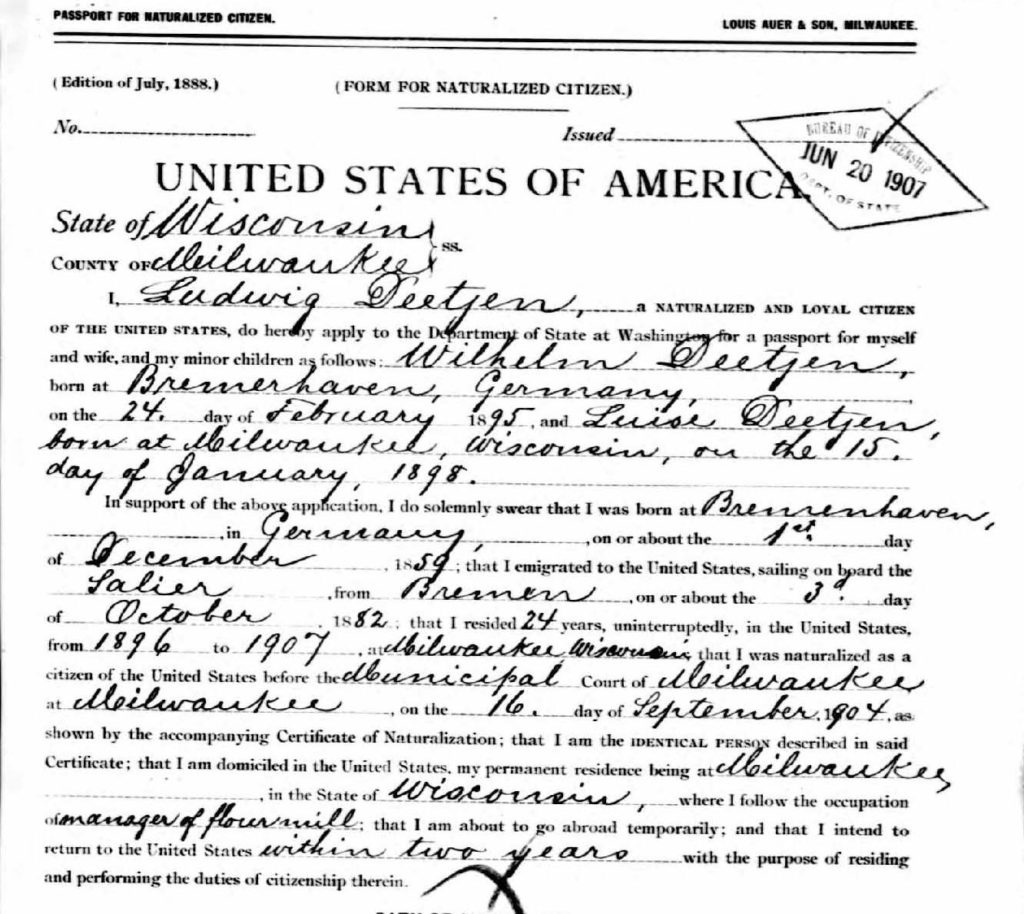

(Bremerhaven, Germany, February 24, 1895 – June 30, 1918, vicinity of Schirmeck, France).1

Prologue ✯ Oxford ✯ Stamford ✯ Waddington ✯ Marske-by-the-Sea ✯ Stonehenge ✯ No. 104 Squadron I.A.F. ✯ Epilogue

Prologue

Deetjen’s mother and father were from Bremerhaven; they had come to the US in 1887 and 1882, respectively, and married in Chicago in 1892.2

They were visiting Bremerhaven in 1895 when Deetjen was born, but soon returned to the United States. Deetjen senior was in the flour milling business, initially in Wisconsin, then in Pennsylvania.3 The family maintained contact with their relatives in Bremerhaven, and their daughter, Louise Adelheid Deetjen, was visiting the city when the war broke out, her parents having left Germany for New York earlier in the summer.4 William Ludwig Deetjen’s R.A.F. service record notes under “special qualifications”: “German (Verbal & Reading).”5

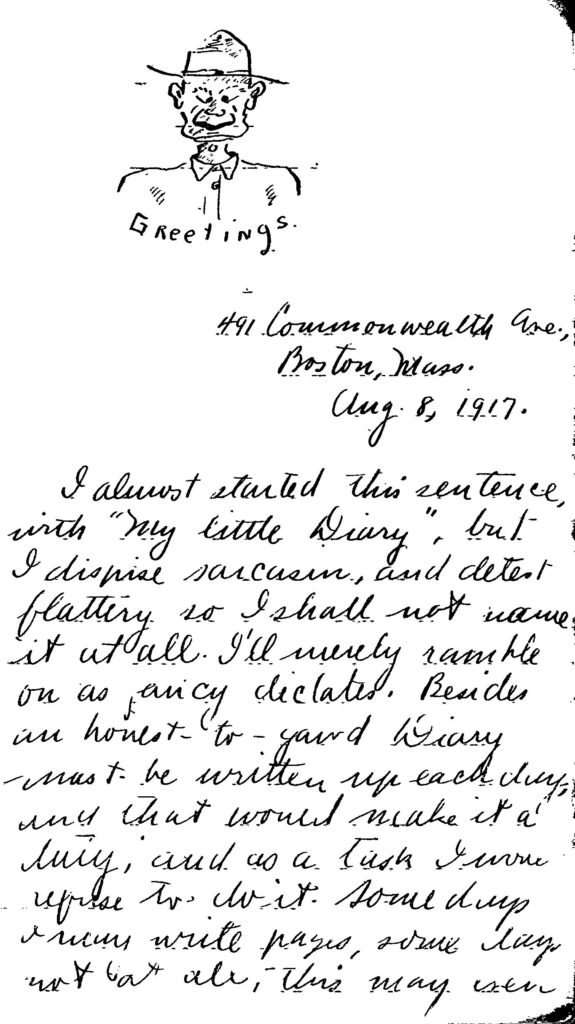

Deetjen trained at Staunton Military Academy in Virginia, graduating in 1913, and went on to the Wharton School at the University of Pennsylvania (class of 1917); it is not clear whether he graduated.6 In 1916–1917 he was employed by his father’s Manheim Milling Company based in Manheim, Pennsylvania; he lived in Montclair, New Jersey, and was a member of the New York Produce Exchange.7 Also during this period he served in Company A of the Montclair Battalion, a recently created paramilitary organization. Later, in the diary he began keeping in August 1917, he wrote that the “months I spent in Montclair will remain ever vivid with the loyalty that the men . . . of the Battalion gave me.”8

In early 1917 Deetjen applied for the Officers’ Reserve Corps; he was commissioned a second lieutenant in the infantry and reported to Plattsburg in May.9 He successfully applied for the Aviation Section of the Signal Corps and entered ground school at M.I.T. in June, graduating July 28, 1917, along with his friend Albert C. Rothwell and several others who became members of the first Oxford detachment; of this ground-school class , only Deetjen became a member of the second Oxford detachment.10 (Deetjen’s name appears, erroneously, on the M.I.T. ground school graduation list for August 25, 1917.11) Army red tape kept Deetjen in Boston through early September. Orders came through for Private Deetjen to sail for France, but couldn’t be acted on, as he was now a lieutenant. He ultimately went to Washington, D.C., and consulted with Hiram Bingham and others about his situation. He managed to get himself reduced back to a private, which allowed him to act on his orders to embark for Europe for flight training.

Deetjen reported to Mineola on September 12, 1917, “for Italian service,” and was fortunate enough while there to be taken up on a thirty-five minute flight by a “Lt. Salmon,” with a few minutes at the controls himself.12 When the 150 men of the “Italian” or “second Oxford detachment” left New York on September 18, 1917, to sail for England on the Carmania, Deetjen was appointed 2nd sergeant (Elliott White Springs was “top” sergeant).13 The ship made initially for Halifax to join a convoy for the Atlantic crossing. The convoy set out, with much patriotic fanfare, on September 21, 1917. Deetjen’s cabin mates on the voyage were Philip Dietz, Leonard Joseph Desson, and John Joseph Devery.14

Oxford

The Carmania docked at Liverpool on October 2, 1917.

“No sooner had we hit shore than we were informed orders were there that we were to train in English schools, and not go to Italy. This did not faze me (see section on Army orders) but made all the others feel ungodly blue. . . . And so we got aboard one of those little trains that might raise hell when they grow up to full size, and choo chooed down to Oxford (six hrs) where the good news (?) greeted us that we were slated for six weeks of ground school. Gloom prevailed, the detachment looked like it was going to drag their chins on the ground. We were split in two, lost our good old Major MacDill, who had tears in his eyes when he said goodbye, and I went to Queen’s College as 1st Sergt with 60 men. Springs went to Christ Church with 90.”15

Springs later recalled Deetjen as “my right hand man at Oxford.”16 Deetjen’s duties at Queen’s included drilling the sixty men, who were now labelled “B flight”—“A flight” being the men of the first Oxford detachment housed at Queen’s. Both flights reported to first Oxford detachment member Bennett Oliver. Paul Stuart Winslow, who had charge of A flight, wrote an extended diary entry on October 9, 1917, describing drilling the men and comparing American methods and English: “The flight commanders (Riety. [sic; sc. Deetjen] and I) line the men up, dress them, and report to Oliver. He then says ‘March off by flights — A flight leading,’ and I yell ‘A flight Right by Squads—March’ and off we go, and B flight does the same, and joins us out in the street. . . .”16a

Deetjen was delighted to find his ground school classmate Rothwell at Oxford. After settling in as comfortably as was possible in a room “small and cold, with a little fire place and no coal,” he set out with his roommate Donald Andrew Wilson to explore the town: “Crooked streets, ancient houses, and nothing but bloomin’ Virginia cigarettes. The monetary system is a Chinese puzzle and coupled with the bally Hinglish you can imagine the trouble I had. Gad, why don’t Englishmen speak English?”17

While at Oxford, Deetjen rowed on the Thames with a crew that included Joseph Frederick Stillman, Donald Swett Poler, Phillips Merrill Payson, and Donald Elsworth Carlton on one occasion; Payson, Harry Adam Schlotzhauer, Stillman, and Alexander Miguel Roberts on another.18 On a visit to the theater, he experienced his first air raid alert; the play went on by lantern and candle light.19 Other socializing included visits with Eugene Hoy Barksdale, Lloyd Andrews Hamilton, and Carlton to an otherwise unidentified American family named Morrison, whose invitation Deetjen accepted in preference to one from Sir William and Lady Osler.20

When, on October 20, 1917, the first Oxford detachment celebrated its graduation in such an exuberant fashion that they got very much on the wrong side of the commanding officer of the Oxford School of Military Aeronautics, Deetjen was enjoying a fairly decorous dinner at Buol’s with Conrad Henry Matthiessen, Joseph Ralph Sandford, and Payson. However, coincidentally, his roommate Wilson, along with Roberts and Poler, happened not to return to college that night and were thus absent when a roll call was ordered by the furious C.O. at 11:30 p.m. Deetjen did his best to cover for the three men in his charge by filching the slip of paper with their names on it, but ultimately to no avail. Fortunately, when he took them to the C.O., the latter “read them the riot act,” and that was all. But the events of October 20 prompted the C.O. to order all the Americans to move from Christ Church and Queen’s to Exeter. This was, if possible, a step down in comfort, but Deetjen was glad to have his dining companions from Buol’s as his new roommates.21

On November 3, 1917, Deetjen watched “129 of our outfit leave for Grantham Gunnery School.” The next day he and James Ernest Roth walked out to Wytham and stopped on the way back at Port Meadow aerodrome. He saw an Avro crash, fortunately without much injury to the pilot, and saw a Sopwith Pup take off: “The bloomin’ Pup just shot up with much climb even on turns. She is so wonderful, small & fast, that now I’m going to try and make a fighter or scout, instead of a bomber.”22

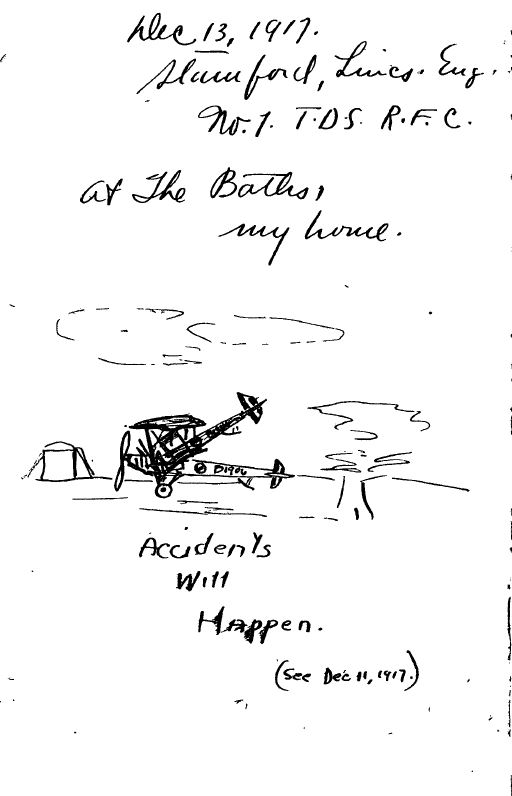

Stamford

Deetjen’s responsibilities as second in command to Springs earned him a place among those picked to go to No. 1 Training Depot Station at Stamford, despite his lack of flying experience, and he and nineteen others left for flying school there on November 5, 1917. Four days later, “I got a 15 minute joy ride in the Curtiss JN 4A No. B1914. . . I am assigned to the early squadron. Lorries leave here at 6 A.M. And believe me it’s cold getting out of bed at that hour when all is dark & wet out. It was great fun up there though, to see the sun rise and the moon & stars disappear and then to slowly see the mists clear that hung in each little vale & valley.”23 Living accommodations at Stamford were initially particularly abysmal, but, after Deetjen complained, he and others, including Roth and Raymond Watts, were moved to the Work House, which was better, if a longer hike to the air field. Between the weather and the limited number of planes, there was much cause for discontent, occasionally offset by trips to Burghley House (“the castle of the Marquis of Essex,” situated just outside Stamford; “‘Mrs.’ Lady Essex was there”) and to London.”23a At Thanksgiving, Deetjen and others went up to Grantham for a reunion, football, and turkey.

By December 19, 1917, Deetjen still had only just under four hours flying time, but when his instructor, Pearson, asked him whether “I felt I could go solo. . . . I replied in the affirmative.” His first solo trip went well, but on landing, “I was going to shoot off again when I saw Pearson waving his arms to halt.” Pearson climbed in the plane and said “‘Ainsworth is killed’. . . . I didn’t believe it for he was a good flier. Pearson taxied her back & when we got out the news was confirmed. He was stunting when at 3000 ft. his left wing snapped off, & he came down like lead.”25 Harold Ainsworth, of the first Oxford detachment, was the first of many men from the Oxford detachments to be killed in training.

On Christmas Eve, Deetjen began four days leave, which he spent in Scotland, travelling with first Oxford detachment member Edward Milton Wilcox, and meeting, coincidentally, Payson, Harvard DeHart Castle, and Robert Jenkins Griffith (or Edward Addison Griffiths?) in Edinburgh. Back at Stamford, weather and lack of planes continued to interfere with flight training, but on January 5, 1918, Deetjen was able to solo in a DH.6.

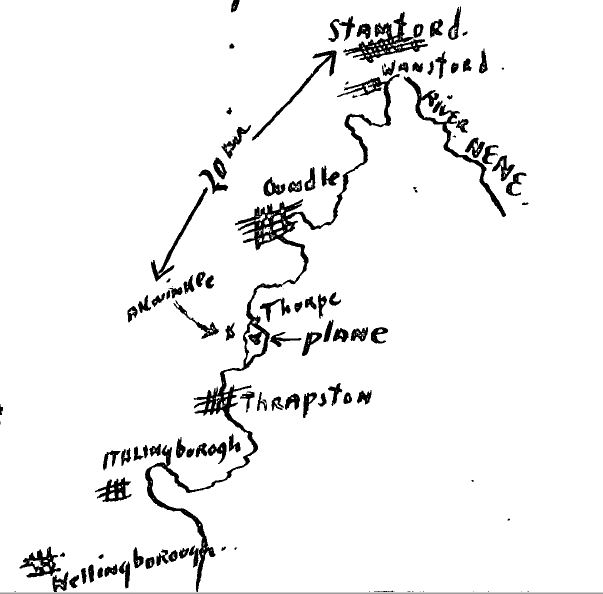

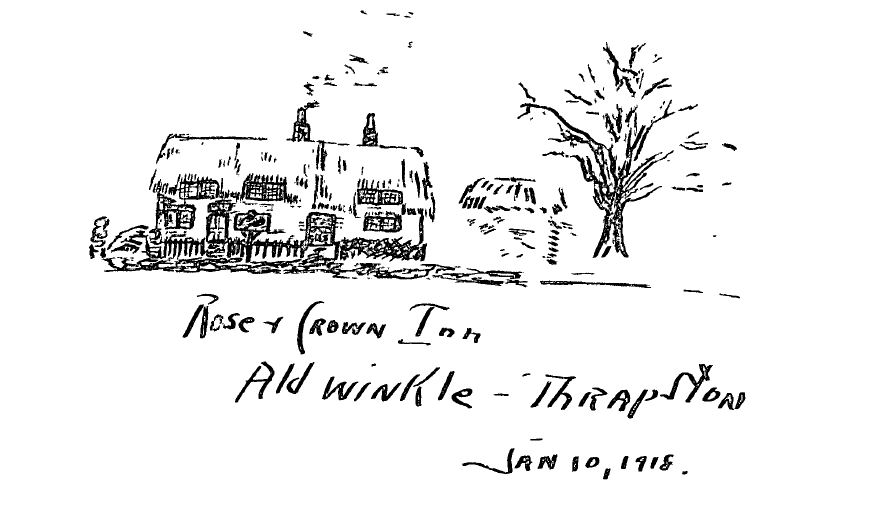

Two days later, he was flying a DH.6 in bad weather when his engine failed, and he made a forced landing near Aldwincle, about fifteen miles south of Stamford. With the help of local men (and “a devil of a pretty W.A.A.C.”), he got the plane securely pegged. Before the job was done, it was twice blown away by the wind, “tearing her tail skid completely off . . . and the lower left aileron was crushed. All this after landing beautifully, is what takes the starch out of a fellow.”26 Deetjen stayed at the home of the local school master until he was able to return by ground to Stamford on January 10, 1918.

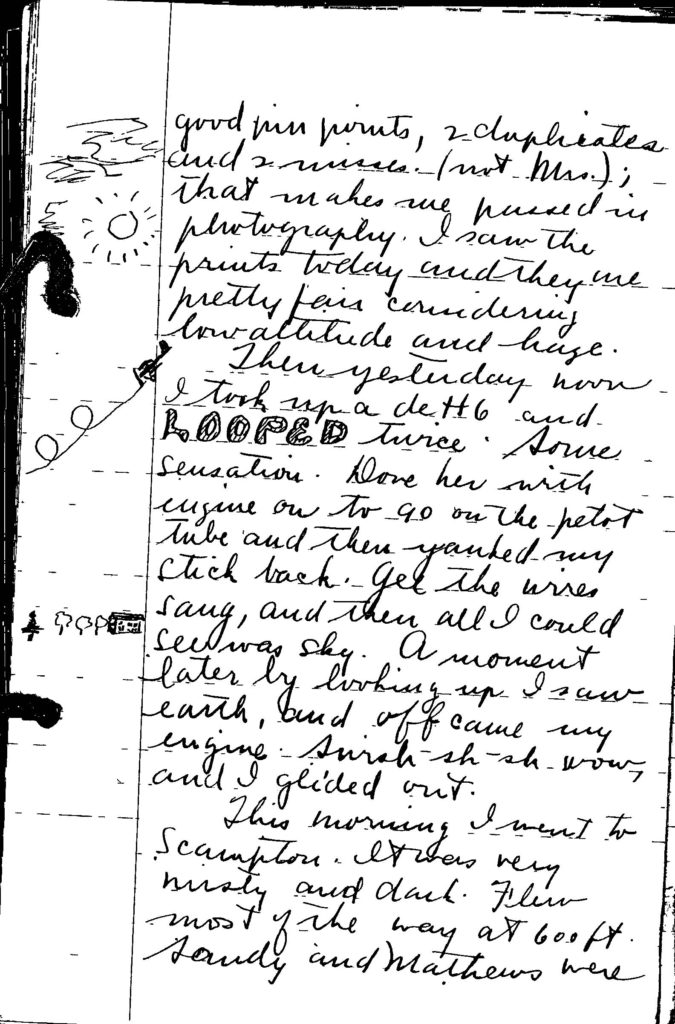

Four days later he wrote that “I have completed my time here on a deH6. . . . I am recommended for a deH4. At 20,000 ft., it is the fastest buss of the Allies. Only the German Albatros can beat it. But the work is for Long Bombing, Reconnaissance, and Photography. That just suits my taste.”27

Waddington

On January 16, 1918, Deetjen, along with Julian Carr Stanley, Carlton, and Walter Chalaire, left Stamford for Waddington, where “one of the Italian Detachment, named Sharpe was killed.”28 Deetjen was assigned to No. 51 Training Squadron: “I am to stunt a deH6 with [instructor Barnard] and then go to BE2E’s.”29 After some dual stunting, Deetjen went up on his own on January 21, 1918: “I tackled vertical banks, stalls, side slips, and nose dives. On the vertical bank I was more or less scared most of the time and I can’t get it. I’ll stick to it though and work up a little nerve and then try it till I can do a perfect one. On the stall and nose dive, I always think of Joe Sharpe’s death. He got beyond the vertical.”30 Weather and the unaccommodating Barnard made Deetjen feel frustrated with his progress, but he persisted. The squadron C.O. Major Lawrence Arthur Pattinson—whom Deetjen was later to encounter in France as C.O. of No. 99 Squadron—sometimes pushed, sometimes replaced Barnard, and on February 12, 1918, took Deetjen up in a DH.6 “and had me do spirals once again. On one turn when I was just past 45 degrees with too much nose he warned me to pull back me [sic] stick. Not thinking, I did so at once, when low and behold I can’t tell what did happen. I cut engine and dove at once. I figured I was in line for a beautiful blow up by his nibs. Instead the old boy’s shoulders were shaking in convulsions. All he hollered was, ‘Land.’ And the whole bloomin’ way down he laughed. When we pulled up he said ‘My boy, that was the most perfect Immelman turn yet made in a deH6.’ So now whenever I pass him he just chuckles away as though it were the funniest thing in the world.”31

Major Pattinson forwarded Deetjen’s name for a commission on February 20, 1918.32 Deetjen passed various tests (height, cross country, bombing, etc.), participated in a mock aerial battle against Ervin David “Molly” Shaw, and finally, on March 5, 1918, went solo on the squadron’s service plane, an R.E.8., thus fulfilling the last requirement for graduation from this stage of R.F.C. training.32a

Graduation entitled him to four days leave, which he spent in London with Leo McCarthy, with whom he roomed at Waddington. When Deetjen returned on March 12, 1918, he learned he had been transferred to No. 44 T.S., also at Waddington. That afternoon, the recently commissioned George Orrin Middleditch offered to take him up on a joy ride in a DH.4, but Deetjen went up instead with his new instructor, [Arthur Harold] Beach.32b “Chick [Chester Arthur] Pudrith took my place with George. A 4 is a wonderful big buss and I had 15 minutes of real joy ride. When I got home word came that George had killed himself in a climbing turn at Scampton and Chick was hurt on the head and leg.” In fact, Middleditch came out of the wreckage alive but badly injured; he died soon thereafter. Deetjen made frequent visits to Pudrith in the hospital. The outlook seemed to be improving, but about seven weeks after the crash, on May 3, 1918, Deetjen wrote in his diary that “Pudrith passed away day before yesterday at 3 A.M.”33 Deetjen was keeping track of fatalities among his fellow second Oxford detachment members and went on to note that “Chick makes the 15th man gone out of 150. So to date it cost 10%.” The casualties were numerous, but not yet quite as numerous as Deetjen’s calculation on this day. As of May 3, 1918, eleven out of the 150 men of the second Oxford detachment had been killed in training accidents (George Atherton Brader, Harold Kidder Bulkley, Carlton, Roy Olin Garver, Lloyd Ludwig, Middleditch, Clark Brockway Nichol, Pudrith, Sharpe, Elwood D. Stanbery, and Stillman), and one (Joseph Ralph Sandford) had been killed in action. Deetjen was probably not distinguishing between first and second Oxford detachment members and thus including men from the first Oxford detachment (Ainsworth, Lindley Haines DeGarmo, and Thomas Cushman Nathan) in his list of fifteen; he had also been misinformed that William Hamlin Neely of the second Oxford detachment had died.33a

On March 14, 1918, Deetjen received his R.F.C. graduation certificate; he flew DH.4s dual and then, a few days later, solo. By March 26, 1918, he was being pushed to move on to Marske, but “I’m insisting on my full 5 hours on deH4s and completion of all tests.” Three days later he was elated to receive his commission (along with Shaw and Fred Trufant Shoemaker), but also deeply shaken by a serious crash: “I spun into the ground from between 50 and 70 feet.” He was doing his first solo on a DH.9 and gaining confidence when, as he was completing a turn, “her lower wing suddenly switched to the vertical and her nosed dropped like lead and I felt her spin.” Some of the impact of the crash was absorbed by the soft earth of a muddy field, and his only injury was a broken nose. Inspecting the plane afterwards, Deetjen found that the sand bag used to weight the observer’s seat had come loose and apparently “dropped on the joy-stick socket, knocking it sideways and forwards.”34

Marske-by-the-Sea

By the end of the day on April 4, 1918, Deetjen had flown 44 hours and twenty minutes solo, passed all his tests and exams at 44 T.S., been placed on active duty (and thus, by American regulations, was finally permitted to wear his wings and dress like an officer), and had been ordered, along with Shaw, to depart for the No. 4 Auxiliary School of Aerial Gunnery at Marske-by-the-Sea the next morning.

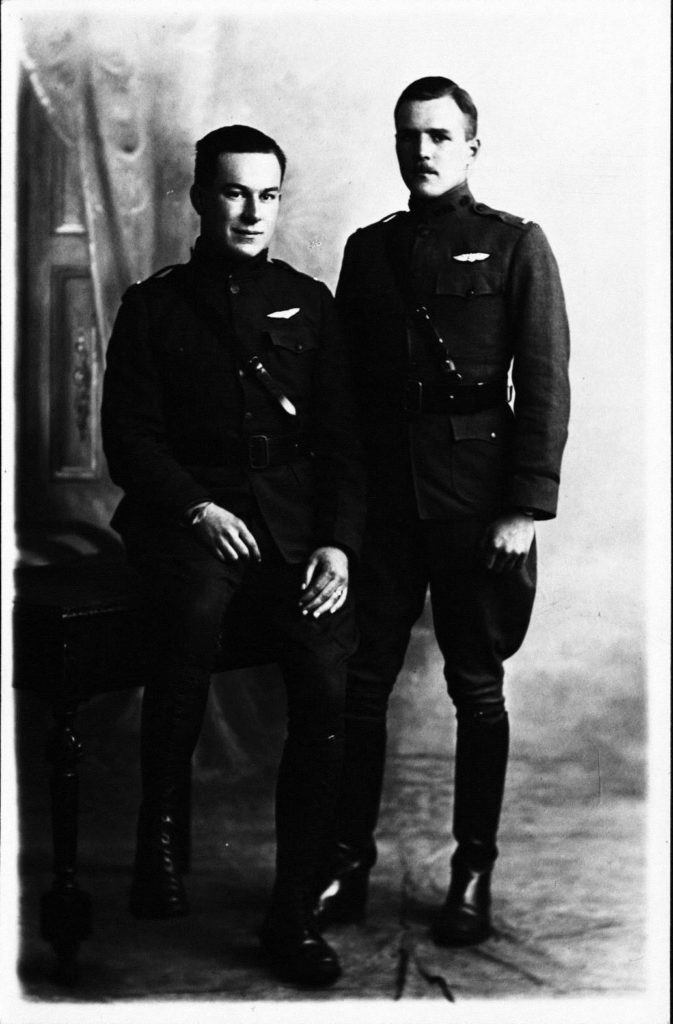

On April 8, 1918, Deetjen wrote of Marske: “Here we are about 400 yards from the sea, and the bracing air and sunshine make us sleep and eat more than ever. . . . The course consists of a week of ground work, on C.C. Gear and Vickers guns. First theory, then stoppage and deflection practice on the range. . . . Then later we do aerial firing on Bristol fighters.” In between gunnery practice and exams, Deetjen played baseball and made trips to Middlesbrough with Shaw to see shows and to get their picture taken. Unexpectedly on the evening of the 15th Deetjen was ordered to London. The next day he was hauled up before Lt. Geoffrey Dwyer and Major William A. Larned at the Aviation Office to be told he had violated censorship rules by having “written home about DeH4 and DeH9 and said that my overseas work would be long distance bombing and reconnaissance.”35 Arthur Richmond Taber, of the second Oxford detachment, and Harold Worth Vassar of the first had been sent summarily to France for a similar infraction. But Deetjen got off with a slap on the wrist and enjoyed the remainder of his stay in London, where he ran into Chalaire, Field Eugene Kindley, Joseph Kirkbride Milnor, and James Whitworth Stokes of the second Oxford detachment, as well as Frank (“Red”) Whiting and George S. Patterson of the first. About a week after his return to Marske, Deetjen had completed all his aerial tests. The same day he read in an Aviation Office circular that his friend Sandford (“Sandy”), who had recently gone to France, had been reported missing.36

Stonehenge

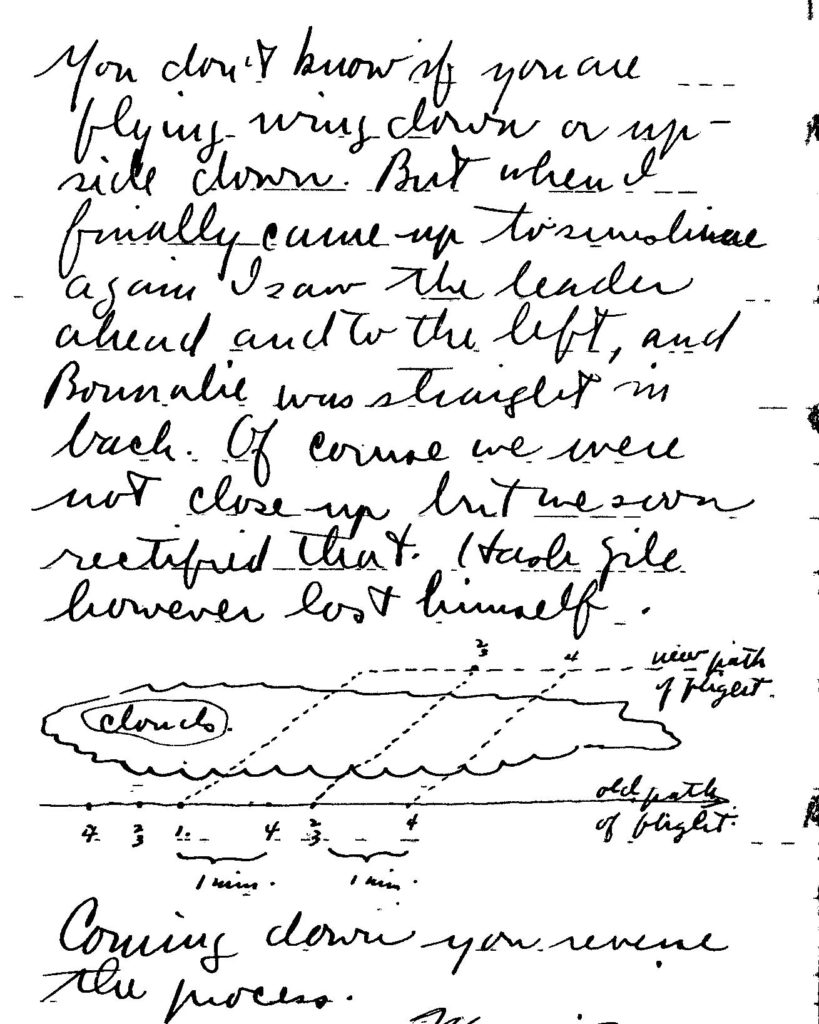

A few days later Deetjen left Marske and Molly Shaw, bound for the No. 1 School of Navigation and Bomb Dropping at Stonehenge. He arrived in London on April 23, 1918, where he met up with Allan Francis Bonnalie of the first Oxford detachment, and took the train to Amesbury. The men training at Stonehenge, now including John Warren Leach, Harry Adam Schlotzhauer and Stanley of the second Oxford detachment, and Harold Hatch Gile of the first, were apparently quartered at Larkhill. “The drome is a mile off and we must walk it. . . . On the way out this morning we passed a German prison camp, and some old Roman ruins. Or rather Druid Temple ruins.”37 “We had our first lecture on navigation. I never dreamed of the possibility of aerial navigation. No more guess work to laying a course than there is to adding 2 + 2. But it is harder. We can’t follow roads, or railways anymore. Must allow for wind, speed, deviation, variation, and then time ourselves to destination. Then we fly by watch and compass only.”38

At Stonehenge Deetjen initially flew B.E.2e’s, now with an assigned observer; they practiced navigation, photography, cloud formation flying, and bomb dropping. He had an opportunity to fly in a Handley Page and was suitably impressed by its size. That same day “while walking home we watched a deH9 flying. Suddenly with a deafening sound the wings folded up and left the buss. The fuselage, with engine full on, made a spin or two and then came down to earth hell bent for election. ’Twas an awful roar that you could hear for miles. I’ll bet it reached 260 M.P.H. Later it developed that Bob Griffith of our detachment was pilot. He had an American A.M. with him. . . . That makes at least 16 of our original 150 gone west.”39

By mid-May Deetjen was piloting a DH.9 and pushing up to an altitude of 12,000 feet. By May 20, 1918, he had done eighty-five hours solo. The next day he and some friends set off for a brief holiday at Weston-Super-Mare; on returning, he, Gile, and Bonnalie were “called to report at once for overseas. To France at last. But sad to say my name was dropped. . . .”40 A few days later, however, he heard that it would be his turn on May 28, 1918. His next diary entry was written May 30, 1918, at the No. 2 A.S.D. pilots pool at Rang-du-Fliers, France: “Here we are at last. And still must wait some time before I can get clubby with Fritz.”

No. 104 Squadron I.A.F.

Deetjen “left No. 2 A.S.D. on June 3, at 8 P.M. My orders are to join 104 Squadron which was at Winchester only three weeks ago, so they are mostly green hands like myself, and may not yet have crossed the lines. They are a deH9 Squadron. Of course Molly [Shaw], Red [Whiting], and the rest kidded the life out ’o me, claiming I was ‘cold meat’ since you usually are in a green outfit.”41 Four days later, after complications of lost luggage, Deetjen arrived at No. 104 Squadron R.A.F. in Azelot, a few miles south of Nancy. “This is a very pretty portion of France. The days are warm but nights cold. You might call this section the rolling foothills of the Vosges. Red poppies on all the fields. The Moselle River is about 2 miles west of us. . . .”42

No. 104, which had arrived at Azelot on May 20, 1918, was one of the four long-range day bomber squadrons of the Independent Air Force (the others were 99, 55, and, eventually, 110). The I.A.F. came into existence on June 6, 1918, (the day before Deetjen’s arrival at 104) and, operating independently of the other forces, was to undertake bombing of aerodromes, railroad transport, and industrial centers inside Germany.42a

Charles Louis Heater later described Deetjen as “the first American on active service with the Independent Air Force.”43 He was the first Oxford detachment man with the I.A.F., but Deetjen’s hut mates (in addition to Andrew Moore from Canada, Reginald James Searle from South Africa, and Wilfrid John Rivett-Carnac from England) included James Moffat Valentine, Frank Henry Beaufort, and Oscar Jacob Lange, all Americans. Valentine had been with 104 since January; Beaufort and Lange had been assigned to 104 in mid-April and mid-May, respectively.44

Deetjen had three weeks to acquaint himself with the squadron and the area before he could participate in a mission; this, according to some, was standard R.A.F. practice.45 June 8, 1918, was to be 104’s “first stunt. They are going to bomb Metz. And they won’t take me. I pleaded with Major Quinnell but he says no.”46 He had to be content with practice flights. On June 9, 1918, Deetjen went up with Walter Edward Flexman as his observer. “They have given me a mighty poor buss, which happens always to the last man to join a squadron. It took me an hour to reach 7000. . . “ Deetjen and Flexman put their toes over the lines near Moncel, tested guns, and Deetjen had his first experience of anti-aircraft fire. “This is the 1st Archie. I was often gassed in England by C.O.s, and now I must meet my first foe.”47 Deetjen records no flights in his diary over the next few days, but Flexman went up again on the 13th, this time serving as observer to Rivett-Carnac on a raid; the raid was successful insofar as bombs were dropped on a factory and railway at Hagondange, but enemy aircraft attacked them, and Flexman was hit in the lung by machine gun fire and died; Rivett-Carnac was shot in the foot. Deetjen later visited his former hut mate in hospital at Charmes.48

On June 15, 1918, Deetjen flew for an hour until his engine “busted at 7000 feet”; it was repaired, and Deetjen took his plane up again two days later, only to bust it up on landing. He anticipated a sharp reprimand, but his flight leader, Captain Jeffrey Batters Home-Hay, simply remarked “Tough luck, Deetjen.” On June 19, 1918, he had the pleasure of flying the squadron’s new machine, C5720: “she flies just like a scout.”49

On a couple of evenings Deetjen went into Nancy with squadron mates; on one occasion they had dinner with men from the U.S. 27th Aero (“Fred Norton of O.S.U. was ringleader”) which was stationed nearby at the Toul aerodrome.50 There were also guest nights at 104; on one occasion, “Major Quinnell spilled old Major Pattinson . . . flat on the floor.” “Liquor will get some of these ducks way before the Hun does.”51

The evening of the 23rd Deetjen was orderly officer. “. . . at 7:30 P.M. the clouds lifted and for the 1st time in ten days our outfit went over. This time they bombed Metz.” Deetjen put out flares for them as they came home in the dark. When the weather cleared early the next morning, 104 went out again, this time to bomb the railroad at Saarbrücken. “Coming home they had a fight and Jack Lange’s buss was riddled with bullets . . . Jack had a bullet in the leg, but it was merely a scratch.” That afternoon Deetjen had the melancholy task of going to Charmes “to forward Bruce’s kit” (William Bruce had gone missing on May 25, 1918, piloting a plane from Andover in England to France.) The next day, June 25, 1918, “the outfit went over to Karlsruhe Germany. They bombed it neatly, but [Stanley Charles Mathew] Pontin and [Frank Waring] Mundy both landed in Germany. The formation was attacked by 6 Huns.” Deetjen subsequently notes that Mundy landed in allied territory, but was wounded and his observer, Hugh Arthur Bruce Jackson, killed; another pilot, Anthony William Robertson, “has a blighty in the arm.” “That was a pretty heavy toll extracted for that Karlsruhe raid. Thursday it is my turn to go over.” He goes on to remark: “Several new German aerodromes have sprung up just over the line. Their scouts are more daring than formerly, and they are always waiting for us.”52

On the 26th, the squadrons of the I.A.F. targeted Karlsruhe; “Jimmy Valentine got lost, went down the Rhine turned due west and when he had crossed the lines he landed. He was only 6 miles north of Switzerland.”53 Deetjen took Valentine’s turn as orderly officer.

Finally, on June 28, 1918, Deetjen took part in his first raid, with Frank Pargeter Cobden as his observer. “My first raid was a failure…. I [was] flying right rear man. We climbed to 10,000 feet, and the leader was just shooting over a cloud when I ran plumb into it bearing due north. I held this course for about 10 minutes when in a break overhead I saw the formation was just over me. But the clouds swallowed us again, and after 12 minutes I lost track of everything, and so I turned south diving thru the clouds as I came. St. Nicholas was the first thing I saw. I landed just twenty minutes before the formation returned.”54 (Deetjen’s observer, Cobden, was killed in a raid on Kaiserslautern July 7, 1918; Cobden’s pilot on that raid, Andrew Moore, became a prisoner of war.55)

The last paragraph of Deetjen’s last diary entry (June 28, 1918) reads: “Because of casualties and on account of Capt. [Joseph Milne] Heap and another being sent home (not fit) our squadron has been reduced to two active flights, namely ‘B’ and ‘C.’ ‘A’ is a training flight and now has seven new pilots all waiting their three weeks.”

No. 104 Squadron apparently did not fly the next day, but on June 30, 1918, two formations from 104 set off at 4:55 a.m. to bomb barracks and the railway station at Landau about eighty miles to the northwest of Azelot. Deetjen, flying DH.9 C5720 with South African Montague Henry Cole as his observer, was in Home-Hay’s formation. The formations were attacked on the way out, but reached Landau and dropped their bombs. Turning back towards France, they once again encountered enemy aircraft, possibly as many as twenty, including ten Fokkers from Jasta 70.56 C5720 was seen “going down in control but with flames” east of the lines.57 German pilots Heinrich Krueger and Dörr, both of Jasta 70, each claimed to have shot down a plane similar to the type Deetjen was flying in the area, and Krueger, according to at least one source, was credited with bringing down C5720 near Schirmeck.58

It was initially hoped that Deetjen and Cole were missing in action and perhaps prisoners of war. But by late August, the Red Cross reported that Deetjen’s remains had been interred at Rothau in Lorraine (about a mile and a half south of Schirmeck), and the list of A.E.F. men killed and wounded published on September 24, 1918, includes Deetjen among those killed in action.59 Deetjen was reinterred at the Meuse-Argonne American Cemetery.60 Cole, initially interred at La Broque, near Schirmeck, was reburied at the Plaine French National Cemetery, France.61

Epilogue

In the spring of 1920 Deetjen’s parents and sister went to France to locate his grave.62 Deetjen’s father was also seeking treatment in Holland and Switzerland for a heart condition; he died October 6, 1920, on the return voyage.63 Deetjen’s mother returned to Europe to visit her son’s grave in 1922 and 1931.64 Deetjen’s name appears on the monument to World War I soldiers and sailors in Edgemont Park in Montclair, New Jersey, that was designed by Charles Keck and dedicated in 1925.65

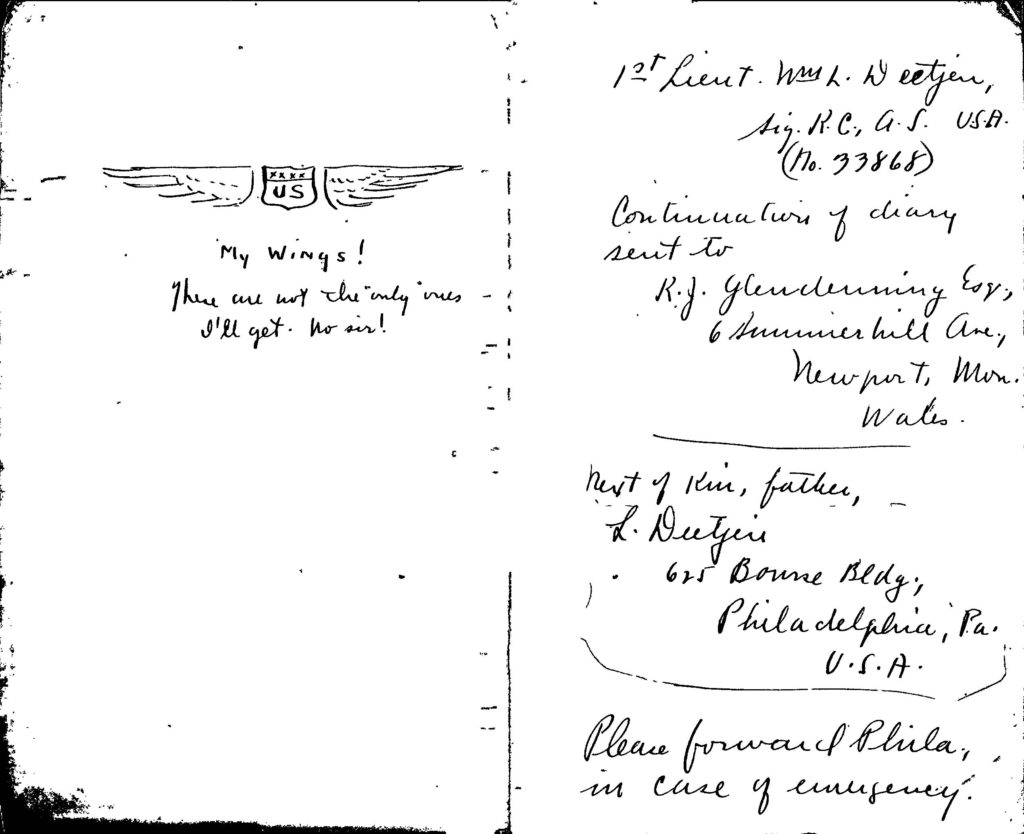

Deetjen had kept his diary in three notebooks. On April 10, 1918, he wrote: “Today I mailed Mr. R. J. Glendenning, at 6 Summerhill Avenue, Newport, Mon., the 1st two books of this diary. The second one is in the looseleaf note book—green cover—and mixed with some Aerial Gunnery notes.” Robert James Samuel Glendenning of Newport in Monmouthshire, Wales, had a brother, William John August Glendenning, who had for a time resided in Manheim, Pennsylvania.66 Presumably the Glendennings counted as trusted family friends, and Deetjen felt it safer to post the diary initially to a European address, rather than mailing it overseas. At the end of the third notebook Deetjen wrote “In event of a trip ‘West’ please wrap in another packing and send to my father.” The diary was handed down to his niece, June Goes Seaman, who, around 2005, presented it, along with Deetjen’s photo album, to the Wisconsin Historical Society.

mrsmcq June 13, 2017

Notes

(For complete bibliographic entries, please consult the list of works and web pages cited.)

1 Deetjen’s date and place of birth are taken from entries in his father’s passport application, where his first name is given as “Wilhelm” (his middle name sometimes appears as Louis). See Ancestry.com, U.S. Passport Applications, 1795-1925, record for Ludwig Deetjen. The photo is taken from “Lieutenant William L. Deetjen Killed in Action.”

2 Ancestry.com, 1900 United States Federal Census, records for Johan L, Louisa M, and William L Deetjen.

3 Sieber, “Philadelphia [Newsletter].”

4 See Ancestry.com, New York, Passenger Lists, 1820-1957, records for Ludwig and Marie Deetjen; Ancestry.com, U.S. Passport Applications, 1795-1925, record for Louise Deetjen.

5 The National Archives (United Kingdom), Royal Air Force officers’ service records 1918-1919, record for William Ludwig Deetjen.

6 He is listed as class of 1913 in an “S. M. A. Honor List” after the title page of The Blue and Gold: The Yearbook of the Staunton Military Academy for 1919 (unpaginated). He is listed as a sophomore at the Wharton School on p. 107 of The Record of the Class of 1915.

7 Trafton, “New York [Newsletter],” p. 318; entry for William L. Deetjen in R. L. Polk & Co, R. L. Polk and Co,’s 1917 Trow’s New York City Directory Boroughs of Manhattan and Bronx.

8 Deetjen, Diary, August 8, 1917. I am grateful to Mike O’Neal for pointing out Deetjen’s connection to Montclair and the Montclair Battalion.

9 Information in this paragraph is taken from Deetjen’s diary entries for August 8, 1917–September 20, 1917.

10 See “Aviation Novices Qualify.”

11 “Ground School Graduations [for August 25, 1917].” Deetjen mentions his July 28, 1917, graduation in the opening entry of his diary (August 8, 1917), and his name appears in a New York Times article datelined August 4, 1917, that includes a list of recent Cornell and M.I.T. ground school graduates (“Aviation Novices Qualify”); Deetjen kept a copy of this article in his diary.

12 Deetjen, Diary, September 21, 1917. Lt. Salmon was presumably Hamilton Henry Salmon, Jr.

13 Deetjen, Diary, September 20, 1917. This was perhaps an informal designation; on the passenger list for the Carmania, Griffiths, Horn, Mooney, Springs, and Stokes are accorded the rank of sergeant; Deetjen appears as a private. See War Department, Office of the Quartermaster General, Army Transport Service, Lists of Outgoing Passengers, 1917 – 1938, Passenger list for Aviation Section, Signal Corps, on Carmania, sailing Sept. 18, 1918, from New York City.

14 Deetjen, Diary, Sept. 20–23, 1917.

15 Deetjen, Diary, October 4, 1917.

16 Springs, Letters from a War Bird, pp. 211–12.

16a Winslow, RFC/RAF No. 56 Squadron Diary of Paul Winslow. 1917-1918, entry for October 9, 1917; I take “Rietygen,” and “Riety” to be mistranscriptions of Deetjen’s name and nickname.

17 Deetjen, Diary, October 4, 1917.

18 Deetjen, diary entries for October 9 and 27, 1917.

19 Deetjen, Diary, October 21, 1917.

20 Deetjen, diary entries for October 23 and 27, 1917. On November 1, 1917, he wrote “Am going to Andersons tonight for dinner with Barksdale,” but one hopes this was a slip of the pen and not the prelude to a social gaffe. Barksdale wrote in his diary on that date: “Being especially invited Dietzjen [sic] & I took dinner with Mr. Miss & Mrs. Morrison (of N.Y.).”

21 Deetjen diary entries for October 21 and 23, 1917. The celebrations of the first Oxford detachment and the aftermath are also recounted in the October 22, 1917, entry in War Birds; in Barksdale’s diary entry for October 8 [!] and 20, 1917; Foss’s diary entries for October 20 and 22, 1917; and Springs’s letter of November 1, 1917, to his stepmother (Springs, Letters from a War Bird, pp. 43-45).

22 Deetjen, Diary, November 4, 1917.

23 Deetjen, Diary, November 9, 1917.

23a Deetjen, Diary, November 14, 1917.

24 Deetjen, Diary, December 5, 1917.

25 Deetjen, Diary, December 19, 1917.

26 Deetjen, Diary, January 9, 1918.

27 Deetjen, Diary, January 14, 1918.

28 Deetjen, Diary, January 18, 1918. Joseph Hiserodt Sharpe was killed on January 7, 1918.

29 Deetjen, Diary, January 18, 1918. Barnard was probably Franklyn Leslie Barnard, whose R.A.F. service record puts him at Waddington as an instructor, albeit at No. 44 T.S., in early 1918. See The National Archives (United Kingdom), Royal Air Force officers’ service records 1918–1919, record for Franklyn Leslie Barnard.

30 Deetjen, Diary, January 21, 1918.

31 Deetjen, Diary, February 12, 1918.

32 Deetjen, diary entries for February 23 and 28, 1918. Cablegram 678-S from Pershing making the recommendation is dated March 5, 1918.

32a Deetjen, diary entry for March 5, 1918.

32b I find no R.A.F. service record or casualty form for Beach. Deetjen refers to him only by his last name, but an A. H. Beach signed off on several pages of Vincent Paul Oatis’s Pilot’s Flying Log Book during the time Oatis was at No. 44 T.S. at Waddington. Pentland, Royal Flying Corps identifies him as Arthur Harold Beach.

33 The list of cadets and officers killed in training on p. 5 of Dwyer’s “Report on Air Service Flying Training Department in England” gives April 30, 1918, as the date of death.

33a On Neely’s putative death, see Deetjen’s diary entries for March 28 and April 2, 1918.

34 Deetjen, Diary, March 29, 1918. Cablegram 979-R to Pershing confirming Deetjen’s appointment as a first lieutenant is dated March 25, 1918; it is typical that at least a few days elapsed before news of the appointment trickled down to the man in question and became official.

35 Deetjen, Diary, April 17, 1918.

36 Deetjen, Diary, April 21, 1918.

37 Deetjen, Diary, April 24, 1918.

38 Deetjen, Diary, April 25, 1918.

39 Deetjen, Diary, May 9, 1918. Griffith’s crew was John Joseph Leighton from the American 188th Aero Squadron.

40 Deetjen, Diary, May 23, 1918.

41 Deetjen, Diary, June 5, 1918.

42 Deetjen, diary entry written June 9, 1918.

42a There is considerable controversy surrounding the I.A.F. Chapter 11 of Wise’s Canadian Airmen and the First World War provides an account and an assessment based on original documents that is worth reading. See also his description of the shortcomings of the DH.9 on pp. 293–94, 303, and 309.

43 Heater, “Americans on Day Bombing with the Independent Air Force – Royal Air Force,” p. 118.

44 See The National Archives (United Kingdom), Royal Air Force officers’ service records 1918-1919, records for James Valentine, Frank Henry Beaufort, and Oscar Jacob Lange. Beaufort’s first name in grave records is given as “Francis.”

45 Heater, “Americans on Day Bombing with the Independent Air Force – Royal Air Force,” p. 117; Read and Roland, Camel Drivers, p. 35. Over the course of writing these biographies, I have learned that a number of R.A.F. squadrons did not observe the practice.

46 Deetjen, Diary, June 7, 1918.

47 Deetjen, diary entry written June 9, 1918.

48 Rennles, Independent Force, p. 25; Deetjen, Diary, entry for June 23, 1918.

49 Deetjen, Diary, June 15, 17, and 19, 1918.

50 Deetjen, Diary, June 19, 1918.

51 Deetjen, Diary, June 23, 1918.

52 All of the quotations in this paragraph come from Deetjen’s diary entry misdated “June 26th”; it must actually have been written on June 25, 1918. Mundy is sometimes referred to as “E. W. Mundy” (in, for example, Rennles, Independent Force). There has apparently at some point been a transcription error (“F” having been read as “E”).

53 Deetjen, Diary, June 27, 1918.

54 Deetjen, Diary, June 28, 1918. Heater, “Americans on Day Bombing with the Independent Air Force – Royal Air Force,” p. 118, is thus not quite accurate when he reports that Deetjen, “was shot down on his first raid, the last of June.”

55 Rennles, Independent Force, pp. 51–52.

56 Rennles, Independent Force, p. 42.

57 Entry in Henshaw, The Sky Their Battlefield II.

58 Franks, Bailey, and Duiven, The Jasta War Chronology, indicate that Krueger and Dörr each claimed a DH.4. Rennles, Independent Force, pp. 41–42, notes that they “claimed DH4s, a common mistake even amongst experienced pilots,” and that Krueger was credited with shooting down Deetjen and Cole. Henshaw notes only that Krueger and Dörr both claimed DH’s. No first name is provided for Dörr in any of the sources.

59 “Lieutenant William L. Deetjen Killed in Action”; “Americans Killed and Wounded on the French Front.”

60 “Wm Ludwig Deetjen.”

61 “Cole, Montague Henry.”

62 Ancestry.com, U.S. Passport Applications, 1795-1925, record for Ludwig Deetjen (1920); record for Louise A Deetjen (1920).

63 Sieber, “Philadelphia [Newsletter].”

64 Ancestry.com, U.S. Passport Applications, 1795-1925, record for Marie Louise Deetjen (1922); Black, “45 Wisconsin Mothers will Visit France.”

65 I am grateful to Mike O’Neal for bringing this memorial to my attention.

66 Information based on documents available at Ancestry.com