(Mifflintown, Pennsylvania, February 2, 1896 – Harrisburg, Pennsylvania, August 2, 1962).1

Princeton ✯ Oxford ✯ Stamford ✯ Feltwell, Harling Road, Sedgeford, Marske ✯ Issoudun, Tours, 50th Aero

Neely’s ancestors on both his father’s and his mother’s sides had resided and farmed in central Pennsylvania since emigrating from Ireland and Scotland in Colonial times. Some in Neely’s parents’ generation broke with the farming tradition and attended university. Neely’s father, John Howard Neely, and one of his maternal uncles, Andrew Banks, studied at Princeton; both pursued careers as lawyers.2 John Howard Neely married Ella Kate Banks in 1891; they had six children. William Hamlin Neely was the third child and third of three sons (the oldest son died in infancy).3

Princeton

Neely attended Harrisburg Academy, a private college preparatory school, before entering Princeton in the fall of 1913.4 His course work prepared him to go on to law school. His brother, John Howard Neely, Jr., who graduated from Princeton a year ahead of him, was working on his law degree at the University of Pennsylvania when Neely started his senior year in the autumn of 1916, and Neely intended to follow his lead. However, on February 3, 1917, the day after Neely turned twenty-one, the U.S. cut diplomatic relations with Germany, and the future began to look less certain. Neely closed his diary entry that day by remarking that “Maybe this diary will be finished in the trenches.”5

A “Princeton Provisional Battalion” was soon organized by the university for the training of military officers.6 Neely noted on February 26, 1917, that “Drill started today. My hour is 7:30 to 8:30 in the morning.” Around the same time, Neely began to consult with his family about going into aviation and was soon asking for and obtaining letters of recommendation from Princeton faculty members in support of his application. “I understand that applications are coming into Minneola [sic] at the rate of twenty per day. This means that they are going to be pretty strict on the examinations. I surely do hope that I get by, for it will be a wonderful training.”7

Meanwhile, a committee had been appointed at Princeton to look into “the feasibility of having a government aviation camp established at Princeton,”8 and on April 12, 1917, Neely learned from his friend Walter Melville Boadway that “there would be a flying unit here of 30 men, with two machines, by the first of May. I want to get in it if I can.” This again warranted consultation with his parents: “If I am admitted I will have to give up all classes and devote the entire day to that branch of the service.”9 Having received his parents’ blessing—though with some concern that he make sure he would receive his diploma—Neely handed in his application for the Princeton Aviation School to Professor Joseph Raycroft of the School’s faculty board on April 18, 1917, and took his preliminary examination for it the next day.

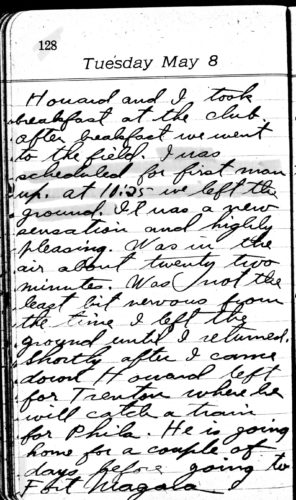

Ten days later his eyes were examined and his equilibrium tested: “they put me on a stool and spun me around ten times, then asked me to look at the doc’s fingers which were off in the opposite direction from what I was spinning.”10 On May 2, 1917, he got his physical and was “found O.K. in everything. . . . I understand that Kenneson has the arbitrary power to choose whoever he wants to be taken onto the squad. I surely do want to do this. I don’t know when I have ever wanted to do anything quite so much.” Edward Ralph Kenneson had been assigned as chief instructor at the Princeton Aviation School and oversaw much of the initial organization and construction.11 On May 3, 1917, having learned that he had passed the exam, Neely was sure that he would be accepted. He doesn’t mention his official acceptance in his diary, but on May 8, 1917, he was taken up on his first flight in one of the school’s Curtiss JN-4s (“Jennies”): “It was a new sensation and highly pleasing. Was in the air about twenty two minutes. Was not in the least bit nervous from the time I left the ground until I returned.”

Neely continued to hedge his bets by moving forward with his application to “the government school,” meaning presumably the Aviation Section of the Signal Corps and thus one of the recently established Schools of Military Aeronautics: “I think I shall take the exam and afterwards decide where to stay.”12 Six days later (May 15, 1917) Neely went “to see Mr. Mills and he told me they would hold my place open here until I decided what I wanted to do” (this was probably Marshall Freeborn Mills, who had helped set up the Princeton Aviation School). Neely went to Philadelphia on May 16, 1917, and “Took the exam . . . and passed it all right. However I have decided to remain in Princeton. I think I will learn a great deal more by staying here. Also will learn much more quickly. At the government schools they send you up to Cornell or Boston Tech for six weeks to get theoretical junk. By the end of that time if I stay here I think I will have gotten almost enough minutes to know how to fly.”

As a result of this decision, Neely did, indeed, get a good deal of experience flying. After his first flight on May 8, 1917, he went up with Princeton Aviation School instructor Frank Ralph Stanton on May 11, 1917, and then flew with an instructor at least twenty-five more times over the course of May and June 1917. His progress was uneven, and on one day he found he “couldn’t even keep the machine level and this is one of the most elementary things one learns,” but a few days later he was practicing landings: “They don’t seem very difficult.”13 He had a particularly tough time on the last day of May, nearly nose-diving into the ground instead of landing smoothly. “When we got back to the field [Stanton] lit into me.” Neely’s landings quickly improved, but two weeks later Stanton apparently still had reservations about him: “Stanton gave most of his men the back seat to-day. However I was not one of the lucky guys.”14 Neely notes making five more flights after this, but does not say whether he was ever given the instructor’s seat.

By the end of May 1917 it was evident that the U.S. government would establish a School of Military Aeronautics at Princeton—which had been left off the initial list of six such schools (which included Cornell and Neely’s “Boston Tech,” i.e., M.I.T.).15 The Princeton “ground school” would be an official training site for men accepted into the Aviation Section of the Signal Corps, and thus for many students like Neely who had flown at the privately funded and operated Princeton Aviation School.

Neely attended Princeton’s graduation ceremonies the weekend of June 16 and 17, 1917, and then went home to Mifflin for a week. He arrived back at Princeton on June 25, 1917, only to find that ground school—which he called “theoretical school”—would not start for another week, “much to my disgust.” This meant he was able to make a few more flights and also to have a few more days at home before being summoned to campus on July 5, 1917, by a telegram announcing that “the theoretical school was about to start.”

Two days later, Neely, now rooming with Frank William Sidler and Frank John Newbury, who had also been students at the Princeton Aviation School, wrote in his diary: “Very hard day’s work. Four hours drill, two buzzer, 40 minute calisthenics, one military law. Reveille 5:30, taps 9:30.” His August 25, 1917, graduation from ground school and inclusion in what would come to be known as the second Oxford detachment are proof that he did well—despite demerits for things like answering roll call by saying “Neely” instead of “‘Private Neely’ with emphasis on the private”—but he clearly found the “theoretical school” work much less engaging than actual flight training.16 He made a conscious decision not to keep up his diary through the summer, “for the work is routine & pretty much the same throughout the course.”17

Government flight training facilities in the U.S. existed at this time mostly on paper, and offers from the Allies to train American pilots were welcomed. According to a classmate of Neely’s, Arthur Richmond Taber, “a notice was posted on the bulletin board” some time in mid-August “saying that all men who wished to go to Italy for their flying instruction were to sign below.”18 Neely, along with about half of his Princeton ground school class, put his name on the list and was accepted for Italy. (His classmate and good friend Newbury was “detailed to France . . . I wish I could go with him.”19) Ordered to Mineola on August 27, 1917, the Italy-bound group spent three weeks hurrying up and waiting in and around New York. Finally, on September 18, 1917, they boarded the Carmania—a Cunard line ship being used to transport troops—and set sail. “Boat left about noon. Have three good bunk mates. One is [Joseph Frederick] Stillman, old Yale end”; the other two were Dudley Hersey Mudge and Joseph Kirkbride Milnor, who had both gone through ground school at Ohio State University. The detachment travelled first class, and the four men were assigned to an outside stateroom, C.47.20

The Carmania sailed initially to Halifax, Nova Scotia, where she arrived the morning of September 20, 1917. Late the next afternoon, as part of a convoy, the Carmania began the Atlantic crossing. Soon rough seas meant that those who were susceptible to it, including Neely, fell prey to sea sickness: “I have been feeling wobbly all day. You get what is known as a Coney Island drunk.”21 This seems to have worn off by the 28th, when men from the detachment were required to stand submarine watch; the next day Neely shared this duty with Mudge—a day also marked by the appearance of a number of destroyers sent out to guard the ships of the convoy as they approached the dangerous waters off the coast.

Oxford

On October 2, 1917, “when I awoke this morning I found myself in Liverpool.” There the men of the detachment learned that, while the enlisted men on board were proceeding to the continent, they themselves were to remain in England and attend ground school (again) at Oxford University. “The orders were mixed up & it now seems that we are not going to Italy. . . . Although I should prefer Italy, I know I shall enjoy England.”22 The men boarded a train for Oxford; Neely spent his first night in Exeter College, but the next day was moved, along with more than half the men in the detachment, to Christ Church College. “I am now living with Walter Knox and Bob [George Augustus] Vaughn”—both of whom had been at Princeton with him. “We have a top floor room, looking out on the quadrangle.”23

Their first full day at Oxford being a Wednesday, and classes commencing on Mondays, the detachment members had several free days before beginning their course at the Royal Flying Corps’s No. 2 School of Military Aeronautics at the university. On Thursday “Walter Knox, Ed Keenan, Frank Dixon and myself continued our tour of the university”—all of them had been at Princeton, the Aviation School, and ground school together. Neely was favorably impressed by the architecture he saw at Oxford University, a model for Princeton’s. After drill and inspection on Friday (“our detachment can’t hold a candle to the English cadets in drill”), Neely “took a walk down by the Thames with Walter Knox.” He was glad the next day to hear that “we will only be kept three weeks [at Oxford] if we can pass the examinations.”

Classes began Monday October 8, 1917, and Neely had “Rigging, aerial observation, engines and bombs,” as well as a lecture “by the head of the engine department.” The next day there was again aerial observation, but also “wireless, Clerget rotary engine, machine gun and a general lecture,” which consisted of “an outline of the flying in France.” Wednesday brought compass and map, and a general lecture by the head of the gunnery department on “the importance of understanding the gun thoroughly, so that you yourself could look it over before going up into the air.” After this, Neely began to find this second edition of ground school monotonous, although “not as bad as it was at Princeton,” mainly because the instructors were more experienced, many of them having flown on active service.24

On the free half day on Saturday, October 13, 1917, Neely went with Keenan and Dixon to watch a game of rugger, and the next day, with Dixon, he took “a canoe trip up Mesopotamia river”—I assume Neely thought the island in the Cherwell gave its name to the river. These excursions were undertaken despite dismal English autumn weather. Monday, October 15, 1917, “was a unique day. It was the first day it did not rain during our two weeks stay in Oxford.” Neely continued hopeful that exams in the third week would bring his time at Oxford to a close. At the beginning of that third week, however, he was preoccupied with moving “from our quarters in Christ Church to Exeter College. We have had a rather disagreeable time of moving. The day was rainy and we had to stand in formation in the rain, then chase up & down hunting our baggage by search light & cart it up two flights of stairs. . . . My room-mates are now Walter Knox and Howard Raftery.”25 The reason for the move, unmentioned by Neely, forms the substance of the diary entry for October 22, 1917, in War Birds. Cadets of both the first Oxford detachment (fifty Americans who had arrived in early September) and the second had held well-lubricated parties the previous evening and gotten cross-wise with the Commandant of the S.M.A. In addition to a thorough dressing-down, it was determined that all the American cadets should be segregated into one college, Exeter. Thus Neely ended up in a small room with the two others and “absolutely no room to put all your stuff away.”

On Wednesday, October 24, 1917, some of the cadets were taken out to a machine gun range “sunk down in an old quarry,” and Neely “got a fairly good shoot” on a Vickers gun. Two days later he received 265 out of 300 on a machine gun test and thought he “Should have done better.” The test was thought to be one of the exams that meant “we are going to get out very soon. Elliot [sic] Springs says the flying men will be posted first. I hope I get out soon & get thru flying school. The sooner you get to the front the better chance you will have of getting a higher commission out of it.”26 Neely also noted a few days later that he had “not been in a plane since June, and am getting anxious to get back into the old ozone once more.”27

On his fourth weekend in Oxford, Neely took part in a soccer match between the Americans of Exeter and the English of Jesus College—an uneven contest, given that “none of our men had ever played the game before.” “In return for playing soccer, Elliot gave me a pass,” which meant he and Knox could go to the movies.28 The next day, Sunday, he joined Knox and Dixon for a bike ride to Abingdon, south of Oxford: “very amusing” until Knox and Dixon “imbibed quite heavily” and a sober Neely abandoned them to their hilarity.

Finally, on the first day of November, “We learned . . . the men who are going to go to flying school. I am one of the twenty. We go to Stamford, Lincolnshire. Of the Princeton bunch, Frank Sidler, Bob Vaughn, Ed Cronin, Bostwick [sic; sc. Bonham Hagood Bostick], Newt Bevin, Harold Bulkley, Elliot Springs and myself go to flying squadron. Walter Knox, Ed Keenan, Howard Raftery, and Paul Carpenter will go to Grantham and take up gunnery. I rather hate to part with them, especially Walter Knox. We have bummed around quite a bit together.”29 At Stamford the twenty men from the second Oxford detachment would be joining men from the first Oxford detachment who had started flying training there about two weeks previously.

Stamford

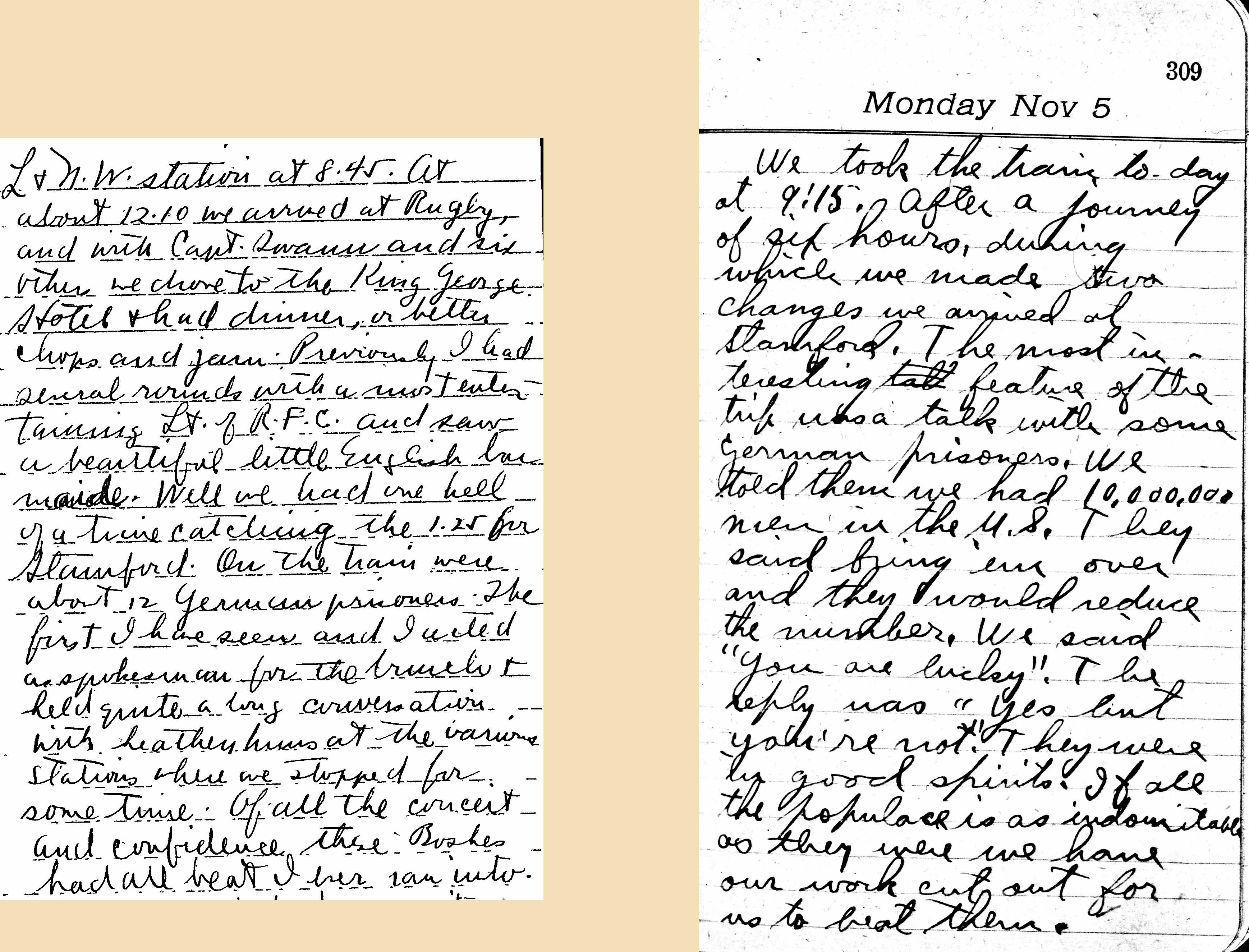

On November 3, 1917, Neely “got up in time to bid the boys good-bye. Went down to the station to see them off” to Grantham and machine gun school. The next day, a Sunday, he and Bostick rode bikes out to Woodstock and “went through the Duke of Marlborough’s park” at Blenheim before returning to Exeter College to pack. The six-hour train journey via Rugby to Stamford on November 5, 1917, was memorable for an encounter with some German prisoners. Neely’s fellow detachment member, William Ludwig Deetjen, spoke German and was able to interpret.30 Neely noted in his diary that the prisoners “were in good spirits. If all the populace is as indomitable as they were we have our work cut out for us to beat them.”

As luck and English weather would have it, Neely’s first twelve days at Stamford and No. 1 Training Depot Station at the air field south of the town were frustratingly flightless. On November 6, 1917, “In the afternoon we took the lorry and went out to the field. I didn’t get a flight due to the fact that the instructor who took Elliot Springs with him crashed up and flying was off for the rest of the afternoon.”31 The next day was one of the field’s alternating Wednesdays off—Neely occupied himself by taking a walk with Sidler and changing rooms in the house where the men quartered. The men who, like Deetjen, were scheduled for morning flying, got in some time in the air on Thursday before the weather closed in. The next day, November 9, 1917, Neely wrote that “I go on morning flying next week. The weather will then probably switch around.” And, indeed, he appears not to have flown until the end of his second week at No. 1 T.D.S.

Otherwise, the event of that second week at Stamford was another change of quarters. (Neely’s diary entries become increasingly sporadic after he arrived at Stamford, so information about him is largely second hand.) The “vacant private house,” “supposed to be a haunted one,” where the men were initially quartered (Deetjen gives the address “60 St. Martin’s Road”), was cold and the plumbing defective.32 In response to complaints the men were moved the evening of November 12, 1917, to the workhouse, literally.33 Vaughn remarked that “The place is not half so bad as the name would indicate, on the contrary we like it quite well, except for the fact that it is ten minutes walk to town.”34 Taber noted, with slight exaggeration, that 1 T.D.S. “Is near the sea coast” and thus potentially in the flight path of German bombers; night-time blackout was required.35 At least twice, according to Deetjen, police found that light could be seen coming from the workhouse building; the second time, “‘Cop’ came out tonight again & raised hell. . . . because our lights shone & he took Bill Neeley’s [sic] name, and not mine. Why he picked on Bill I don’t know.”36

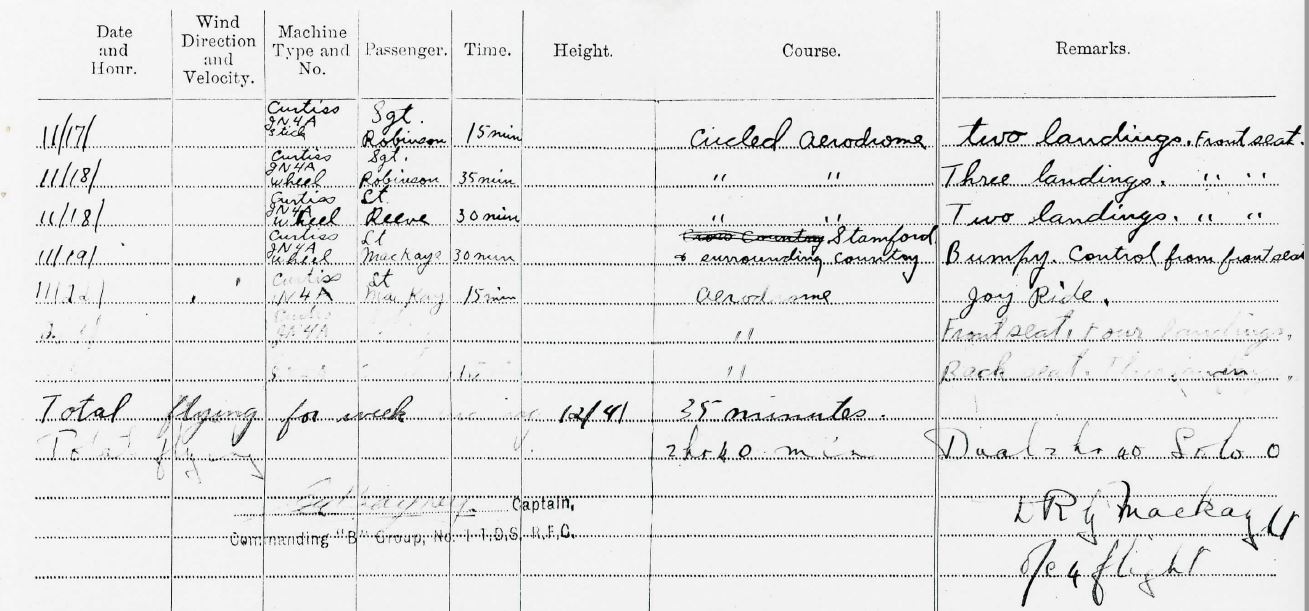

By this time, however, Neely was finally flying again and was perhaps not too bothered by the reprimand. On November 17, 1917, according to his Pilot’s Flying Log Book, he went up for fifteen minutes, still in the front seat, and circled the aerodrome. Neely’s records of his flight that day and those on the next two days are of interest because he notes flying JN-4A’s with both stick and wheel controls. The JN-4B’s at Princeton had had the older Deperdussin wheel controls.37 It was on a Jenny with a “Dep. control” that the plane in which Springs was a passenger at Stamford on November 6, 1917, had come to grief—the English pilot being accustomed to the stick control that was by then in much wider use.38 Taber wrote of flying at Stamford that “The different types of control are confusing,” and that switching between them was “like changing from a saddle-horse which is bridle-wise to one which is not.”39

Neely got in one more flight during November, on the 22nd, a “joy ride” with Duncan Ronald Gordon MacKay, the officer in charge of no. 4 flight at Stamford. After this, the weather was, according to Vaughn, “pretty bad for flying.”40 The day before Thanksgiving, Neely, Deetjen, Sidler, and Raymond Watts “went thru the Blackstone Co’s shell plant here in town.”41 Blackstone and Company had been founded as a maker of farm implements, but was evidently at this time part of the war effort. “Most all of the machine shop labor has been replaced by girls. They all wear blue jumpers and we saw them turning out 18 lb. and 6 inch shells.”42 In the evening Neely and Deetjen went to the movies. Neely wrote the next day that “I went down to Grantham and had Thanksgiving dinner with the original detachment. It was a mighty good dinner but the fellows ran it out entirely too much,” or as Deetjen put it: “after the dinner – oh! I won’t describe it, but take it from me ’twas the wildest party I ever attended.”43

Neely apparently got in two more flights on December 4, 1917 (“apparently” because his log book is hard to read), finally flying in the back seat. Two days later he flew solo—an event noted in his much neglected diary: “As I was taxying into the hangars the sergeant nodded his approval of the show, so I felt as tho’ I had gotten away with it all right. It surely did feel good to get up in the air alone and feel that you were your own boss.”

Over the next five days, when weather was decent, Neely was able to get in another five solo flights, one lasting seventy minutes. His second flight on December 11, 1917, left him shaken and berating himself. “At the end of my afternoon flight I came to grief, in the form of my first crack up. . . . Just before I would have hit the ground I saw a machine directly under me. It was too late to do anything. In fact I was then finally leveling off for my landing. Almost the same instant that I saw the edge of the plane on the ground I hit plump on top of it. I quickly shut off my switch. But Gregg—the fellow in the lower plane, must have put on throttle, for he started across the field with me on top.” Neely got to the ground and “went around to the right hand side and shut off the motor. [Gregg] could not reach it. The undercarriage of my plane was in his way.” Neither Neely nor Gregg (probably David Gregg of the first Oxford detachment) was injured. “They say everyone must have a crash. Maybe so, but this one was avoidable. If I had looked carefully over the aerodrome I would not have landed.” Neely’s mishap was not unique that day: Deetjen wrote that “Out on the patch—there at the field—you’ll find a bunch of rubbish. Quite a bunch at that, for seven more crashed today. In fact we all have our ‘wind up’ to a great degree. Twice a landing buss crashed onto one on the ground. In neither case were there any injuries. Bill Neeley just crawled out on top of Gregg, both in Curtiss planes. [Daniel] Waters broke his twice. . . . We can thank our Maker that no one has been killed. There have been far too many bad accidents with simply miraculous escapes. If this luck follows us to France, we will be world beaters.”

Their luck gave out before they crossed the channel. Neely’s next (and antepenultimate) diary entry records the death of Harold Ainsworth of the first Oxford detachment on December 19, 1917: “killed while stunting a Curtiss plane. He was doing a loop when the wing came off. He plunged headlong to the ground. This is the result of the order which makes us stunt these old Curtisses. It is an order given by somebody that either knows nothing about conditions or else by a man who doesn’t care whether any of these men come through or not. These machines are as old as the hills & most of them should be condemned for straight flying let alone stunting.” Similar accounts of Ainsworth’s accident and criticism of the authorities can be found in Deetjen’s diary for that day and in the War Birds entry for January 1, 1918.44

Neely records in his log book having gotten in fifty minutes solo flying on December 15, 1917. He describes in his diary in some detail his next, and final, two flights at Stamford on December 22, 1917 (the day of Ainsworth’s funeral): “In the morning I had up a JN3, a very old Curtiss type of pre-war design. It is a much harder machine than the A [presumably JN-4A] to fly, but is good practice as we will have to go on the planes of lighter control.” Later in the day, he took up JN-4A B1942: “I had a stick control & as I am not used to it it was rather difficult landing & taking off. I am going to use a stick however, from now on, because you have to fly that exclusively later.” His total flying time at Stamford was two hours and fifty-five minutes dual, and five hours fifty minutes solo, all, but for the one flight in a JN-3, on JN-4A’s.

Neely’s last, inauspicious, diary entry was written the next day, describing the collision of two DH-6s that killed George Longley Lewington and Stanley James Young.

Some of the men training at Stamford, like Deetjen and Springs, took advantage of Christmas leave to travel, but, according to Vaughn, “Most of us spent our Christmas right here in Stamford. . . . At night we had a Princeton dinner ordered at a little restaurant or tea room here, and all the Princeton fellows not on leave (10 in all) were there,” probably including Neely.

I am not aware of a journal kept by Neely in 1918, although that is not proof that such did not or does not exist. It is possible that Neely felt that his Pilot’s Flying Log Book alone provided an adequate record of his activities going forward. In any case, the log book and the summary of his service that Neely wrote for the Pennsylvania War History Commission are the sources for most of the sparse information about what he did after his time at Stamford in what follows.45 There are apparent date discrepancies between the two documents. I suspect that the dates Neely provided for the Pennsylvania War History Commission were based on memory and approximate; I have assumed that dates in the log book are accurate.

Feltwell, Harling Road, Sedgeford, Marske

Early in the new year Neely was posted to No. 7 Training Depot Station at Feltwell in Norfolk. There, on January 6, 1918, he made his first flight in an Avro, the ubiquitous R.F.C. training plane, as a passenger. The next day, and again on the twelfth and fifteenth, he went up with an instructor but controlled the plane from the rear seat. On January 21, 1918, he began flying solo again. Evidently winter weather was improving; No. 7 T.D.S. probably also had a better ratio of training planes to students than No. 1 T.D.S. at Stamford. Neely started piling on the hours. He began stunting (“loop, 3 spins, Immelmanns” on January 25, 1918), practicing vertical banks, and then did some formation flying. In early February Neely passed his height test (flying at 9,000 feet), and in mid-February he made a cross country flight: one hour and forty minutes to Harling Road air field at Roudham, fifteen miles to the east of Feltwell, and back, thus fulfilling another prerequisite for graduating from this stage of R.F.C. training. The next day, February 16, 1918, he completed a further requirement, flying an operational plane for the first time, a Sopwith Pup. That day he did only “straight flying,” but over the next few days, he practiced stunting and brought his total flying time (in England) up to just over thirty-seven hours, thirty of which were solo. His exact R.F.C. graduation date is not noted, but he made his last flight at No. 7 T.D.S. on February 19, 1918. Graduation entitled him to several days leave, which he took in London.46 He also qualified for his commission around this time; Pershing’s cablegram forwarding the recommendation is dated March 6, 1918.47

For the next stage of his training Neely was posted to Harling Road and No. 94 Squadron, a squadron at this time tasked with training pilots to fly Sopwith Camels. For his first flights at Harling Road at the end of February and the beginning of March, Neely once again flew an Avro (solo), but on March 6, 1918, he was back on Pups, flying nearly every day and, on March 19, 1918, he flew a Camel. During his second time in a Camel, on March 21, 1918, he had a bad landing, damaging both a tire and the propeller, but he went up in a Camel again on the next and subsequent days. In the meantime, Washington sent a cable dated March 10, 1918, that included approval of his commission; it apparently became official on March 22, 1918, and “Neeley” was placed on active service on March 28, 1918.48

In his log book’s remarks section, Neely noted of his final flight on a Camel at Harling Road on April 2, 1918: “Roll, engine cut out.” After this Neely had a nearly three week break from flying until April 22, 1918. According to his log book, he was posted to No. 110 Squadron at Sedgeford and was on that date flying an “A.W.”—presumably an Armstrong Whitworth FK.8.

This switch—from Camels to FK.8s—is unusual and drastic. Neely had spent three months training to be a fighter pilot and was now apparently destined for observation or bombing in two-seater aircraft. Without further information, one can only speculate on the logic, if any, for the reassignment. Possibly Neely was yanked off Camels because the U.S. Air Service anticipated the need for DH-4 pilots. Or, after having his engine cut out on him during his flight in early April, Neely may have chosen not to continue on Camels. Because of the torque of their rotary engines, Camels were notoriously tricky to fly, as attested by the large number of accidents associated with them in training (one of the second Oxford detachment men, when told he was to transfer to Camels, complained vociferously and was put back on S.E.5s49).

There is another puzzling bit of (mis)information related to Neely during this period. Deetjen, who knew Neely well from Stamford, wrote in his diary on March 28, 1918, that there was “a rumor that Bill Neely had gone west”; on April 2, 1918, Deetjen wrote that “Bill Neely did die at Ayre [sic]. He was rolling an S.E.5 and his wings came off.” There were a number of fatal flying accidents at Ayr in March 1918, including ones involving Thomas Sydney Ough Dealy and Harry Glenn Velie, either of whose last names could have been garbled as “Neely.”50 Dealy and Velie were both killed flying Camels, but Thomas Cushman Nathan of the first Oxford detachment was killed on an S.E.5 at Ayr on March 20, 1918, when one of his wings collapsed. Perhaps the details of Nathan’s accident were attached to Neely’s name. Nevertheless, Deetjen’s mistake was an odd one to make; that he did not later correct it may be an index of Neely’s isolation from others in the Oxford detachments while he was at Harling Road.

After four flights on an “A.W.” and one on a Martinsyde (probably a G100 or G102),51 Neely spent most of the rest of his time at Sedgeford flying DH.9s (planes based on and closely related to the DH.4); he practiced loops, aerial firing, and bombing. He last records a flight there on May 13, 1918, and notes a total of over seventy-seven hours flying. There are no log book entries for the second half of May 1918, perhaps reflecting his having been given some leave or perhaps ground course work.

Neely’s final training posting was to No. 2 Fighting School at Marske-by-the-Sea in North Yorkshire, a good 130 miles north of Norfolk where he had done most of his previous training.

At Marske, from June 3 through June 26, 1918, Neely made two flights in an Avro and then seven in a D.H.9, working on aerial fighting, firing, and formation flying. Neely’s log book, seems to break off at this point. Perhaps as a result of his transfer overseas in early July 1918, the subsequent entries were separated from his training log book and not passed on to family and researchers; perhaps once he was transferred to the A.E.F. he no longer kept up his R.F.C. issued book.

At Marske Neely would have crossed paths with a number of second Oxford detachment men, many of them training on scout machines, but also at least two who were, like him, training for observation and bombing: Allen Tracy Bird and Walter Ferguson Halley.52

Issoudun, Tours, 50th Aero

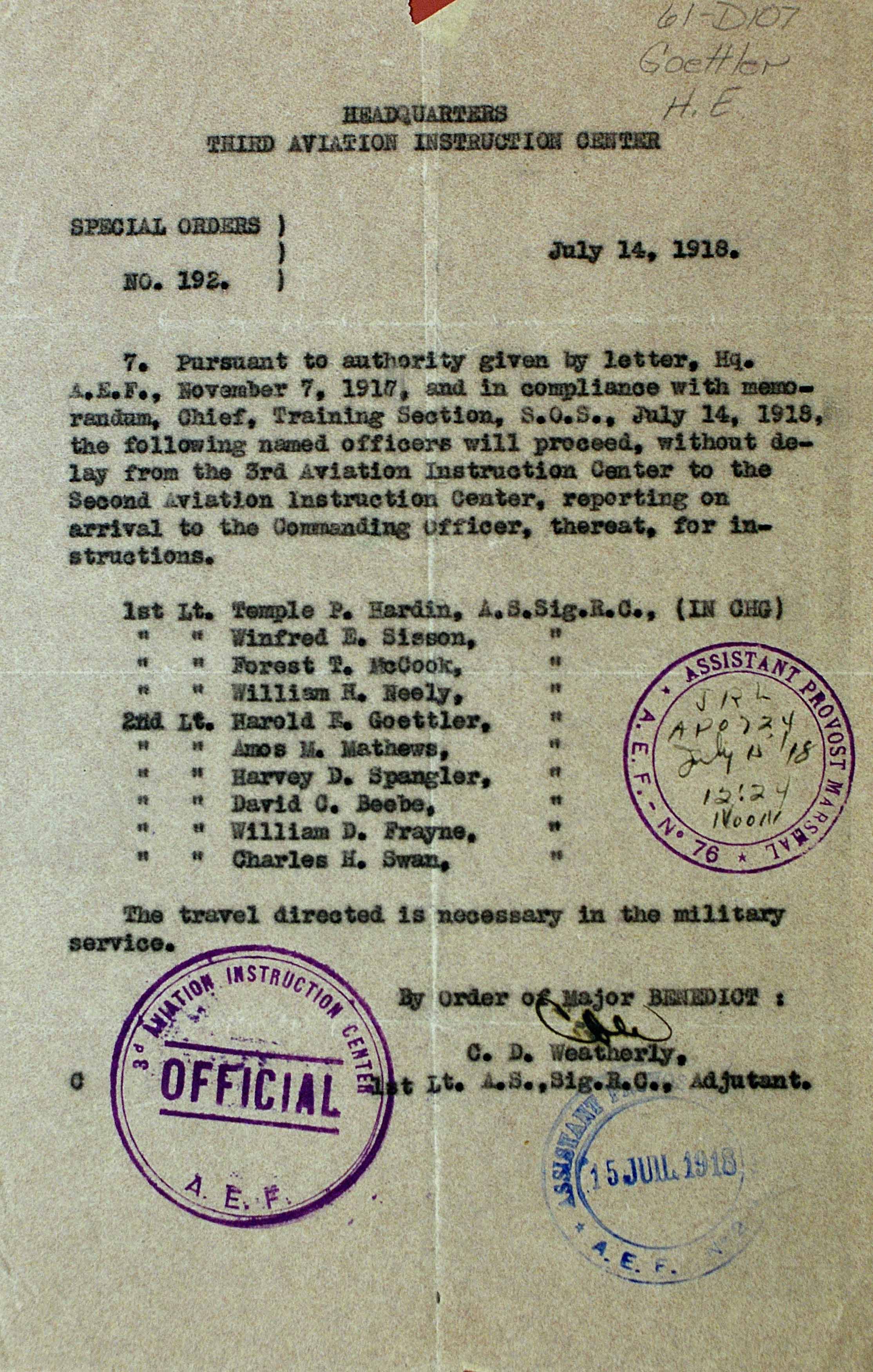

Bird and Halley, along with Harold Ernest Goettler and Claude Stokes Garrett, who had trained with the R.F.C. in Canada, were ordered to travel from Marske to London in early July, preparatory to going overseas, and it seems likely that Neely received similar orders around the same time.53 Neely is documented among a large group of men ordered on July 5, 1918, to travel from London to the 3rd Aviation Instruction Center at Issoudun in the Loire region of central France, and then in a group ordered on July 14, 1918, from Issoudun to the 2nd Aviation Instruction Center at Tours some seventy miles to the northwest of Issoudun.54

Goettler notes in his diary on July 19, 1918, that “[Paul Temple] Hardin, [Winfield Earl] Sisson, Neely and [Thomas Forrest] McCook received a little dual on the old French Breguets that are in camp.” Goettler himself was soon asked to serve as an instructor on Breguets at Tours. At some point a similar request was evidently made of Neely, whose account of his military service for the Pennsylvania War History Commission indicates that at 2nd A.I.C. he was “Chief Instructor on D.H.4’s.” While Goettler, Bird, McCook, and Hardin were posted to the U.S. 50th Aero Squadron in August, Neely remained at Tours until the first part of October 1918, when he also was also posted to the 50th Aero. In his account of his military service Neely gives October 10, 1918, as the start date for his time with the squadron. Daniel Parmelee Morse, the commanding officer and historian of the 50th Aero, writes that Neely was one of three pilots who reported for duty on October 13, 1918.55 Neither Neely nor Morse is entirely reliable when it comes to dates, but it seems reasonable that three days should have elapsed between the date of Neely’s assignment and his arrival at the 50th, which was located over two hundred miles to the east of Tours.

The 50th Aero was an observation squadron flying DH-4s.56 It had taken part in the St. Mihiel Offensive. Not long before the opening of the Meuse-Argonne Offensive on September 26, 1918, the 50th had, along with the 1st and 12th Observations Squadrons, moved to the 1st Corps Observation Group aerodrome near Remicourt at the western edge of the American First Army and about sixteen miles south of the front. The 50th was there initially tasked with supporting the 77th Infantry Division. By the time Neely was flying, the 77th had advanced a good ten miles north to the vicinity of Grandpré; the 50th subsequently cooperated with the 78th Infantry Division, which on October 15, 1918, relieved the 77th and continued the advance north.57

While Morse’s published history of the 50th Aero and the typescript “50th Aero Squadron, Historical Account,” evidently also written by him, note the number and nature of missions flown by the 50th during the period Neely was with the squadron, they seldom provide such details as the names of the men who flew them. One of the exceptions is Morses’ account of a reconnaissance mission flown on October 29, 1918 that included Neely. The squadron had the previous day relocated about thirteen miles to the northeast, so missions on the 29th were flown out of Clermont-en-Argonne. “German aerial activity was particularly marked, necessitating two protection ships to accompany each mission ship. In this manner two successful reconnaissance missions were carried to completion, although one mission formation was attacked by a large formation of Fokkers.”58 Morse goes on to record that the mission formation that was attacked consisted of planes piloted by Floyd Meredith Pickrell and Neely with their observers Mitchell Harvey Brown and Horace Osment respectively, along with their “protection ships.” Pickrell later recalled that

the most serious battle I had with enemy aircraft was on 29 October 1918 when Lt. Mitch Brown and myself were attacked by 18 planes. I was leading and Brown was my observer, and Lt. Bill Neely, . . . was flying the second plane. We were going over the front lines just before sundown, and they came at us out of the sun. We never saw them until they were right on us. My escort and I went into a tight circle to give the observers a chance to fire. Mitch saw them before I did. I was watching where we were going. Over here was Grandpré at the head of the Argonne Forest, . . . [Mitch] shot two of them off our tail and I saw them go down in a spin. Now, we couldn’t hang around to see whether or not they crashed, you know, we had other things to do. We asked for confirmation on those but we never got it. . . . Those were Fokker biplanes. They had red noses, every one of them. . . . they said it was [Richthofen’s] squadron. Neely and Osment also put in for confirmation for one of them but never got it.59

Morse provides a summary showing the number of missions and hours flown by each pilot and observer of the 50th Aero. Bird, who was with the squadron during both St. Mihiel and Meuse-Argonne, flew twenty missions and thirty-six hours. Neely’s total of ten missions and fifteen hours, compares favorably, given that he flew only during the Meuse-Argonne Offensive.60

Neely indicated in his own account of his military service that he served with the 50th Aero through mid-January 1919. He and fellow second Oxford detachment member Robert Arthur Kelly returned to the United States on the Roma, which left Marseille in mid-March 1919, arriving at New York on April 4, 1919.61 Neely settled in Harriburg and pursued his delayed career as a lawyer, eventually serving as a county court judge.62

mrsmcq November 16, 2020

Notes

(For complete bibliographic entries, please consult the list of works and web pages cited.)

1 For Neely’s place and date of birth, see Ancestry.com, U.S., World War I Draft Registration Cards, 1917–1918, record for William Hamlin Neely. For his place and date of death, see Ancestry.com, Pennsylvania, Death Certificates, 1906–1963, record for William H Neely. It should be noted that newspapers reported his death as having occurred on August 3, 1962; see, for example, “Judge Neely of Dauphin Dies at 66.” The photo is a detail from a photo of the Princeton School of Military Aeronautics ground school class that graduated August 25, 1917.

2 On John Howard Neely and his descent, see Commemorative Biographical Encylcopedia of the Juniata Valley, vol. 2, pp. 784–86. On the Banks family, see McAllister, The Descendants of John Thomson, pp. 107 ff.

3 On Neely’s immediate family, see documents available at Ancestry.com.

4 McAllister, The Descendants of John Thomson, p. 109.

5 Neely, diary, passim, and entry for February 3, 1917. Unless otherwise noted, the following account of Neely in 1917 is largely based on his diary; quotations from the diary are footnoted when the date of the entry might not otherwise be evident.

6 Hunt, Tomlinson, and Sheridan, “Timeline: Princeton in the Great War.”

7 Neely, diary entry for March 7, 1917.

8 Hunt, Tomlinson, and Sheridan, “Timeline: Princeton in the Great War.”

9 Neely, diary entry for April 13, 1917.

10 Neely, diary entry for April 29, 1917.

11 “Edward Ralph Kenneson.”

12 Neely, diary entry for May 9, 1917.

13 Neely, diary entries for May 21 and 29, 1917.

14 Neely, diary entry for June 12, 1917.

15 Hunt, Tomlinson, and Sheridan, “Timeline: Princeton in the Great War.

16 Neely, diary entry for July 12, 1917.

17 Neely, diary entry for July 19, 1917.

18 Taber, Arthur Richmond Taber, p. 70.

19 Neely, summary diary entry p. 250.

20 Milnor, diary entry for September 18, 1917, names all of the room mates and provides the room number.

21 Neely, diary entry for September 23, 1917.

22 Neely, diary entry for October 2, 1917.

23 Neely, diary entry for October 3, 1917.

24 Neely, diary entry for October 11, 1917.

25 Neely, diary entry for October 22, 1917.

26 Neely, diary entry for October 26, 1917.

27 Neely, diary entry for October 31, 1917.

28 Neely, diary entry for October 27, 1917.

29 Neely does not list Dixon and Arthur Taber, both of whom were Princeton S.M.A. graduates and among the twenty men who went to Stamford.

30 See Deetjen’s diary entry for November 5, 1917.

31 See Springs account of the incident in his letter of November 6, 1917, to his father on p. 49 of Springs, Letters from a War Bird.

32 Vaughn, War Flying in France, pp. 29 and 30; Deetjen, diary entries for November 7 and 13, 1917.

33 Deetjen, diary entry for November 13, 1917.

34 Vaughn, War Flying in France, p. 31. Whether this was the older work house on Barnack Road or the one on the Bourne Road, I have not been able to determine. Both Deetjen and Vaughn state that it was a half mile out of town, which would suggest it was the latter—although it seems odd that they would be placed in a still functioning institution, rather than in a building of the one that had been repurposed. See “Stamford, Lincolnshire.”

35 Taber, Arthur Richmond Taber, p. 93.

36 Deetjen, diary entry for November 18, 1917.

37 Mike O’Neal, personal communication.

38 Springs, Letters from a War Bird, p. 49 (Springs indicates the accident had taken place the previous day).

39 Taber, Arthur Richmond Taber, p. 96.

40 Vaughn, War Flying in France, p. 32.

41 Deetjen, diary entry for November 30, 1917.

42 Ibid.

43 Ibid.

44 See also Ogilvie, “Training Errors of the A.E.F”; Springs, Letters from a War Bird, p. 67; and Skelton, Lt. Henry R. Clay, pp. 7 and 19. Both Springs and Clay had apparently flown the plane, A1259, in which Ainsworth was killed, as had, according to War Birds, Lindley Haines DeGarmo (Clay and DeGarmo were in the first Oxford detachment).

45 Included in Ancestry.com, Pennsylvania, WWI Veterans Service and Compensation Files, 1917–1919, 1934–1948, record for William Hamlin Neely.

46 “Mifflintown Boy Graduates as Aviator in London Camp.”

47 Cablegram 657-S.

48 Cablegram 895-R; Neely’s account of his military service for the Pennsylvania War History Commission, included in Ancestry.com, Pennsylvania, WWI Veterans Service and Compensation Files, 1917–1919, 1934–1948, record for William Hamlin Neely; and McAndrew, “Special Orders No. 205.”

49 Barksdale, diary entries for June 22 and July 9, 1918.

50 See the commentary and notes to Parr Hooper’s letter of April 3, 1918, in Hooper, Somewhere in France, regarding some of the confusion surrounding these names.

51 Neely’s log book, unlike most of the others I have seen, does not record airplane serial numbers, so that one must speculate as to precisely which planes are meant by “A.W.” and “Martinsyde.”

52 Brown, Jesse Campbell, Curtis, Forster, Fulford, Wicks, and perhaps others were training on S.E.5s; Barksdale was also at Marske training on Avros and Pups.

53 Biddle, “Special Orders No. 109.”

54 [Biddle?], “Special Orders No. 109″; Benedict, “Special Orders No. 192”; see also Goettler, diary entries for July 3– 15, 1918.

55 Morse, The History of the 50th Aero Squadron, p. 54.

56 Conventionally, “DH.4″ refers to the British plane, “DH-4″ to the American-built version of the same plane.

57 Morse, The History of the 50th Aero Squadron, pp. 56 and 73; Historical Branch, War Plans Division, General Staff, Brief Histories of Divisions, U.S. Armies 1917–1918, p. 60.

58 Morse, The History of the 50th Aero Squadron, p. 59.

59 Ruffin, “Flying in France with the Fiftieth: 1/Lt. Floyd M. Pickrell, USAS,” p. 164.

60 Morse, The History of the 50th Aero Squadron, p. 83.

61 War Department. Office of the Quartermaster General, Army Transport Service, Lists of Incoming Passengers, 1917 – 1938, Passenger list for Casuals, on S. S. Roma.

62 “Judge Neely of Dauphin Dies at 66.”