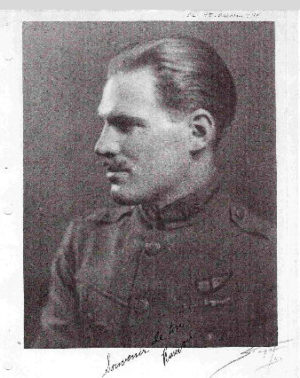

(Toledo, Ohio, September 18, 1892 – New York City, February 9, 1952)1

Oxford & Grantham ✯ Waddington ✯ Marske, Stonehenge ✯ France ✯ 11th Aero, St. Mihiel ✯ September 18, 1918, and after ✯ Meuse-Argonne ✯ Afterwards

Oatis was of Irish descent. His father, who worked for the Toledo and Ohio Central Railway, married Mary Catherine Ryan in 1890. She died in 1899, leaving Peter Oatis to raise their two sons. Census records show the boys living for a time with their maternal grandmother and then with their father in lodgings in Toledo.2 Oatis attended St. John’s University in Toledo and presumably graduated in 1913 or 1914; at some point he was a reporter for the Toledo News-Bee.3 He evidently had an interest in and flair for the bond market; he began working for Sidney Spitzer & Co., a Toledo investment bank, when he was in his early twenties and returned to investment banking after the war.4

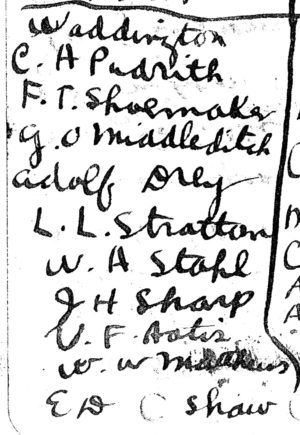

Oatis’s draft registration shows that in June 1917 he was in R.O.T.C. at Fort Sheridan in Illinois. Not long after he began his R.O.T.C. training, men were asked to apply for the Aviation Section of the Signal Corps. Oatis was initially skeptical about his chances, but gave it a try. On June 27, 1917, he learned, to his surprise, that he had passed the rigorous exams and would be transferred to aviation.5 By mid-July he, along with a number of other men from Fort Sheridan, was at ground school at the School of Military Aeronautics at the University of Illinois; their class graduated from ground school on September 1, 1917.6 A photo kept by Joseph Raymond Payden suggests that Oatis was close to classmates George Orrin Middleditch and Chester Albert Pudrith, both of whom had also been at Fort Sheridan. Walter Andrew (“Jake”) Stahl, who would share training and operational assignments with Oatis in England and France, was also at Fort Sheridan and in Oatis’s ground school class.

There was much speculation about where graduates from this ground school class would go for actual flying training, with information and plans changing frequently—Oatis’s first of many lessons in the uncertainties of military life. The initial understanding was that the men would “go to Rantoul to the aviation field and pursue the actual flying game from three to four months.”7 In mid August, however, there was a request for volunteers “who would like to go to Italy for their air training. Right now Italy is about the best in the world in flying, so I grabbed at it and applied. Nearly everyone in our squadron did likewise.”8 Shortly after ground school graduation, however, the students were divided into two groups, one to go to Mineola on Long Island and thence to Italy, and the other, which included Oatis, to go to Fort Wood on Bedloe Island in New York Harbor to be outfitted for France.9 Oatis had just been made a drill sergeant at Fort Wood when, on September 12, 1917, a request came for a number of the men at Fort Wood to join the men at Mineola going to Italy. As a result all but five of Oatis’s ground school class of thirty were reunited and “bound for some flying school in sunny Italy.”10

Altogether there were 150 men in the detachment that was supposed to train in Italy; they sailed from New York on September 18, 1917, on the Carmania. The ship made a short stop at Halifax and there joined a convoy for the Atlantic crossing, setting out September 21, 1917. The men of the detachment travelled first class and had plenty of leisure: “We doze and sleep and eat and have tea and drill and study Italian etc. in a most perfunctory way.”11 Italian lessons were conducted by Fiorello La Guardia, assisted by violinist Albert Spalding. Towards the end of the voyage, as the convoy entered particularly dangerous waters, the men were assigned to submarine watch duty which was, fortunately, uneventful.

Oxford and Grantham

When the Carmania docked at Liverpool on October 2, 1917, there was another change of plans: the men were not to go on to Italy but to remain in England and, even worse, as it seemed, to go through ground school all over again. They travelled by rail to Oxford and Oxford University where the Royal Flying Corps’s No. 2 School of Military Aeronautics was located. The “Italian detachment” became the “second Oxford detachment”—a first detachment of fifty American pilots in training having arrived there a month earlier. At Oxford the men spent their first night scattered among the various colleges; the next day they were divided into two groups. Ninety men were assigned to Christ Church college and sixty, including Oatis, to The Queen’s College, where they would remain for just over two weeks. At that point, in the aftermath of some high spirited and bibulous celebrations, the British insisted on moving all the Americans into a single college, Exeter.12

The men made the best of their second round of ground school. Oatis was not alone in appreciating the instructors “being right in touch with the very latest developments at the front,” many of them having “had personal experience and are therefore better able to tell us the things we must know. We had a good many things taught to us at home that they don’t teach here, so that the combination of the two courses will really be worth a great deal more than either course, alone.”13 Nevertheless, “Classrooms and books get to be an awful bore after a certain length of time.”14 It was thus encouraging when, after about three weeks, “Unofficial information is that 100 of our crowd will be posted to a flying school next Monday.”15

In fact, because there were so few openings, only twenty of the men of the second Oxford detachment went straight from Oxford to a flying school; the others, including Oatis, travelled on November 3, 1917, to Grantham in Lincolnshire to attend the machine gunnery school at Camp Harrowby. There they spent two weeks learning about and practicing with the Vickers machine gun. Then, in mid-November, it was determined that there was room at training squadrons for fifty of the Grantham cadets.

Waddington

On November 19, 1917, the fifty men set out for various R.F.C. stations. Oatis, along with Middleditch, Pudrith, Stahl, and five others, was sent to Waddington, just south of Lincoln and about twenty miles north of Grantham; several R.F.C. training squadrons were located there.16

Oatis did not do any flying during his first two weeks at Waddington—perhaps because he and his fellow cadets were being given yet more ground instruction, or perhaps because of poor weather or a lack of planes. There was a bright spot during this period, however, when Oatis and many of the others who had been assigned to training squadrons went back to Grantham to join the men still there in the Thanksgiving celebrations that had been in the planning for some time.17

In his first letter home from Waddington, dated December 11, 1917 (and continued on subsequent days), Oatis is delighted finally to be flying: “It has taken a long long time to do it but we have finally killed the jinx. Last Tuesday we started flying and most of us are already soloing.” Oatis’s log book shows that late in the morning of December 4, 1917, he put in twenty-five minutes of dual flying in DH.6 [A]9660 with instructor Harold Claude Millerd Orpen of 75 Training Squadron at Waddington.18 In the afternoon he flew for forty minutes with Graham Campbell Body of 48 T.S. at Waddington.19 Oatis continued at No. 48 T.S. through the end of March 1918.

Oatis provides a lengthy account of R.F.C. training in his December 11, 1917, letter, noting that “When you show your instructor that you have a working knowledge of how to take off and get back to earth without killing yourself, they let you go up solo.” He made his first solo flight on December 10, 1917 in DH.6 [A]9696. He provides a brief description of this plane for his father: “We are using a bus for training that is [as] nearly [fool] proof as it can be made. It is built solely for training and of course is not at all like the real service machines. It only does about 50 or 60 m.p.h. on the level, and you can land them at about 30 miles per hour. They are something like the Curtiss used in the states except that they use stick control instead of the wheel.” Later in the same letter Oatis notes that after elementary training, students might be selected to continue training on fighter scouts. An informal survey suggests that this is what most of the second Oxford detachment men hoped to do; the idea of flying a fast single-seater plane in combat against enemy aircraft possessed considerable glamor. It is thus an agreeable surprise to find that Oatis was already attracted to the kind of work he would eventually do: “But the chaps who accomplish the work of greatest immediate military importance, are the fellows who fly the observation, photographic, bombing and similar machines.”20

On December 15, 1917, Oatis experienced his first crash. On his third and longest flight that day, he got lost and landed badly at Metheringham, a few miles east-southeast of Waddington, and busted the propeller of DH.6 [A]9660. Nevertheless, there was something to celebrate: he had soloed for five hours and had made fifteen landings, which meant he could move on to other types of planes.21 It also meant a reward of four days leave, which he originally intended to use to go with friends to London—but he later notes that he saw London for the first time just before Easter, so he evidently spent his leave elsewhere or did not take it after all.22

When Oatis resumed flying on December 22, 1917, he went up for the first time in an R.E.8 ([A]3558) as pilot Roland Godefroy Hornby’s passenger.23 On the last day of the year Oatis went up in an R.E.8 with Body, this time flying dual and receiving instruction on flying a straight course and making turns; he went through the same process in a B.E.2e in January, all the while continuing to fly DH.6s solo, practicing various maneuvers.

Oatis’s first letter home in the new year opened with bad new, the death in an air crash on January 7 of Joseph Hiserodt (“Joe”) Sharpe, who had trained alongside Oatis since their ground school dates at Champaign. Oatis served as one of the pall bearers at Sharpe’s funeral at Lincoln on January 11, 1918.24

After telling him about Sharpe, Oatis sought to reassure his father by recounting how he himself had come out of two crashes unscathed. In addition to his mishap on December 15, 1918, he had been a passenger in R.E.8 [A]4507 piloted by a Lieutenant Jones on January 12, 1918. Jones had asked Oatis “how I’d like to climb” and took him up to 9,000 feet. Emerging from thick clouds as they descended, they realized they were lost, but Jones managed to land in a field near Wragby, some twelve miles northeast of Waddington. All would have been well but that the wheels caught in the wet ground, and the plane turned over. The plane was damaged, but pilot and passenger were fine.

By the time he finished his letter of January 14, 1918, Oatis had flown for fifteen minutes as a passenger in a DH.4 piloted by Body; he already anticipates flying this type of plane in France and is enthusiastic about it.25 He complains in the same letter that bad weather and crashes have “slowed up our flying considerably,” but soon he started piling on the hours. On February 12, 1918, he passed another milestone: twenty hours of solo flying, one of the requirements for graduating from this stage of R.F.C. training, as well as for earning a commission. Oatis closes a letter begun February 9, 1918, and evidently continued on February 12, 1918, with the remark: “Have finished 20 hours and have been recommended for commission.” And, indeed, the recommendation was evidently forwarded to Pershing, who, with military speed, included Oatis’s name in a list of men recommended “as First Lieutenants Aviation Reserve” in a cable to Washington dated February 26, 1918; the confirming cable came back dated March 11, 1918.26

Just after completing his twenty hours solo, Oatis got quite a scare. His propeller stopped while he was on the ground, and he started it himself with no one in the cockpit. But he had left the throttle “too wide open and there was no one in the bus to cut her out.” The plane, DH.6 [A]9662, took off over the hangars before the engine torque caused it to turn, dive, and crash. The plane was a write off, but, fortunately, caused no other damage to people or property. Oatis learned a lesson about not swinging a prop without someone at the throttle and came in for a good deal of teasing about his pilotless plane.27

Three days later, on February 15, 1918, Oatis had his first ride in an Armstrong Whitworth FK.8 (B9600). His pilot, Captain Brooke, showed him loops, Immelmanns, stalls, and spins—not maneuvers that could be done in DH.6s.28 Oatis was enthusiastic about learning to stunt, not so much for the thrills, but rather because practicing taught “you how to get into difficulties and then how to get out of them.”29 Over the course of March 1918, Oatis flew dual in an A.W. FK.8 (which he called a “small Armstrong Whitworth”) five more times, mainly to work on stunting.

Going back to the preceding month: On February 17, 1918, Oatis passed another requirement for R.F.C. graduation: the “height test”—flying at 8,000 feet for fifteen minutes. Yet another R.F.C. graduation requirement was a cross-country flight of at least sixty miles with two landings. There is no entry marked as such in Oatis’s log book, but it may be that he fulfilled this requirement on February 27 and 28, 1917. He and three other pilots (Sydney Moxey, the otherwise unidentified MacKay, and an unnamed third) set out from Waddington the morning of the twenty-seventh and landed in Narborough, about fifty miles to the southwest. The next leg of the trip was supposed to take them about sixty miles east to Tydd St. Mary, but Oatis’s companions had engine trouble and they all put down in a long, narrow field about six miles to the east at Terrington St. Clement in marshy fen country. Help was obtained at Tydd St. Mary, but the men ended up staying overnight. The next day they flew back to Waddington with a stop at Harlaxton near Grantham.30

During the first three weeks of March, Oatis put in many hours of dual and solo flying, practicing evasive maneuvers, aerial fighting, photography, bomb dropping, formation flying, and landings and forced landings, much of the time now in B.E.2e’s. He passed the final requirement for graduation on March 24, 1918. Having flown dual for forty minutes with instructor Alfred Gordon Tooth in R.E.8 [A]4507, he went up solo in R.E.8 [A]3438 for fifteen minutes to make his “graduation flight” on a service plane.31 He made two more flights at No. 48 T.S., and at the end of the day and his time there, on March 25, 1918, he had put in sixty-three hours of flying time, slightly over two thirds of it solo. The next day he was put on active duty—something that normally happened a considerable time after graduation from this stage of R.F.C. training, but which in Oatis’s case, with his commission recommendation having been passed on so early, was unusually timely.32 R.F.C. graduation also meant another four days of leave, and he was now finally able to visit London. As it happened this occurred during Holy Week (Easter was on March 31, 1918), so many of the sights he would have liked to have seen were closed.33

Given that he wrote his father about the death of Sharpe in his January 14, 1918, letter, one might anticipate that Oatis would also mention the accident that occurred at Waddington on March 12, 1918, involving his friends Middleditch, who was killed, and Pudrith, who was seriously injured—but this is not the case. Instead, Oatis, like many of the other men in the detachment in their letters home, seemed intent on reassuring his family and avoided passing on grim news. That Oatis kept up with Pudrith is apparent from a March 19, 1918, entry in William Ludwig Deetjen’s diary: “Went down with [instructor Arthur Harold] Beach, Shuey [Fred Trufant Shoemaker], Oatis and Jake Stahl and ran up to the Northern Hospital to see Chick Pudrith.” Pudrith died at 4th Northern General Hospital in Lincoln at the end of April; Oatis may well have been a pall bearer at both his and Middleditch’s funerals. Not until he had left Waddington did Oatis allude to these deaths. His father appears to have come across excerpts from a letter, apparently from Oatis to fellow Toledoan Claude Edward Vollmayer, that had appeared in the Toledo News-Bee.34 In a letter written May 18, 1918, Oatis reacted to “the News Bee clipping about Volly and me”: “I never dreamed that letter would get to your eyes. It was terribly misquoted, but I wouldn’t have let you know about any of those accidents. I can speak frankly about it now, because I finished my training, and the likelihood [of] accidents is about 100% reduced. Our little crowd, especially my closest friends had rotten luck and I was tickled to get away from Lincoln. I had attended too many funerals there.”

After his graduation leave in London, Oatis returned to Waddington, where he was now assigned to an advanced training squadron, No. 44 T.S. On his initial flight there, on April 4, 1918, he went up in a DH.4 ([A]7736), flying dual with instructor Stratton. Three days later he went up for the first time in a DH.9 ([C]6077), now with Beach, who would continue to be Oatis’s instructor for much of his remaining time at Waddington.

Oatis’s experiences of the night of April 12–13, 1918, were worth writing home about—with due care for censorship—as Waddington was targeted that night during the last German Zeppelin raid on Britain. Oatis and fellow second Oxford detachment member James Mitchell Coburn were preparing for sleep when they heard a rumble and an explosion; they scrambled into clothes and went outside to listen and watch. They, and Waddington, were fortunate. As a relieved Oatis concluded, “the safest place to be is the place they are aiming for,” besides which, the bombs that fell nearest them failed to explode.35

On April 21, 1918, Oatis went up solo for the first time at No. 44, in DH.9 [C]6188, and he flew solo during most of the remainder of his time at Waddington. Twice he took up a Martinsyde ([A]6278), but otherwise flew DH.9s. Towards the end of April 1918 he passed his second height test, which required him to fly up to 17,000 feet.36

Also towards the end of April, Oatis was saddled with duties he had not anticipated. His roommate, Stahl, “was in command of flying officers and cadets at the station. He dislocated his hip, and the job was wished on me.”37 As a result, Oatis was glad when his Waddington training was over and he was sent to the No. 2 School of Aerial Fighting and Gunnery at Marske-by-the-Sea in north Yorkshire—although less pleased when there was a long gap in his flying and no news about when he would go overseas.

Marske, Stonehenge

When he did finally begin flying at Marske on May 23, 1918, Oatis was in an Avro for the first time, flying dual and being tested by instructor William Buckingham.38 Oatis flew again five days later, this time in a DH.9 piloted by “Landon”—probably his fellow second Oxford detachment member Edward Carter Braxton Landon; during this flight Oatis “Acted as observer in aerial fight.” It appears that yet another detachment member, Glenn Dickenson Wicks, was Oatis’s passenger in a DH.4 on June 1, 1918, when he was “Fighting vs. Capt. Maddox” (Henry Hollingdrake Maddocks).39 A few days later Oatis once again served as an observer, this time for “Cronin”—probably detachment member Edward Matthew Cronin—who was flying a DH.4 in an aerial fighting test.

Oatis flew in a Bristol Fighter, for the first and only time, as a passenger with pilot Buckingham on June 6, 1918, and finished out his time at Marske practicing fighting and formation flying in DH.9s. On his last flight there, on June 11, 1918, he took part in a “fighting test” against “Maj Aizelwood” (Leslie Peech Aizlewood).40

Oatis still had one more stage of training in what at times seemed an interminable process. Despite his impatience to get to France, he found the course at the No. 1 School of Navigation and Bomb Dropping at Stonehenge, where he was posted in mid-June 1918, invaluable: “Aside from flying itself, this navigation course is the most useful thing I’ve seen.”41 The course “consisted of learning to fly by instruments, to fly not only through, but in clouds. That may sound easy but it’s the hardest thing I’ve ever done since I started this game.”42 His initial flying test at Stonehenge was in a DH.9, after which he was back flying B.E.2e’s for a time, practicing formation flying, passing a cross-country navigation test, practicing live bomb dropping, and working on “cloud flying.”

On June 29, 1918, Oatis was once again in a DH.9, and on that day passed a test of his ability to fly cross country above clouds. Two days later, he flew “head in bag.” This phrase can refer to a specific test at the No. 1 S. N. & B. D., designed to determine whether the pilot could fly a straight course relying on instruments only. “Pilot’s head to be enclosed for not less than 9 minutes on each course. Observer to hand in a fair copy of graph showing Pilot’s course… Pilot must not deviate more than 15° off his course at any one time.”43 But, if I have correctly matched Oatis’s log book entry with an account in his letters, a pilot also flew “head in bag” when needing to practice cloud flying in the absence of clouds: the observer would shroud the pilot in “a business like an awning of black cloth that completely enclosed the pilot. You can’t see a thing but your instrument board.”44 Had it been a test on the first of July, Oatis would presumably have failed it, having gotten into a spin he could not get out of until his badly frightened observer had removed the black cloth.

There was not another opportunity to practice or be tested, as this turned out to be Oatis’s last flight at Stonehenge. With almost 107 hours of flying time under his belt, almost three quarters of it solo, Oatis was ordered to report to London “About three days before I had actually finished the course” at No. 1 SN & BD.45 He was able to join in the Fourth of July celebrations in London, and was especially pleased to know that quite a number of his friends would be joining him. Orders dated July 5, 1918, however, dampened spirits: rather than going to an R.A.F. squadron as he hoped and expected, Oatis was among a large number of American DH.4 trained pilots told to report to Issoudun in the Loire region of France where the American 3rd Aviation Instruction Center was located.46 Harold Ernest Goettler, who was in this group, noted in his diary leaving London for Southampton on July 7, 1918, and setting out that evening on the Prince George for Le Havre.

France

Arrived at Le Havre on July 8, 1918, the men went to No. 2 Rest Camp to await further instruction.47 Special Orders dated July 9, 1918, reiterated that nearly all of them, including Oatis, were to continue to Issoudun. The thirty-six hour journey in cramped railway carriages was interrupted briefly by a two-hour stop at Orleans. Once arrived at Issoudun—where, according to Goettler, “they did not expect us and had no place to sleep”48—hopes that the group might be “mobilized as an American squadron and go to the front immediately” were dashed; the one bright spot for Oatis was encountering his friend Claude Vollmayer, who was testing planes at Issoudun.49

From the 3rd A.I.C., some of these pilots proceeded to the 2nd A.I.C. at Tours, about seventy miles northwest of Issoudun, for further work at the School of Observation Training, while others, including Oatis and Stahl, were sent to the 7th A.I.C. at Clermont-Ferrand, about ninety miles southeast of Issoudun.50 Oatis wrote two letters to his father during the month of August 1918, in both of which he tried to rein in his profound discouragement at having to continue training rather than being sent to the front. He particularly disliked the French Breguets used at Clermont-Ferrand and was “very much afraid I’ll be going to the front on a French machine. I’m nearly heartbroken over it as I thoroughly dislike it from top to bottom.”51 His log book shows almost daily flights on Breguets starting on July 18, 1918, when he went up with instructor Charles McIlvaine Kinsolving, and continuing through August 31, 1918. On August 26, 1918, however, Oatis got a chance to fly a Liberty DH-4—the American version of the British DH.4: “My trip behind the Liberty motor was sub rosa, or rather unofficial. A chap with whom I trained in England but who worked it to go to the front instead of Stonehenge, is back, and instructing here. We went up for a joyride one morning and I slipped a joystick into the socket and took control up in the air.”52 The “chap” was Frank Simpson Whiting of the first Oxford detachment; he had been with No. 98 Squadron R.A.F. flying DH.9s before going to Clermont-Ferrand as an instructor.53

11th Aero, St. Mihiel

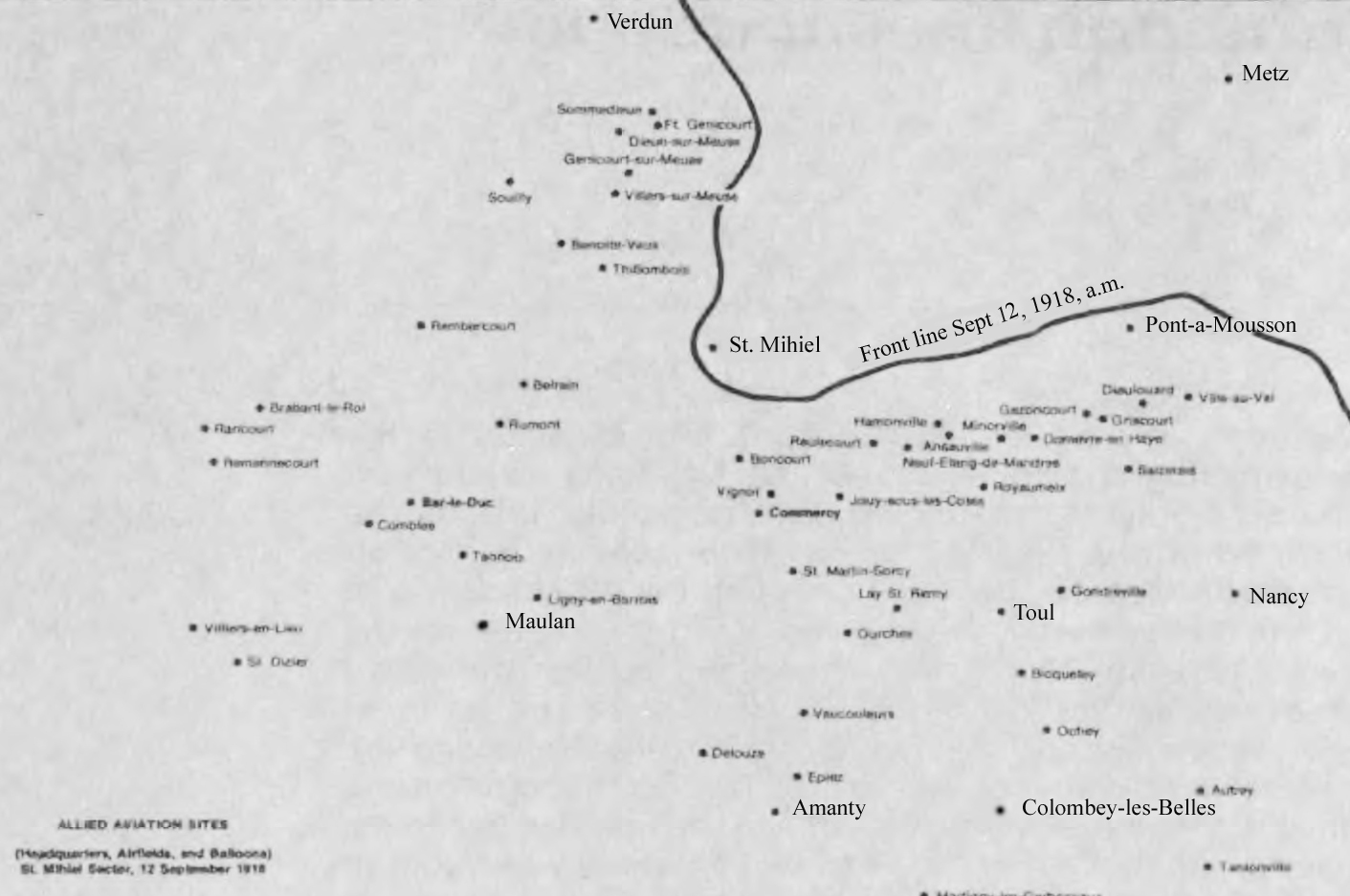

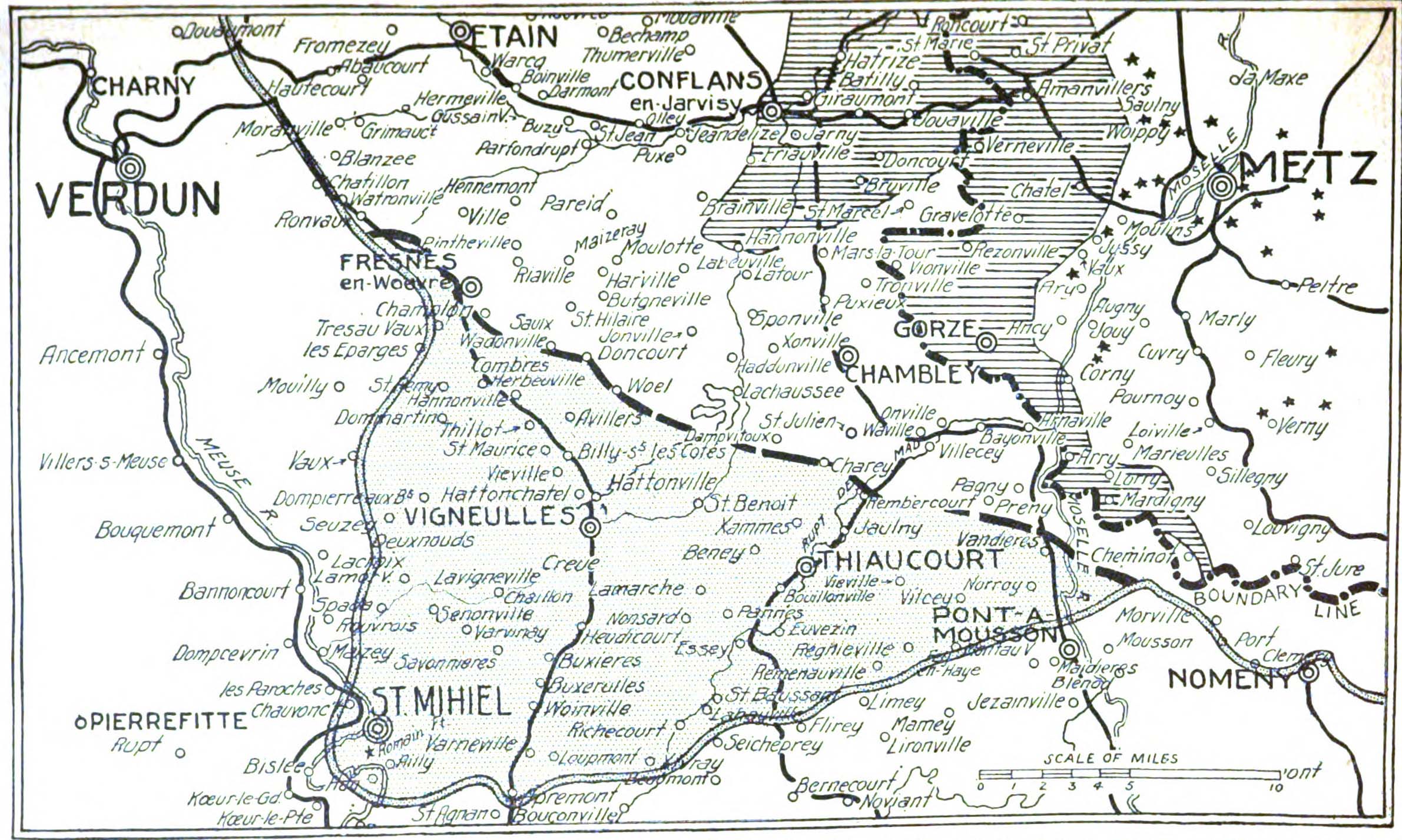

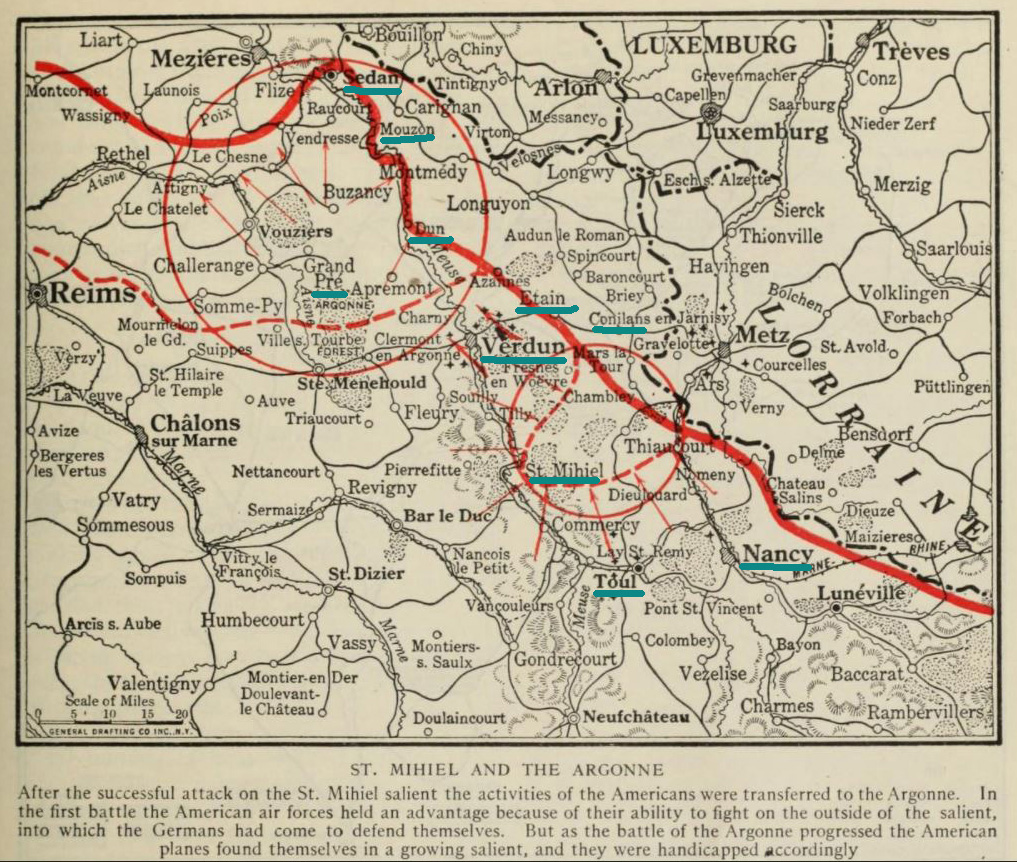

The field at Amanty, about twenty-five miles south of St. Mihiel and the front, was shared by the 11th, the 20th, and the 96th Aero Squadrons, the last-named being the only operational American bombing squadron up to this point. Although instructions for daylight bombing were drawn up in the course of August, it wasn’t until September 10, 1918, that the three squadrons became the First Day Bombardment Group.55 By this time the newly-established American First Army was completing preparations for the St. Mihiel Offensive, in which the First Army, with assistance from the Allies, would seek to wipe out the German held salient that jutted southwest from the Allied line to encompass the town of St. Mihiel on the east bank of the Meuse River. It had been hoped that the attack could begin before the autumn rains, but it was delayed from the 7th until the 12th, and, in any case, the rains came early.56

On the first two days of the St. Mihiel Offensive, September 12 and 13, 1918, pilots of the 11th (and 20th) Aero, whose planes were not yet outfitted for bombing, were tasked with observation and escort duties.57 Oatis’s log book records a fifteen minute flight on September 12, 1918, with observer Guthrie in the direction of Toul—probably bound for Gengoult Aerodrome and escort work—and then a forced landing at Pagny. In a letter dated September 17, 1918, Oatis wrote that “We expected a few days to get all ready and prepared for work, but big things started and we got busy immediately. The first day we started out on some special work, out of our regular line. I got 8 miles from our aerodrome when my motor cut out and I had to land on top of a rocky hill.” Oatis and Guthrie were not hurt, but wind blew their DH-4 over and smashed it before they could secure it.

The letter goes on to recount how “Next day I went over on my first raid.” Oatis’s memory seems to have played him false: his log book indicates that his next flight—a bombing raid, no longer “special work”— was on September 14, 1918, and this is substantiated by the operations reports of the First Day Bombardment Group. The three squadrons of the Group flew three combined missions that day, and Oatis with Guthrie took part in the first two.58

John Cowperthwaite Tyler, deputy leader for the 11th Aero on the first raid, wrote in his diary that day: “Out at daybreak to start bombing. Bombs just arrived at midnight and no one knew how to put them on. Still working with them and guns, when Major [James Leo Dunsworth] drives up at 7 and orders us off with or without guns and bombs. Only about half loaded, went off.”59 Oatis and Guthrie were flying DH-4 317 on this mission to Conflans-en-Jarnisy, forty-five miles northeast of Amanty and deep inside German-held territory.60 A squadron history recounts how “Led by [Roger Fiske] Chapin, with [Clair Blossom] Laird as his observer, we left the field at Amanty and flew northwest, climbing as rapidly as possible to get our altitude before approaching the lines.” (Oatis’s log book indicates they flew at 9,000 feet.) “Northwest of Verdun we turned to the east, crossed the lines just north of that historic battleground, and headed east in the race for the railroad at Conflans. The first anti-aircraft battery, affectionately known as ‘Archie,’ opened up on us before we were well over the lines.”61

Oatis, writing about this mission in his September 17, 1918, letter, recalled that the archie “didn’t worry us much till we came very near to our objective. Then we saw some very very good shooting. . . . we let our bombs go at our target, and started for home. . . . And then, archie stopped. I was surprised until I glanced around behind us and saw what looked, to poor green Vince, like a million Huns after us. We had to fight, and I assure you it was a hot one. Estimates vary as to the number of Huns there were, but I believe 15 is a conservative estimate.”62 Things looked very grim for this group of pilots, most of whom were as yet inexperienced in combat; fortunately a number of American Spads arrived, and the enemy planes broke off their attack. Before they did, however, two were believed to have gone down out of control. The 11th Aero’s raid report for this mission lists teams entitled to credit for the downed enemy planes; the list does not include Oatis and Guthrie. However, the official list of the 11th’s confirmed victories compiled after the war does.63 Without going into detail in his letter, Oatis noted that once they crossed back over the lines, “We started counting noses then, and found we were not quite so numerous as when we started.” In his log book he recorded “Shoemaker. Groner. Shidler. Sayre lost.”64 It was later learned that Shoemaker, along with his observer Robert Newell Groner, had been shot down and taken prisoner; Horace Greeley Shidler and Harold Holden Sayre, were also shot down; Shidler survived, but Sayre was killed.

A little over two hours after their return to Amanty, Oatis and Guthrie were among the teams from the 11th who, along with planes from the other two squadrons, set out to target Conflans once again, but it was too cloudy, and the 11th returned without dropping bombs.65 “ It was a very peaceable trip.”66

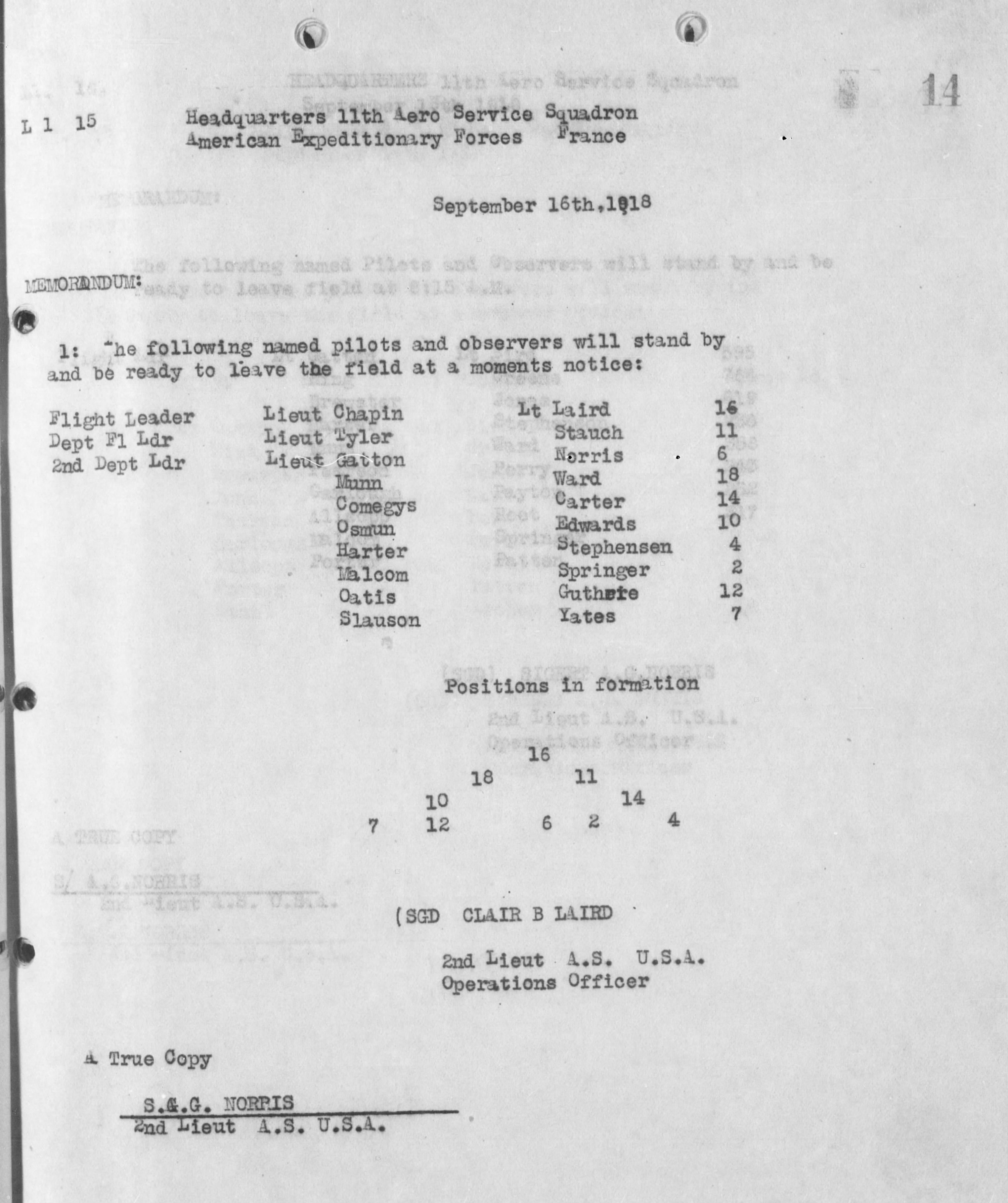

On September 15, 1918, Oatis and Guthrie were among ten teams from the 11th ordered to “stand by and be ready to leave the field at 7:30 A.M. sharp.”67 They did not actually set out until 11:00 on a raid that “was a complete failure. They had insisted on overloading the machines with bombs and the pilots found them almost unmanageable.”68 This was certainly Oatis’s experience: he took his plane as high as 8,000 feet but then had to come down near a French aerodrome at Houdelmont, about twenty miles due east of Amanty, “piled up in a heap with bombs, wings wheels wires etc all mixed up. It was my first ‘good’ smash, and I’m glad it’s out of my system. We tucked our flying clothes under our arms and by begging rides here and there, managed to get home within 36 hours.”69 Although their names appear, assigned to plane 12 at the back of the formation, on standby orders for September 16, 1918, Oatis and Guthrie were not available to fly, and Oatis, although “slated to go on the first trip this afternoon,” does not record a flight in his log book the next day either.70

With the St. Mihiel Offensive completed and the salient wiped out, plans were now well underway for the Meuse-Argonne Offensive to the northwest. However, the First Day Bombardment Group was to remain for a time at Amanty, where there were still “targets of opportunity” and where Pershing wished to continue to focus German attention, away from the secret buildup for the Meuse-Argonne Offensive.71

September 18, 1918, and after

September 18, 1918, Oatis’s twenty-sixth birthday, was another day of inclement weather. Howard Grant Rath of the 96th Aero wrote in his diary that it was assumed no missions could be flown and that some of the pilots of the 11th Aero had been sent to the 1st Air Depot at nearby Colombey-les-Belles to pick up new planes. Thus, when orders came late in the afternoon for the 20th and the 11th to set out on a bombing mission, men were chosen based on who was at Amanty, rather than on an established rota.72 The ten crews from the 11th on this mission included commanding officer Thornton Dayton Hooper, and his observer Ralph Randall Root; the flight leader was Chapin, with observer Laird; Oatis and Guthrie were also among the teams.73 Planes from the 20th Aero set out at 4:24 p.m.74 The 11th followed at 4:45 p.m.75 Hooper was afterwards recalled as saying “I know this is murder, but the swivel chair commanders don’t know it, and all we can do is to go and trust to luck.”76

The objective of this mission is variously described in surviving records. Rath’s “First Day Bombardment Group, Account of Operations” suggests that both the 20th and the 11th were charged with bombing Mars-la-Tour.77 The 11th Aero’s raid report, and Oatis’s log book, give the objective as Lachausée, which was, by this date, just inside the German lines.78 Observer Laird is recorded as describing the raid as : “a bombing mission of railroad yards at Mars le Tour [sic]”79 but also as a mission with “two targets . . . a village with a number of troops and . . . an airdrome ten kilometers across the line.”80 When Laird and Chapin were interrogated after their capture, they were recorded as describing the mission as a “Bombenangriff auf Erdziele im Raum Conflans-Etain” (“bombing raid on ground targets in the area of Conflans-en-Jarnisy and Etain”—both to the north of Lachaussée and Mars-la-Tour).81 The same interrogating German officer understood from Hooper and Root that the mission’s purpose was a “Bombenangriff . . . auf Reserven im Raume Conflans-Etain” (“bombing raid on reserve troops in the area of Conflans-en-Jarnisy and Etain”).82

In any case, ten planes from the 11th Aero flew due north from Amanty to St. Mihiel and then turned northeast for Lachaussée.83 Three planes, those piloted by Cyrus John Gatton, Charles Gross Slauson, and Ector Orr Munn, had to drop out before reaching the lines.84 Clouds made flying, navigating, and keeping formation difficult and also forced the planes to fly at a comparatively low altitude, only 7,000 feet as they crossed the lines just short of Lachaussée.85 A fourth plane, piloted by John Eliot Osmun, turned back after the flight entered a disorienting bank of clouds;86 Oatis recalled that “One fellow lost control and went down in a spin but recovered when he came out of the cloud, and managed to get home safely.”87

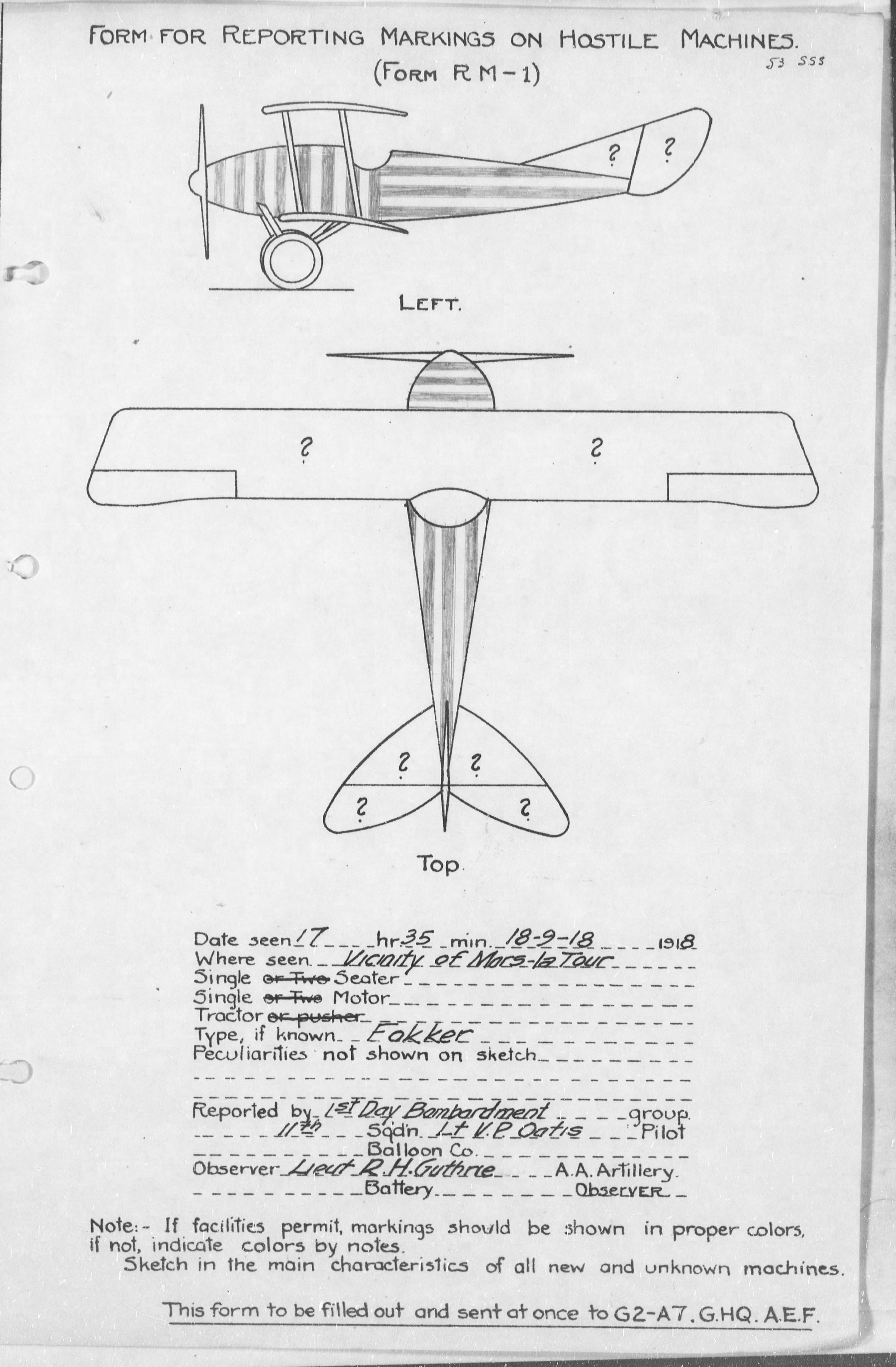

Oatis continues: “The six remaining machines flew around in a circle a couple of times, with a strong wind drifting us farther into Germany all the time. I couldn’t figure out the reason for the maneuver, but it was a case of follow the leader and stick to the formation like glue.” Laird, observer in the lead plane, later recalled that “The target being observed, we circled until break occurred in cloud bank.”88 Thirty-five minutes into the mission, at about 5:35, and apparently somewhat north of Lachaussée in the vicinity of Conflans, the remaining 6 planes of the 11th Aero “came out of one of those clouds, looked around quickly, found our formation all split up into units, and started to get together”—and were attacked by German planes.89

Unusually, there is an account of this engagement from one of the German pilots, Hans Besser, which establishes that the attacking planes were Fokker DVIIs of Jagdstaffel 12.90 Flying at about 13,000 feet, the Fokkers were well positioned to spot the American planes dodging in and out of the cloud cover below them, and, at an opportune moment, to dive on them.91 Both Besser and Oatis remark on the speed of what followed: “Was sich nun abspielte, war Augenblickssache” (“What took place happened in an instant”); “In less than 60 seconds, the outcome of the fight was positively settled.”92 Three DH-4s, those piloted by Tyler, Lester Stephen Harter, and Edward Theodore Comegys, went down in flames. Chapin and Laird’s plane was hit evidently just east of Lachaussée and crash landed into telegraph lines near Chambley-Bussières.93 Hooper’s plane was also hit; he was injured but brought his DH-4 down safely somewhat farther north, in the vicinity of Olley.94 Hooper, Root, Chapin, and Laird were taken prisoner.

Oatis recalled that “Before I cut loose I saw what happened to some of our fellows, but I never saw the others. I made the fastest zigzag run for the nearest cloud, that I could make that bus do. We hadn’t the slightest idea where we were, and only knew the general direction we had to fly to get across the lines.”95 Oatis’s cloud-flying training at Stonehenge was now called into service:

We were above the clouds, the top surface of which was rough and jagged like a stretch of wild mountain country. That is the chief fact that saved our bacon in that long chase. We need[ed] to plunge into a cloud with the whole pack close behind and firing for all they were worth. As soon as we’d get into a cloud, I’d turn just enough to bring us out in a slightly different direction. That stunt worked every time. The Huns would be waiting for us on the other side of the cloud but evidently didn’t give us credit for sense enough to use a little horse sense. Each time we came out of a cloud we would have just a little start on them before they picked us out and started the chase again.96

Oatis was confident that Guthrie had been able to shoot down one of their pursuers, and, although he thought that “It happened too far behind the lines to be recognized officially,” they were later credited for it.97 Matching claims to casualties is a fraught business, but it may be that Erich Kämpfe of Jasta 13, wounded near Chambley on this day, was Guthrie’s target.98

After twenty minutes of dodging and diving, pursued by enemy aircraft—perhaps from a different German squadron, as Besser describes the pilots of Jasta 12 landing at their aerodrome immediately after their fight—and hindered by the fact that the plane’s “bomb dropping device . . . refused to operate so that there was further hindered [sic] in manoeuvring [sic] by 200 kilograms of dead weight,”99 Oatis and Guthrie crossed the lines at Damloup north of Verdun and then flew south, still pursued by a single German plane.100 “Never since I’ve started flying, have I ever wanted so much to land, as I did just then. I figured out every little possibility, and I knew I could get within ten feet of the ground without much danger, but if Fritz wanted to he could nail us easily when we straightened out for the final point of getting onto the ground. So we kept on running and fighting till he finally gave up and left us”; this happened in the vicinity of Ambly-sur-Meuse.101 Oatis and Guthrie arrived back at Amanty at 6:30 and, according to Rath, reported that “‘we are the formation’.”102 Afterwards they filed a report describing a German plane they had sighted at 5:35 near Mars-la-Tour.103 Much later, after the armistice, Oatis was told that German officials believed that all the planes in the flight had been shot down.104

The squadron waited in vain for other planes from the mission to return. Seven pilot/observer teams from the 11th Aero had now been lost—two on September 14, and five on September 18, 1918—whether killed or taken prisoner, the squadron could not be sure.

No missions were flown by squadrons of the First Day Bombardment Group from September 19 through September 25, 1918. On September 24 and 25, 1918, the squadrons were relocated from Amanty twenty miles northwest to Maulan, from the St. Mihiel to the Meuse-Argonne front (they were joined there by the not-yet-operational 166th Aero). Oatis was one of many not happy with the new location: “a terrible aerodrome. Our particular spot on it was hardly wide enough for two machines to get off together.”105

Just before the move, new pilots were assigned to the 11th, including Dana Edmund Coates, Ralf Andrews Crookston, Charles Louis Heater, and George Dana Spear from the second Oxford detachment and Alfred Clapp Cooper of the first Oxford detachment, as well as William Wallace Waring, whom Oatis had probably known at Waddington.106 Uel Thomas McCurry, of the second Oxford detachment, would arrive soon after the move to Maulan. Of these men, only McCurry and Heater had had operational experience.107 Heater’s, with No. 55 Squadron R.A.F., flying DH.4s, was extensive and warranted his being appointed the squadron’s new commanding officer, taking Hooper’s place.

Heater lectured the remaining and new pilots of the 11th Aero “on the primary importance of close, tight formations and also my confidence in the D.H.4, although I had not flown one with a Liberty motor.”108 He had them watch as he put a DH-4 through its paces, and when weather permitted he had them practice formation flying. Meanwhile, there was consultation among squadron leaders and higher-ups that led to the decision to fly larger formations over the lines—twelve to eighteen planes, combining planes from more than one squadron as needed to make up a flight.109 The squadron history describes “the reconstruction of a broken outfit and its complete transformation into a high grade, competent unit, confident of its ability and proud of its record.”110

The Meuse-Argonne Offensive

The Meuse-Argonne Offensive opened in the very early hours of September 26, 1918. That morning the First Day Bombardment Group was tasked with bombing Dun-sur-Meuse, an important German transport center, approximately fifty miles north of Maulan and approximately twelve miles over the lines. Four flights set out between 8 and 9:00, two from the 20th, and one each from the 96th and the 11th.111 Oatis and Guthrie in DH-4 no. 12 were part of the flight of ten teams from the 11th led by Gatton. According to Oatis’s log book, he and Guthrie returned because of “motor trouble”; all but one of the other planes returned early as well: “Things went wrong. Our formation broke up and returned without crossing the lines.”112

In the afternoon the 11th, followed by the 20th, targeted Etain, a few miles over the lines east of Verdun. Seven of eight teams from the 11th, again led by Gatton, and including Oatis and Guthrie, reached an altitude of 13,000 feet in good weather, encountered no enemy aircraft, and dropped bombs on the town.113 Oatis’s log book note “AA good . . . 3 shrapnel holes in aileron.” Nonetheless, the squadron history recalled that “This was the first successful raid we had made in comparative safety and everyone could notice the improved morale resulting from it.”114

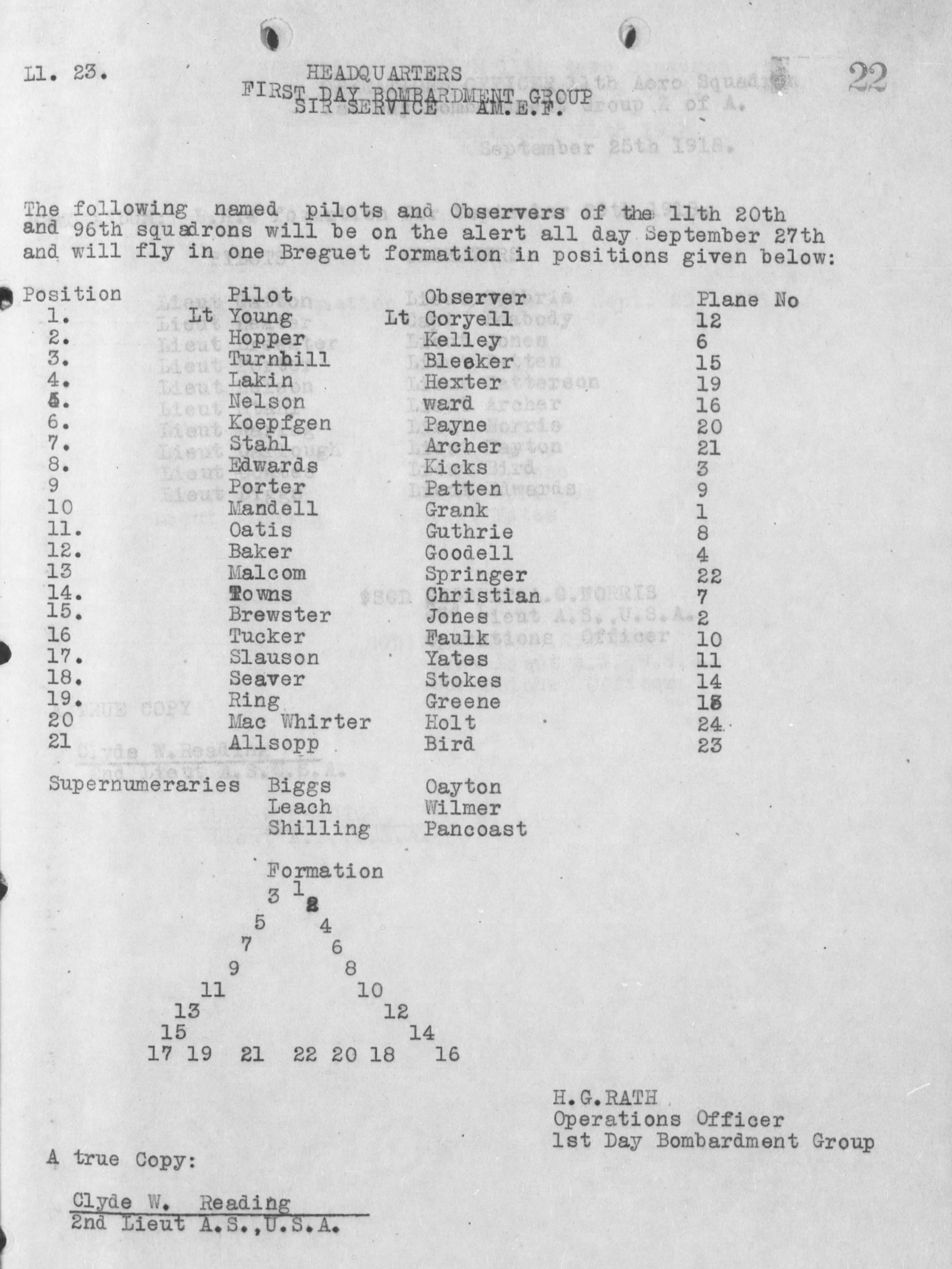

The next day, September 27, 1918, the First Day Bombardment Group squadrons, perhaps more out of necessity than by design, flew in a single large formation for the first time. The 96th Aero had lost many pilots and observers, but was well supplied with Breguet 14 B.2 planes. For that day’s single mission, the 11th and the 20th each loaned at least seven teams to supplement the two teams from the 96th. Pilots from the 11th included Oatis (with Guthrie). Given Oatis’s antipathy for Breguets, he was perhaps relieved when ten minutes into the flight he found his plane had a bad motor; his log book indicates he “crashed landing,” but evidently with no harm to himself or Guthrie. This was the only time he flew a Breguet operationally.

Oatis did not take part in the similar combined mission the next morning (September 28, 1918), but instead, according to his log book, brought a new DH-4 to Maulan from the Advance Air Depot at Behonne. He and Guthrie made a test flight the next day. Oatis did not take part in the late afternoon mission on September 29, 1918, although Guthrie is recorded as participating as flight leader Gatton’s observer.115 No missions were flown on the last day of the month.

Stocktaking at the end of September 1918 showed impressive numbers of missions undertaken by the squadrons of the First Day Bombardment Group, but also a distressing number of casualties—thirty-eight men “missing,” distributed fairly evenly among the three squadrons (the 166th was not yet operational).116

On October 1, 1918, Oatis, with Guthrie as his observer, served as flight leader for the first time. The mission consisted of a large formation of Breguets flown mainly by men from the 96th but also some loaned from the 11th, followed in short order by a large and unwieldy formation of DH-4s from the 11th and 20th; the target was Bantheville.117 “[T]he formation was in fearful shape when they approached the lines. Lieutenant Guthrie lost his helmet and goggles at this juncture and became blinded by the cold wind. Oatis attempted to get him down from the high altitude and succeeded only in breaking up the entire formation, which followed him mournfully home.”118

The next day’s mission was similarly constituted, i.e., a formation of Breguets followed by one of DH-4s. The flight leader for the DH-4 formation was Cecil Grey Sellers from the 20th, with Oatis, second deputy leader, in a plane just behind and to the left of him. Guthrie was scheduled to fly with Oatis, but William F. Jacobs, one of the enlisted man who volunteered when observers were in short supply, flew instead. Guthrie was perhaps still suffering from flying at high altitude without helmet and goggles the previous day. While the Breguets bombed Cornay, fourteen of the DH-4s, flying at nearly 15,000 feet, reached and bombed St. Juvin—an important road junction just north of the Forest of Argonne and about forty-eight miles north-northeast of Maulan—at 11:25 before returning home safely.119 The efforts of this day were noted in the First Army’s intelligence report for October 2, 1918: “Our bombing planes dropped a considerable amount of bombs on the town [sic] of St-Juvin and Cornay.”120

On October 3 and 4, 1918, Oatis was occupied with testing DH-4s and bringing a new DH-4 to the aerodrome. On October 5, 1918, during the second mission of the day, Oatis flew with observer Jacobs in a twenty plane DH-4 formation made up of teams from the 11th and 20th.121 Oatis and Jacobs were among the fifteen teams that, flying at 13–15,000 feet, reached their targets: Saint-Juvin,122 Aincreville,123 and Doulcon,124—three towns lying between Grandpré and Dun-sur-Meuse.

Oatis did not fly in the next day’s missions (nor did Guthrie), and no missions were flown on October 7 and 8, 1918. Oatis and Guthrie flew as a team again the next day, October 9, 1918, during an early afternoon mission in which ten DH-4s from the 11th set off at 2:10 p.m., with Oatis leading in DH-4 No. 12, followed ten minutes later by a slightly larger flight from the 20th. Oatis and Guthrie were among the six teams from the 11th that reached and bombed Bantheville at 3:25; all planes returned safely to the aerodrome.125 Oatis was surely relieved that the mission had gone well, as he had been chagrined about the raid on October 1, 1918, and took the leadership responsibility very seriously.126

Oatis was not among the pilots on the two large multi-squadron missions flown on October 10, 1918, although Guthrie again served as observer to the flight leader of the 11th, Gatton, on both of them. In passing I note that these were the last missions that involved the 11th and 20th squadrons loaning pilots to the 96th to fly their Breguets. A period of bad weather followed, and the squadrons of the First Day Bombardment Group had a week in which no missions were flown.127

Clouds and mist hindered visibility on October 18, 1918; nevertheless a large mission, now including for the first time planes from the 166th Aero, set off in the early afternoon to bomb Bayonville, “junction of six minor roads . . . and a key marshalling area and logistics facility of the German defense.”128 Oatis, with Guthrie as his observer, was flight leader for the sixteen teams from the 11th, including, unusually, squadron commander Heater and his observer, Sigbert Albert George Norris (who also served as the squadron’s operations officer). Eleven teams from the 11th, including Oatis and Guthrie, reached the objective and returned safely a little over two hours after setting out on this highly successful mission.129 Oatis noted in his log book that “Huns appeared but were driven off by Spads.”

On October 23, 1918, after four days of unfavorable weather, Oatis with Guthrie set off twice, leading the planes of the 11th on raids. On the first one, targeting Buzancy in the early morning, Oatis “Broke prop taking off. Returned”; four other planes from the 11th also did not reach the objective, but eight did. In the afternoon, however, Oatis with Guthrie in their usual plane, DH-4 12, successfully led the 11th squadron as part of a four-squadron mission to bomb Bois de la Folie and Bois de Barricourt.130 Apropos of this mission, Oatis noted in his log book “166 had stormy time”; Fokkers focussed on the planes of this squadron, and both Paul Vincent Carpenter and Fremont Cutler Foss of the 166th had to make forced landings on their return flights.

Again on October 29, 1918, Oatis with Guthrie set out twice, but had to return from the first mission, this time because of a bad motor. In the afternoon Oatis, with Guthrie, led his squadron, “following 166th,” as part of a successful four-squadron bombing raid on Damvillers. On October 30, 1918, and again on November 3, 1918, Oatis with Guthrie took part in two missions each day, leading the flight made up of planes of the 11th Aero. On November 3, 1918, the 11th dropped bombs on Martincourt-sur-Meuse in the morning and Beaumont-en-Argonne in the afternoon; these towns were sixty miles north of Maulan, and the flight out and back in the afternoon took nearly two and a half hours.131 During the afternoon mission, the 11th Aero was attacked by eight Fokkers just south of Beaumont, two of which were seen to go down out of control. Gerald C. Thomas notes that “Because of the tight formation the Fokkers were never able to close in for an effective attack”; Oatis, writing more generally about his experiences recalled that “With the exception of our first two raids, and our last one, we never lost a machine over the lines. . . . Our success in that respect was [due] almost entirely to the excellent formation we flew after we learned our lesson early in the game.”132 All members of the flight, including Oatis and Guthrie, were given credit for the planes downed on November 3, 1918.133

Oatis did not fly the next day (Stahl served as flight leader instead). The objective specified for the three DH-4 squadrons of the First Day Bombardment Squadron on November 5, 1918, was Mouzon, yet farther north.134 However, about fifteen miles short of the objective, the planes of the 11th Aero, led by Oatis were finding they could not keep up with the 20th and 166th, and the 11th’s part in the mission was cut short.135 Allsopp noted in his carnet that he had flown as “far as Bayonville—back as only 5 in form[ation],” while Oatis wrote in his log book “Our formation reduced to five. Returned home without crossing line.” That they were still within Allied territory at Bayonville is an index of the success of the Meuse-Argonne Offensive. This November 5, 1918, raid was the last operational mission flown by the squadrons of the First Day Bombardment Group.

Afterwards

In an undated letter to his father written shortly after the armistice, Oatis looked back on his time with the 11th, noting of his time as flight leader that “no man has ever gone down behind me. That was purely good fortune but it is something to be happy over.” He was also glad to report that he had been recommended for a captaincy, despite knowing that the end of the war meant the promotion would not happen. A slightly later letter carried the welcome news that his first squadron commander and his observer had survived and were now in hospital in Toul; Oatis flew over to visit them. Constrained by censorship rules, Oatis does not name the men, but it is clear from his account that they were Hooper and Root: “Gee but it was good to see them again after we had mourned them as lost.”

Oatis and Stahl were now planning a well-earned leave at Nice and Cannes. Before they set out, news came that they would be among the first to return home. Stahl recalled that “on Dec. 5 came the order which started [him] and nine of his companions back to the United States and peacetimes.”136 Oatis’s last letter to his father was dated December 8, 1918, and written at Romorantin: “Stahl and I are starting on leave. Not sure where will go as we can’t afford to be away too long in case homeward orders come in.” Oatis and Stahl sailed on the U.S.S. Princess Matoika from St. Nazaire on January 30, 1919, and arrived at Newport News, Virginia, on February 11, 1919. Later that year, Oatis and Guthrie were awarded the Silver Star for their actions on September 18, 1918, when, alone of their formation, they succeeded in returning from the mission, having shot down an enemy aircraft.137

Oatis initially returned to his family in Ohio, but soon resettled in Illinois, residing in Evanston and working in Chicago as an investment banker at V. P. Oatis, a successor firm to Sydney Spitzer & Co.138

mrsmcq March 23, 2021; revised, based on letters, and reposted June 19, 2023

Notes

(For complete bibliographic entries, please consult the list of works and web pages cited.)

1 Oatis’s date and place of birth are taken from Ancestry.com, U.S., World War I Draft Registration Cards, 1917–1918, record for Vincent Paul Oatis. His place and date of death are taken from “Vincent P. Oatis.” The photo is a detail from Payden’s photo of Oatis, Pudrith, and Middleditch.

2 Information on Oatis’s family is taken from documents available at Ancestry.com.

3 Ancestry.com, 1940 United States Federal Census, record for Vincent Oatis, indicates that he had four years of college. “Vincent P. Oatis” (obituary) notes that he was a “graduate of old St. John’s University.” This Jesuit school began as an academy (high school) in 1898; students from the first class became the first students of the university in 1902. The depression economy forced it to close in 1936. See “Our Proud History.” On Oatis’s connection with the Toledo News-Bee, see “Former Reporter in Aviation Corps.”

4 “City Council”; “New Firm Takes over Spitzer Organization.”

5 Oatis, letters of June 27 and 28, 1917. I am grateful to Daniel J. Polglaze for access to Oatis’s letters, most of which were written to Oatis’s father, Peter Oatis, as well as for scans of Oatis’s pilot’s flying log book.

6 “Ground School Graduations [for September 1, 1917].”

7 Oatis, letter of July 17 [1917].

8 Oatis, letter of August 22, 1917.

9 Oatis, letter of September 6, 1917.

10 Oatis, letter of September 16, 1917.

11 Oatis, letter of October 1, 1917.

12 See Oatis’s letters of October 5 and 22, 1917, for his assignments to Queen’s and Exeter. See the War Birds entry for October 22, 1917, for one of many accounts of the events that prompted the change of residence.

13 Oatis, letter of October 5, 1917.

14 Oatis, letter of October 22, 1917.

15 Ibid.

16 For the names of the men sent to training squadrons in mid-November, see Foss, diary entry for November 15, 1917.

17 Oatis, letter of December 11, 1917.

18 Oatis was not unusual in leaving off the letter prefix of his planes’ serial numbers; the letters can be supplied by consulting Robertson, British Military Aircraft Serials 1878–1987. On Orpen, see The National Archives (United Kingdom), Royal Air Force officers’ service records 1918–1919, record for Claude Millerd Orpen.

19 On Body, see The National Archives (United Kingdom), Royal Air Force officers’ service records 1918–1919, record for Graham Campbell Body.

20 Oatis, letter dated December 11, 1917.

21 See Oatis, letter of December 11, 1917: “You have to do five hours of solo flying and make fifteen landings. Then you pass into the advanced squadron and start flying real aeroplanes.” Unless otherwise noted, information on Oatis’s flying is based on his log book.

22 See Oatis’s letters of December 11, 1917, continued on December 14, 1918, “there is a reward of 4 days leave when you finish your elementary solo, and three of us were counting on going to London tonight”; and January 14 and April 14, 1918.

23 On Hornby, see The National Archives (United Kingdom), Royal Air Force officers’ service records 1918–1919, record for Roland Godefroy Hornby.

24 Oatis, letter of January 14, 1918.

25 Oatis’s log book entry for his fifteen-minute DH.4 flight with Body appears out of chronological order after the entry for January 21, 1918. That the date of January 14 is correct is substantiated by a passage in the letter of the same date: “Ever since Jan 1 I’ve been waiting my chance to get a couple of hours instruction on a fast service machine but have had only 15 minutes so far.”

26 Cables 652-S and 900-R.

27 Oatis, letter dated February 9, 1918, evidently continued on subsequent days; see also his log book entries for the afternoon of February 12, 1918.

28 See Oatis’s undated (early April 1918) letter to “friends” on Sidney Spitzer & Company letterhead regarding the planes used at No. 48 T.S. His pilot may have been Arthur Francis Brooke, who, according to his casualty form, was in England at this time; see “2nd Lieut., Captain A. F Brooke.”

29 Oatis’s undated (early April 1918) letter.

30 See, in addition to entries in Oatis’s log book, his account of this trip in his letter of March 12, 1918.

31 On Tooth, see The National Archives (United Kingdom), Royal Air Force officers’ service records 1918–1919, record for Alfred Gordon Tooth.

32 Biddle, “Special Orders No. 35.”

33 Oatis, letter of April 14, 1918.

34 Several letters by Oatis, as well as ones by Vollmayer, appeared in the Toledo News-Bee, much of which is digitized in the Google newspaper archives; however, I have not been able to find this one.

35 Oatis, letter of April 14, 1918; on this raid, see Castle, Zeppelin Raids, Gothas and ‘Giants’, page for 12/13 April 1918.

36 Oatis does not record the altitude in his log book, but see his letter of April 14, 1918: “Before we leave we have to pass some tests, such as climbing to 17,000 ft.”

37 Oatis, letter of May 18, 1918.

38 See The National Archives (United Kingdom), Royal Air Force officers’ service records 1918–1919, record for William Buckingham. Oatis records this as Avro [B]8729; this is the last instance in which Oatis records a serial number in his log book.

39 See The National Archives (United Kingdom), Royal Air Force officers’ service records 1918–1919, record for Henry Hollingdrake Maddocks.

40 See The National Archives (United Kingdom), Royal Air Force officers’ service records 1918–1919, record for Leslie Peech Aizlewood.

41 Oatis, letter of June 18, 1918.

42 Oatis, letter of July 12, 1918.

43 See Barber, Stonehenge Aerodrome and the Stonehenge Landscape, p. 19.

44 Oatis, letter of July 12, 1918.

45 Oatis, letter of July 12, 1918.

46 [Biddle?], “Special Orders No. 109.”

47 Oatis, letter of July 12, 1918; Goettler, diary entry for July 8, 1918.

48 Goeetler, diary entry for July 10, 1918.

49 Oatis, letter of July 12, 1918.

50 On Stahl’s presence at the 7th A.I.C. see “When Hell Broke Loose,” p. 9.

51 Oatis, letter of August 5, 1918.

52 Oatis, letter of August 25, 1918, (evidently continued on a later day). Patrick, “Final Report,” p. 50, states that “it was not until September, 1918, that the school [at Clermont-Ferrand] received DH-4 airplanes.” However, “Seventh Aviation Instruction Center, Clermont-Ferrand (Puy-de-Dome), France,” p. 221, indicates that DH-4s began arriving on July 18, 1918. In addition to Oatis’s account and log book, Clifford Walter Allsopp’s carnet (log book) records his flying a “Liberty” on August 30, 1918. Note: Conventionally, “DH.4” refers to the British plane, “DH-4” to the American-built version of the same plane.

53 See The National Archives (United Kingdom), Royal Air Force officers’ service records 1918–1919, record for Frank Simpson Whiting.

54 This accords with the date of assignment provided in the roster on p. 4 of “11th Squadron” for Oatis and a number of other pilots and observers. I should note that Thomas, The First Team, p. 56, indicates that a (this?) group was assigned on September 9, 1918, and this date is supported by Tyler’s diary entry for September 9, 1918, as well as by the account on p. 114 of History of the 11th Aero Squadron U.S.A.

55 “First Day Bombardment Group,” p. 4.

56 Maurer, The U.S. Air Service in World War I, vol. 3, p. 120 (editorial comment). Note: many of the documents in this volume are also available in Gorrell.

57 See Thomas, The First Team, pp. 67–68, regarding the work of the 11th (and 20th) Aero on September 11 and 12, 1918.

58 Rath, “First Day Bombardment Group, Account of Operations,” pp. 94–97. Rath provides a list of pilots and observers of the 11th on the first mission flown that day that differs from the list that can be reconstructed from the 11th Aero’s own raid report and from accounts of planes and men lost. See “11th Squadron,” p. 61; Tyler, Selections from the Letters and Diary, p. 127; History of the 11th Aero Squadron U.S.A., p. 151; Thomas, The First Team, p. 72; and Robert Newell Groner’s statement that ten machines set out, but three had to turn back before crossing the lines (Presenting the Experiences of Air Service Officers who were Prisoners of War in Germany, p. 133).

59 Tyler, Selections from the Letters and Diary of John Cowperthwaite Tyler. (See Rath and Harrington, First to Bomb, pp. 94–96 and passim, for a sympathetic account of the much-maligned Dunsworth.)

60 Rath, “First Day Bombardment Group, Account of Operations,” p. 94.

61 History of the 11th Aero Squadron U.S.A., p. 149.

62 This is also the number given in the History of the 11th Aero Squadron U.S.A., p. 151; Rath, “First Day Bombardment Group, Account of Operations,” p. 97, records 7, and the 11th Aero raid report (“11th Squadron,” p. 61) records 7– 9. The red-nosed planes (History, p. 151) may have been Fokkers of Jasta 15, stationed at Tichémont, just northeast of Conflans. []

63 “Confirmed Victories 11th Aero Squadron,” p. 6.

64 Oatis appears to have been unhappy with how he was keeping his log book and recopied / rewrote some entries starting September 12, 1918, tearing out the page(s) with the original entries. The log book entries are thus not truly contemporaneous.

65 Rath, “First Day Bombardment Group, Account of Operations,” p. 95, indicates that they “Bombed and reached Vittonville and Arnaville,” but this is evidently in error.

66 Oatis, letter of September 17, 1918.

67 “11th Squadron,” p. 9 (which has them flying plane 521; Rath, “First Day Bombardment Group, Account of Operations,” p. 98, puts them in 821).

68 History of the 11th Aero Squadron U.S.A., p. 153.

69 Oatis, letter of September 17, 1918; and see his log book.

70 Oatis, letter of September 17, 1918. Rath, “First Day Bombardment Group, Account of Operations,” p. 103; and History of the 11th Aero Squadron U.S.A., p. 153, both indicate no missions were flown on September 17, 1918. “11th Squadron,” p. 54, based apparently on an undated raid report, p. 65, describes a mission to Conflans that day; this is one of the many unresolved discrepancies among the sources for the history of the 11th Aero.

71 Thomas, The First Team, p. 79. According to Maurer, “In preparing for the Argonne-Meuse operations the 1st Day Bombardment Group was ordered to carry out bombing expeditions to objectives east of the Moselle river. The object was to convey the impression of an impending attack on Metz, and thus avert the enemy’s attention from the real point of attack” (The U.S. Air Service in World War I , vol. 1, p 371). The sources available to me do not record any such “expeditions east of the Moselle” having been undertaken.

72 Rath, diary entry for September 18, 1918.

73 See Rath, “First Day Bombardment Group, Account of Operations,” p. 104, for the names of the ten crews, and the raid report on p. 66 of “11th Squadron” for the leaders.

74 Rath, “First Day Bombardment Group, Account of Operations,” p. 103; Rath, diary entry for September 18, 1918. The 20th Aero’s raid report records the departure time as 16:10 (“History of the 20th Aero Squadron, 1st Army,” p. 217).

75 “11th Squadron,” p. 66; Rath, diary entry for September 18, 1918.

76 History of the 11th Aero Squadron U.S.A., p. 153.

77 Rath, “First Day Bombardment Group, Account of Operations,” pp. 103–04.

78 “11th Squadron,” p. 66.

79 See his account on p. 175 of Presenting the Experiences of Air Service Officers who were Prisoners of War in Germany.

80 “Captured by the Germans.”

81 Kraft, [Documents], p. 28.

82 Ibid., p. 29.

83 “First Day Bombardment Group, Account of Operations,” p. 104, gives number;“11th Squadron,” p. 66, gives route.

84 Based on comparison of Rath, “First Day Bombardment Group, Account of Operations,” p. 104, and History of the 11th Aero Squadron U.S.A., p. 153: “Seven machines crossed the lines.”

85 History of the 11th Aero Squadron U.S.A., p. 153.; cf. “11th Squadron,” p. 66. Oatis, letter of (about) September 25, 1918.

86 History of the 11th Aero Squadron U.S.A., p. 155

87 Oatis, letter of (about) September 25, 1918.

88 Presenting the Experiences of Air Service Officers who were Prisoners of War in Germany, p. 175.

89 Oatis, letter of (about) September 25, 1918. “11th Squadron,” p. 66 (raid report) gives the time of the encounter as 17:20; Rath, “First Day Bombardment Group, Account of Operations,” p. 104, citing Guthrie (“the surviving observer”) indicates that the attack began at 17:35.

90 The account is transcribed on pp. 84–86 of Möller’s Kamp und Sieg eines Jagdgeschwaders. See also the translation of Besser’s account on pp. 355–57 of Duiven, “Das königliche preussische Jagdgeschwader Nr. II,” part 2.

91 See Besser, quoted by Möller, Kamp und Sieg eines Jagdgeschwaders, p. 84.

92 Besser, quoted by Möller, Kamp und Sieg eines Jagdgeschwaders, p. 84; Oatis, letter of (about) September 25, 1918.

93 See Laird’s statement on p. 175 of Presenting the Experiences of Air Service Officers who were Prisoners of War in Germany”; in Kraft, [Documents], p. 27, the location is given as east of Hagéville.

94 See Root’s statement on p. 267 of Presenting the Experiences, and Kraft [Documents], p. 29.

95 Oatis, letter of (about) September 25, 1918.

96 Oatis, letter of September 29, 1918.

97 Oatis, letter of (about) September 25, 1918. “Confirmed Victories 11th Aero Squadron,” p. 6. See also Rath, diary entry for September 18, 1918: “they shot down one E.A.”

98 Kämpfe succumbed to his wounds two days later. See entry in Graeme’s list at “aerobatics or really out of control”; see also Ludwig-Maximilians-Universität München, Personalstand der Ludwig-Maximilians-Universität München Sommer-Halbjahr 1919, p. III.

99 Besser in Möller, Kampf und Sieg eines Jagdgeschwaders, p 85; Rath, “First Day Bombardment Group, Account of Operations,” p. 105

100 The raid report on p. 66 of “11th Squadron” indicates that they “crossed lines at “Damloue”; History of the 11th Aero Squadron U.S.A., p. 155, indicates they were “north of Verdun” when they crossed the lines. This would match the location of Damloup.

101 “11th Squadron,” p. 66.

102 Rath, diary entry for September 18, 1918.

103 Air Intelligence, Second Section, G.S., p. 53 sss.

104 Oatis, letter of November 24, 1918.

105 Oatis, letter of November 24, 1918.

106 See Oatis’s letter of December 11, 1917, regarding Waring.

107 Information on Cooper and Waring is scarce, but I find no record of their having been attached to an R.A.F. squadron or of work with an American squadron prior to their assignment to the 11th Aero. McCurry had been with the 8th Aero; the squadron documentation is insufficient to determine the extent of McCurry’s operational flying.

108 Heater, quoted in Skinner, “Commanding the 11th,” p. 264.

109 Maurer, ed. The U.S. Air Service in World War I, vol. 1, p. 372.

110 History of the 11th Aero Squadron U.S.A., p. 159.

111 Rath, “First Day Bombardment Group, Account of Operations,” 106–09 (which should be reordered: 106, 108, 109, 107); “History of the 20th Aero Squadron, 1st Army,” p. 218.

112 History of the 11th Aero Squadron U.S.A., p. 159; Waring with observer Sigbert Albert George Norris was the exception; they joined the planes of the 20th and provided protection that led to their being recommended for the D.S.C.

113 Rath, “First Day Bombardment Group, Account of Operations,” p. 107; “11th Squadron,” p. 67.

114 History of the 11th Aero Squadron U.S.A., pp. 159, 161.

115 Rath, “First Day Bombardment Group, Account of Operations,” p. 111.

116 Ibid., pp. 113–14.

117 Rath, “First Day Bombardment Group, Account of Operations,” pp. 115–16.

118 History of the 11th Aero Squadron U.S.A., p. 163. See also Oatis’s account of this flight in his letter of October 7, 1918.

119 Rath, “First Day Bombardment Group, Account of Operations,” pp. 116–17; operations orders with formation sketch on p. 27 of “11th Squadron.” The raid report on p. 73 of “11th Squadron” indicates the altitude, as do the relevant entries in Oatis’s and Coates’s log books.

120 United States, Department of the Army, Historical Division, United States Army in the World War, 1917-1919, vol. 9, p. 198.

121 The operations order on p. 33 of “11th Squadron” lists eighteen planes, while Rath, “First Day Bombardment Group, Account of Operations,” pp. 120–21, lists twenty teams.

122 “11th Squadron,” p. 76. Note: Thomas, The First Team, p. 98, mistakenly identifies this mission as one undertaken at low altitude—the low-altitude raid was made on October 6, 1918; see entry in Coates’s log book.

123 “History of the 20th Aero Squadron, 1st Army,” p. 226; Oatis, pilot’s flying log book.

124 Rath, “First Day Bombardment Group, Account of Operations,” p. 121.

125 Rath, “First Day Bombardment Group, Account of Operations,” pp. 123–24.

126 See his letter of October 7, 1918.

127 Rath, “First Day Bombardment Group, Account of Operations,” , pp. 125–28.

128 Thomas, The First Team, p. 101.

129 Rath, “First Day Bombardment Group, Account of Operations,” pp. 129–30; “11th Squadron,” p. 80.

130 Rath, “First Day Bombardment Group, Account of Operations,” pp. 131–33.

131 “11th Squadron,” pp. 87 and 88.

132 Oatis, letter of November 24, 1918; “our last one” refers to the November 4, 1918, mission, when pilot Coates and his observer were shot down.

133 “11th Squadron,” p. 88; “Confirmed Victories 11th Aero Squadron,” p. 6. According to the latter, Oatis and Guthrie were each credited with a total of 4 victories. However, the “Individual Victory List,” pp. 51 and 52, credits Oatis and Guthrie with three victories each. It is not clear why Thayer, America’s First Eagles, credits Guthrie with four (p. 320) but Oatis with three (p. 321).

134 Oatis’s log book records this mission under the date November 6, 1918, but comparison with Allsopp’s carnet and Rath, “First Day Bombardment Group, Account of Operations,” pp. 150–51, support the November 5, 1918, date.

135 Allsopp, Carnet, entry for November 5, 1918; History of the 11th Aero Squadron U.S.A., p. 175.

136 “When Hell Broke Loose, Stahl was Busy ‘Over There’,” p. 10.

137 “Vincent P. Oatis” [web page], and “Ramon H. Guthrie.”

138 See documents available at Ancestry.com.