(Huntsville, Arkansas, July 17, 1889 – Los Angeles, January 16, 1959).1

Background ✯ Oxford & Grantham ✯ Rochford & further training ✯ 8th Aero Squadron ✯ 11th Aero Squadron

Background

The families of both McCurry’s father, Benjamin Crawford McCurry, and his mother, the former Ella I. Sams, had roots in the American south back at least to the mid-eighteenth century. Nevertheless, McCurry’s grandfather, Georgia-born Daniel Newnan McCurry, is to be found on the rolls of Tennessee’s Union soldiers.2 McCurry’s father, who went by “B. C. McCurry,” was a grocer and a Methodist clergyman active in Huntsville, Arkansas. He, his wife, and their son and two daughters relocated to Spokane, Washington, in about 1899.3 (The older daughter died in 1901, apparently while the family was back in Arkansas).4

McCurry’s unusual first name appears to have been chosen from one of the more obscure lists of biblical “begats.” Newspapers and other written sources have difficulties with it, and he sometimes appears as “Euel,” “Ewell,” “Ulo,” “Vel,” or “Ned,” or, simply and safely, as “U. T.”

Like most of the other second Oxford detachment members, McCurry was athletic, and there is a 1908 newspaper article that describes him as captain of the indoor baseball team at Spokane’s Blair Business School.5 In the fall of that year he began attending the University of Idaho, where he joined the Kappa Sigma fraternity; he was initially a student of agriculture and then in the newly-founded Department of Forestry.6 I have been unable to find a record of his graduation. By the spring of 1914, he was back in Spokane and president of the Y.M.C.A. tennis club.7 In 1916 his name appears in connection with mining in British Columbia, and he became associated with the H. T. Irvine Co., a mining brokerage in Spokane.8 In April 1917 McCurry joined with Herbert Thomas Irvine and naval architect Harry Bingham Spear to form the ambitious West Coast Ship Building company.9 It was perhaps just as well that around this time McCurry applied for the Aviation Section of the Signal Corps and was accepted, thus cutting short his business association with Irvine—who two years later fled to Mexico because of “irregularities in the office” of his eponymous company.10

McCurry attended ground school at the University of Illinois at Champaign; his name appears in lists of the graduating classes of both August 25 and September 1, 1917.11 From Illinois, he travelled to New York in September; he had chosen or been chosen to continue his training in Italy and thus sailed to Europe on the Carmania with the 150 men of the “Italian” or “Second Oxford Detachment.” They departed New York on September 18, 1917, bound initially for Halifax, where they joined a convoy that set off across the Atlantic on September 21, 1917.

Oxford & Grantham

When, after an uneventful voyage, their ship docked at Liverpool on October 2, 1917, the men found that they would not continue to Italy, but would remain in England and attend ground school (again) at the Royal Flying Corps’s No. 2 School of Military Aeronautics at Oxford University. Like most of the men, McCurry made his peace with the change of plans; classes were not very demanding, and autumn in England a pleasure. There were trips through the surrounding countryside—a photo kept by John McGavock Grider captures McCurry and fellow detachment members Charles Edward Brown and Hugh Douglas Stier dismounted from their bicycles during a trip to a nearby village.12 McCurry wrote his mother that “Our sleeping quarters and food are excellent. . . . It is quite damp and cold here, but we are provided with good equipment and keep warm. One of the things we can’t get used to is drinking tea for breakfast, but suppose it will gradually become a habit. Haven’t any idea where we go from here for our flying training.”13

Flying training was still weeks away. There not being openings in R.F.C. squadrons, most of the men, including McCurry, were sent from Oxford to a machine gun school, Harrowby Camp, near Grantham in Lincolnshire at the beginning of November. Fifty of them were posted to squadrons in the middle of the month, but the rest, again including McCurry, continued at Grantham through Thanksgiving. Finally, on December 3, 1917, the remaining men were assigned to squadrons.

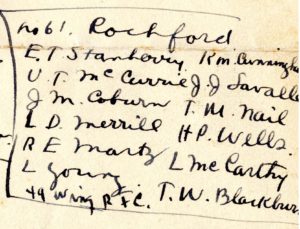

McCurry was in a group of twelve posted, at least initially, to No. 61 Squadron, a home defense squadron in Rochford in Essex.14 Quickly, however, some, including McCurry, or perhaps all of them, were (re)assigned to No. 198 Night Training Squadron, which shared the airfield with No. 61 and which had Avros for training purposes.15 In December 1917, in a letter home, McCurry wrote enthusiastically about his situation: “I am having the time of my young life in spite of cold weather. Am billeted at the West Cliff hotel, Westcliff-on-Sea, near South End, Essex. I go to and from the aerodrome in a machine. Am flying every day and expect to have a machine of my own the last of this week. My instructor says I am doing fine and am pretty sure to land a fighting scout instead of one of the slower bomb droppers or artillery observation machines. Gee, but you should have seen what I have been through to get there. But, after all, it has its reward, for I am living like a prince.” He also gave a brief account of a December 6, 1917 German raid on England: “In a raid a few days ago a big Gotha bomber was dropped down at our aerodrome. I am sending you a piece of the fabric from one of the wings. You will note the blue coloring, which is camouflage used to lessen the visibility. The crew of three Huns were only slightly damaged and made fine prisoners. The English did might[y] good work and only slight damage was done.”16

While many of McCurry’s fellow cadets made slow progress in their training because of poor weather and an inadequate number of planes, he was more fortunate, although he still felt that things did not move very fast. On January 20, 1918, still at Rochford, he wrote a friend at the H. T. Irvine Co. that “I have passed my flying tests for a commission as first lieutenant. It has been a long and steady grind. Although it has been very slow I am glad to have received the training under the royal flying corps as the machines are superb and the instructors excellent.” Apparently referring to the twelve cadets stationed at Rochford, he writes that “Of the 12 I was one of four recommended as first class pilot for fighting scouts and am a fair stunt merchant now. I shall get my commission as first lieutenant in February, I suppose.”17 McCurry was among the earliest of the second Oxford detachment men to be recommended for a commission as a first lieutenant. Nevertheless, it was not until February 16, 1918, that Pershing forwarded the recommendation to Washington, and the confirming cable from Washington was only sent March 1, 1918.18 McCurry was placed on active duty on March 20, 1918.19

From Rochford McCurry was transferred on January 26, 1918, to Boscombe Down on Salisbury Plain in Wiltshire, presumably to No. 6 Training Depot Squadron, and this suggests that he, contrary to his expectations, had been selected as a bomber or observation pilot. The planes available were (in addition to Avros) B.E.2c’s, B.E.2e’s, and DH6s—all two seaters designed or now used for training—and DH.4s, DH9s, and FK8s, two-seater operational aircraft used for reconnaissance and bombing.20 In a letter written from Salisbury in March 1918 McCurry reported that “I am flying the fastest bus they have in the royal flying corps now”—probably referring to the DH.4, which could, under certain conditions and in its best configuration, achieve a speed of 143 m.p.h.21 McCurry also remarks in this letter that “Two more men of our branch have been killed recently.” It is uncertain what is meant by “our branch,” but he was perhaps referring to second Oxford detachment members Lloyd Ludwig and George Orrin Middleditch, who died on February 28 and March 12, 1918, respectively, the seventh and eighth men of the detachment to die in crashes.22

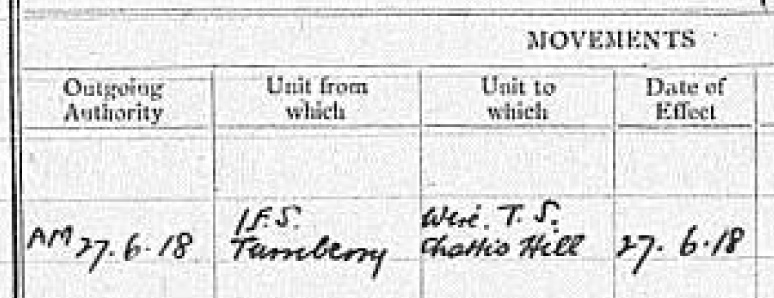

McCurry probably continued his training at Boscombe Down through May or perhaps early June. At some point he was assigned to the No. 1 Fighting School at Turnberry on the west coast of Scotland. From there, on June 27, 1918, he went to the W[ireless] T[elephony?] School at Chattis Hill in Hampshire.23

In early July 1918 McCurry was among a group of pilots ordered to proceed from London to the 3rd Aviation Instruction Center at Issoudun in the Loire region of central France.24 During his time at 3 A.I.C. he probably became familiar with the DH-4, the American-built version of the British DH.4.

8th Aero Squadron

McCurry is next documented as reporting to the U.S. 8th Aero Squadron on August 21, 1918.25 Curiously, his name does not appear on a roster of officers present on September 10, 1918, although those of the six other second Oxford detachment members (Newton Philo Bevin, Edward Addison Griffiths, Anker Christian Jensen, Edward Russell Moore, John Howard Raftery, and Hilary Baker Rex) who reported around the same time do.26

The 8th was an observation squadron flying DH-4s; it had been at Amanty since the last day of July, attached to the I Corps Air Service of the American First (and at that time only) Army. On August 31, 1918, as part of the planning for the St. Mihiel Offensive, the 8th Aero was transferred to IV Corps and moved to Ourches-sur-Meuse, about eight miles due west of Toul, where the IV Corps Air Service was based.27 The offensive to reduce the St. Mihiel salient began in the early hours of September 12, 1918. The 8th Aero was assigned to assist the IV Corps’s 1st Division, which was at the westernmost part of the American line on the south front of the salient. The squadron C.O., John Gilbert Winant, reported that on the 12th and 13th planes of the 8th Aero “were in the air for thirty-six hours and thirty minutes . . . and twenty-four separate missions were accomplished.”28 In a letter to H. T. Irvine dated October 14, 1918, McCurry recalls that he “Was with an observation squadron during the St. Mihiel and Thiaucourt show.”29 Unfortunately, the 8th Aero Squadron is not well documented, and I have been unable to find operations reports that might provide details of individual flights and thus document McCurry’s participation.

On September 21, 1918, McCurry was dropped from the 8th Aero rolls and admitted to Base Hospital 51 at Toul. The annotation “Not L/D” in the entry for him in the squadron’s “Losses in commissioned personnel during September, 1918” list perhaps means that his medical problem was not sustained in the line of duty.30

11th Aero Squadron

In his letter to Irvine of October 14, 1918, McCurry recounts how, after the St. Mihiel Offensive, he “was transferred to this squadron as the C.O. was an old pal.” “This squadron” was the U.S. 11th Aero, to which McCurry was assigned on September 25, 1918,30a and the “old pal” was McCurry’s fellow second Oxford detachment member Charles Louis Heater, whom McCurry presumably knew not only from the Carmania, Oxford, and Grantham, but also Boscombe Down, Turnberry, and Chattis Hill.

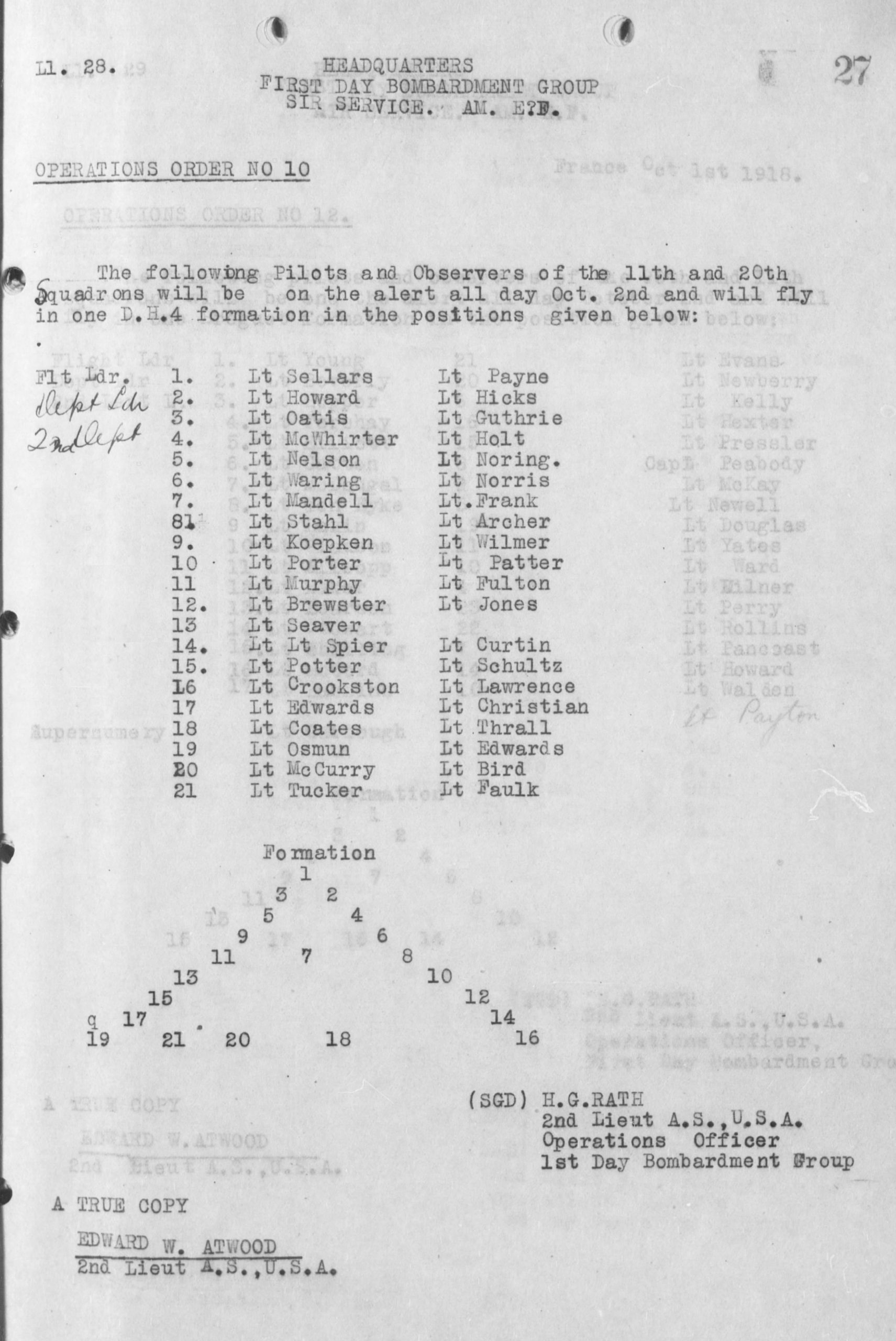

The 11th Aero—one of three squadrons in the 1st Day Bombardment Group (the 166th was later added to the 11th, 20th, and 96th)—had suffered heavy losses during and immediately after the St. Mihiel Offensive, and Heater, arriving to take command on September 21, 1918, found a decimated and demoralized squadron. Heater had extensive experience flying DH.4s with No. 55 Squadron R.A.F.; he lectured the pilots of the 11th now under his command “on the primary importance of close, tight formations” and expressed his confidence in the DH-4. 31 Meanwhile, consultation among squadron leaders and higher-ups in the aftermath of St. Mihiel led to the decision that the 1st Day Bombardment Group planes should fly in larger—more effective and safer—formations. Thus one finds missions during the Meuse–Argonne Offensive made up of formations of as many as forty planes, combining flights from different squadrons.

Helping to bring the squadron back up to strength after St. Mihiel, three second Oxford detachment members in addition to McCurry and Heater joined it: Dana Edmund Coates, Ralf Andrews Crookston, and George Dana Spear. Paul Vincent Oatis, Robert Brewster Porter, Fred Trufant Shoemaker, and Walter Andrew Stahl, all of the second Oxford detachment, had been assigned to the 11th before the offensive (Shoemaker had been shot down and taken prisoner on September 14, 1918). There were also many second Oxford men with the other 1st Day Bombardment Group squadrons, and McCurry later remarked, without exaggerating too much, that “A great many of the boys I trained with, practically all of them that are left, are with us.”32

Shortly before the opening of the Meuse-Argonne Offensive on September 26, 1918, the 1st Day Bombardment Group relocated from Amanty to Maulan, about twenty miles to the northwest and thus closer to the Argonne Forest, and it was at Maulan that McCurry joined the 11th Aero on September 25, 1918.33

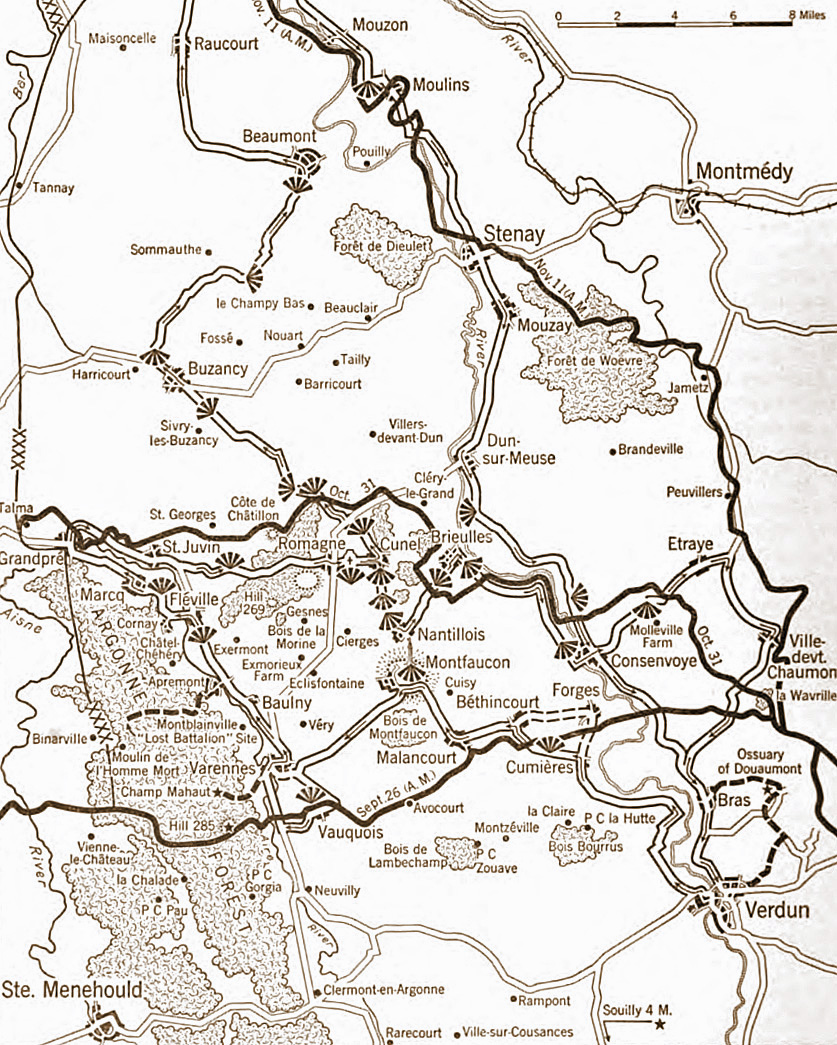

Orders issued on September 23, 1918, ordered the 1st Day Bombardment Group to “attack enemy concentrations along the valley of the Meuse—Romagne—St. Juvin—and Grandpre,” i.e., along an approximately eighteen mile line running from the American First Army’s eastern boundary with the French XVII Corps at the Meuse, to its western boundary with the French Fourth Army at the western edge of the Argonne Forest, all of this about ten miles north of the American front line at the opening of the offensive—and approximately fifty miles north of the aerodrome at Maulan.34

Perhaps because of his late arrival (Coates, Crookston, and Spear arrived September 20, 1918,35 the day before Heater) or perhaps because of lingering medical issues, McCurry apparently did not fly during the opening days of the Meuse-Argonne Offensive.36 His first flight over the lines apparently occurred on October 2, 1918, when, with observer Morton Forrest Bird, he flew at the rear of a large formation made up of DH-4s of the 11th and 20th Aero Squadrons. They left the ground at 9:40 a.m., twenty-five minutes after another large formation of planes from the 11th and 96th had set out as part of the same mission.37 The primary objective was St. Juvin, which fourteen planes of the twenty-two in McCurry’s formation, flying at about 16,000 feet, reached and bombed; the planes arrived back at the aerodrome about two and a half hours after they set off.38

McCurry’s name does not appear in operations reports for the missions flown by the 11th Aero on October 3, 4, and 5, 1918, although according to operations orders, he was to be ready to fly with Bird as his observer on October 3 and 4, 1918.39 Beginning on October 6, 1918, he is recorded as flying every day, except one, that the 11th was active. On at least two days, October 10 and November 3, 1918, he flew twice.40

On October 6, 1918, with observer John Augustus Richards, McCurry flew in the second of that day’s two missions.41 Squadron members recalled that on this day “a new style of raid was undertaken and successfully carried out against the town of Doulcon. Instead of seeking higher altitudes, where most of our work had previously been accomplished, the raid was made and the town bombed from an altitude of only 4,000 feet.” Although this theoretically brought the planes in range of ground fire, the German guns were silent. “Everyone was delighted with the tight formation. . . . This raid did as much to improve the morale of everyone in the outfit as any single occurrence could have done, and it showed everyone the possibility of going directly through the enemy fire at a ridiculously low altitude, making the raid and getting away before any Huns could interfere.”42 Nevertheless, in later missions the 11th generally returned to flying at higher altitudes.

In a letter dated October 14, 1918, McCurry wrote that “About a week ago I got a tire blown off and when I landed the wheels of the undercarriage gave way and had a h—l of a crash. Neither one of us was hurt except bruised and as we were short of pilots went on a second raid that day.”43 The wording suggests that McCurry flew two missions on about October 6, 1918, but this would mean he was among the men of the 11th loaned to the 96th Aero to fly one of their Breguet missions. There is no record in the First Day Bombardment Group’s operations reports of McCurry taking part in a Breguet formation. It seems more likely that his “h—l of a crash” occurred during a practice flight, although how a tire would have been “blown off” remains to be explained.44

The 11th Aero flew no missions on October 7 or 8, 1918. On October 9, 1918, McCurry flew a late afternoon mission with observer William Love Parish, who would continue to be his teammate for the remainder of the war.45 The 11th’s target, Bantheville was a few miles to the west of Damvillers; six planes from the 11th Aero reached their objective, while four, including McCurry’s, did not.46 The available reports seldom give reasons for planes of the 11th Aero not reaching their targets, but the most likely cause—based on the records of other DH-4 squadrons—would have been engine problems.

Two missions were flown on October 10, 1918, one in the early morning and the other around noon. Both combined pilots and planes from the 96th, 20th, and 11th Aero Squadrons for a total of forty and thirty-nine planes respectively. McCurry with Parish successfully flew both missions, releasing bombs over Milly-devant-Dun and later over Villers-devant-Dun; both objectives were somewhat farther north and farther east than the previous targets, reflecting the American advance.47

In the letter of October 14, 1918, cited above, McCurry describes how “Three days ago I got in a scrap with some Fokkers. At 14,000 feet had my tail plane partly shot away and a couple of bullets went through my machine about a couple of feet from me. My observer (machine gunner) in the rear seat . . . shot down the Hun who was making things hot for us.” I find no record of this incident in the relevant operations reports of the 1st Day Bombardment Group or in the raid reports of the 11th Aero. However, the 20th Aero’s raid report for the noon mission on October 10, 1918, recounts how “As formation approached Aincreville going towards Villers devant Dun at 12:20 Oct. 10, 1918 Fokkers with Black Fuselages Red noses, Light [illegible] attacked aggressively from the rear. The fight lasted about 15 mins. During which time the formation bombed Villers and made a left hand turn for the lines[.] Our observers fired 1500 rounds of ammunition. One enemy plane was seen to fall in flames and another fall out of control both in the region of [V]illers at 12:25 p.m.”48 It is possible that McCurry and Parish were among those involved in this combat, possibly having gotten separated from the planes of the 11th and attaching themselves to those of the 20th Aero.

Unfavorable weather meant that from October 11 through October 22, 1918, only one mission, on October 18, 1918, was flown, and McCurry did not fly that day, but he and Parish participated in both of the missions flown on October 23, 1918. The primary objective of the morning mission, which combined teams from the 11th and the 20th, was Buzancy; a number of the teams, McCurry and Parish included, were not able to reach the target town north of St. Juvin.49 In the early afternoon, a total of forty-eight planes from the 1st Day Bombardment Group—which now included the 166th Aero Squadron—set out for the Bois de Barricourt; again a number of teams, including McCurry and Parish, were unable to reach the objective. During both of these missions enemy planes were encountered and engaged.50

Bad weather once again meant that only test flights were flown until October 27, 1918, when another large formation combining planes from the four squadrons took off in the early afternoon for Briquenay. McCurry and Parish, flying plane no. 20, were among the teams able to reach the target, which was nearly fifty-five miles north of the aerodrome at Maulan.51 “The objective bombed from the altitude of 11,000 feet. Bursts being observed on edge of town. Twelve enemy planes were encountered at 15:10 o’clock in the vicinity of the objective, and one enemy plane was seen to go down out of control. All our machines returned safely at 16:00 o’clock.”52

Where plane numbers are provided in accounts of McCurry’s remaining missions, he continues to fly plane no. 20. He and Parish continued, like most of the pilots, to have mixed success in completing missions. They flew twice on November 3, 1918; in the morning they appear not to have reached Stenay and Martincourt-sur-Meuse, but were among the teams who reached and targeted Beaumont-en-Argonne at three in the afternoon.53 Ten minutes later the flight was attacked by eight Fokkers, and “a running fight ensued, in which two of the enemy planes were driven out [sic] of control.”54

Planes from the 11th Aero crossed the lines for the last time on November 4, 1918 (a mission the next day set out but was called on account of cloud cover). The mission on the 4th was again composed of a large number of planes from the four squadrons; the objective was Montmédy, nearly as far north as Beaumont. A number of teams, including McCurry and Parish, were unable to reach the target.55 The formation’s return flight was made difficult by a strong head wind—McCurry in a letter dated November 5, 1918, noted that “Coming back yesterday I was bucking a 60-mile [wind] at 10,000 feet.”56 German planes attacked the main formation, and two planes were downed and their crews killed, including McCurry’s fellow second-Oxford detachment member Coates.

Passages in McCurry’s letter of November 5, 1918, indicate that flying and late autumn weather were taking their toll: “Am a long way from the good old U.S.A., and the going is getting tougher all the time—raid, raid, raid, and no rest even when it is pouring rain. . . . Don’t know when peace is coming since every one but Germany is out, but I hope it isn’t far away. I am fed up to the gills and wish I could have stayed with the English. All leaves were called off just as I was about due for mine.” Three days after the armistice, he continued the letter: “November 14. Since I wrote the above I have had too much of a grouch to finish it until I found it in my pocket today. Am still fed up, but peace covers a multitude of sins and I suppose we are all glad. A lot of us are being recommended for promotions now that it is over. Personally I don’t care if they make me a general, I want to get out as quick as I can get out. . . . There was nothing to do [to celebrate the armistice] where we are but to get a lot of champagne, which we did, and shoot off about half the bombs, rockets and flares we had for which we were all put under arrest, but released a couple of days later.”57

McCurry’s wish to “get out as quick as I can” was granted. While many soldiers and pilots had a long wait for transport home, he was able to sail to New York from Brest on January 5, 1919, on the President Grant. 58 He returned initially to Washington, but then moved to southern California and settled in Los Angeles where he worked as a securities broker.59

mrsmcq March 27, 2020

Notes

(For complete bibliographic entries, please consult the list of works and web pages cited.)

1 McCurry’s place and date of birth are taken from Ancestry.com, U.S., World War II Draft Registration Cards, 1942, record for Uel Thomas McCurry.. His place and date of death are taken from Ancestry.com, California, Death Index, 1940–1997, record for Uel Thomas McCurry. The photo is taken from a 1917 newspaper article, “M’Curry is Sent to Italy to Help Down the Kaiser.”

2 Information on McCurry’s family is taken from documents available at Ancestry.com.

3 “News of the Churches.”

4 The family’s movement are somewhat uncertain, but see the obituary for Grace McCurry from the Rogers Democrat of September 26, 1901, reproduced at “City of Rogers Cemetery Database.”

5 “Leaders in Sports at Blair.”

6 “Chapter Letters,” p. 479; University of Idaho, Bulletin 4.1: 207 and Bulletin 5.3: 239.

7 “M’Curry to Head New Tennis Club.”

8 See, for example, “Late News from the World’s Mining Camps,” p. 561; “Mining Notes” (January 28, 1917).

9 “Spokane Company Lands French Ship Contract.”

10 “Mining Notes” (June 1, 1917); “Herbert Irvine, Mining Broker, Taken by Death.”

11 “Ground School Graduations [for August 25, 1917],” “Ground School Graduations [for September 1, 1917].”

12 The photo is used in Robert Clem’s film War Birds. I am still in the process of locating the original photo.

13 “Letters from Spokane Boys.”

14 See Foss’s list of “Cadets of Italian Detachment Posted Dec 3rd” in Foss, Papers.

15 The National Archives (United Kingdom), Royal Air Force officers’ service records 1918–1919, records for McCarthy, McCurry, Nial (where for 196 read 198), and Young. On 198 T.S., see Stedman, “Night Fighter Pilot,” pp. 37 and 46.

16 “Air Training in England Exciting.” On the December 6, 1917, raid, see the entry for that date at Castle, Zeppelin Raids, Gothas and ‘Giants’: Britain’s First Blitz – 1914 – 1918.

17 “Learns to Fly in England.”

18 Cablegrams 612-S and 852-R.

19 Harbord, “Special Orders No. 79.” (McAndrew, “Special Orders No. 205,” indicates that McCurry was placed on active duty on March 28, 1918.)

20 On the aircraft at Boscombe Down, see Sturtivant, Hamlin, and Halley, Royal Air Force Flying Training and Support Units, p. 294.

21 Quotation from “Ambulances Eye Young Aviators.” Bruce, The de Havilland D.H.4, p. 8, and Sturtivant and Page, The D.H.4 / D.H.9 File, p. 17, give a maximum speed of 136.5 at 6,5000 feet. Mason, The British Bomber since 1914, p. 68, records that, with a Rolls Royce 375 hp Eagle VIII engine, the DH.4 could achieve a speed of 143 m.p.h. at sea level.

22 See the casualty list on p. 5 of Dwyer, “Report on Air Service Flying Training Department in England.”

23 See The National Archives (United Kingdom), Royal Air Force officers’ service records 1918–1919, record for U T McCurry.

24 [Biddle?], “Special Orders No. 109”; this is dated June 5, 1918, but the correct date is almost certainly July 5, 1918.

25 “8th Aero Squadron,” p. 140.

26 See “8th Aero Squadron,” p. 134.

27 See the brief “History of Eighth Aero Squadron (Observation)” on pp. 110–12 of “8th Aero squadron.

28 8th Aero Squadron,” p. 116; this is part of the “Report on Operations against the St. Mihiel Salient” submitted by Winant, which is also reproduced on pp. 689-91 of Maurer, The U.S. Air Service in World War I, vol. 3.

29 “Spokane Man and Hun Fight in Air.”

30 “8th Aero Squadron,” p. 142.

30a “11th Squadron,” p. 4.

31 Heater, quoted in Skinner, “Commanding the 11th,” p. 264.

32 “Ex-Spokane Flyer Believed Dead.”

33 “11th Squadron,” p. 4.

34 Maurer, vol. 2, 242.

35 “11th Squadron,” pp. 4–5.

36 I use “apparently” here and elsewhere because the available documentation may not be complete or completely accurate.

37 Rath, “First Day Bombardment Group, Account of Operations, pp. 116–17.

38 Ibid., and “11th Squadron,” p. 73. Here and else where the accounts provided by the two sets of records differ in some details. NB: The raid report on p. 73 of “11th Squadron” records a flight altitude of “4700”; comparison with other reports and with the account on p. 165 of History of the 11th Aero Squadron U.S.A. (see below) indicate that the unit of measurement was meters. See also Norris, [History of operations of the 11th Squadron during St. Mihiel Offensive], p. 55.

39 “11th Squadron,” pp. 29 and 31.

40 Rath, “First Day Bombardment Group, Account of Operations,” passim.

41 Rath, “First Day Bombardment Group, Account of Operations,” p. 122; “11th Squadron,” p. 77. The former document gives McCurry’s plane number as “18,” but comparison with Coates’s log book entry for that mission suggests that he flew No. 8.

42 History of the 11th Aero Squadron U.S.A., p. 165. The altitude figure (“5,000 feet”) in the entry for this day in Norris, [History of operations of the 11th Squadron during St. Mihiel Offensive], has been changed (incorrectly?) by hand to “5,000 meters.”

43 “Spokane Man and Hun Fight in Air.”

44 Rath, “Summary of Operations of First Day Bombardment Group,” passim. It is also possible that McCurry was recalling his two missions on October 10, 1918, although the wording and context in the letter argue against this, and the operations report (Rath “Summary,” p. 125) does not mention a crash. On pilots of the 11th and 20th Aero being loaned to the 96th to fly Breguets, see Guttman, “Slaughter in the Sky,” p. 34, and Richardson, “The Wartime Diary of Clifford Allsopp—Bomber Pilot,” p. 58.

45 Although not apparent from the account in Howard G. Rath’s “First Day Bombardment Group, Account of Operations” or in “11th Squadron,” which does not record the mission, this was the day of what was later described as “The most remarkable concentration of air forces during this offensive . . . something over 200 bombing airplanes, and about 100 pursuit airplanes, and 53 triplace machines, after rendezvousing in our rear area, passed over the enemy lines in two échelons. A total of 32 tons of bombs were dropped on the cantonment district between La Wavrille and Damvillers. . . .”(Maurer, The U.S. Air Service in World War I, vol. 1, p. 44; for a critical account of this operation, see Lengel, To Conquer Hell, pp. 314–15). It is not clear to me whether the 11th Aero’s activities were coordinated with or part of this “remarkable concentration.”

46 Rath, “Summary of Operations of First Day Bombardment Group,” p. 124.

47 On these missions see Norris, [History of operations of the 11th Squadron during St. Mihiel Offensive], p. 56; Rath, “Summary of Operations of First Day Bombardment Group,” pp. 125–27, and “11th Squadron,” pp. 78– 79. Milly-devant-Dun is now Milly-sur-Bradon.

48 Sellers, “History of the 20th Aero Squadron Air Service, U.S.A.,” p. 230.

49 Rath, “Summary of Operations of First Day Bombardment Group,” p. 131.

50 Ibid., pp. 132–33.

51 Rath, “Summary of Operations of First Day Bombardment Group,” pp. 134–35.

52 Norris, [History of operations of the 11th Squadron during St. Mihiel Offensive], p. 56.

53 Rath, “Summary of Operations of First Day Bombardment Group,” pp. 145–47.

54 Norris, [History of operations of the 11th Squadron during St. Mihiel Offensive], p. 57.

55 Rath, “Summary of Operations of First Day Bombardment Group,” p. 148.

56 History of the 11th Aero Squadron U.S.A.,” p. 175; “Ex-Spokane Flier Believed Dead.”

57 “Ex-Spokane Flier Believed Dead.”

58 War Department, Office of the Quartermaster General, Army Transport Service, Lists of Incoming Passengers, 1917 – 1938, passenger list of officers, casual, on U.S.S. President Grant, sailing from Brest January 4, 1919,

59 Ancestry.com, 1930 United States Federal Census, record for Uel McCurry.