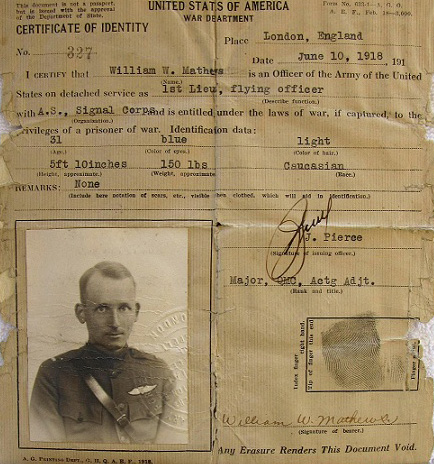

(De Pere, Wisconsin, January 4, 1887 – Los Angeles, March 21, 1974).1

Oxford & Grantham ✯ Waddington, Scampton, Catterick, Ayr ✯ No. 218 Squadron: June & July ✯ No. 218 Sqn.: August ✯ No. 218 Sqn.: October & after

Mathews was descended from families who had lived for a number of generations in the northeastern U.S.; he could trace his ancestry back to at least two Revolutionary War soldiers. His grandparents came to Wisconsin in the mid-nineteenth century and were important in the development of the town of De Pere on the Fox River west of Green Bay.2 Mathews’s parents, as well as his two sisters, both older than himself, remained active there professionally and civically until their deaths.3

In 1908 Mathews graduated from the University of Wisconsin, Madison, with a B.S. in civil engineering.4 He moved to Chicago, working for a time with that city’s sanitary district before setting up as a consulting engineer.5 His R.A.F. service record indicates that he worked briefly in 1917 for the Chicago engineering firm of Pearse and Greeley. 6 When he registered for the draft in 1917, he was employed by The Chicago, Fox Lake and Northern Electric Railway Company.7

Mathews attended ground school at the University of Illinois’s School of Military Aeronautics in Champaign–Urbana, graduating September 1, 1917.8 Along with most of the men from his ground school class of about thirty, he chose or was chosen to go to Italy for flying training and thus sailed with the 150 cadets of the “Italian” or “second Oxford detachment” to England. They departed New York on September 18, 1917, on the Carmania. The ship made a brief stopover at Halifax before joining a convoy for the Atlantic crossing. During the voyage there was leisure time, but the cadets also took Italian lessons, conducted by Fiorello La Guardia, who sailed with them, and, once they entered dangerous waters, they took turns at submarine watch.

Oxford and Grantham

When the Carmania docked at Liverpool on October 2, 1917, the aviation cadets learned that they were not to go to Italy, but to stay in England. They travelled by train to Oxford, where they spent the month of October repeating ground school at the Royal Flying Corps’s No. 2 School of Military Aeronautics.

The men were eager to start learning to fly, but, because there were not enough openings for them at training squadrons, most of them, including Mathews, were sent at the beginning of November 1918 to a machine gunnery school, Harrowby Camp, near Grantham in Lincolnshire. There they spent two weeks learning about and practicing with the Vickers machine gun.

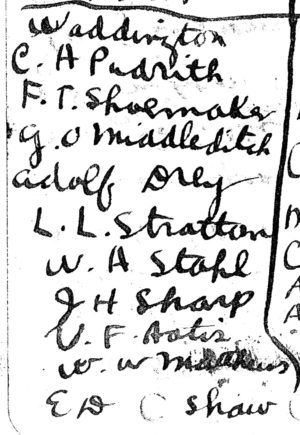

Then, in mid-November, it was determined that there was room at British flying schools for fifty of the Grantham cadets, and Mathews was among those selected. Along with nine others (Adolf M. Drey, George Orrin Middleditch, Vincent Paul Oatis, Chester Albert Pudrith, Joseph Hiserodt Sharpe, Fred Trufant Shoemaker, Walter Andrew Stahl, Lynn Lemuel Stratton, and Ervin David Shaw) he set off on November 19, 1917, for Waddington, about twenty miles north of Grantham, where several R.F.C. training squadrons were located.9

Waddington, Scampton, Catterick, Ayr

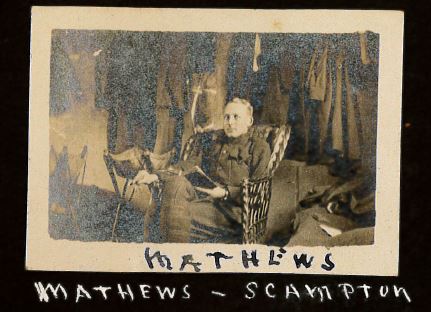

At Waddington Mathews would have begun his training on Maurice Farman Shorthorns (“Rumpties”). On December 29, 1917, he was apparently posted to Scampton, about ten miles to the north of Waddington. Murton Llewellyn Campbell, who was at No. 81 Squadron (a training unit) at Scampton, wrote in his diary that day that “About 6:30 Mathews blew in from Waddington all fed up about coming over here alone. We have a room together; was glad to see him come as it makes things livelier.” The afternoon of December 31, 1918, the two of them made a trip into Lincoln together.10

Mathews apparently made his first solo flight around the turn of the year. A brief article in the Green Bay, Wisconsin, Press-Gazette of January 3, 1918, reports that his father received a cablegram announcing that Mathews had “taken his first ‘solo’ flight, remaining in the air for over five hours.”11 It is likely that he had soloed on a Maurice Farman Shorthorn at Waddington just before coming to Scampton. Campbell’s diary entry for January 6, 1918 (“M[athews] and I have succeeded in passing off all our ground tests so will be on the Flying list in a day or so”) suggests that he and Mathews spent the first week of the New Year at Scampton doing ground work. The “five hours” of the cablegram almost certainly refers to accumulated flying time over a number of (mainly dual) flights. Once at Scampton and on the flying list, Mathews would have moved on to dual instruction on Avros. Campbell went up in an Avro for the first time on January 11, 1918, and flew solo on January 17, 1918; Mathews’s experience was probably similar. It seems likely that Mathews, like Campbell, went from flying Avros at Scampton to flying Sopwith Pups; his R.A.F. service record notes that by around the end of February he had flown “MFSH, Avro, Sop. Scout” (Sopwith Scout was the official name for what was colloquially known as a Pup).12

Campbell wrote in his diary for January 27, 1918, that he “Went over to Hackthorn Hall with Mathews for tea and enjoyed ourselves very much.” Hackthorn Hall was situated about two miles northeast of Scampton; it had been in the Cracroft family for many generations. Mathews and Campbell were guests of Edward Weston and Cicely Sophia Mary Cracroft. The Cracrofts were childless but had two nephews near the age of Mathews and Campbell serving in the military, and, like many of their generation, they evidently made it their business to welcome Americans soldiers.

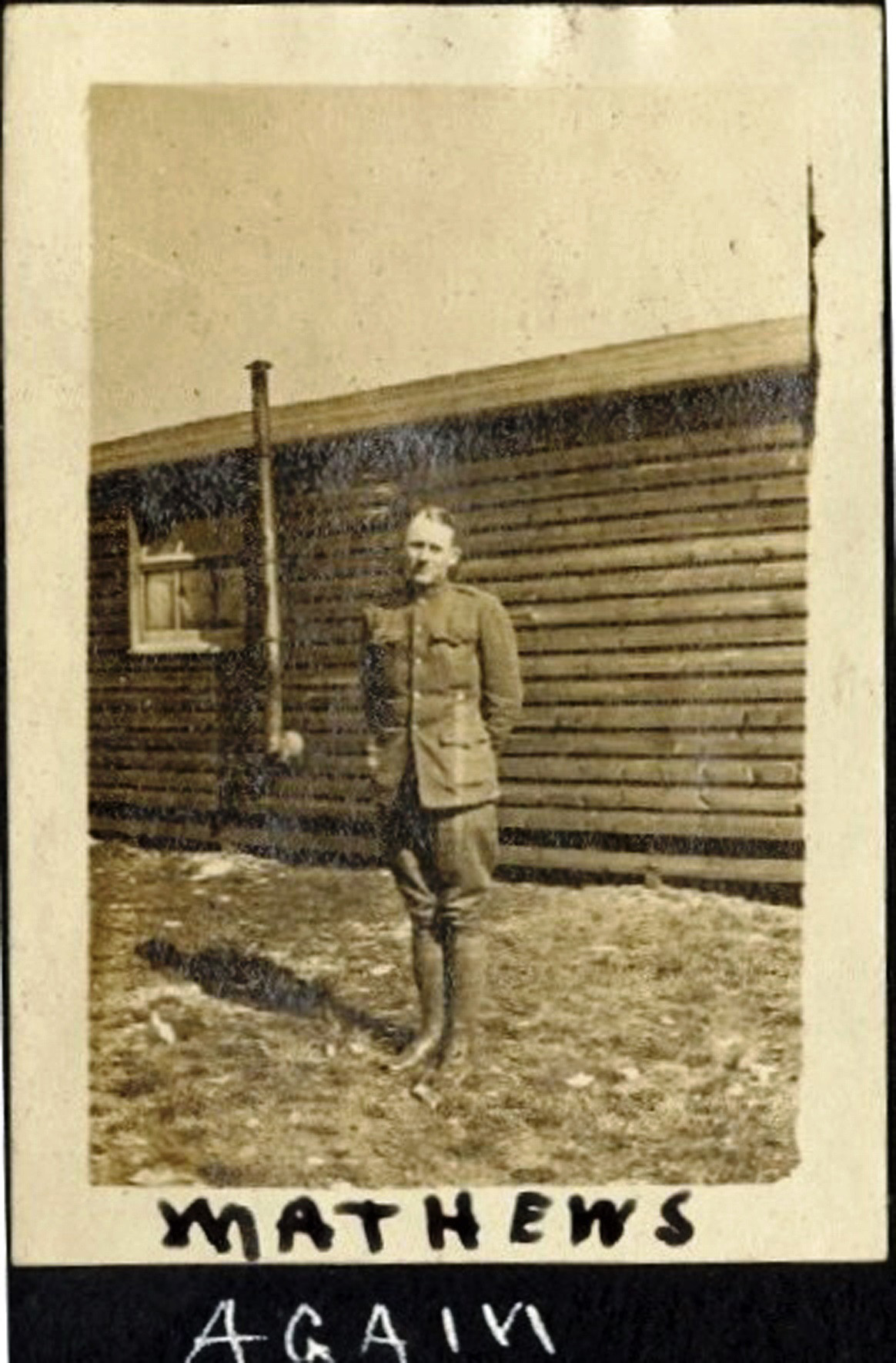

Mathews remained at Scampton through January and well into February. William Ludwig Deetjen, another second Oxford detachment member, noted flying from Waddington, where he was stationed, to Scampton on February 19, 1918, and encountering Mathews there.13 William Thomas Clements was also at Scampton off and on during the time Mathews was there and took a couple of photos of him.

Towards the end of February or very early in March 1918 Mathews was posted to No. 52 Squadron at Catterick in North Yorkshire.14 At Catterick he could have flown DH.6s (a training plane) as well as DH.4s and DH.9s. Mathews’s R.A.F. service record notes that on March 8, 1918, he “Grad C.F.S.,” i.e., completed all the requirements of this stage of R.F.C. training.15 The recommendation for his commission was duly forwarded by Pershing to Washington on March 18, 1918, and the approval came back in a cablegram dated March 26, 1918.16 Mathews was placed on active service on April 8, 1918.17 Probably towards the middle or end of May 1918 Mathews was posted to the No. 1 School of Aerial Fighting & Gunnery (which became the No. 1 Fighting School on May 29, 1918) located at Ayr and Turnberry on the west coast of Scotland, for advanced instruction on DH.9s.18

No. 218 Squadron: June & July

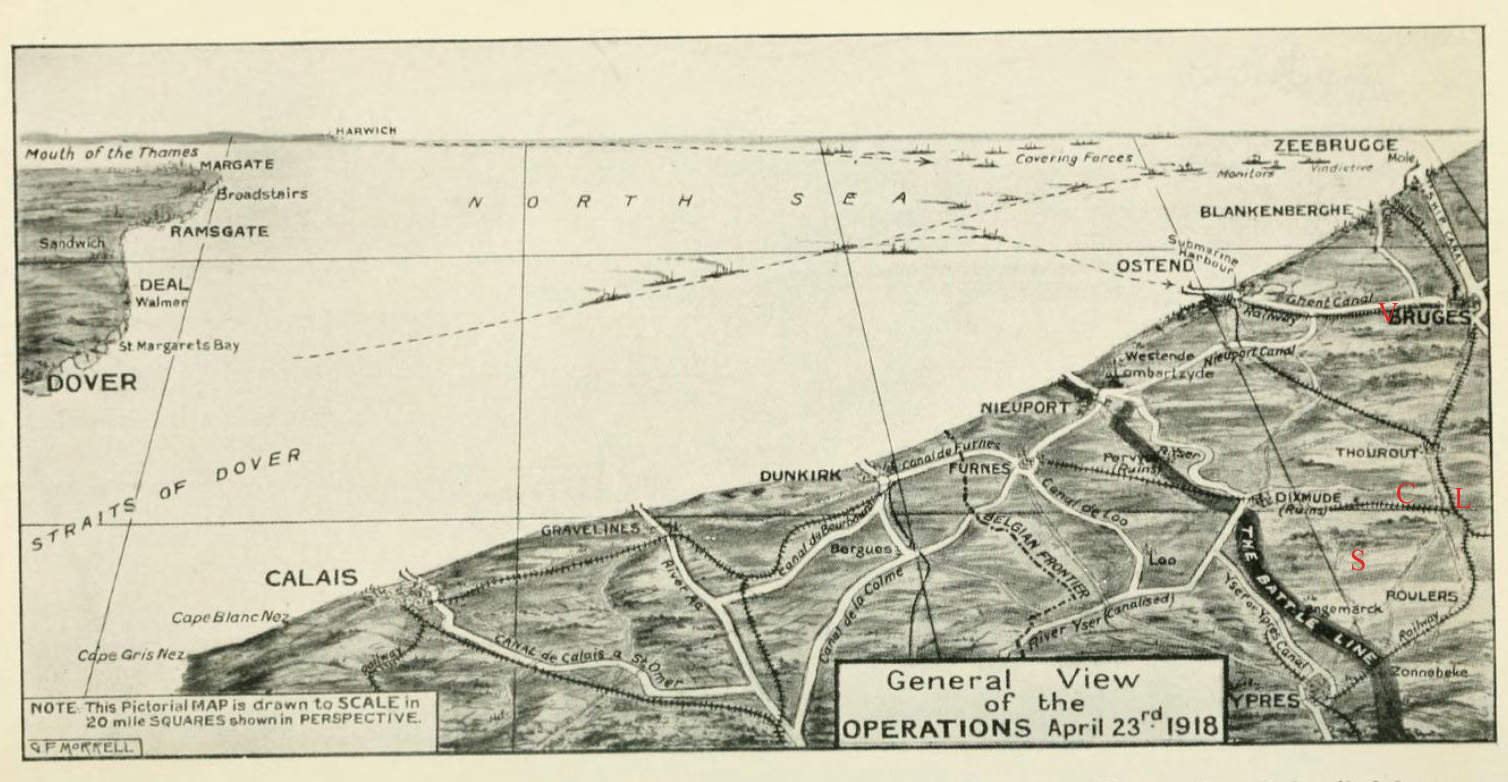

Mathews’s R.A.F. service record indicates that on June 12, 1918, he went from “1 Sch. of Fight.” to “S.E. Area . . . for 61st Wing.” A brief biography of Mathews written shortly after the Armistice indicates that he joined No. 218 Squadron R.A.F. on June 27, 1918.19 No. 218, a DH.9 squadron—also flying the odd DH.4, according to the squadron record book— was at this time part of the 61st (Naval) Wing and was stationed at Petite Synthe near Dunkirk on the Channel coast.20 Mathews was the only member of either Oxford detachment assigned to 218 and, indeed, only one of two such assigned to the 61st Wing; Walter Chalaire had joined No. 202 Squadron R.A.F., stationed at Bergues, just south of Dunkirk, on June 4, 1918. There were, however, many men from the Oxford detachments at Petite Synthe and nearby Capelle, where the U.S. 17th and 148th Aero Squadrons were stationed, and Sopwith Camels from these squadrons flew protection for R.A.F. bombers, likely including the DH.9s of 218, on their bombing missions along the Channel coast.21 And Mathews was one of many Americans who flew with No. 218 Squadron. A number of men from the U.S. Naval Reserve Flying Corps and the U.S. First Marine Aviation Force who were in line for service with the U.S. Northern Bombing Group spent time training and flying missions with No. 218 Squadron, albeit their time there was usually brief compared with Mathews’s.22

According to a short history of No. 218 Squadron written in early 1919, almost none of the pilots assigned to the squadron when it was formed at Dover at the end of April 1918 had any war flying experience; the period from May 23, 1918, when they moved to Petite Synthe, until June 10, 1918, was spent in training.23 By the time Mathews arrived, however, the squadron had flown a number of bombing raids on Ostend, which was then about ten mile inside enemy lines, and was beginning to venture beyond Ostend to target Zeebrugge and Bruges as part of the long-term effort to damage German submarine facilities.24 Squadron historian Cecil Hugh Hayward noted that 218’s DH.9s encountered “active resistance on the part of enemy anti-aircraft defences and enemy scouts” and that “so active were the aircraft defences that rarely a machine returned undamaged.”25 Indeed, Sydney F. Wise, in his Canadian Airmen and the First World War, describes two sorties at the end of June and in early July 1918 in which pilots of No. 218 encountered as many as thirty enemy aircraft.

On July 7, 1918, as part of the struggle among various entities in the British armed forces to claim and utilize inadequate aerial resources, No. 218 Squadron was combined with Nos. 38 and 214 Squadrons to form the 82nd Wing and relocated to Fréthun southwest of Calais.26 The squadron was now tasked with aiding the French and Belgian armies, but the general area targeted by their bombing missions remained essentially the same: the vicinity of Ostend and Bruges, now about twenty miles more distant from the planes’ aerodrome. If I understand the 218 squadron record book correctly, pilots would often ferry their planes from 218’s aerodrome at Fréthun to and from Saint-Pol-sur-Mer just north of Petite Synthe, setting out from St. Pol and returning there when they flew missions.

This latter document indicates that Mathews, having apparently arrived at No. 218 on Thursday, June 27, 1918, flew his first mission the following Monday, July 1, 1918: he reached his objective, Zeebrugge, and dropped four fifty-pound bombs during a flight that lasted two hours and thirty-five minutes. On July 7 and 14, 1918, he dropped four fifty-pound bombs on Bruges, and flew a second mission on July 14, this time targetting the mole at Zeebrugge, achieving “4 direct hits on mole & docks.” According to the “Flying times” document, he did not participate in a mission again until July 31, 1918, when it appears he had to return early from another attack on the mole at Zeebrugge. Why his missions were so far apart and relatively few in July is unexplained. There were some days, but not many, of bad weather; he was perhaps being given the opportunity for orientation and practice. When he did fly on the 14th and the 31st, the missions were dangerous enough: according to Trevor Henshaw’s The Sky Their Battlefield II, it was only on these days that No. 218 incurred casualties in July, both times due to anti-aircraft fire in the vicinity of Zeebrugge.

No. 218 Squadron: August, September

Mathews’s mission participation increased dramatically in August 1918; the “Flying times” document lists seventeen flights, most of them targetting Ostend, Bruges, and Zeebrugge. He had to return early from six of the missions because of engine trouble—probably only slightly over par for the course with DH.9s. And when he was returning from one of the two missions he flew on August 11, 1918, his plane, D3099, as noted above, “Hit roadway crossing Aerodrome bounced and right wheel collapsed crashing undercarriage.”

Two days after this incident, a major attack by combined U.S. and R.A.F. squadrons on the German Varsenare aerodrome took place. Bombing raids such as those that No. 218 Squadron had been making “induced the enemy to strengthen his air fighting units in Belgium. Enemy opposition noticeably increased throughout July and when, early in August, it became known that aircraft reinforcements had reached the important aerodrome at Varssenaere, west of Bruges, it was decided to make a large-scale attack on the aerodrome.”30 No. 218 Squadron was scheduled to bomb the aerodrome some two hours after the initial dawn assault on August 13, 1918, but “but owing to EA activity, target could not be reached”; 218 bombed Ostend instead.31 Mathews dropped eight twenty-five pound bombs on “Contridam,” i.e., the Konterdam area of Ostend. That afternoon, Murton Campbell, who, as a member of the U.S. 17th Aero, had participated in the raid, gave an account of his part in it in his diary that day and then noted that he “Went down to Calais for the afternoon to get away from camp and flying in general. A person feels rather relieved to get away and know that there is nothing else to be done during the day. I met Bill Mathews [sic] and we had a good afternoon together as is always the case when we get together.”

The next day, August 14, 1918, Mathews’s objective was Blankenberge, just to the west of Zeebrugge, and he again dropped eight twenty-five pound bombs, this time on railway tracks between Blankenberge and Zeebrugge. The objective for the remaining eight missions in which he participated during August was Bruges; on the four successive missions on August 21, 22, 25, and 29, he “Rtd Engine Trouble.” He reached the target and dropped his bombs on August 30, 1918, but had engine trouble the next day.

As in July, Mathews flew comparatively few missions in September: the “Flying times” document records six flights. Bruges continued to be the target; on only one of the missions, that on September 16, 1918, was it reached.

No. 218 Squadron, and Mathews, were involved in the Fifth Battle of Ypres, which commenced at the end of September. H. A. Jones provides an overview of this component of the Allied Hundred Days Offensive: “In accordance with the general Allied plan of campaign the Flanders offensive, . . . had begun at the end of September. The front of attack extended from Dixmude to St. Eloi, and the forces involved were the Belgian Army, some French divisions, and the British Second Army. . . . The general direction of the advance was to be towards Ghent, and it was hoped that . . . the Allies [could be] enabled to clear the enemy from the Belgian coast.”32 Air support was required, and the squadrons of the two wings of No. 5 Group, including No. 218 Squadron, were made available to the Belgian army; their main goal was the interruption of German rail and road communications. The offensive commenced early in the morning of September 28, 1918. The main targets of the bombers of No. 5 Group were “the railways at Thourout, Cortemarck, and Lichtervelde. . . .”33

The “Flying times” document shows that Mathews set out on three missions on the opening day of this offensive, but each time was cut short by engine trouble or the like; there are no missions listed for him on September 29 or 30, 1918. However, both the “Flying times” document and the squadron record book for October record Mathews’s participation in several missions in the first days of that month as the offensive continued.

On October 1, 1918, he and Archer, along with seventeen other pilot-observer teams, set out at 7:55 on an “air raid”; three planes (including pilot W. H. Matthews and observer Harvey Ross Murray in D3253) had to return due to engine trouble. Mathews, flying DH.9 [D]7248, reached his target near Thorout (Torhout) at 9:00 and, from 8,000 feet, dropped one large bomb (230 pounds), making a “direct hit on road” at what appears to be map reference Q 6 b (sheet 20 SE) i.e., just south of Gits, about a fifth of the way from Hooglede to Thorout; he returned at 9:25.34 Mathews and Archer are next recorded as making a “Cross Country Flight,” setting out from St. Pol in 7248 at 11:10 and arriving at 218 Squadron twenty-five minutes later. There were apparently three more raids carried out by No. 218 Squadron that day; Mathews’s name does not appear among those listed for the second and fourth raid; I find no record for the third raid.

No. 218 Squadron: October and after

By the end of October 1, 1918, “the Belgians had reached the general line [south to north] Moorslede-Staden-Dixmude.” At the same time, “messages were received from forward Belgian and French divisions to the effect that their food reserves had been exhausted, and that the bringing forward of supplies would certainly be delayed owing to the damaged state of the roads.”35 Thus the next day’s missions, according to 218 Squadron’s record book, had as their object “food dropping on Stadenburg [sic],” i.e., on the small village of Stadenberg just southwest of Staden.

That morning, October 2, 1918, Mathews and Archer ferried D7248 back to St. Pol-sur-Mer. They were one of twenty-five pilot/observer teams that set out from St. Pol in the morning with food parcels, but were also one of two teams who had to turn back after only ten minutes; no reason is supplied, but there was presumably engine or similar trouble. In the afternoon Mathews and Archer ferried [D]2922 back to home base; another team, pilot Harold Clitherow Margrett and observer (James Mills?) Wilkie flew D7248 back to Fréthun.

Despite bad weather on October 3, 1918, sixteen DH.9s and one DH.4 from No. 218 Squadron set out at 10:35 on a bomb raid. Mathews and Archer were flying DH.9 C1328; at 11:30 they dropped five fifty-pound bombs over the Westende batteries (Matthews with Murray did the same ten minutes later; D7248 was being flown on this mission by Margrett and observer Hitchin; engine trouble forced them to return early). Mathews and Archer “landed on the beach” at 12:10 after a flight of one hour and thirty-five minutes; later that afternoon they ferried their plane from the beach back to 218 Squadron and did not participate in the second raid undertaken by No. 218 mid-afternoon.

No. 218 Squadron flew two missions on October 4, 1918. Thirteen DH.9s and one DH.4 took off at 7:00 in the morning; Mathews and Archer were again in D7248. At 8:00 they dropped a 230-pound bomb from 12,000 feet “On road crossing tracks S. of Thourout” (map reference F 19 c, sheet 20); on their return they contributed to the squadron’s detailed observation report regarding, i.a., railway traffic around Thourout. Shortly after 1:00 that afternoon Mathews and Archer flew D7248 from St. Pol to 218 Squadron. At 5:00 fifteen planes from No 218 Squadron set off on a second bomb raid with Lichtervelde as the main target. Four of the planes, including Mathews’s D7248, experienced engine trouble and were unable to reach that target. Nevertheless, Mathews and Archer were able to drop a 230-pound bomb from a height of 9,000 feet “Alongside Nieuport-Ostende Canal about 3 miles E. of Nieuport” before returning. H. A. Jones concludes his account of the Flanders Offensive by remarking that “Throughout the 4th, and during the succeeding night, the bombing of enemy communications and columns continued, a notable result on the 4th being great destruction at Lichtervelde railway sidings.”36

The only entry for Mathews in the extant 218 Squadron records for October 5, 1918, shows him and Archer ferrying D7248 from St. Pol to 218 Squadron in the morning. There are no further entries in the extant pages of the No. 218 Squadron record book that clearly record Mathews’s activities. It is possible that he (rather than Henry William Matthews) was the pilot who flew with observer George Millatt Worthington on a bomb raid in DH.9 D605 on October 18, 1918 (the same day that D7248 experienced engine failure yet again and sank after a forced landing in the sea) and again with Worthington in B7677 the next day. There is, however, a casualty return for either October 6 or October 7, 1918, that documents Mathews’s participation, along with his observer Archer, in a bomb raid on Hooglede, flying D3904: “Owing to engine trouble, machine was forced to land on the Beach. Machine returned to Depot for repairs.”37 Typically dismal north European autumn weather had, in any case, set in, and the record book indicates that on many subsequent days there was no flying.

One of the two R.A.F. service record for Mathews (for “W. W. Matthews”) records his departing No. 218 Squadron on October 20, 1918, to join the U.S. No. 3 Aircraft Instruction Center at Issoudun; the brief post-war military biography of Mathews has him with No. 218 Squadron until October 25, 1918.38 The same biography indicates that he was assigned to the staff of U.S. No. 7 Aviation Instruction Center at Clermont-Ferrand on November 2, 1918.

Mathews returned to the U.S. in March 1919 and resumed his engineering career, initially in Chicago, and then in Gary, Indiana.39

mrsmcq September 27, 2019; reloaded to (try to) fix paragraph breaks & insert headings December 8, 2023

Notes

(For complete bibliographic entries, please consult the list of works and web pages cited.)

1 For Mathews’s place and date of birth, see Ancestry.com, U.S., World War I Draft Registration Cards, 1917–1918, record for William Wyman Mathews. For his place and date of death, see “William Mathews.” The

photo was posted by Mathews’s grandson at “W.W. Mathews.”

2 On Mathews’s descent, see documents available at Ancestry.com; on the family’s connection to De Pere, see Commemorative Biographical Record of the Counties of Brown, Kewaunee and Door, Wisconsin, pp. 68–69.

3 See “Pioneer Resident Dies at Age of 93,” “Ex-Merchant Dies Sunday,” “Music Teacher in De Pere 70 Years Dies,” and “Miss Mathews, Noted De Pere Librarian Dies.”

4 The University of Wisconsin, Alumni Directory 1849–1911, p 203.

5 Ibid., Ancestry.com, 1910 United States Federal Census, record for William W Mathews; Mathews’s advertisement on p. 5 of the Appleton, Wisconsin, Post-Crescent for April 14, 1914.

6 National Archives (United Kingdom), Royal Air Force officers’ service records 1918–1919, record for William Wyman Mathews. Note: there is a second such record evidently created for Mathews; see ibid., the record for W W Matthews [sic].

7 See his draft registration, cited above.

8 “Ground School Graduations [for September 1, 1917].”

9 Foss, Diary, entry for November 15, 1917.

10 Murton Llewellyn Campbell, diary.

11 “Mathews Flying in England.”

12 See the R.A.F. service record for William Wyman Mathews, cited above.

13 Deetjen, diary.

14 See Mathews’s R.A.F. service record, cited above.

15 Ibid.

16 Cablegrams 745-S (“William W Matthews”) and 985-R (“William Matthews”).

17 McAndrew, “Special Orders No. 205″ (“Matthews, W. M.”).

18 See Mathews’s R.A.F. service record, cited above. The March 12, 1918, entry in War Birds mentions a “Mathews” at Ayr, but the reference is probably to Alexander Ferdinand Mathews.

19 “Interesting Histories of Officers of Staff of Seventh A.I.C. and Instruction Department.” Sloan, Wings of Honor, p. 227, indicates that Mathews served with No. 18 Squadron R.A.F.; No. 218 R.A.F. would have been No. 18 R.N.A.S. (not R.F.C.) had it been formed prior to the amalgamation of the R.F.C. and the R.N.A.S. into the R.A.F. on April 1, 1918. It is unclear why Mathews does not appear in Munsell’s “Air Service History.” Similarly, the “Roster of Second Detachment” does not record any squadron assignments for him; the “Roster from Clayton Knight” confuses him with Alexander Ferdinand Mathews. I find no casualty form for Mathews, although it is possible that some information (date of assignment to No. 218 Squadron) on the form for H[enry] W[illiam] Matthews (of whom more below) has inadvertently been taken from Mathews’s record. See “2nd Lieut. H W Matthews RAF.”

20 See 218 Squadron R.A.F. Record book: 01 October 1918 – 31 January 1919, passim.

21 On the 17th and escort work, see Clapp, A History of the 17th Aero Squadron, pp. 25–26 and 55; on the 148th and escort or protection missions, see Taylor, A History of the 148th Aero Squadron, p. 27.

22 See Rossano, Stalking the U-Boat, Chapter 11, and Amerman, “Integration of US Marine Corps Aviation with the Royal Air Force in First World War,” Chapter 3.

23 Hayward, “Squadron History.”

24 Ibid.

25 Ibid.

26 Fréthun is occasionally referred to as “Fretnum,” possibly the result of faulty optical character reading of printed texts. Hayward, in his brief history of No. 218, states that the move was prompted by the enemy night raids on Dunkirk and the adjacent aerodromes. However, other squadrons (e.g., Nos. 202 and 211 R.A.F. and U.S. 17th and 148th Aero) remained despite the raids, suggesting that the raids may not have been the primary motive for the move.

27 See 218 Squadron R.A.F. Record book for October 2, 1918, morning food dropping mission.

28 218 Squadron R.A.F. Casualty reports and returns: 01 June 1918 – 31 January 1919. I am grateful to Andrew Pentland for this information. Sturtivant and Page, The D.H.4 / D.H.9 File, perhaps unaware that there were two men named Mathews/Matthews at 218 at this time, give the name of the pilot of D3099 in this incident as “HW Matthews.”

29 See 218 Squadron R.A.F. Flying times and record of officers services. Note: this appears to be a one-page summary with entries running from July 1 through October 4, 1918. It is possible that another page, to which I do not currently have access, has further entries.

30 H. A. Jones, The War in the Air, vol. 6, p. 395.

31 “The Great Varssenaere Raid – 13 August 1918,” where a copy of the R.A.F. 5th Group orders for the raid is quoted in extenso. See also H. A. Jones, The War in the Air, vol. 6, pp. 395–96.

32 H. A. Jones, The War in the Air, vol. 6, p. 531.

33 Ibid., p. 533.

34 218 Squadron R.A.F. Record book; 218 Squadron R.A.F. Bomb dropping and reconnaissance reports, and 218 Squadron R.A.F. Flying times and record of officers services. The bomb dropping report for this raid is difficult to read, hence the uncertainty about the map location reference. Subsequent information about Mathews’s participation in missions is based on these three sources. For digital images of World War I trench maps, including sheet 20, see the “WWI Trench Maps & Aerial Photographs” and/or “British First World War Trench Maps, 1915-1918.”

35 H. A. Jones, The War in the Air, vol. 6, p. 534.

36 Ibid., p. 535.

37 See copies in 218 Squadron R.A.F. Casualty reports and returns and 5 Group Files, 5 Group, R.F.C. and R.A.F. Casualty reports (my thanks to Andrew Pentland for these documents). In the latter the “7” has been crossed out and replaced with a pencilled “6” for the date. The page for October 6, 1918, in the squadron record book appears to be no longer to be extant; the one extant page for October 7, 1918, describes a raid along the coast, the weather being unfavorable for targeting the (unnamed) objective. The entry for D3099 in Pentland and Page’s The D.H.4 / D.H.9 File gives the day of the beach landing of D3904 as October 6, 1918, and the pilot as H. W. Matthews.

38 “Interesting Histories of Officers of Staff of Seventh A.I.C. and Instruction Department.”

39 War Department. Office of the Quartermaster General, Army Transport Service, Lists of Incoming Passengers, 1917 – 1938, Passenger list, convalescent detachment 182, S. S. Antigone; “William Mathews.”