. The whole thing was great.”19

Sometimes a student’s first flight was just a “joy ride,” but Sandford was glad that his first time in the air “counted as dual” towards the required training hours. Milnor noted that “We will have to do between 4 and 6, possibly more, hours dual control and 2 hours solo with ten landings, when we will then go to an advanced Squadron.”20

Sandford had written home about his first flight on Wednesday; the next day was Thanksgiving, which was celebrated in great style by the men still at Grantham. Deetjen took the train from Stamford to Grantham so he could join in, evidently hoping Sandford would also be there: “Matty came from Northolt, but Sandy never arrived.”21 Sandford had gone instead with the other men at Tadcaster to Leeds for Thanksgiving dinner: “The five of us and Johnston, a Canadian, . . . had a regular dinner in a private dining room at the Queens, oysters, turkey, etc. and then went to a Vaudeville show . . . a very enjoyable evening, considering we were so far away from home.”22

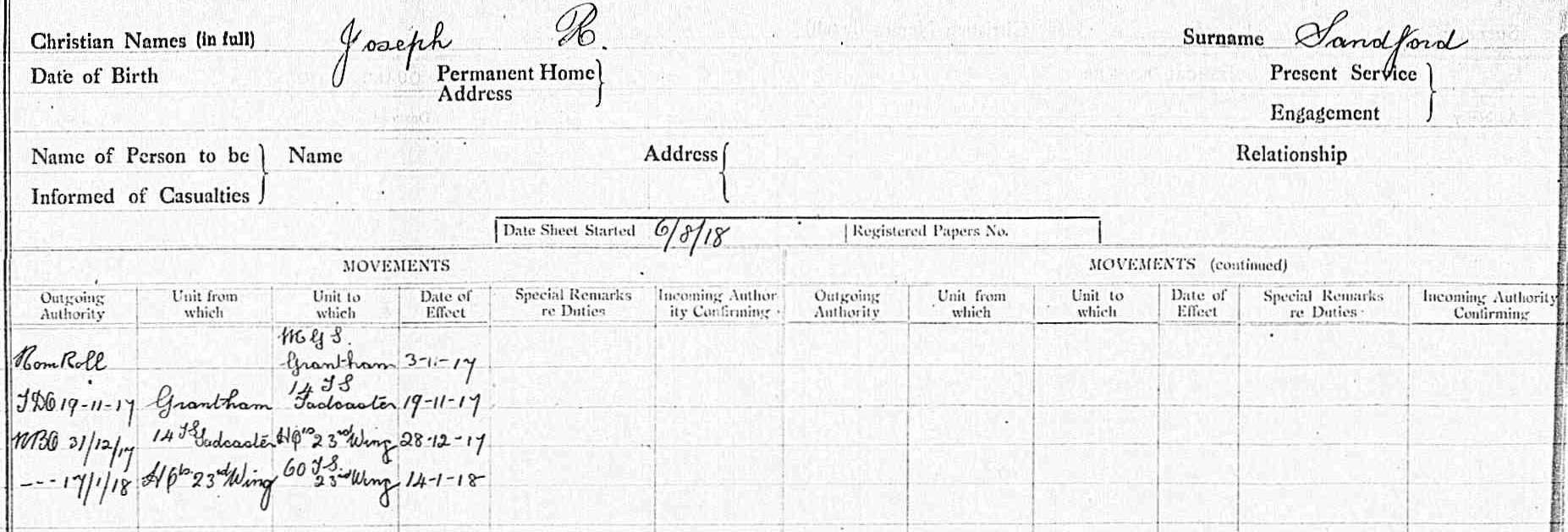

The “Big Five at Tad” were split up shortly before Christmas, with Hamilton, Milnor, and Stier sent to “the 23rd Wing, South Carlton just north of Lincoln for disposal” on December 20, 1917.23 According to Milnor, they were posted to No. 45 T.S. there, and spent the rest of the month taking ground classes, awaiting further assignment. Sandford was posted to 23rd Wing eight days later, on December 28, 1917, and he presumably also did ground work until, on January 14, 1918, he was posted to No. 60 T.S. at Scampton just north of South Carlton.24

There he probably trained initially on Avros before moving on to Spads and Pups. The weather must have been better than it had been during his time at Tadcaster, as he was able to make rapid progress. His R.A.F. service record notes: “American Cadet Grad. C.F.S. 30-1-18,” meaning that by the end of January 1918 he had passed a number of significant tests and was now qualified as a flying officer.25 He had also done enough flying to be eligible for his commission, and the recommendation was passed on to the American authorities. Pershing’s cable with Sandford’s name among a number of men recommended for their commissions is dated February 16, 1918, and the confirming cable coming back from Washington is dated March 1, 1918.26

In the meantime, Sandford was already flying Camels with confidence. Deetjen, now at Waddington, just south of Lincoln, wrote in his diary on February 17, 1918, that “When I got home Sandy was there, having come in a Camel from Scampton. Next week he goes to Turnberry for his gunnery.”

I have not found the date for Sandford’s posting to the No. 2 School of Aerial Gunnery at Turnberry on the west coast of Scotland, nor the date for his posting to the No. 1 School of Aerial Fighting at Ayr just to the north. However, it is clear that he was at Ayr on March 12, 1918, when Murton Campbell wrote in his diary that he and Sandford “had begun flying this afternoon”; Campbell was back on Avros for a time, and the same was presumably the case for Sandford. Two days later, on March 14, 1918, Campbell wrote that “I went up this morning with Capt. [Geoffrey Arthur Henzell] Pidcock on dual fighting. . . . When I came down at 11:30 from a Camel flip the Capt. informed Sandy and I that we were going overseas. . . . Zip, Whiting, Ham, and Kissel were the other four to go on the same journey. We left for London on the 8:45.”

(The four were Errol Henry Zistel and George Clarke Whiting of the first Oxford detachment, Hamilton of the second, and Gustav Hermann Kissel, who had graduated from M.I.T. ground school on July 14, 1917, and done some training in France before being sent to Ayr to finish up.)

Campbell records the events of the next day, March 15, 1918:

Arrived in London about 8:30 after a rather cool and tiresome journey. We first took our baggage to Vic[toria] Station, ate breakfast, and went to Aviation Headquarters where we hung around until one o’clock. After lunch we visited American Hdqrs. for instructions and returned to R.F.C. again. Major General Longcroft27 gave us a talk, on account of our being the first Americans attached to R.F.C. to go overseas. . . . Sandy, Whiting, Ham and I were sent out about 15 miles to take a gas course.

Campbell describes how the next day, Saturday, March 16, 1918, the four men set out from Charing Cross for Folkstone and there embarked for Boulogne: “The trip was about two hours in length and a breezy one, altho’ the Channel was not rough. At Boulogne we separated our luggage and checked it at the Central Station. At the R[ailway] T[ransport] O[fficer]’s office we got our orders. Sandy, Ham and Whiting were posted direct to squadrons and I to the pool at Candas. The four of us had a good dinner at some hotel and then separated about 11:30 as I had to go to my train.”

France & 54 Squadron

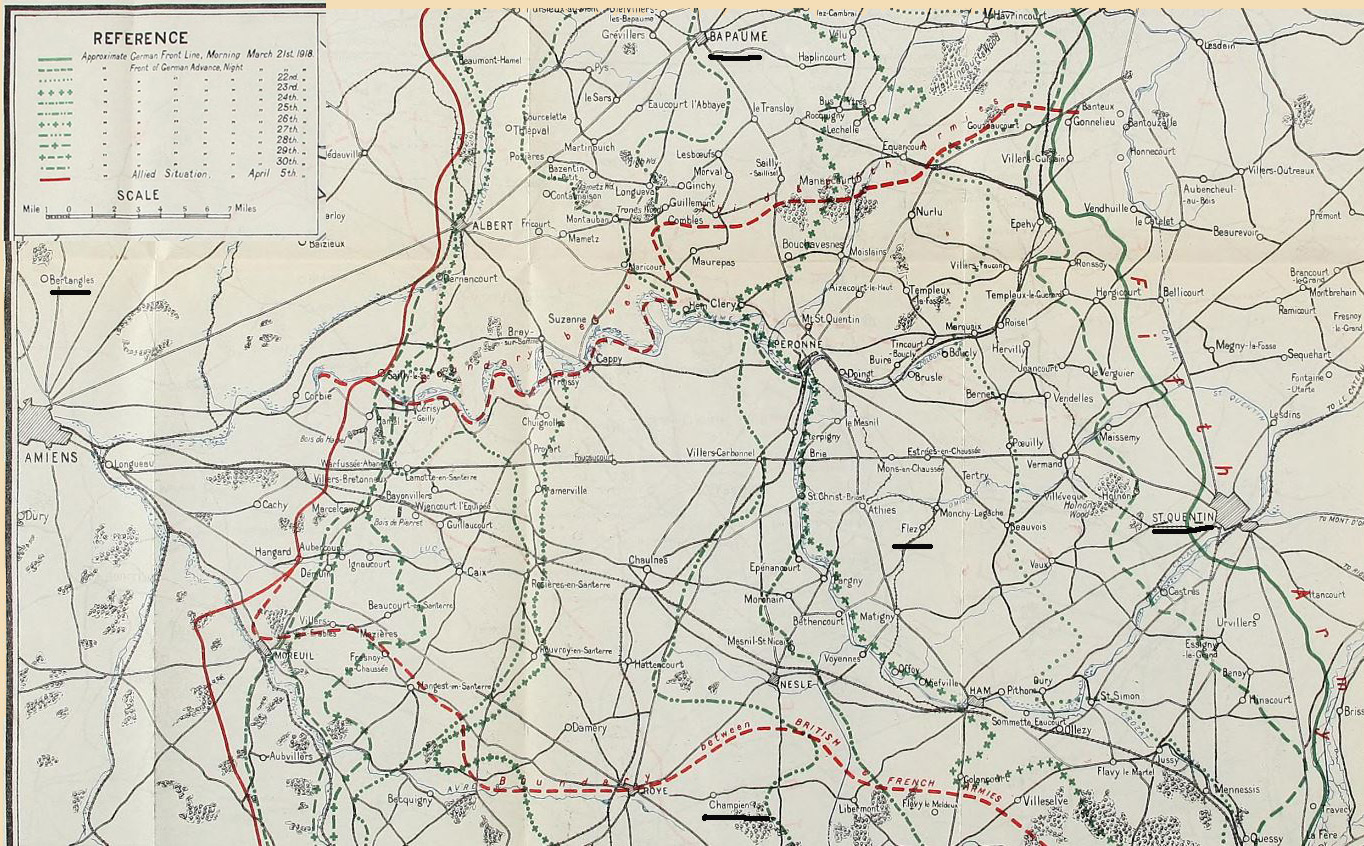

Hamilton had been posted to No. 3 Squadron R.A.F., Whiting to No. 43, and Sandford to No. 54—all Camel squadrons. No. 54 Squadron was at this time at Flez aerodrome near Guizancourt, about twelve miles west of St. Quentin. It was part of the 22nd (Army) Wing, attached to V Brigade, which supported the Fifth Army, whose front at this date was centered just west of German-occupied Saint Quentin. Campbell arrived at 54 three days after Sandford: “I was pleased to have been posted here on account of Sandy being here.” “Our drome is only about 8 or 9 miles behind the lines so that the flashes and boom of the big guns are quite plain. Only a short distance from here there is a battery of 15″ guns. When they get started there will be something doing. They have been expecting a big Hun push on this part of the lines for about a fortnight, but it has not come off as yet.”28

The “big Hun push,” the Germans’ spring offensive, commenced on March 21, 1918. Campbell wrote in his diary that day that “Guns started to boom last night about 11 o’clock and went full blast all night. . . . Preparations were made for moving the drome so everyone took it upon themselves to pack their kits.” Meanwhile, however, “The squadron pulled off about 4 shows over the lines, nobody being hurt at all”; Sandford and Campbell were too new to the front and the squadron to be called on to participate. (I should note that the No. 54 Squadron record book for this period appears not to be extant, so that my reconstruction of events relies on other sources and on educated assumptions.)

On March 22, 1918, the squadron moved to Champien: “More wind up this A.M. as the Hun pushed in a few miles further, being only 5 or 6 miles away. Everything but machines were packed and sent away on lorries so that the intrepid aviators are about the only things left around here. . . . The Hun was only 3 ½ miles away when we departed at 3:30 from Guizancourt. Everyone took a bus [airplane] and went S.W. for Champien. It did not take long to fly over there.”29 At Champien Sandford and Campbell crossed paths briefly with Minneapolis-born George Helliwell Harding, whom they had known at Scampton and who was now flying Sopwith Dolphins with No. 79 Squadron.30

Two days later, as the Germans continued to push west, No. 54 Squadron moved again: “We were detailed to the Bertangles drome, which is about 5 miles north of Amiens. . . . The transports were miles away at dinner time, so Sandy, [Thomas Sydney Curzon] Howe, [Ernest James] Salter, and I went into Bertangles for a feed. We got five eggs apiece to start in on and in the meantime Sandy and Howe talked French to the little maidens. We slept in a little house having a brick floor and a wooden roof which was a fair rival to Bobby Burns’s cottage.”31 Flying out of Bertangles on March 26, 1918, No. 54 briefly assisted on the Third Army front to the north as the Germans massed troops west of now captured Bapaume, before returning south to join in attacks on ground targets on the Fifth Army front.32 Campbell remarked that “Nearly every show the men had on, they returned with bullet holes thru’ their machines and a good many of them rather close to be very healthy.”33

The next day, “orders were received . . . to evacuate this drome for another.” So, on March 28, 1918, “At 5 o’clock about a dozen Camels left for our new joint at Conteville,” about twenty miles north-northwest of Bertangles. Rain and no mess at the new site made for a gloomy arrival. “Our quarters [are] composed of about a dozen army tents. Sandy, Howe, and I selected one and set up our cots. For dinner we had a tin of bully beef and some biscuits plus a fairly good soft drink.”34 Bad weather meant that there was only one patrol over the lines the next day. On March 31, 1918, No. 54 was among the squadrons attacking “troops along the Amiens-Roye road particularly, and south of the Somme generally.”35

On April 1, 1918—the day that the Royal Flying Corps. became the Royal Air Force—Sandford and Campbell “took a little trip into Abbeville” about twelve miles west-southwest of Conteville, “the main idea being to take a bath and we got it too. After purchasing a few necessities we returned to camp feeling a whole lot better.”36

A few days later, a rumor circulated that “the whole squadron was going on three weeks leave”; the next day, according to Campbell, the rumor was confirmed.37 On April 7, 1918, the squadron flew approximately forty miles north to St. Omer and settled into new quarters at Clairmarais-Sud, just northeast of St. Omer: “Our quarters are very good and I expect we will enjoy our stay at this airdrome.”38

I cannot tell whether the relocation to Clairmarais really was intended to initiate a rest period, or whether it was a tactical move in anticipation of the Germans’ next offensive. In any case, No. 54 Squadron was around this time transferred to II Brigade, which supported the Second Army, centered on Ypres.39 Having failed to capture Amiens, the Germans ended the first phase of their spring offensive on April 5, 1918. They now turned their attention to the north, and on April 9, 1918, the Battle of the Lys commenced in Flanders, with the German 6th Army advancing on Armentières. Campbell wrote in his diary the next day that “The Huns started a big bombardment last night and had the nerve to advance about 5 miles on a 10 mile front just south of Armentiers [sic]. It seems that this squadron runs right into trouble all the time. All pilots had to ‘stand by’ at dawn this morning but there was a mist on which prevented any patrols from going out.” In the afternoon, Sandford, Campbell, and Howe went into St. Omer but “returned for dinner. We had no more than started dinner when the anteroom caught on fire. It went up in smoke together with the gramophone and piano. Just a little excitement to keep things going.”40

“Backs to the Wall”

It appears that Sandford took part in his first offensive patrol the next day, April 11, 1918. Campbell wrote in his diary that day that “This afternoon I was on the second patrol but my engine choked on taking off so did not go. Sandy went, however, and did not complain a great deal about it.”

With the British rail center of Hazebrouck and the Channel ports in danger, the situation in Flanders was extremely grave for the Allies, so grave that on April 11, 1918, Haig wrote a “Special Order of the Day” with the uncharacteristically eloquent and inspirational passage: “There is no other course open to us but to fight it out. Every position must be held to the last man: there must be no retirement. With our backs to the wall and believing in the justice of our cause each one of us must fight on to the end. The safety of our homes and the Freedom of mankind alike depend upon the conduct of each one of us at this critical moment.”41

It was generally understood that pilots new to the front and an operational squadron needed time, usually two to three weeks, to become familiar with the planes, the territory, and their duties. The experience of Theodore Rickey Hostetter, a Harvard man from Pittsburgh, shows that no such allowances were possible at this time. Posted to 54 on April 5, he participated in his first (and last) offensive patrol with 54 on April 11, less than a week after his arrival.42

The next morning, April 12, 1918, at 7:50, Campbell and Sandford took off as part of an offensive patrol, the latter flying Camel B5424.43 In his diary for that day Campbell described his first time over the lines and first experience of German anti-aircraft artillery (archie):

Went on a high offensive patrol at 8–10,000 feet. We got archied like hell. The first I noticed was a big barrage directly in front of us, something like a formation of about 50 machines. Then they burst all around us so that we had to beat it out of the neighborhood. We were separated. I for one going my own direction, followed by two other machines. Only nine got back over Foret Nieppe. Sandy was missing so all I can see is that he was brought down by Archie or else got lost in Hunland or France.

Campbell arrived back from his third patrol that day “just after sunset. [Ian] McNair was also missing, and nothing had been heard of either he or Sandy. Am a little put out about Sandy on account of being with him so long and forming such a good friendship. I have hopes, however, that he will turn up like many others have done in the past.” This is Campbell’s last mention of Sandford in his diary, in which, on subsequent days, he tries to keep track of all the men from the squadron wounded, missing, or killed.

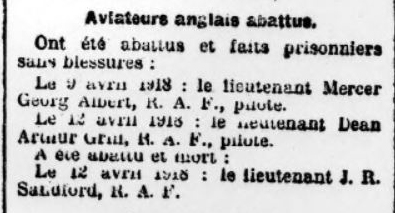

The casualty report for Sandford and Camel B5424 states that he was “Last seen under control E of Armentières diving on EA on offensive patrol.”44 Hans-Georg von der Marwitz of Jagdstaffel (fighter squadron) 30 was credited with shooting down a Camel near Wambrechies at 8:30 the morning of April 12, 1918, and it is assumed that the Camel was Sandford’s.45

Afterwards

By April 17, 1918, word had gotten back to Milnor in London that “Sandy and Kissell are missing,” and the news about Sandford reached Deetjen at Marske-by-the-Sea on April 21, 1918.46 On May 11, 1918, in Skowhegan, Sandford’s father received the information that his son was missing.47

A telegram on May 15, 1918, brought the worst news: “the Red Cross . . . has received cable from the Red Cross in France that the Gazette Des Ardennes, a semi-official German newspaper, which circulates to some extent in France, contains the statement that Joseph R. Sanford aviator, previously reported missing April 12th, is now reported as having been killed.”48 Sandford was the first man of either of the two Oxford detachment to be killed in action.

After the war, in May 1919, Sandford’s father received further news in the form of a memo from Frederick W. Zinn, an aviator who had been tasked with locating the graves of missing American airmen. Zinn reported that, after failing to find information on Sandford at the German Central Records Office and in lists on file at German Aviation Headquarters, he contacted the Central Effects Depot in Berlin, whose reply he offered in translation:

The Aviator Lieut. J. R. Sanford (Sandford) Pilot R.A.F. according to report of the Intelligence Officer of the O.H.L. [Supreme Army Command] with the A.O.K. 6 [6th Army] of April 26th 1918 . . . was killed, his machine having crashed after a combat near Wambrechies, and was buried in military cemetery La Justice near Quesnoy in grave No. 949. His effects . . . was [sic] turned over on Sept. 6th, 1918 with the English Effects . . . to the Netherland [sic] Legation.

Wambrechies was about seven miles due east of Armentières; Quesnoy-sur-Deûle about six miles east-northeast. Zinn went on to say that “The information reference his [sic] grave location has been forwarded by wire to Captain J. F. Thompkins, American Graves Registration, Area No. 3, Amiens, with a request that he locate and mark your son’s grave, which I am sure he will endeavor to do.”49

After the war relatives of American military personnel who had died in Europe were consulted about the final disposition of the bodies of the deceased. Sandford’s parents chose to have their son’s body returned to them. In the autumn of 1921 it was disinterred from the cemetery near Quesnoy and taken to Antwerp for transport to the U.S., along with nearly 2500 other bodies, on the U.S.A.T. Wheaton.50 A funeral was held in Skowhegan, where Sandford was reburied on October 9, 1921.51

mrsmcq July 22, 2023

Notes

(For complete bibliographic entries, please consult the list of works and web pages cited.)

1 Sandford’s place and date of birth are taken from Maine, Adjutant General. Roster of Maine, vol. 2, p. 309. His place and date of death are taken from Ancestry.com, Maine, U.S., Veterans Cemetery Records, 1676-1918, record for Joseph Ralph Sandford. The photo is taken from p. 81 of The Bowdoin Bugle 1918.

2 Information on Sandford’s family is taken from documents available at Ancestry.com and from Ames, Eames-Ames Genealogy and from White, Genealogy of the descendants of John White.

3 “Skowhegan”; Bowdoin College, Addresses, p. 29; Bowdoin Bugle 1918, p. 81.

4 Maine, Adjutant General, Roster of Maine, vol. 2, p. 309.

5 “Sandford ’18 Returns from Texas” (where the location is given as “Peron’s Ranch”).

6 “Bowdoin Aviator Buried at Skowhegan.”

7 “National Guard Men Who Go to Plattsburg, N.Y.”

8 “Ground School Graduations [for September 1, 1917].”

9 “Skowhegan News.”

10 At least three of Sandford’s M.I.T. ground school classmates (Roger Whittaker Rowland, Edmund Arthur Donnan, and Talbot Otis Freeman) were in the detachment that departed New York on September 25, 1917, on the Saxonia, “destined for France,” as the ship’s manifest describes them, although Donnan and, initially Freeman, were sent to Italy instead. See Ancestry.com, U.S., Army Transport Service Arriving and Departing Passenger Lists, 1910-1939, pp. 82 et seq. On Donnan and Freeman, see the entries for them in Mead, Harvard’s Military Record in the World War; on Freeman, see

11 Deetjen, diary entry for October 21, 1917.

12 For those doing the arithmetic: one man, James Whitworth Stokes, remained in Oxford due to illness.

13 Milnor, diary entry for November 14, 1917.

14 Milnor, diary entry for November 15, 1917.

15 On the flight assignments and flight leaders, see Milnor, diary entry for November 20, 1917.

16 Hooper, Somewhere in France, letter of November 23, 1917.

17 Milnor, diary entry for November 20, 1917.

18 This is from a letter dated November 28, 1917, that Sandford wrote to his parents from Tadcaster published in a newspaper in Skowhegan; see “Joseph R. Sanford Writes of Sensations Felt during his First Flight.”

19 Ibid.

20 Milnor, diary entry for November 20, 1917.

21 Deetjen, diary entry for November 30, 1917.

22 Milnor, diary entry for November 29, 1917.

23 Milnor, diary entries for December 19, 1917, et seq.

24 The National Archives (United Kingdom), Royal Air Force officers’ service records 1918–1919, record for Joseph R. Sandford.

25 C.F.S. is Central Flying School, responsible for setting military aviation requirements.

26 Cablegrams 612-S and 852-R.

27 Charles Alexander Holcombe Longcroft was at this time overseeing the R.F.C.’s training division.

28 Murton Campbell, diary entry for March 19, 1918.

29 Murton Campbell, diary entry for March 22, 1918. There is a detailed map showing the German advance after p. 266 of Jones’s The War in the Air, vol. 4. Flez was in German hands at the end of the day on March 23, 1918.

30 Murton Campbell, diary entry for March 22, 1918.

31 Murton Campbell, diary entry for March 23, 1918.

32 Jones, The War in the Air, vol. 4, pp. 323–24; 326.

33 Murton Campbell, diary entry for March 26, 1918.

34 Murton Campbell, diary entry for March 28, 1918.

35 Jones, The War in the Air, vol. 4, p. 342.

36 Murton Campbell, diary entry for April 1, 1918.

37 Murton Campbell, diary entries for April 5 and 6, 1918.

38 Murton Campbell, diary entry for April 7, 1918.

39 On the assignment to II Brigade, see Jones, The War in the Air, vol. 4, pp. 377–78. I assume it was assigned to the 11th (Army) Wing, but cannot document this with certainty. Sturtivant, Hamlin, and Halley, Royal Air Force Training and Support Units, pp. 311 and 313, list No. 54 with both No. 11 and No. 22 Wing during April, May, and June 1918.

40 Murton Campbell, diary entry for April 19, 1918.

41 Sheffield, Douglas Haig: From the Somme to Victory, Chapter 9; see “Backs to the Wall” for a digital image of the original order.

42 See “Hostetter, T.R.” and “2nd Lieut., Lieut.Theodor Rickey Hostetter”

43 The departure time is provided both by Henshaw, The Sky Their Battlefield II, and Sturtivant and Page, The Camel File.

44 The report at the National Archives (UK), Air 1/854, is cited by Pentland at his Royal Flying Corp web site. The relevant casualty card, “Sandford, J.R. (Joseph R.),” mistakenly puts him west of Armentières

45 Franks, Bailey, and Duiven, The Jasta War Chronology, pp. 159–60 where, for “B524,” read “B5424.

46 See their diaries for these dates.

47 “‘Joe’ Sandford Missing.”

48 “Skowhegan Boy Aviator Believed to have Lost Life.” The telegram appears to have been sent from Washington, D.C., by Maine Congressman John Andrew Peters.

49 Zinn, Memo dated May 14, 1919, to Mr. Almon F. Sanford. The text of the reply from the Central Effects Depot is also reproduced in “Final Report Concerning the Death of Lieut. Joseph R. Sandford.”

50 Sandford, Joseph R.”; War Department, Office of the Quartermaster General, Army Transport Service, Lists of Incoming Passengers, 1917 – 1938, Military Deceased.

51 “Joseph R. Sandford’s Body Rests.”