(Milwaukee, April 5, 1898 – Milwaukee, December 4, 1961).1

Carpenter was from a prominent Milwaukee family. His paternal grandfather had been a U.S. senator from Wisconsin and could trace his family back to Carpenters who emigrated from England to New England on the Bevis in 1638.2 Carpenter’s mother was Emma Falk, whose father emigrated in 1848 from Bavaria and founded a major Milwaukee brewery.3

Carpenter for two years attended Marquette Academy, the high school associated with Marquette University in Milwaukee, before transferring to the Newman School, a private Catholic prep school in Hackensack, New Jersey, from which he graduated in 1917.4 He was too young to register for the draft but nonetheless entered service on July 5, 1917, at Princeton, New Jersey.5 He was a good friend of New Jersey-born Edward Matthew Cronin (also Catholic and also with family connections to the brewing industry), and they were students together at the Princeton School of Military Aeronautics.6 Both appear in photos of the first graduating class, although not on public lists of graduates.

Like the majority of men in that ground school class, Carpenter chose or was chosen for flight training in Italy, and he joined the 150 men of the “Italian” or “second Oxford detachment” who sailed to England on the Carmania. They departed New York for Halifax on September 18, 1917, and departed Halifax as part of a convoy for the Atlantic crossing on September 21, 1917. Around September 27, 1917, the convoy entered the danger zone, and the men of the detachment were detailed for “submarine watch”; Carpenter shared shifts with Murton Llewellyn Campbell.7

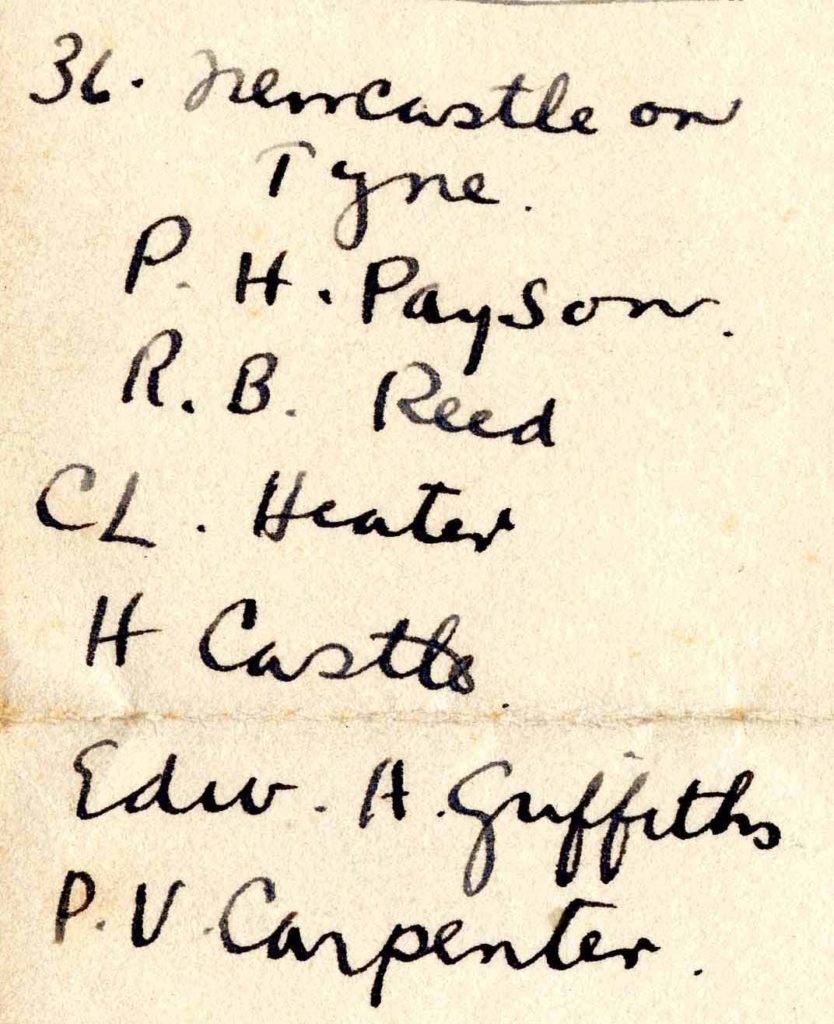

When the Carmania docked at Liverpool on October 2, 1917, the detachment learned to their initial consternation that they were not to go to Italy, but to remain in England and repeat ground school at the Royal Flying Corps’s No. 2 School of Military Aeronautics at Oxford University. In early November, places at Stamford became available for flight training, and several of those who had been at Princeton were selected to go there. However, Carpenter, as well as Edmond Thomas Keenan, Walter Burnside Knox, and John Howard Raftery from Princeton ground school, were not among the lucky twenty. Instead they were part of a large group who set out on November 3, 1917, for Harrowby Camp, a machine gun school near Grantham in Lincolnshire.7a Fifty of the men at Grantham were able to leave after two weeks for flying schools, but Carpenter was among those remained there through Thanksgiving and the end of November. Finally, on December 3, 1917, according to a list drawn up by Fremont Cutler Foss, Carpenter was one of the six men posted to No. 36 Squadron, a home defense squadron flying F.E.2d’s based in and around Newcastle.8

A brief mention of Carpenter on February 8, 1918, in the diary of his fellow detachment member Foss suggests that by early February Carpenter was with Foss at a training squadron at Waddington in Lincolnshire. The diary entry of another cadet, William Ludwig Deetjen, places Carpenter at Waddington at the end of March: “In the afternoon my spurs came, and I matched Carpenter of Milwaukee to see if he should get his free or pay double. He won.”9

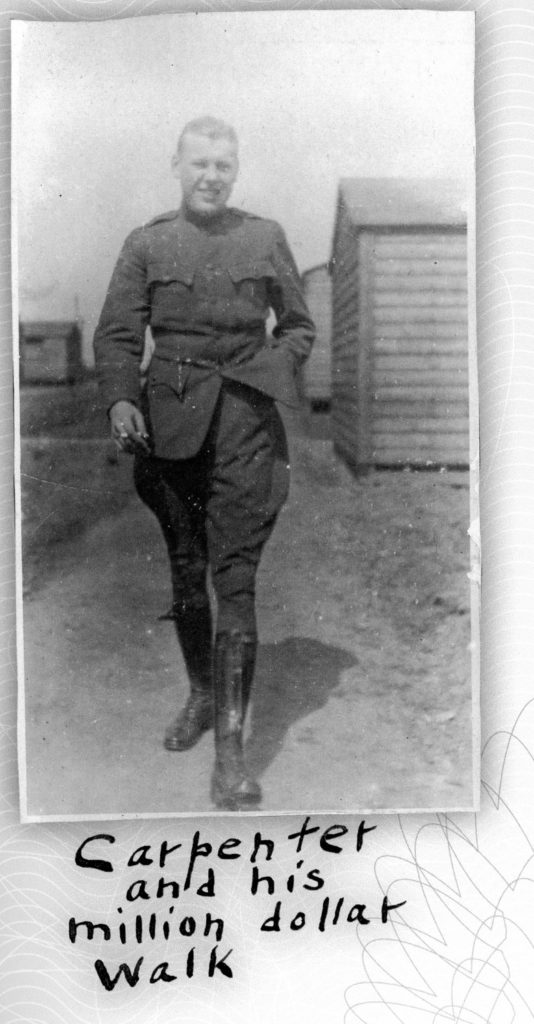

There is an engaging photo of Carpenter in uniform striding towards the camera probably taken at Waddington by fellow detachment member Joseph Raymond Payden. In a document from 1919, Carpenter notes that he received his commission as a first lieutenant at Waddington on May 16, 1918. The same document indicates that he went from Waddington to Marske in the northeast of Yorkshire on August 24, 1918, where he was presumably assigned to the No. 2 Fighting School.10

On September 25, 1918, Carpenter, along with fellow second Oxford detachment member Perley Melbourne Stoughton, joined the U.S. 166th Aero Squadron, a bomber and reconnaissance squadron outfitted with DH-4s. The 166th had that day, after a number of mix-ups, arrived at Maulan aerodrome to join the 1st Day Bombardment Group.11 Second Oxford men Albert Elston Weaver and John Joseph Devery were already at 166; Harrison Barbour Irwin, Linn Daicy Merrill, Phillips Merrill Payson and Foss would follow.12 In a letter home, Carpenter remarked: “When I got here I was very much surprised to find a lot of my original crowd in the squadron.” The Meuse-Argonne offensive began the day after Carpenter and the 166th arrived at Maulan, and Carpenter wrote: “We are on a red hot front, believe me; about as hot as anything could be.”13 The squadron, however, needed time to gear up before flying missions, and they did not participate in the bombing raids undertaken in late September and the first half of October by the 11th, 20th, and 96th Aero Squadrons, the three other squadrons in the 1st Day Bombardment Group.

The 166th’s first mission was on October 18, 1918; Carpenter flew with Richard Wilson Steele as his observer/gunner. A total of fifty-two planes—each of the four 1st Day Bombardment squadrons sending out a formation of ten to sixteen planes each—set off shortly after 2:00 p.m. to bomb Bayonville and Buzancy (approximately fifty miles to the north of Maulan). A number of planes failed to keep up for a variety of reasons, but the majority reached the targets around 3:30. The formations from the 11th, 20th, and 96th bombed Bayonville, while the 166th hit Buzancy. The 166th was attacked by a formation of Fokkers, and two planes were damaged, but all planes arrived back at Maulan at 4:00 p.m.14

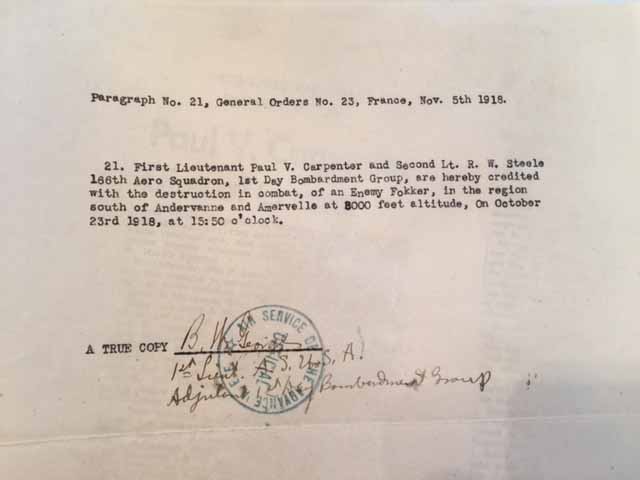

After this bad weather kept most planes grounded until October 23, 1918. On the 23rd Carpenter and Steel (in DH-4 32839), along with twelve other teams of pilots and observers from the 166th and similar numbers from the other three squadrons, set off at about 2:00 p.m. to bomb the Bois de Barricourt and nearby Buzancy and the Bois de la Folie. About half the planes from the 166th actually reached their objective and at 3:30 p.m. dropped 550 kilograms of bombs on the Bois de Barricourt. There they encountered not only “active and accurate” anti-aircraft fire, but also a formation of Fokkers, and the results of their dropped bombs were “unobserved on account of combat.” “During the course of the combat three of our [166th’s] planes were forced to land. They landed in control within our own lines.”15

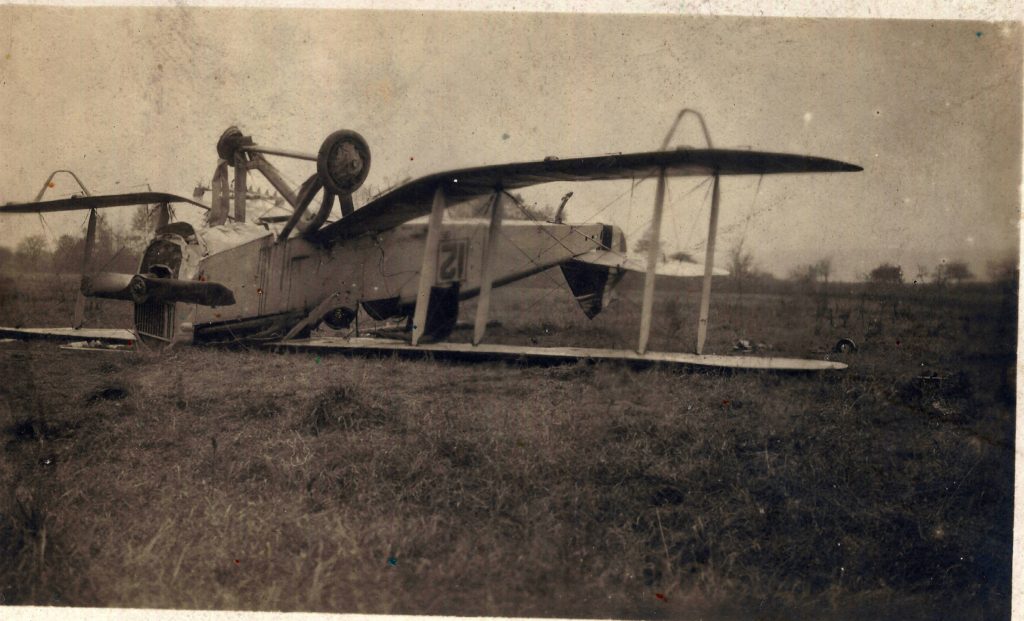

Carpenter’s plane was one of the three that “landed in control,” an evidently capacious concept. In a letter home he described how: “I went over on a raid, and when just above the objective, the Germans opened up an awful ‘Archie’ barrage (Anti-aircraft artillery) at our formation. Just after dropping our bombs one ‘Archie’ exploded right next to us. It blew out the side of the fuselage and I dropped about 800 feet out of control.” Carpenter’s plane thus damaged became easy prey for the Fokkers. “So they made up their minds to shoot Steele and me down as we were badly crippled and alone. So down they came, six of them to set about us.” Steele was wounded but managed to continue firing his gun as Carpenter struggled to get his crippled plane back over the lines. “I didn’t have an awful lot of control over [my plane], because she was all shot to pieces. I handled her the best I could, came down, hit some Boche wire, swung, hit a shell hole, and turned over, converting the buss into splinters. When we hit the shell hole we were going between 70 and 80 miles per hour so you can imagine what happened.”16

Thinking he was still in German territory, Carpenter was carrying his wounded observer towards cover in nearby woods when he was met by American soldiers. Steele was dispatched to a field hospital while Carpenter went back to examine his plane. Carpenter believed Steele had shot down two enemy planes; they received credit for the one that was confirmed.17

In a letter to Steele’s mother, Carpenter wrote that “throughout the entire fight [Steele] showed remarkable courage and has been recommended for the D.S.C.”18 Steele was indeed awarded a Distinguished Service Cross for “his extraordinary heroism in action” that day.19

Carpenter completed the letter to his own family describing his forced landing just before taking off on another raid on October 27, 1918, with a new plane (DH-4 31336) and a new observer/gunner, Ralph Owen Waltham. This time his was among the six (out of fifteen) planes that were not able to reach Briquenay, their objective.20 There were no missions flown the next day, but there were two on October 29, 1918, to both of which Carpenter and Waltham were assigned. Of the thirteen planes from the 166th that set out in the morning to bomb Montigny-devant-Sassey on the left bank of the Meuse, five, including Carpenter’s, did not reach the target.21 In the afternoon, however, as part of a combined mission of the four 1st Day Bombardment Group squadrons, Carpenter and Waltham in DH-4 31336 were among the ten planes from 166 that set off at 2:00 p.m. to bomb Damvillers, a town about six miles east of the Meuse. Their path took them initially north northeast thirty miles via Bar-le-Duc to Clermont where, flying at 12,000 feet, they turned east northeast to cross the Meuse near Gercourt. They reached Damvillers, dropped their bombs at 3:15, and were back at Maulan at 4:00 p.m.22

Carpenter, again flying DH-4 31336 with Waltham as his observer, set off on the morning of October 30, 1918, but his was one of two planes unable to reach the objective, Bayonville.23 This was apparently Carpenter’s last mission assignment; his experiences on the 23rd had apparently taken their toll. At the beginning of November 1918 he was ordered to a “rest chateau,” the Château de Cirey about thirty miles southwest of Maulan; the owner had put it at the disposal of the American Air Service to use as a convalescent home for aviators. Carpenter arrived on November 3, 1918, and remained there until December 10, 1918.24 His sister, Agnes Mary Carpenter, was at this time serving in the Red Cross and was stationed at Base Hospital 47 in Beaune, about ninety miles further south. Her passport application from late September of 1918 stipulated that she would “make no effort to visit my brother in France,” but one hopes the rules may have been bent.25

Carpenter returned to the U.S. on the U.S.S. Charleston, departing from Brest on January 31, 1919, and arriving at Hoboken on February 14, 1919.26 He was discharged on March 4, 1919, and returned to Milwaukee.27 For a time he worked as a bond salesman and as a reporter on the Milwaukee Sentinel, and then he returned to Europe. Having been too young for college before the war, he spent three years studying at Lincoln College, Oxford, in the early twenties. He then worked for a time in Europe for Swift International. Around 1928 he returned to Milwaukee and embarked on a career in marketing, advertising, and public relations.28

mrsmcq May 23, 2017; February 20, 2018

Notes

(For complete bibliographic entries, please consult the list of works and web pages cited.)

1 Carpenter’s date and place of birth are taken from Ancestry.com, Wisconsin, Birth Index, 1820-1907, record for Paul V Carpenter. His date and place of death are taken from Ancestry.com, Wisconsin Death Index, 1959-1997, record for Paul V. Carpenter. The photo was kindly supplied by Caroline Bergs, Carpenter’s great-niece.

2 Aikens and Proctor, Men of Progress, pp. 310–11.

3 Aikens and Proctor, Men of Progress, p. 311; Wikipedia, “Falk Corporation.”

4 A newspaper clipping titled “In the Aviation Corps” (date and source not known) describes his academic career through 1917. I am grateful to Caroline Bergs for sharing this and other newspaper clippings and documents about Carpenter.

5 A document written by Carpenter (a reimbursement claim for back pay and travel expenses) dated August 1, 1919, in the possession of Caroline Bergs, gives the date and place of his entering military service.

6 See War Mothers of America, Milwaukee County Chapter, handwritten and typewritten cards for Paul V. Carpenter, which provide some information on his early life, including his friendship with Cronin.

7 Murton Campbell, diary entries for September 27 and 28, 1917.

7a The list of men from Princeton selected by Springs that appears on p. 28 of Vaughn, War Flying in France, mistakenly includes Keenan and Knox. Neely’s diary entry for November 1, 1917, lists the Princeton men who did and did not go to Stamford.

8 “Cadets of Italian Detachment Posted Dec 3rd” in Foss, Papers. On No. 36 Squadron, see See Philpott, Birth of the Royal Air Force, p. 402, and Wikipedia, “RAF Usworth.”

9 Deetjen, diary, entry for March 29, 1918. And yes, spurs were a part of the Army uniform at this time, and the Signal Corps was part of the Army, so pilots theoretically wore spurs on their boots; Deetjen’s is one of the few references to this anachronistic apparel I have come across. And see Bingham, An Explorer in the Air Service, pp. 23-24.

10 The dates of his commission and his travel to Marske are taken from the previously cited reimbursement claim document. In cablegram 1047-S, dated May 3, 1918, he is recommended for his commission, “non flying”; the confirming cable, 1331-R, is dated May 16, 1918.

11 See “Roster of Commissioned Personnel of the 166th Aero Squadron”; Sloan, Wings of Honor, p. 359; and “The Squadron has an Eventful History.”

12 See “Roster of Commissioned Personnel of the 166th Aero Squadron.” Cronin, Carpenter’s friend and fellow member of the second Oxford detachment, had been assigned to the 96th Aero Squadron and thus also to the 1st Day Bombardment Group. Cronin was killed returning from a mission thirteen days before Carpenter’s arrival at Maulan.

13 Excerpts from Carpenter’s letters home were printed in “Milwaukee Man Lost in Clouds.”

14 Rath, “First Day Bombardment Group, Account of Operations,” pp. 129–30, and Hicks, “History of Operations of the 166th Aero Squadron” p. 85.

15 The first two quotations are from p. 133 of Rath, “First Day Bombardment Group, Account of Operations”; the third is from Hicks, “History of Operations of the 166th Aero Squadron,” p. 85. One of the other planes forced to land was that flown by Fremont Cutler Foss; I have not been able to discover who piloted the third. See also the account of this mission on pp. 58 and 60 of Richardson “The Wartime Diary of Clifford Allsopp—Bomber Pilot”; unfortunately Richardson does not provide sources, although one is likely to have been the diary of Allsopp. Allsopp, according to his Carnet (log book) did not participate in the mission, but would surely have been told about it.

16 Carpenter’s letter is reproduced in “Lt. Carpenter Pilots Plane through Inferno of Gunfire.” At least two photos were taken of the flipped plane and are included, unlabeled, in the photo album of Paul James McWilliams, a sergeant with the 166th; in another album, in the possession of Chuck Thomas, the photos are labeled “Steele’s crash.” See Thomas and O’Neal, “The 166th Aero Squadron – A History in Photos,” for photos from the two albums.

17 For the victory credit, see Sherman, comp., Operations of Air Service, First Army from August 10th to November 11th, 1918, p. 87, where for “Andervanne” read “Andevanne.”

18 Carpenter’s letter is quoted in “[Distinguished] Service Medal”

19 See “Richard Wilson Steele.”

20 Rath, “First Day Bombardment Group, Account of Operations,” p. 135.

21 Rath, “First Day Bombardment Group, Account of Operations,” p. 136.

22 Hicks, “History of Operations of the 166th Aero Squadron,” p. 107.

23 Rath, “First Day Bombardment Group, Account of Operations,” p. 138.

24 “Rest Chateau,” p. 86.

25 See War Mothers of America, Milwaukee County Chapter, [card for Agnes Mary Carpenter]; Ford, Administration American Expeditionary Forces, p. 673; and Ancestry.com, U.S. Passport Applications, 1795-1925, record for Miss Agnes Mary Carpenter.

26 War Department, Office of the Quartermaster General, Army Transport Service, Lists of Incoming Passengers, 1917 – 1938, Passenger list for Casual Detachments, on U.S.S. Charleston.

27 The date of his discharge is taken from the reimbursement claim document dated August 1, 1919, cited above.

28 See his 1921 passport application, Ancestry.com, U.S. Passport Applications, 1795-1925, record for Paul V Carpenter, where he lists himself as a bond salesman; other information about his post-war life is taken from “Paul V. Carpenter Dies of Cancer.”