(New Orleans, March 7, 1895 – Great Neck, Long Island, New York, November 5, 1971).1

Although Chalaire was born in New Orleans, the family had moved to New York City by the time he was five; his father was connected with the theater.2 Chalaire attended the High School of Commerce, graduating in 1912.3 He became a reporter for the New York Herald and attended New York University, receiving a Bachelor of Law in 1916.4 When he registered for the draft on May 30, 1917, he was supporting his Dresden-born, widowed mother and was a candidate at Plattsburg, New York, for the Officers’ Reserve Corps. He was selected to attend ground school at M.I.T., from which he graduated on August 25, 1917.4a

Along with about one third of his ground school classmates, Chalaire chose or was chosen for flight training in Italy and was thus one of the 150 men of the “Italian” or “second Oxford detachment” who sailed to England on the Carmania. They departed New York for Halifax on September 18, 1917, and departed Halifax as part of a convoy for the Atlantic crossing on September 21, 1917. The men of the detachment travelled first class and enjoyed shipboard leisure, including concerts featuring the violinist Albert Spalding, who was on his way to Italy. They also had Italian lessons, conducted by Fiorello La Guardia. Once the convoy entered dangerous waters, the men took turns at submarine watch. Jacob Kirkbride Milnor noted in his diary on September 28, 1917, that “Immediately after dinner the ‘Sunday Guard’ assembled on the boat deck, in charge of Walter Chalaire, for instructions on ‘Guard Mount’ and pistol inspection.” There was an easing of tension when U.S. and British destroyers appeared the next day to accompany the convoy through the danger zone.

When the Carmania docked at Liverpool on October 2, 1917, the detachment learned to their initial consternation that they were not to go to Italy, but to remain in England and repeat ground school at the Royal Flying Corps’s No. 2 School of Military Aeronautics at Oxford University. In preparation for this they were, on October 6, 1918, according to the relevant entry in Milnor’s diary, “marched up to the Museum, where all classes are held, and were divided into squads (working squads) of eight men. Ours was No. 7 with ‘Charlie’ Chalaire in charge.” There are at least two extant photos from this period that include Chalaire. One shows him, Harold Kidder Bulkley, and an unidentified cadet with bicycles; in another he is standing alongside Bulkley, Donald Elsworth Carlton, and Henry Bradley Frost.

Chalaire’s R.A.F. service record indicates that, instead of going from Oxford to Grantham with most of the second Oxford men, he set off on November 5, 1917, for the No. 1 Training Depot Squadron at Stamford. He was thus among the twenty men chosen by Elliott White Springs to go to Stamford, even though Chalaire, unlike most of the others Springs selected, had apparently not had any experience in the air.5 Just two days later, according to an entry in Fremont Cutler Foss’s diary for November 7, 1917, Chalaire, along with Arthur Richmond Taber, Frank Aloysius Dixon, and other men stationed at Stamford were at Grantham for a visit. And at Thanksgiving, Chalaire and many of the second Oxford men from Stamford and other flying schools were once again at Grantham. Chalaire wrote a lively description of the festivities, which included a football game between the “Unfits” and the “Hardly Ables,” that was published in U.S. papers.6

On January 16, 1918, along with William Ludwig Deetjen, Carlton, and Julian Carr Stanley, Chalaire travelled from Stamford via Grantham to Waddington in Lincolnshire and No. 44 Training Squadron. There they learned that this was, as Deetjen described it, “only a pool squadron . . . where men are held till the upper squadrons are emptied.” Soon thereafter, Chalaire, Carlton, and Stanley were assigned to No. 48 Training Squadron, while Deetjen went to No. 51. Both squadrons were at Waddington where, according to Deetjen, the aircraft available were “Rumpeties (Maurice Farmans), Martinsydes, R.E.8s, deH6’s, BE2E’s, and deH4’s.”7

On February 9, 1918, Chalaire and Carlton attended the wedding in Lincoln of Annie Courtney Willimott and Sub-Lieutenant Cyril Kay, R.N.R.; Chalaire was best man.8 Deetjen reports of Chalaire in mid-February that he “got a straf for hedge-hopping and herding sheep.”9 Only a few days later, on February 19, 1918, Chalaire and Carlton set off cross country; Carlton crashed and died at Spitalgate. Deetjen wrote in his diary: “Chalaire saw [the crash] and thought it was a large A.W. [Armstrong Whitworth], and reported so at Spitellgate [sic]. He never knew till later that it was Don.”10

I have not been able to find information on Chalaire’s training after his time at Waddington. By sometime in the latter half of February 1918 he had completed enough flying to qualify for his commission, and Pershing forwarded the recommendation in a cable dated February 26, 1918; the confirming cablegram announcing his appointment as a first lieutenant is dated March 11, 1918.11 Deetjen reports meeting Chalaire briefly in London in mid-April, and Milnor met him there at least twice in the first part of June.12

Chalaire was assigned on June 12, 1918, to No. 202 Squadron R.A.F., which was stationed at Bergues, about five miles south-southeast of Dunkirk.13 202 had been No. 2 Squadron Royal Naval Air Service prior to the amalgamation of the R.F.C. and the R.N.A.S. on April 1, 1918. Since March of 1917, the squadron had been flying DH.4s, two-seater aircraft used for long-range reconnaissance and bombing.14 Trevor Henshaw summarized the work of the squadron as follows: “In early 1918 the unit had been providing co-operation with the [British] naval operations for the blocking of [German held] Zeebrugge and Ostend on the Belgian coast. Photography, escort work and artillery spotting occupied them during the summer and into the autumn, during the advances of the Allies, and they assisted in this way in the eventual removal of German forces from the coastal areas.”15

About a month and a half after joining No. 202 Squadron, on the morning of July 29, 1918, Chalaire was flying was flying DH.4 D8402 on an escort and reconnaissance mission when he encountered eight enemy aircraft over German-occupied Tervaete; he and his gunner, Albert Edward Humphrey, were able to shoot two of them down out of control, but both Chalaire and Humphrey were wounded and forced to land at Rousbrugge (Roesbrugge, a village a few miles northwest of Poperinghe) just inside allied territory.16

Harold E. Bechtol, European manager of the Newspaper Enterprise Association, interviewed Chalaire about the incident. Bechtol reported that a “reconnaissance machine was sent to see whether the Germans were trying to put bridges across the Yser canal. Humphrey and Chalaire were sent in a two-seater as escort.” Bechtol then supplies the account he took down from Chalaire:

Just as the fellows in the observation machine had finished their work, five Hun planes bobbed up. We signalled for our other machine to beat it, and we hung back to keep the Huns from following. We were just “cold meat” for those five Huns–or so we thought. Three climbed above us and two got just below our tail, where Humphrey couldn’t get a shot at them. Humphrey kept put-put-putting at the Huns above, and he must have winged one. Because suddenly one came shooting down right ahead of me. Almost level with my gun he flattened out. There was nothing to do but let him have it, and down he went. I couldn’t have missed him. Then a broken clip jammed Humphrey’s gun, and those Germans under our tail were getting on my nerves. I flopped over to the left and on one side, and opened up. It was just luck–but I pinked one of them and he crashed down. That left three.

Then three more came up. I looked around at Humphrey. He had been hit several times–he got eight bullets in all. But there he was, with a Lewis gun on his shoulder, firing away. As I turned a bullet hit the rim of my goggles, but it was a glancing blow. Some luck–what? I jiggled the bar a minute, then dropped in a spin about 500 feet. This gave Humphrey a chance to shoot at the whole bunch. Then I noticed that the engine was going badly. The tank was empty. I tried the gravity [reserve tank]. It was still working, thank heaven. The Germans had dropped below our tail again, so I took another spin down. We went so low that about one more flop would have landed us on the ground. Then, just as we started to climb again, the Huns turned and beat it back. We were nearing the line and they got cold feet, I guess. We came on in and went to the hospital.17

Chalaire was initially admitted to 44 Casualty Clearing Station at Bergues and eventually to U.S. Army Base Hospital No. 37 in Dartford, Kent, England, where the interview with Bechtol presumably took place.18 News of his injury was passed along; the August 14, 1918, entry in War Birds includes the remark “I heard that Walter Chalaire got shot in the leg on a D.H. 4.” His gunner, Humphrey (also admitted to No. 44 C.C.S. before being evacuated to England), was awarded the Distinguished Flying Medal in September of 1918.19 The citation reads:

Aerial Gunner A. E. Humphrey has made 23 trips of 40 hours all told over enemy territory, and has proved himself a capable, cool and resourceful Gunlayer, in particular on 29 July 1918, when escorting a special and important reconnaissance over the Yser River. His machine was attacked by eight enemy aircraft and, after firing several rounds his gun jammed, so he immediately picked up his spare gun and, firing from the shoulder, brought one enemy aircraft down and continued firing on the others until he was severely wounded. His pilot spoke very highly of his conduct during the engagement.

Milnor, who had visited Chalaire at in hospital Dartford in mid-August, wrote in his diary on September 11, 1918, that “[John Warren] Leach and Chalaire came into the office [in London] after lunch. Both are doing very well.”

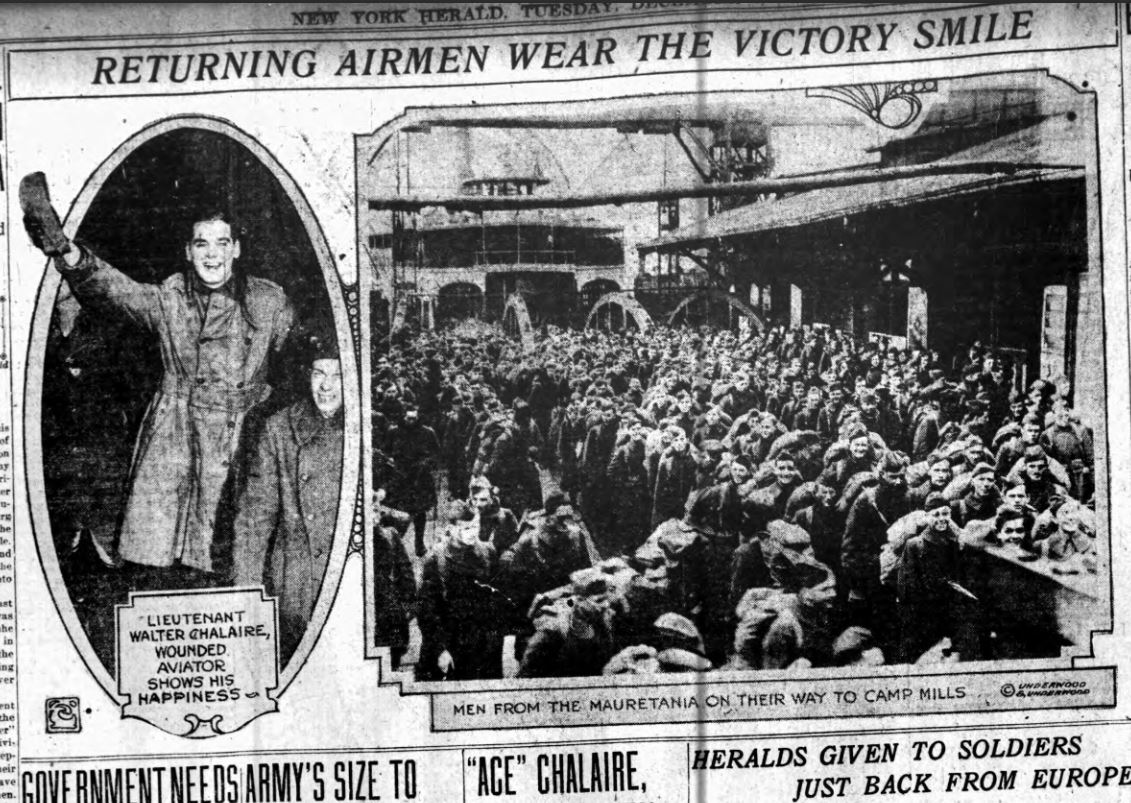

Chalaire returned to the U.S. on the Mauretania, departing Liverpool on November 25, 1918, and arriving at New York on December 2, 1918.20 Other “casual officers air service” on board included second Oxford detachment members Robert Alexander Anderson, Bonham Hagood Bostick, Raphael Sergius De Mitkiewicz, Alfred August Gaipa, Bradley Cleaver Lawton, Joseph Kirkbride Milnor, Douglas Hersey Mudge, Francis Kinloch Read, Homer Ireland Smith, and Lynn Lemuel Stratton. When Chalaire was discharged on April 9, 1919, he was described as ten percent disabled.21

Chalaire became an international corporation and estate lawyer. “Beginning in 1919 [he] practiced law with Sullivan & Cromwell and spent two and a half years in the Philippines for the firm. Later, he was a partner in Chalaire, Franklin in Shanghai. He returned to Sullivan & Cromwell in New York in 1927. From 1935 to 1958 he was a partner in Scadrett, Tuttle & Chalaire.”22

mrsmcq May 25, 2017; updated August 20, 2020, to reflect Milnor’s diary

Notes

(For complete bibliographic entries, please consult the list of works and web pages cited.)

1 Chalaire’s date and place of birth are taken from Ancestry.com, U.S., World War I Draft Registration Cards, 1917-1918, record for Walter Chalaire. The date and place of his death are taken from “Walter Chalaire, Lawyer, Dies.” The photo is a detail from a photo of Chalaire, Bulkley, and an unidentified cadet.

2 See Ancestry.com, 1900 United States Federal Census, record for Walter Chalaire; and Ancestry.com, New York, State Census, 1915, record for Alcied [sic] Chalaire.

3 See High School of Commerce, New York. Yearbook: Decennial Number 1912, p. 77.

4 See “Walter Chalaire, Lawyer, Dies.”

4a “Twenty-five Plattsburg Men to Become Aviators”; “Ground School Graduations [for August 25, 1917].”

5 The National Archives (United Kingdom), Royal Air Force officers’ service records 1918-1919, record for Walter Chalaire.

6 Chalaire, “Thanksgiving Day with the Aviators Abroad.” It seems likely that the article appeared in the New York Herald, for which Chalaire had worked, but I have not been able to confirm this.

7 Deetjen, Diary, entry for January 18, 1918.

8 See “Wedding.” I have not discovered what connection there was between Chalaire and the groom.

9 Deetjen, Diary, entry for February 17, 1918. “Straf” presumably means punishment (from German “strafen”).

10 Deetjen, Diary, entry for February 19, 1918.

11 See cablegram 652-S, and cablegram 900-R, p. 3 (an addendum to a cablegram dated March 9, 1918).

12 Deetjen, Diary, entry for April 17, 1918; Milnor, Diary, entries for June 5 and 8, 1918.

13 Sloan, Wings of Honor, p. 219; on the squadron’s location, see Philpott, The Birth of the Royal Air Force, p. 432.

14 Philpott, The Birth of the Royal Air Force, p. 432, lists the aircraft flown by the squadron.

15 “202 Squadron.”

16 See the entry in Henshaw, The Sky Their Battlefield II, and “Chalaire, W.”

17 Bechtol, “One Yankee Aviator Whips 8 Hun Planes in Crippled Machine.”

18 Chalaire’s RAF service record (see above) supplies “44 C.C.S.” MacPherson, Medical Services, pp. 266–67, establishes that 44 C.C.S. was at Bergues; the location has been sometimes misunderstood and/or mistranscribed as “Berque” or “Berques.” Bechtol indicates Chalaire was “in the American army hospital at Dartford”; Ford, Administration American Expeditionary Forces, p. 664, indicates this was Base Hospital No. 37.

19 The citation transcribed here is from an auction catalogue description for the medal; see “A fine Great War D.F.M. . . ,” which also provides some biographical information for Humphrey, including his admission to No. 44 C.C.S. It provides slightly more detail than the citation recorded in the Supplement to the London Gazette (“Awarded the Distinguished Flying Medal,” p. 11257).

20 Ancestry.com, U.S., Army Transport Service, Passenger Lists, 1910-1939, record for Walter Chalaire.

21 Ancestry.com, New York, Abstracts of World War I Military Service, 1917–1919, record for Walter Chalaire.

22 “Walter Chalaire, Lawyer, Dies.”