(Xenia, Ohio, April 19, 1888 – Xenia, Ohio, June 1, 1966).1

Kelly’s paternal grandfather, born and raised in Ireland, brought skills related to cloth manufacturing to the U.S. in 1859, initially settling in New Jersey, where Kelly’s father was born, and then moving to Ohio, where he developed machinery for manufacturing hemp twine.2 Kelly’s mother, Rachel Josephine Kelly, née Corry, came from a well-to-do farming family; her father had come to Xenia from Pennsylvania at a young age.3

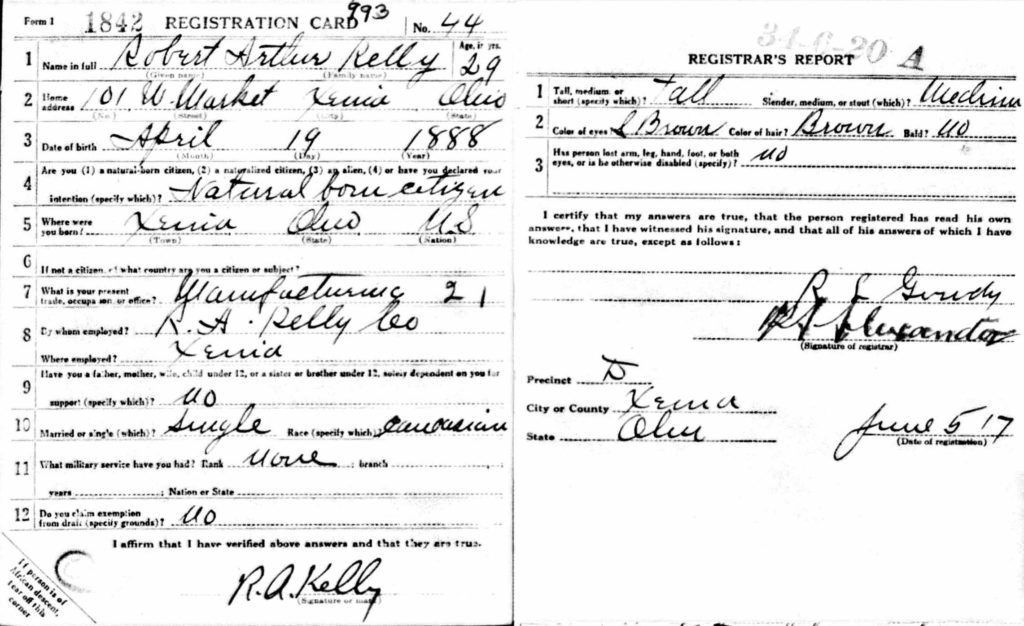

Kelly initially enrolled in the College of Wooster in Ohio but transferred to Yale’s Sheffield Scientific School, where he joined the Aero Club and sat on the club’s governing board.4 The high spirits and high jinks that later figured in Elliott White Springs’s accounts of Kelly were already in evidence at Yale: in 1910 Kelly was one of four Sheffield men suspended for “borrowing” a classmate’s automobile.5 Evidently reinstated, Kelly graduated in 1911. In about 1914, suffering from tuberculosis, he spent some time in Arizona.6 By 1917 at the latest, when he registered for the draft, he was back in Ohio and employed at R. A. Kelly Co, the family cordage manufacturing firm.7

Kelly attended the School of Military Aeronautics at Ohio State University in the summer of 1917, graduating on August 4, 1917, and then proceeding to a Signal Corps Aviation school nearby for primary flight instruction.8 At the beginning of September Kelly was sent to Mineola and assigned to a group of 150 men going to Italy for flight training. Members of the “Italian detachment” boarded the Carmania at New York on September 18, 1918, and set sail initially for Halifax. There they joined a convoy for the Atlantic crossing, which took just under two weeks. On board, Kelly found kindred spirits in Springs and Allen Tracy Bird, although the former, being in charge of the group, made an effort to keep the shenanigans under control: “We have an ex-cowboy with us named Bird, who has been having a terrible time behaving himself. Bob Kelly was a cowboy out in Arizona for a while when he was trying to shake off the con and every time they get together the storm clouds gather. They are good friends of Springs’s and whenever they get started he joins them and tries to quiet things down.”9

Arrived at Liverpool on October 2, 1917, the men were informed that they would not be going to sunny Italy as anticipated, but were put immediately on a train for Oxford where they would attend ground school, again. They had to leave most of their baggage in Liverpool, and “Springs left Kelly in charge of it and he picked Bird and [Earl] Adams and [Stanley Cooper] Kerk to stay with him to help. I’ll bet they don’t show up for a month.”10 Not a month, but a week later, “Kelly and his squad arrived to-day with our baggage. They look like they had a good time. Bird was telling some story about their driving a coach until Kelly fell through the top of it.”11 October 1917 entries in War Birds include a number of passages recounting drinking and partying centered on Bird and Kelly. “ Kelly and Bird go out every night and take off their white hat bands [which marked them as cadets] and say that they are mechanics from this squadron outside of town. They throw a big party and then come in and wake Springs up to tell him about it because they say they don’t want to do anything behind his back that they wouldn’t tell him about to his face.”12

At the beginning of November places became available for flight training at Stamford, and Springs had to choose twenty men out of the 150, all of whom were eager to get flying. Kelly was among those Springs selected, probably because he, like a number of the others, had had some flight training already. Even without Bird—who left with the rest of the detachment for machine gun school at Grantham on November 3, 1917—Kelly and Springs did their best to get into trouble, coming back from Abingdon very late their last night in Oxford and breaking the tree limb used for after-hours entrance into their college: “limb Kelly and all landed right on my belt buckle. Funny? We couldn’t move for half an hour and then we had to build a sort of ladder out of the broken limb to get in.”13

Once at Stamford, Kelly and Springs roomed together. Springs wrote home that “[w]e have very nice quarters here. Two of us are living over a little millinery shop on High Street. My roommate is a prince. Three years ago he went out to Arizona to die with consumption. He’s now the healthiest specimen you ever saw. I call him Morituri.”14 They partied together and, when weather permitted, trained on Curtiss JN-4s. There was presumably some initial dual instruction, but, assuming Kelly’s experience resembled Springs, he put in many hours flying solo. He may, like Springs, have started flying DH.6s early in the new year.15 Springs’s diary entry for January 5, 1918, indicates that Kelly, along with James Ernest Roth, was posted from Stamford to another training field, apparently, according to a passing reference in War Birds, Harling Road in Norfolk.16 Springs mentions planning to visit Kelly there in a letter dated January 20, 1918.17

By early March 1918 Kelly had advanced sufficiently to be recommended for a commission. Pershing’s cable conveying the recommendation to the War Department is dated March 14, 1918; the confirming cable is dated March 26, 1918.18 Kelly was still (or again) at Harling Road on April 5, 1918, when he was placed on active duty.18a As far as I can tell, the only training provision at Harling Road was No. 10 Training Depot Station, which prepared pilots for daylight bombing on DH.4s and DH.9s.18b I have found no further information on Kelly’s training, but, given that he was later assigned to S.E.5 squadrons, he must have received some training at a station or stations other than Harling Road.

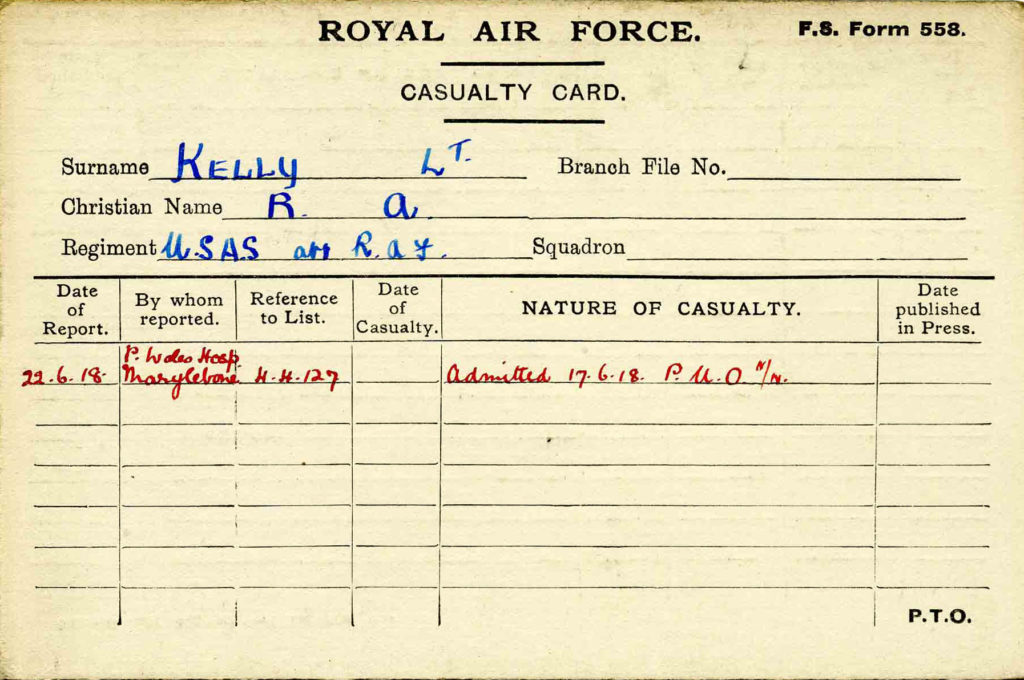

In a letter probably from early June 1918, Springs remarks that “I had a letter from Kelly from England today and he hopes to be ready to come out in a week or so. The Major is going to try to get him here.”19 Springs was evidently hoping that Billy Bishop, C.O. of No. 85 Squadron R.A.F., could pull strings to get Kelly assigned to 85, where Springs, John McGavock Grider, and Laurence Kingsley Callahan had been since early May. However, this was not to be. On June 16, 1918, Kelly was admitted to the Prince of Wales Hospital in London, apparently suffering from fever.20 By June 23, 1918, he was well enough to have dinner in London with Marvin Kent Curtis.21

In September Springs was once again (or still) trying to get Kelly into his squadron, which was now the U.S. 148th Aero: “Am trying to get Bob Kelly for the eighth [148th?]. He’s still in hospital in London from his crash but ought to be out shortly.”22 I have not been able to find a casualty card related to a crash involving Kelly.

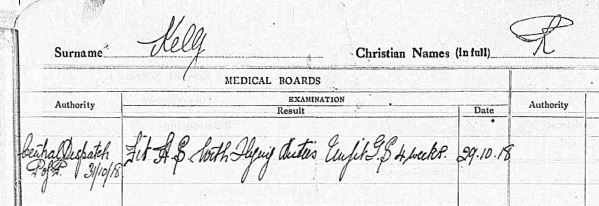

Kelly’s very sketchy R.A.F. service record suggests he continued to have health problems. A medical exam on October 29, 1918, reports that he was “Fit H[ome] S[ervice] with flying duties. Unfit G[eneral] S[ervice] 4 weeks.”23

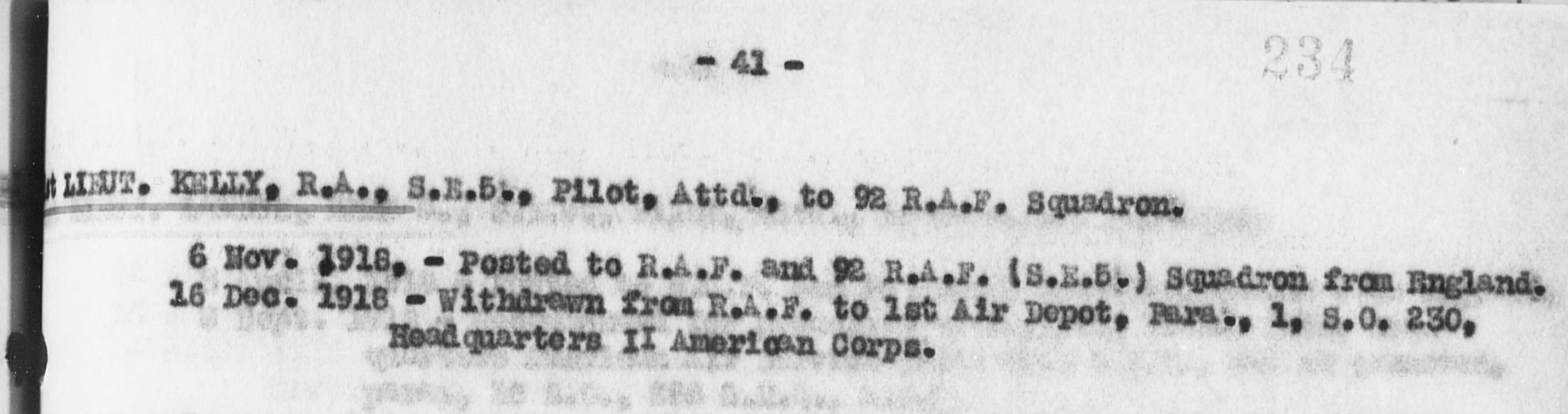

Nevertheless, on November 7, 1918, he was sent to France, to No. 2 A.S.D., i.e., the pilots pool south of Boulogne, where he remained for a little over the month, well beyond the armistice.24 Finally, on December 12, 1918, he went to No. 92 Squadron R.A.F., an S.E.5 squadron, but he was almost immediately transferred to the A.E.F.25 According to one source, he reported to the (American) 1st Air Depot at Colombey-les-Belles on December 16, 1918.25a From there he was apparently assigned, like a number of other second Oxford detachment members, to the U.S. 25th Aero—the only U.S. squadron to be equipped with S.E.5s.26

On March 15, 1919, Kelly embarked on the S.S. Roma at Marseilles and sailed for home, arriving at Brooklyn on April 4, 1919.27 He returned to Xenia and was for a time associated with the family cordage business.28 Active as a reserve officer, he attained the rank of major.29 In the 1930s he was a founding partner of the Kelly-Creswell Company, which still manufactures pavement striping equipment.30 Spings’s continued regard for Kelly is evident in Springs’s dedication to him of a short story, “Long Distance,” which is among the stories in the 1927 collection, Nocturne Militaire.

mrsmcq May 25, 2018; updated June 22, 2021, to include photo and to reflect casualty form information

Notes

(For complete bibliographic entries, please consult the list of works and web pages cited.)

1 For Kelly’s place and date of birth, see Ancestry.com, U.S., World War I Draft Registration Cards, 1917–1918, record for Robert Arthur Kelly. For his place and date of death, see “R. A. Kelly is Claimed at Hospital.” The photo is one kept by John Chadbourn Rorison and reproduced on p. 50 of Doyle, “War Birds Pictorial” (where the caption apparently incorrectly associates him with No. 94 Squadron R.A.F.). My thanks to the League of WW 1 Aviation Historians for permission to use the photo here.

2 See “Robert A. Kelly,” an obituary for Robert Alexander Kelly.

3 See documents available at Ancestry.com.

4 See The College of Wooster, Catalog of the Alumni Faculty and Officers 1870–1916, p. 100; and The Yale Banner and Pot-Pourri 1910–1911, pp. 366 and 441.

5 “Xenia Boy in College Prank.”

6 Springs, Letters from a War Bird, p. 57; see also the entry for September 29, 1917, in War Birds with the reference to Kelly “trying to shake off the con,” where “con” is presumably short for “consumption.”

7 See Kelly’s World War I draft registration, cited above.

8 See “151 Cadet Aviators Graduated” and Ancestry.com, Ohio Soldiers in WWI, 1917–1918, record for Robert A. Kelly.

9 War Birds, entry for September 29, 1917.

10 Ibid., entry for October 3, 1917.

11 Ibid., entry for October 8, 1917.

12 Ibid., entry for October 22, 1917.

13 Springs, Letters from a War Bird, p. 53.

14 Ibid., p. 57.

15 See the flight log transcriptions in Chapter 3 of Springs, Letters from a War Bird.

16 For Springs’s diary entry, see Springs, Letters from a War Bird, p. 71; War Birds, entry for January 31, 1918.

17 See Springs, Letters from a War Bird, p. 78, where I believe “Harbury” is a mistranscription for “Harling.”

18 Cablegrams 731-S and 985-R.

18a Biddle, “Special Orders No. 35.”

18b On Harling Road and No. 10 T.D.S., see “Feltwell & Harling Rd aerodromes.”

19 Springs, Letters from a War Bird, p. 148.

20 See “Kelly, R. A.” I read the “Nature of Casualty” entry in part as “Admitted 17.6.18 P.U.O.” and take “P.U.O.” to mean “pyrexia of unknown origin.”

21 Curtis, letter of June 23, 1918.

22 Letter of September 12, 1918, p. 229 of Springs, Letters from a War Bird.

23 See The National Archives (United Kingdom), Royal Air Force officers’ service records 1918–1919, record for R. A. Kelly.

24 See “Lieut. R. A. Kelly U.S.A.S.”

25 Ibid.

25a See the entry for Kelly on p. 234 (41) of Munsell, “Air Service History.” The account in The Official Roster of Ohio Soldiers, Sailors, and Marines in the World War, 1917–18 differs; see Ancestry.com, Ohio Soldiers in WWI, 1917–1918, record for Robert A. Kelly.

26 On Kelly’s assignment to the 25th, see Sloan, Wings of Honor, pp. 206 and 221; Ancestry.com, Ohio Soldiers in WWI, 1917–1918, record for Robert A. Kelly; and Nettleton, Yale in the World War, vol. 2, p. 351. Kelly’s name does not appear on rosters for the 25th in Sloan, Wings of Honor, pp. 387–88 and 428–29, or “History of 25th Aero Squadron, (Pursuit).”

27 War Department, Office of the Quartermaster General, Army Transport Service, Lists of Incoming Passengers, 1917 – 1938, Passenger list for Casuals, on S. S. Roma.

28 Ancestry.com, 1920 United States Federal Census, record for Robert A Kelly.

29 “Men and Matters.”

30 “R. A. Kelly is Claimed at Hospital.”