(Boonsboro, Maryland, November 12, 1895 – Roanoke, Virginia, January 2, 1971).1

Both of Martz’s parents were born in the western Maryland town of Boonsboro. His father, Franklin W. Martz, a fruit farmer, was descended from German Mennonite immigrants to Pennsylvania who relocated to Washington County in Maryland. The senior Martz married Mary Victoria Hoffman, and the couple had two children, Roger Edwin and his younger sister Mary.2

Roger Edwin Martz attended Johns Hopkins University where he studied electrical engineering.3 He worked for a time, perhaps during summers, in the electrical department of Baltimore’s Consolidated Gas & Electric Company.4 About a month before registering for the draft on June 5, 1917, he, along with Louis McComas Young (also from Boonsboro and a year ahead of him at Hopkins), went to Washington to apply for the Aviation Section of the Signal Corps.5

They were successful and that summer entered the School of Military Aeronautics at Ohio State University, where a number of other young men from Maryland were also enrolled. Frederick Joseph Seligman, who later became a White House press photographer, took a photo of sixteen Marylanders at O.S.U. S.M.A., including Martz and Young, in early August 1917, and it was published in the Baltimore Evening Sun on August 7, 1917, under the title “Maryland Boys To Fly In France.” The rumor around that time was that the top men in the ground school classes would go to France for their advanced training. The two “Maryland Boys” from the ground school class of September 1, 1917, Martz and Young, stood side by side for the official graduation group photo.

By this time Italy had replaced France as the expected site for advanced training, and, along with most of their O.S.U. classmates, Martz and Young chose or were chosen to train there. They thus joined the 150 men of the “Italian” or “second Oxford detachment” who arrived at Mineola on Long Island in early September and then boarded the Carmania at New York and set sail September 18, 1917. After a stopover at Halifax, where the Carmania joined a convoy for the Atlantic crossing, they sailed for Europe on September 21, 1917. When the Carmania docked at Liverpool on October 2, 1917, the detachment learned to their initial consternation that they were not to proceed further to Italy, but to remain in England, where they would repeat ground school at the Royal Flying Corps’s No. 2 School of Military Aeronautics at Oxford University.

In early November about twenty men were selected by Elliott White Springs, who was in charge of the men, to begin flight training at Stamford. The remaining men, including Martz, were ordered to a machine gun school, Harrowby Camp, near Grantham in Lincolnshire; there were not enough R.F.C. squadrons to accommodate all the Americans.

After two weeks, places again opened up for some of the men to go to squadrons and to begin flying instruction, but again, most of the men, including Martz, remained for another two weeks of gunnery instruction at Grantham.

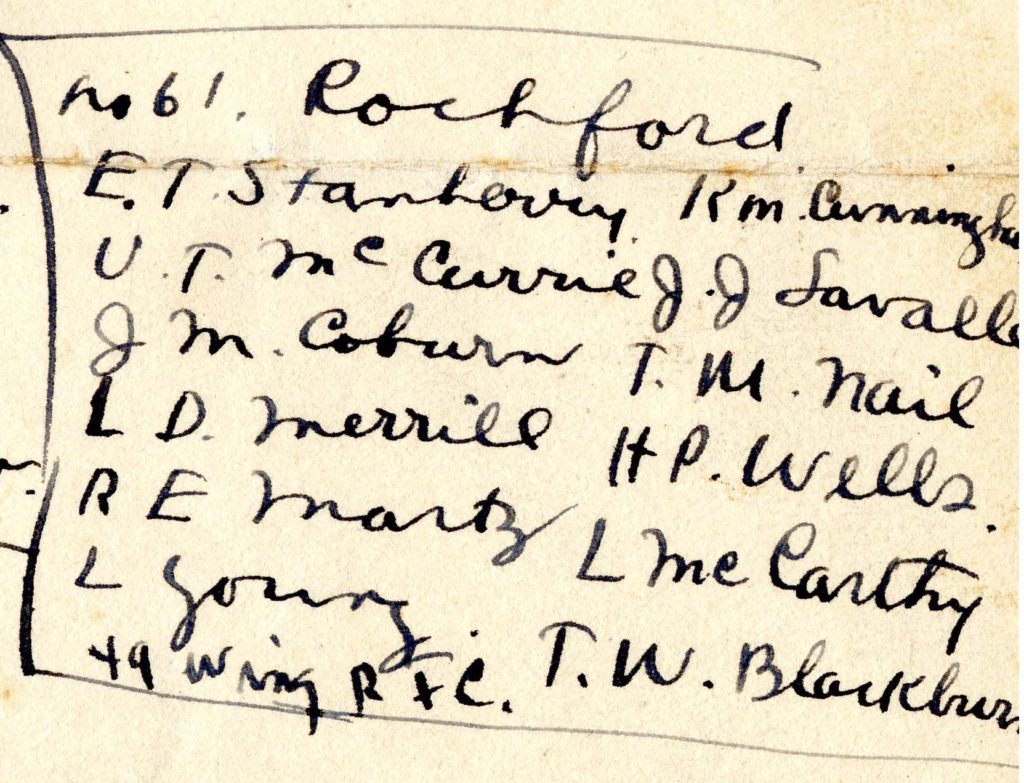

At the beginning December, finally, the men still at Grantham were posted to training squadrons. Martz, along with Young, was among a group of twelve men assigned to No. 61 Squadron at Rochford in Essex (the others were Elwood D. Stanbery, Uel Thomas McCurry, James Mitchell Coburn, Linn Daicy Merrill, Kenneth MacLean Cunningham, John Lavalle, Thomas M. Nial, Horace Palmer Wells, Leo McCarthy, and Thomas Welch Blackburn).6 No. 61 was a home defense squadron flying S.E.5a’s, but Rochford had for some time also been used for pilot instruction, and there were evidently training aircraft available.7

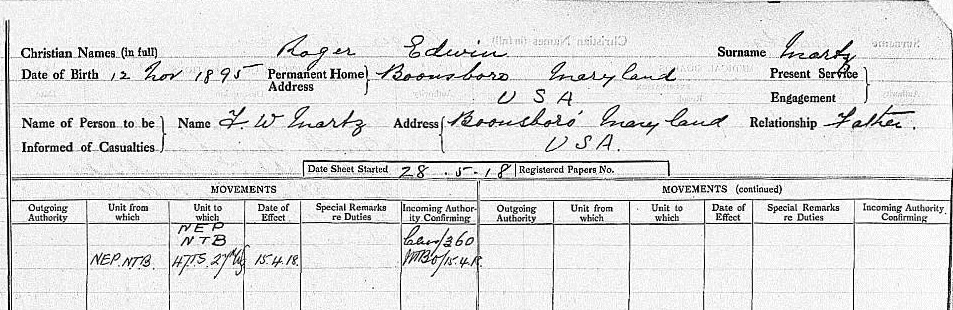

Information on Martz’s further training is sketchy. His RAF service record notes his having had “4 hrs dual on Avro,” but also notes that he was “NEP NTB.”8 The abbreviations probably stand for “non-effective pool, Northern Training Brigade,” suggesting that for some time prior to April 1, 1918 (when the Northern Training Brigade was renamed), Martz was stationed at a squadron in the Northern Training Brigade area (probably in Lincolnshire), but was ill or for some other reason on non-flying status. The service record indicates that in mid April 1918 he was posted to No. 47 Training Squadron at Waddington in Lincolnshire, about twenty miles north of Grantham.

Martz had just been recommended for his commission, one in a long list of men from the second Oxford detachment recommended by General Pershing as “First Lieutenants Aviation Reserve non flying” in a cablegram dated April 8, 1918.9 In an earlier cable to Washington, dated March 13, 1918, Pershing had described the situation of the approximately 1400 aviation cadets in Europe, some of whom had waited three months to start flying instruction, and some of whom, after five months, were still waiting and might have to wait another four. “All of those cadets would have been commissioned prior to this date if training facilities could have been provided. These conditions have produced profound discouragement among cadets.” To remedy this injustice, and to put the European cadets on an equal footing with their counterparts in the U.S., Pershing asked permission “to immediately issue to all cadets now in Europe temporary or Reserve commissions in Aviation Section Signal Corps.”10 Washington approved the plan in a cable dated March 21, 1918, but stipulated that the commissioned men be “put on non-flying status. Upon satisfactory completion of flying training they can be transferred as flying officers.”11

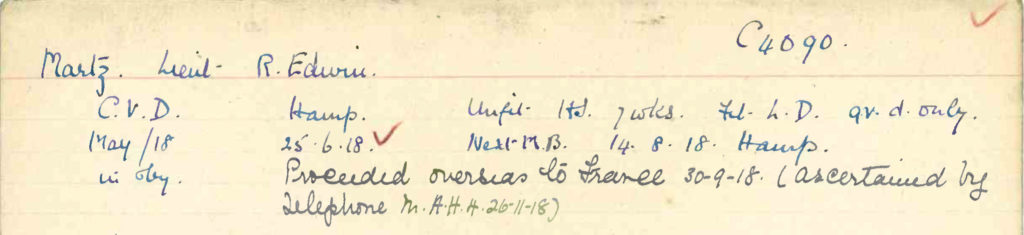

Martz was one of a handful of men from the thirty-eight second Oxford detachment members named in Pershing’s cable of April 8, 1918, who were not “transferred as flying officers,” although his commission was among those approved in a cablegram from Washington dated May 13, 1918.12 A medical card for him notes that in May 1918 he was diagnosed with “C.V.D.,” presumably color vision deficiency.13

Writing just after the war about the “Selection of Candidates for Aviation,” surgeon, pilot, and officer Henry Graeme Anderson noted that “Pilots and observers should have perfect colour vision. The importance of this is seen in picking out the colour or markings of hostile machines, in recognising signal lights, and in judging the nature of landing grounds.”14 It was presumably the diagnosis of color blindness that resulted in Martz’s being declared “Fit L[ight] D[uties] gr[ound] d[uties] only” when his medical examination was written up on June 25, 1918, surely a great blow and disappointment to him.

I have found no record of what Martz’s “light duties” were, but he presumably had either an administrative position or perhaps one that took advantage of his electrical engineering background. There is also no record of the result of his next scheduled medical examination on August 14, 1918. However, his R.A.F. medical card notes that on September 30, 1918, he “proceeded overseas to France.” By mid-October he was apparently at the 3rdAviation Instruction Center at Issoudun.15 A history of the U.S. 33rd Aero Squadron, which was based at Field 9 of 3 A.I.C., notes that Martz was assigned to the squadron and the field in November 1918.16 Although the 33rdAero was not at the front, it performed vital duties ensuring that facilities and planes were maintained and that instruction, mainly on Nieuports, could proceed expeditiously. A list of officers from shortly after the armistice indicates that Martz served as chief engineer officer of the 33rd Aero.17

Martz was able to return to the U.S. fairly quickly after the armistice. The manifest for the S.S. Northland when it departed from Brest on February 8, 1919, includes him among the officers with the rank of captain, indicating that Martz had received a promotion while still in Europe.18 He had left Johns Hopkins at the end of his junior year, but Hopkins, like many universities, made special provisions for students like Martz and had granted him a B.S. in engineering extra ordinem in June of 1918.19 Somewhat surprisingly, instead of continuing in engineering, Martz took up a career in public school education and then worked in vocational rehabilitation for the Veterans Administration.20

Notes

(For complete bibliographic entries, please consult the list of works and web pages cited.)

1 Martz’s place and date of birth are taken from Ancestry.com, U.S., World War I Draft Registration Cards, 1917–1918, record for Roger Edwin Martz. His place and date of death are taken from Ancestry.com, Virginia, Death Records, 1912–2014, record for Roger Edwin Martz. Note: Martz is listed in the “Roster of Second Detachment” and the “Roster from Clayton Knight” as “Roy E. Martz,” and in the “Passenger list[s] for Aviation Section, Signal Corps, on Carmania, sailing Sept. 18, 1918” (see Ancestry.com, Lists of Outgoing Passengers, 1917 – 1938) as “Martz, R. E.” and “Martz, Roye E.” The photo is taken from Fremont Cutler Foss’s copy of the O.S.U. Squadron 8 graduation photo.

2 On Martz’s descent and family, see documents available at Ancestry.com.

3 See Martz’s draft registration card, cited above.

4 See The National Archives (United Kingdom), Royal Air Force officers’ service records 1918–1919, record for Roger Edwin Martz.

5 “Would Join Flying Corps.”

6 Foss, Papers, “Cadets of Italian Detachment Posted Dec 3rd.”

7 Philpott, The Birth of the Royal Air Force, pp. 250–51.

8 See Martz’s R.A.F. service record, cited above.

9 Cablegram 874-S.

10 Cablegram 726-S.

11 Cablegram 955-R.

12 Cablegram 1303-R.

13 I am grateful to the RAF Museum, London, for a scan of Martz’s medical card. I should note that it is possible that the abbreviation stands for “cardio-vascular debility.”

14 Anderson, The Medical and Surgical Aspects of Aviation, p. 31.

15 See the entry for Martz in Maryland War Records Commission, Maryland in the World War, 1917–1919.

16 “33rd Aero Squadron (Training),” p. 9 (277).

17 Ibid. See also, Bingham, An Explorer in the Air Service, p. 249.

18 See War Department. Office of the Quartermaster General, Army Transport Service, Lists of Incoming Passengers, 1917 – 1938, Passenger list, Officers, S. S. Northland, departing Brest February 8, 1919, arriving Philadelphia February 21, 1919.

19 “Hopkins Finals Held,” p. 5. Hopkins later evidently lost track of Martz, reporting in 1920 that he was an “Ensign, Naval Aviation, Italy.” See Johns Hopkins University, Report of The Johns Hopkins University to the General Assembly of Maryland, p. 24.

20 See Ancestry.com, 1930 United States Federal Census, record for Roger E Martz, and “New Director on Inspection Tour.”